Today, there are very few countries in the world that are “food independent”, or able to produce enough food to meet their domestic needs. While many communities around the world have historically practiced subsistence farming, agricultural policy and economic pressures have shifted emphasis from self-sufficiency to large-scale production for a global food system. With our food systems and supply chains growing in complexity each year, is the hope of us returning to a pre-industrial self sufficiency just a fallacy?

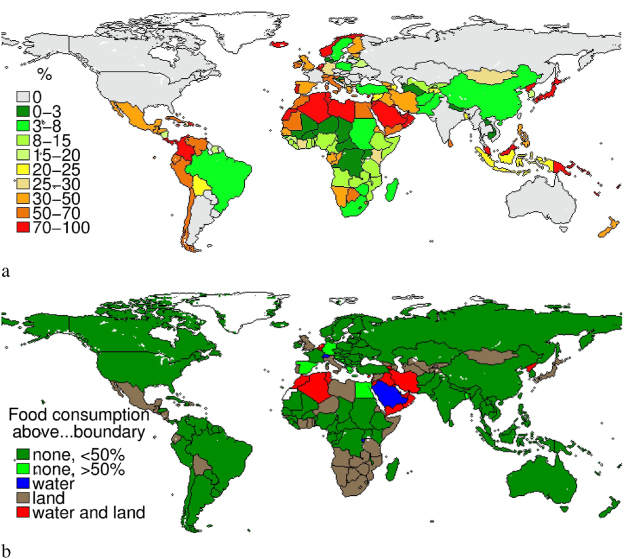

In a 2013 article for Environmental Research Letters titled “Spatial decoupling of agricultural production and consumption”, Marianela Fader et al. produced these maps to illustrate which countries were capable of self-sufficiency in terms of land and water for food production. The color-coded maps and accompanying article lay bare the dependence of 950 million people on external imports, and the 66 countries unable to be self-sufficient.

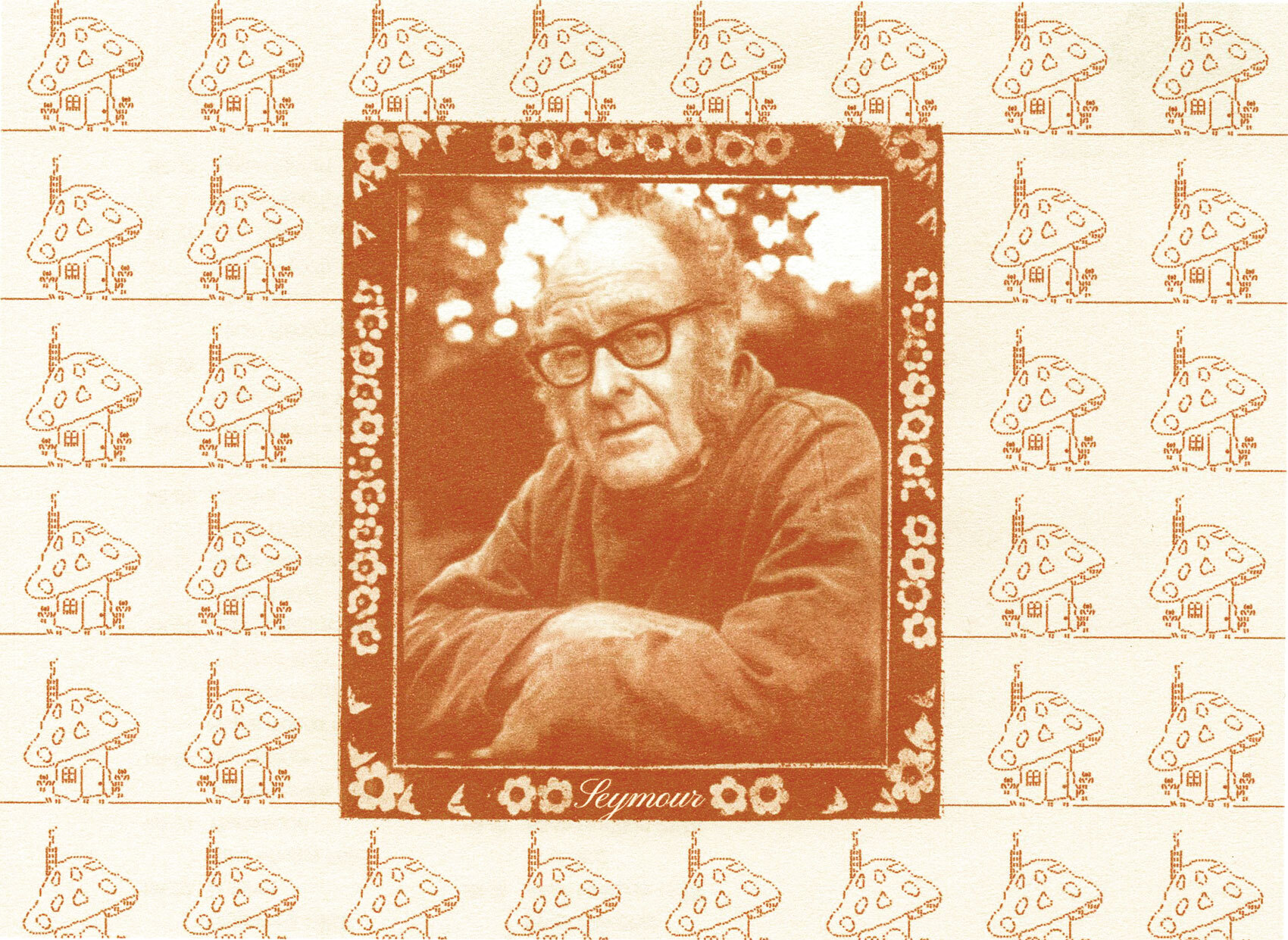

The dream of self-sufficiency is not a new one — a look back across recent history shows several so-called back-to-the-land movements, from the UK’s wartime “Dig for Victory” efforts, to America’s counterculture of the 1960s-70s. In fact, British author and ecological pioneer John Seymour (1914-2004) is known as the “founding father” of self-sufficiency in the UK, and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and its accompanying lockdowns brought increased interest in getting by without the help of others. Whether that be the convenience of supermarkets and imports, or simply the absence of friends and family. A surge in gardening during lockdown has resulted in huge waiting lists for allotments in the UK, with residents of East Lothian in Scotland facing a 16 year waiting list for their own veg patch. An estimated 700,000 people have left London to move to rural areas over lockdown.

These attitudes hearken back to the self-sufficiency movement of the 1970s — an era in which post-war struggles and the darkness of modern living drove many to move away from cities in pursuit of a “simpler life”. The 2015 Walker Art Center exhibition, Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, defines this movement as “refusing mainstream society in favor of ecological awareness, the democratization of tools and technologies, and a more communal survival.” The anti-capitalist, experimental counterculture of the ‘60s and ‘70s “reconditioned modernity” into something separate from the technological and built-up world.

“The counterculture was so successful in its moment because it actively ‘prototyped’ the future it wanted to live.”

– Andrew Blauvelt, curator and editor of Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia

Living off the fat of the land

So what exactly influenced these attitudes, and what does it mean for today’s ‘hippie modernists’ –– those leaving the smog of capital cities behind in search of a simple life, waiting years for a shared vegetable plot, or simply growing tomatoes on their windowsills? John Seymour was a British author, reporter and environmentalist, who adapted to a rural life with his family in the decades after World War II. Born in London, Seymour studied agriculture before travelling around Africa and Asia to gain experience in farmhand work, and learn indigenous practices.

After his travels, Seymour leased five acres of isolated land in Suffolk with his wife Sally, developing a lifestyle of self-sufficiency along the way. “We knew nothing at all about gardening but we bought a book on it,” Seymour writes in The Fat of the Land (1961). Living over a mile away from the closest neighbouring house, he recalls that initially “there was so much to do just to stay alive that we both simply moved about in a kind of daze”. The isolated nature of the Seymours’ dwelling meant it only felt sensible to start to produce their food themselves. Beginning with vegetables, then geese and ducks, chickens, a cow for milk and butter, and then pigs.

“We never had any real conscious drive to self-sufficiency.

John Seymour, The Fat of the Land, 1961

We had thought, like a lot of other people, that it would be nice to grow our own vegetables.”

This memoir, which also serves as an introduction to subsistence farming, is not just one man’s memories of transforming a home and garden — it is a rich and personal, often humorous, insight into the detachment we have suffered from our land, and our food, and how we can repair it. Seymour writes of the learning curve of growing fruit and vegetables in poor soil, rearing geese (“Later, we found that it was quite unnecessary to keep so many geese”) and milking a cow (“It is no use calling on the Lord God. He won’t come down and help you. You are alone –– with a cow”).

After writing The Fat of the Land and later moving to a farm in Pembrokeshire, Wales, John Seymour went on to write The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency, providing a guide for others looking to embrace a rural, less-processed lifestyle — sparking a movement of avid home-growers, landowners and foragers in the UK and beyond. The bestselling manifesto sold more than a million copies, and built the reputation of publishers Dorling and Kindersley, now known worldwide as publishing house DK.

The Good Life

The ‘back-to-the-land’ movement of post-war life was also seen in the USA, with Helen and Scott Nearing’s 1954 guide, Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World –– a book advocating for modern day “homesteading” and an organic, ascetic lifestyle, which the couple adopted during the Great Depression.

Back in Britain, the growing awareness of self-reliance and a connection with nature was becoming a lifestyle trend –– the BBC sitcom The Good Life ran for four seasons from 1975-1978. It tells the story of Tom Good, who gives up his job in a plastic toy factory and convinces his wife Barbara to turn their suburban London home into a self-sufficient farm. The show’s comedy comes from the couple’s clashes with their next door neighbours, the Leadbetters, who do not understand their lifestyle.

So are we going through another back-to-the-land movement? Are the behaviours we categorised as “lockdown habits” actually just the beginning of a transition back to nature? Perhaps the damning daily news of food inequality and shortages, and climate meltdown is nudging us to take matters into our own hands.

On social media, this idea is only reaffirmed. The revival of images and art that depict fields of flowers, wildlife and scenes that could only be reminiscent of Victorian pastoral life –– an aesthetic named “cottagecore” –– suggest younger generations are being drawn to the countryside. Aesthetics Wiki defines cottagecore as a “romanticization of the English countryside”, and pins its latest resurgence on the COVID-19 pandemic.

The social media account of Mother the Mountain Farm documents the care of a regenerative farm on the east coast of Australia, by sisters Julia and Anastasia Vanderbyl. The farm’s Instagram presence has gained 266,000 followers due to their idyllic, sun-soaked work setting, and (adorable) documentation of their relationships with the farm’s animals. Other accounts, such as @cottagecoredream repost other users’ content to create a moodboard of “slow living” scenes.

Although this comeback of the self-sufficient lifestyle is certainly reminiscent of Seymour’s manifesto and the counterculture of the late 20th century, are we contradicting its very cause by engaging with it as a trend, an aspiration that becomes a marketing tactic? Or have we more chance of a wide-spread and lasting movement back to nature now, thanks to the abilities of social media to share information?

There is no doubt that the relaxing activities we engaged in when faced with the pandemic; gardening, baking bread, fermenting — have helped us take the first steps to rekindle our relationship with our food and nature. From examples that have come before, returning to the land is often a result of a dissatisfaction with urban life or societal problems. Those who leave the city or town behind are searching for a better life — without much understanding of how this life will work. There is more to be done if we want to truly reconnect with the land, beyond double-tapping on Instagram or watering a singular tomato plant — but perhaps it’s a good start.