Last fall, a 30-meter-long living artwork was presented outside government buildings in London – “We the 174,183 demand allotments”. These numbers were collected by JC Niala with fellow artists Julia Utreras and Sam Skinner for The Waiting List, a project supported by Greenpeace.

In a different activation, the artists used waiting list data gathered from all 378 councils in Great Britain, to create a vast (allotment-sized) piece of seed paper to illustrate the demand for land. The artwork was presented at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (the government department responsible for local councils), before being guerrilla-planted in a vacant lot owned by supermarket giant Tesco in Liverpool. The seeds for the artwork were selected due to their ability to reduce contaminants, and build organic matter in the soil – creating, by its very nature, a space suitable for future growing.

JC Niala“Allotments have always been about more than growing food.”1

- 1. Niala, JC. ‘A 1918 Allotment in 2021’, Fig, May 2021.

The word allotment originates from sections of land being ‘alloted to an individual’. 2 Cities, towns and suburbs in the UK are peppered with allotment sites, recognisable by the crooked skylines of bamboo structures, fruit trees and pop-up greenhouses. Similar to community garden models found elsewhere in the world, the UK’s allotment system allows residents looking to grow their own food the opportunity to rent a plot to do so.

Allotments have always felt permanently stamped on British landscapes, but a study by University of Sheffield in 2020 found that “space for urban allotments fell by 65 percent from 1960 to 2016”. The study also found that the land lost held the potential to grow “an average of 2,500 tonnes of food per year in each city,” with more economically deprived areas seeing the largest cuts in space. 3

Worryingly, this loss of land is contradicted by increased civilian demand and growing waiting lists across the UK for plots, as it is clear more people want to grow their own food, connect with their communities or simply spend time outdoors. But why now, and how did this model of land use begin?

- 2. “History and legislation: Origins of allotments” (1998), Environment, Transport and Regional Affairs Committee, House of Commons.

3. “Allotment land cut by 65 per cent since mid-1900s” (2020) The University of Sheffield.

Stealing the common from the goose

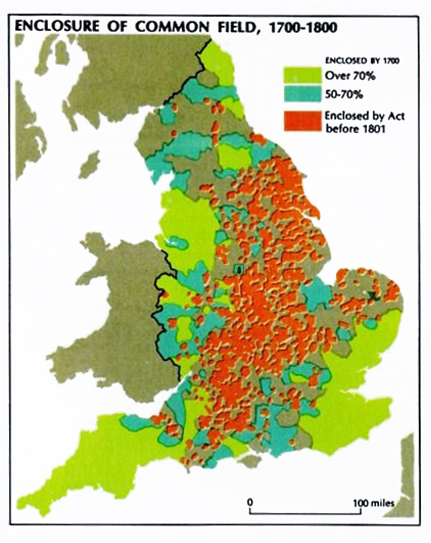

The introduction of allotments in the United Kingdom derives from the Inclosure Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries, which literally ‘enclosed’ and thus greatly reduced access to previously common land across the country, with the aim of improving agricultural productivity.

- 4. Boyle, J. (2003). “The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the Public Domain” Law and Contemporary Problems, 66(1/2), 33–74.

“The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater felon loose

– Extract from an anonymous poem protesting the enclosure legislation, 18th century4Who steals the common from the goose.”

The displacement and limited access to land caused by these Acts eventually resulted in the first allotment legislation, requiring local councils to provide a “sufficient number of allotments” to respond to demand from residents.5

Self-sufficiency during uncertainty

But this is only the beginning of the demand for allotments. Both the First and Second World Wars saw the adoption of public spaces for growing – for wellbeing, for connection to others, and for survival. The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) of 1914 gave local authorities in the UK the power to take over land for the war effort, including for allotment plots to combat food shortages.6 This was followed by the famous Dig for Victory campaign during WWII, which encouraged the public to grow food in their gardens and public spaces to combat food shortages as well as boost morale. “Victory gardens” took root world over, from the US to Australia.

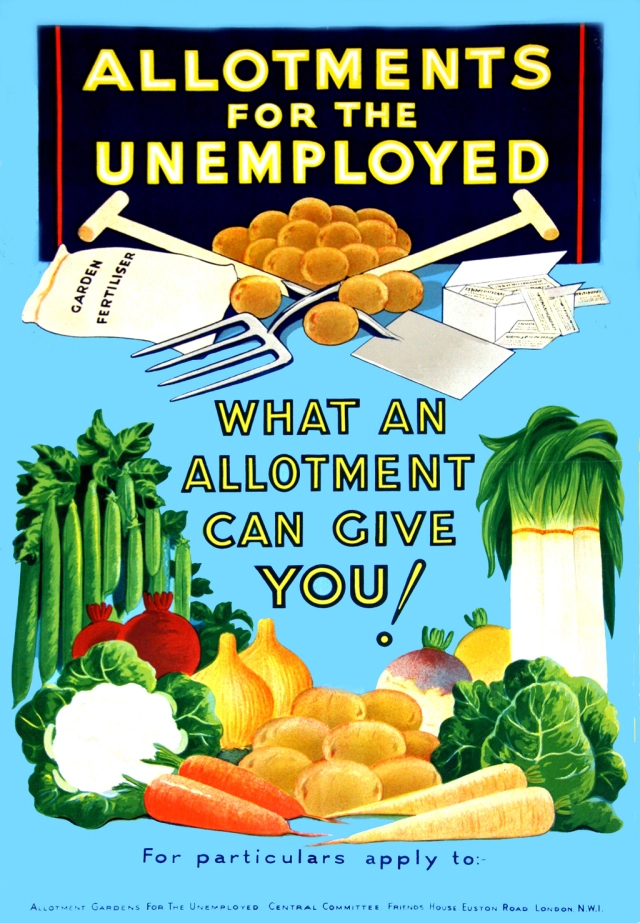

It wasn’t only conflict that spiked interest in growing spaces – the Great Depression brought mass unemployment to the UK during the 1920s-30s, and an Allotments for the Unemployed initiative, which provided those struggling to find work with allotment sites, materials and tools, began in Wales before quickly spreading to England.7

- 6. “The development of allotments during the First World War”, Clements Hall Local History Group.

7. Wall, J. “A brief history of the allotment movement in Britain based on Growing Space by Lesley Acton”, The Moseley Society.

A parliamentary debate on the allotments scheme in 1931 highlights the impact of providing these plots on food security:

Mr. Wise, Allotments (Unemployed Workers), Volume 256: debated on Tuesday 22 September 1931“It has been calculated that the 64,000 unemployed men who last year were enabled to cultivate allotments under the arrangements made probably added about £500,000 worth of foodstuffs to the available supply, which, if they had not been produced here, would clearly have had to be imported.”8

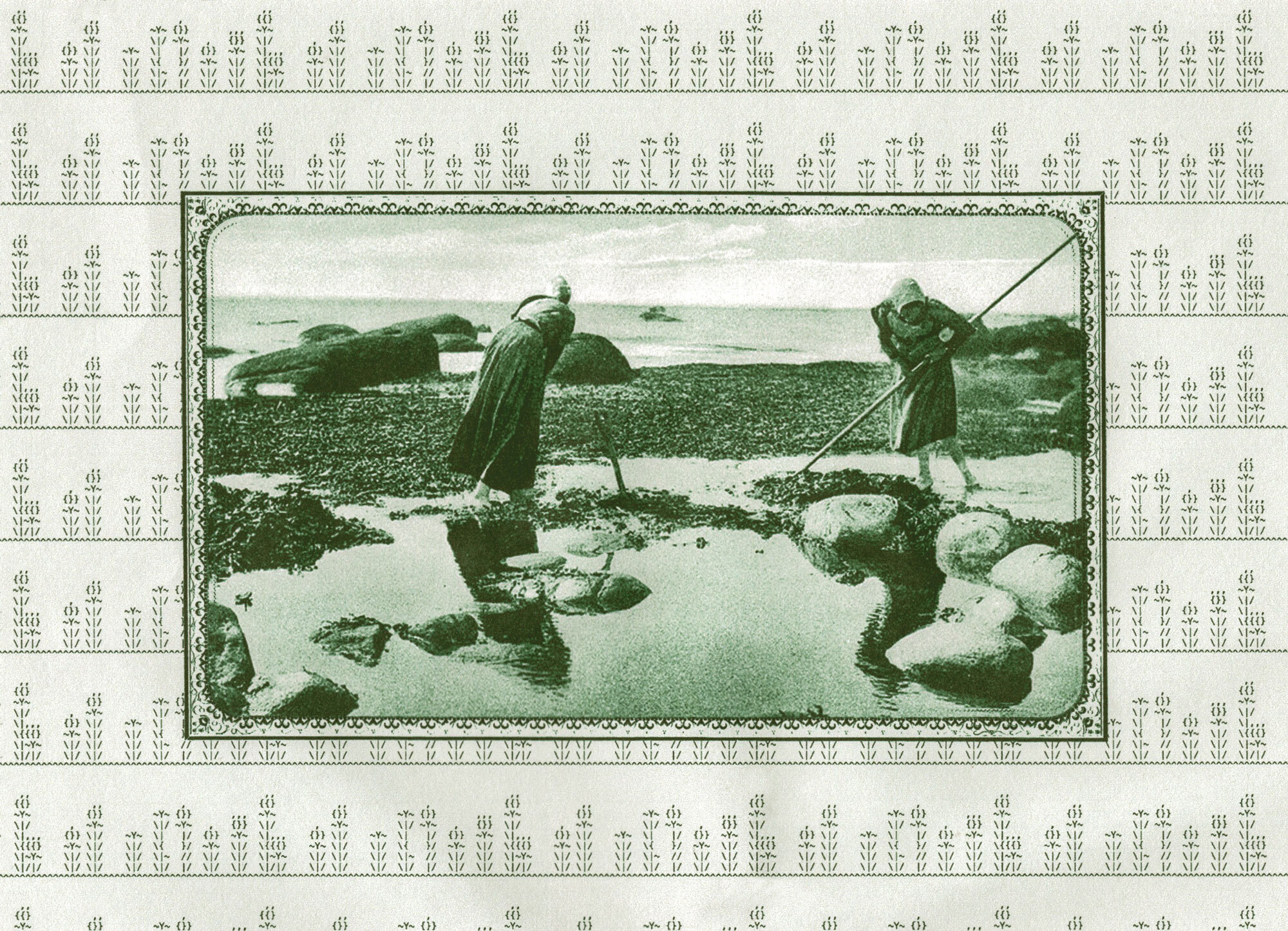

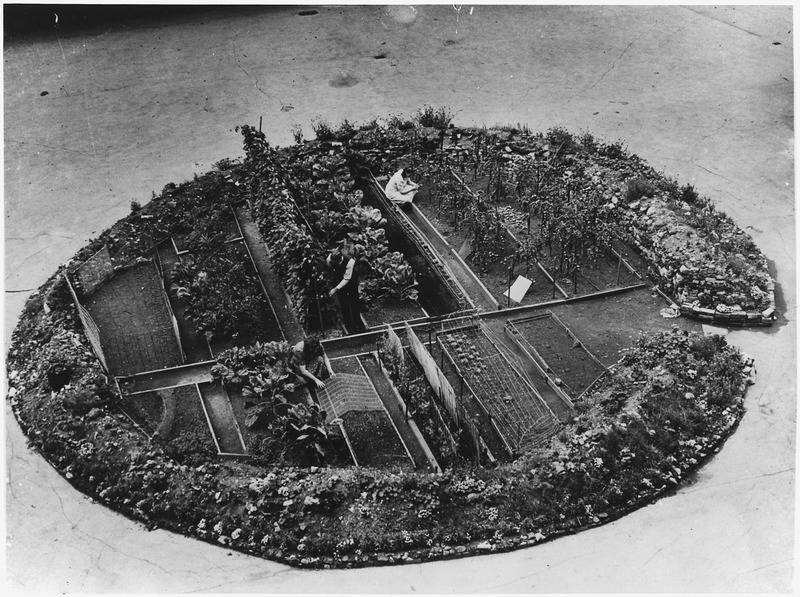

In the 2021 project 1918 Allotment, historian and artist JC Niala explored the relationship between the First World War, the 1918 flu pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic through the role of allotments. Taking over an Oxford allotment plot, Niala recreated a 1918-style allotment, growing open-pollinated, heirloom plant varieties from the era, to bring both health crises – past and present – into conversation and examine the power of these growing spaces in public health, food security, and community.9

When speaking to JC Niala, whose doctoral research explores the historical significance of allotments during times of crisis, she summarised that an explanation for the demand for allotments is simple – our response to a crisis is so often to connect to the land.

- 9. “1918 Allotment,” Fig Studio.

Back to the land

Interest in allotments dipped in the post-war years as we were won over by shiny, new, fast living, and land previously used for food growing was taken over for building development. As we moved forwards and recovered from crisis, allotments possibly felt like a reminder of the past, and of difficult times that we’d rather forget. Despite a brief resurgence due to the 1974 economic crisis, by the latter half of the decade numbers of plots had continued to decline.10

But the COVID-19 pandemic saw an uptick in allotment usage once more, as lockdowns gave many the time to learn new skills, spend time outdoors and prioritise recreational activities.11 History repeated itself as people turned to growing to combat food shortages and improve their health and wellbeing (with lockdowns and the resulting isolation particularly affecting mental health). Research published during the pandemic suggests allotments provide “a spectrum of benefits for the individual, such as community cohesion, mental health and nature connectedness”.12 But amidst increased demand and reported social benefits, the waiting list for allotments has almost doubled in 12 years – showing that adequate land is not being provided for those awaiting a plot.13

Our history and relationship with allotments shows them as a tool for navigating crisis, a space for exchanging knowledge and resources, a chance to repair and reconnect with the land – and this hasn’t changed. The peaks in allotment use correlate with spikes in national uncertainty, as we grapple for ways to respond, heal and survive. But what if allotments could be here to stay? What if land was put back into the hands of communities, and growing became commonplace?

- 10. Acton, L., (2011) “Allotment Gardens: A Reflection of History, Heritage, Community and Self”, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 21, 46-58. doi: https://doi.org/10.5334/pia.379

11. Smithers, R. “Interest in allotments soars in England during coronavirus pandemic” (2020) The Guardian.

12. Dobson, M.C. et al. (2021) ‘“My little piece of the planet”: The multiplicity of well-being benefits from allotment gardening’, British Food Journal, 123(3), pp. 1012–1023. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-07-2020-0593

13. Gayle, D. (2023) “Waiting list for allotments in England almost doubles in 12 years”, The Guardian.

- 1. Niala, JC. ‘A 1918 Allotment in 2021’, Fig, May 2021.

- 2. “History and legislation: Origins of allotments” (1998), Environment, Transport and Regional Affairs Committee, House of Commons.

3. “Allotment land cut by 65 per cent since mid-1900s” (2020) The University of Sheffield.

- 4. Boyle, J. (2003). “The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the Public Domain” Law and Contemporary Problems, 66(1/2), 33–74.

- 6. “The development of allotments during the First World War”, Clements Hall Local History Group.

7. Wall, J. “A brief history of the allotment movement in Britain based on Growing Space by Lesley Acton”, The Moseley Society.

- 9. “1918 Allotment,” Fig Studio.

- 10. Acton, L., (2011) “Allotment Gardens: A Reflection of History, Heritage, Community and Self”, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 21, 46-58. doi: https://doi.org/10.5334/pia.379

11. Smithers, R. “Interest in allotments soars in England during coronavirus pandemic” (2020) The Guardian.

12. Dobson, M.C. et al. (2021) ‘“My little piece of the planet”: The multiplicity of well-being benefits from allotment gardening’, British Food Journal, 123(3), pp. 1012–1023. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-07-2020-0593

13. Gayle, D. (2023) “Waiting list for allotments in England almost doubles in 12 years”, The Guardian.