Repast tells the stories of people, places and foodways throughout history, and how they can help us design better food futures.

Although cereals were some of the earliest crops to be cultivated by humans, what we now know today as ‘breakfast’ cereals are a relatively recent invention.

Originating in North America, manufactured breakfast cereals were born from the idea that one should start their day with a bowl of something that was (let’s face it) bland, fibre-rich and “good” for us. Today the cereal aisle has evolved to encompass a wide variety of ready-to-eat foods, from sugary snacks with cartoon ambassadors to cereal bars for the on-the-go breakfaster. Across this evolution is a bizarre history, one of religious guilt, a quest for health, and in some cases, mind control.

The Cereal and the Sanatorium

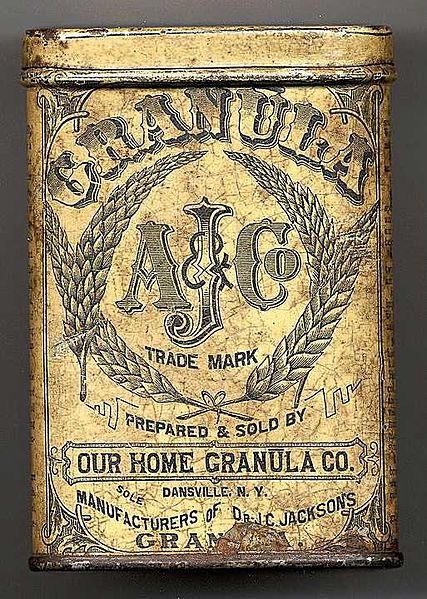

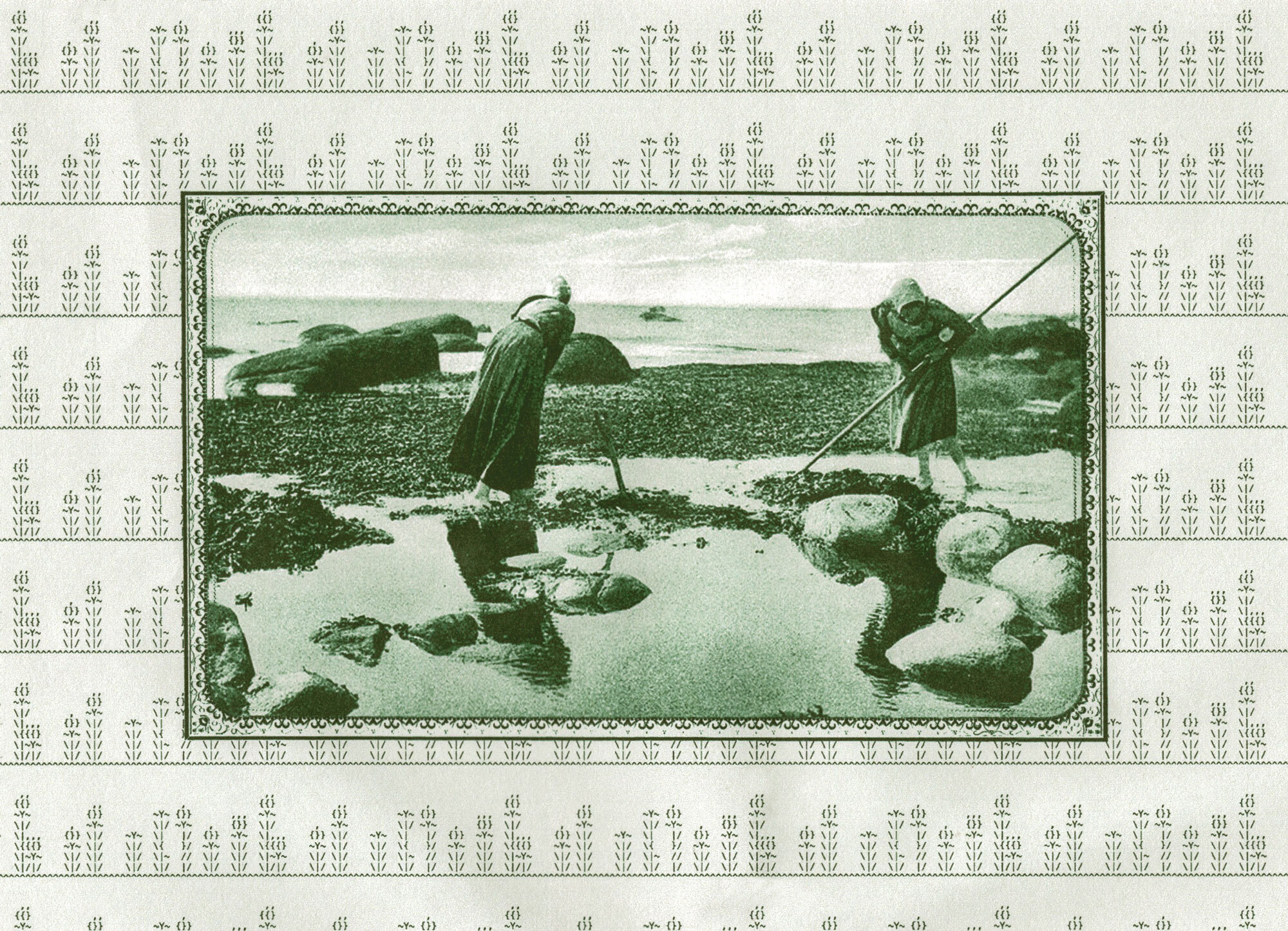

The story begins in 1863 when James Caleb Jackson invented the first breakfast cereal, “granula”. Made primarily from graham flour, granula was so hard and inedible that it had to be soaked overnight in milk to be remotely appetising (and so began the totally normalised behaviour of dowsing our breakfast in milk).

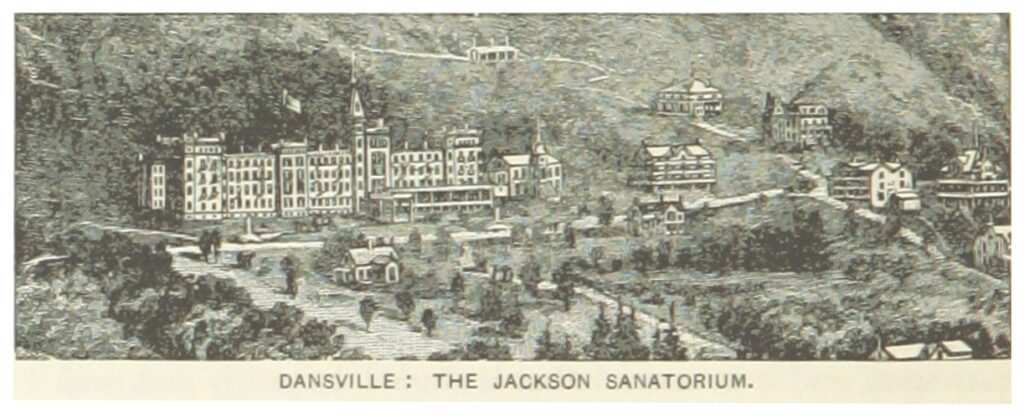

An advocate for “the water cure”, or hydropathy1, Jackson ran a spa named Our Home on the Hillside, in Livingston County, New York. Over time its popularity led to the spa becoming known as The Jackson Sanatorium. However, it wasn’t just water that Jackson believed could cure our ailments. He also was a strong advocate for healthy eating and promoted an unprocessed vegetarian diet within the spa. A member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Jackson believed that this wholesome diet – including granula – could rid the mind and body of evils, including curbing sexual desire and masturbation.

An article for climate justice platform Grist (2008) suggests the 19th century American diet of meat, booze and coffee resulted in the Adventists’ somewhat revolutionary dietary guidelines – “To rid America of these vices, religious zealots spearheaded the country’s first vegetarian movement.”

- 1. “Hydropathy as a formal therapeutic system came into vogue during the 19th century through the efforts of Vinzenz Priessnitz (1799–1851), a Silesian farmer who believed in the medicinal value of water from the wells on his land.” Encyclopedia Britannica

A Quest for Sinless Sustenance

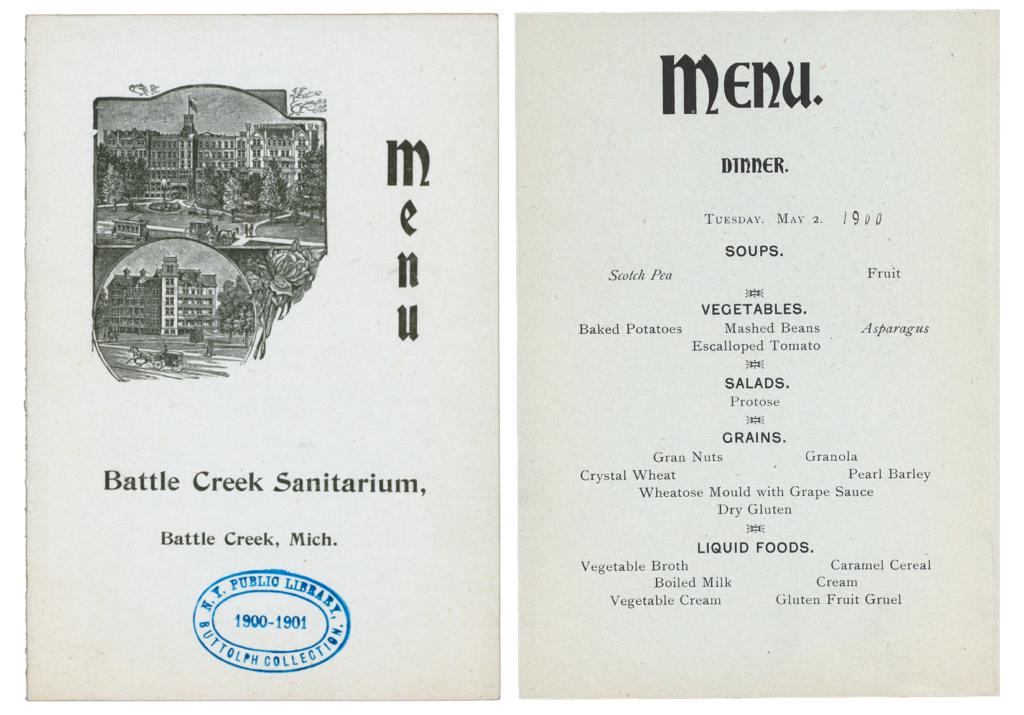

A few years later, John Harvey Kellogg – coincidentally also a Seventh-day Adventist and chief medical officer of Battle Creek Sanitarium, Michigan – created his own version of granula. However, when Jackson threatened to sue him, Kellog renamed his version to “granola”. The Kellogg family went on to introduce Corn Flakes in the 1890s, incorporating the cereal into patients’ diets at the sanitarium. Considered an anaphrodisiac, it was hoped that a bland diet would quell any sexual arousal. A menu from the Sanitarium dated 1900 (pictured below) displays the uninspiring food choices on offer – from ‘Protose’ (a meat substitute made mainly from wheat gluten and peanuts – a Kellogg invention, of course) to Granola or ‘Dry Gluten’.

Granola and Corn Flakes were just the beginning of Kellogg’s quest to develop a multitude of cereal products that would reinforce his beliefs and those of the Church to which he belonged. Food scientist Abbey Thiel writes that, “due to his religious beliefs that flavorful foods were sinful and unclean, Kellogg was forced to think creatively and innovate when preparing meals.” (Heated, 2019)

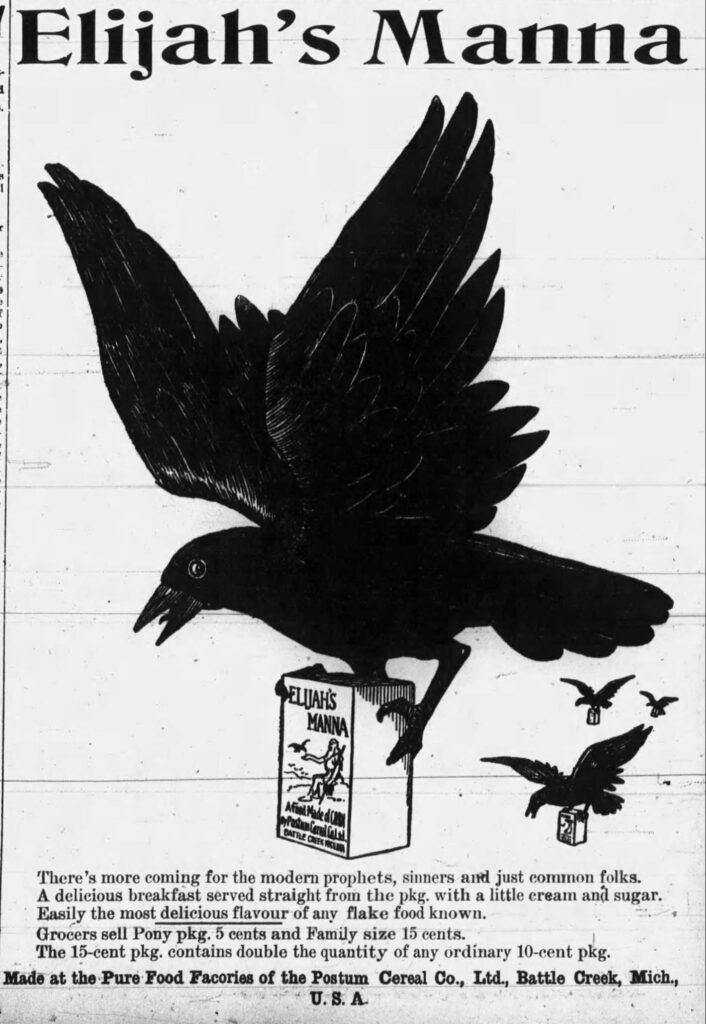

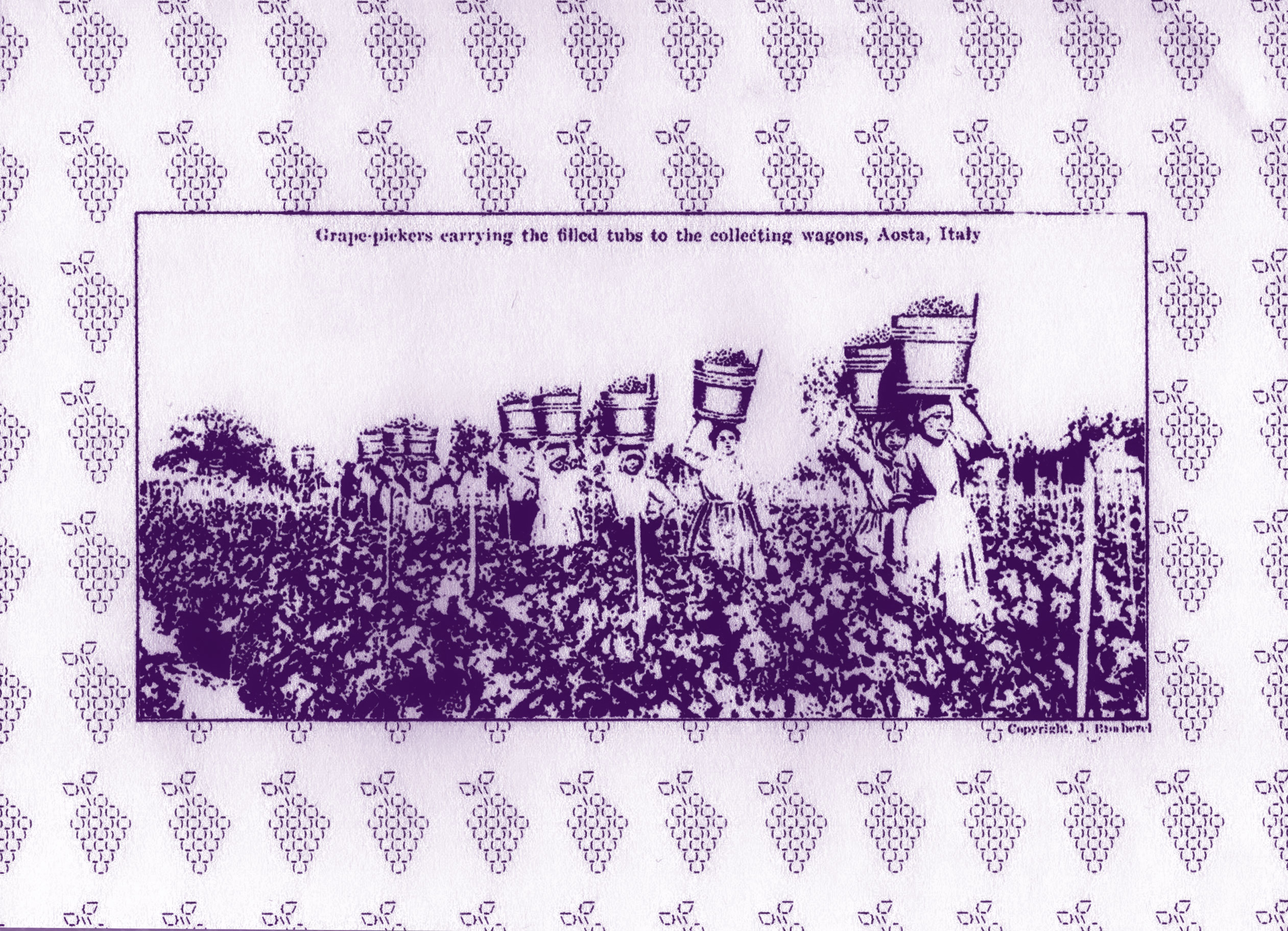

Elijah’s Manna

Although Seventh-day Adventists developed the first manufactured cereals, it was the Quaker Oats company that made history registering the first trademark for a breakfast cereal in 1877. A recognisable Quaker character remains on the products’ packaging today, representing the faith’s values of purity, strength and honesty. While we now know that it is no coincidence that the founders of the original breakfast cereals used Christian beliefs and food guilt to sell their cereals – at the time religious imagery proliferated across the industry and its marketing. A former patient of Kellogg’s, C.W. Post created his own first cereal, Grape-Nuts in 1897. Inspired by the emerging cereal revolution, he attempted his own version of corn flakes called ‘Elijah’s Manna’ (Elijah referring to the Biblical prophet, and manna, a wafer-like food that God provided for the Israelites). A 1907 newspaper advert introduces the product with the line, “There’s more coming for the modern prophets, sinners and just common folks.” The resulting backlash from religious groups and slow sales forced Post to change the cereal’s name to the inoffensive ‘Post Toasties’ – now discontinued.

Although the cereals of the early 1900s were, for the most part, of the same bland flavour palate (a side of effect of manufacturers essentially copying one another), most cereal adverts of the time also included a line around each cereal’s flavour or nutrition being inimitable. In The Battle Creek Sanitarium System: History, Organization, Methods (1908), J.H. Kellogg himself writes “The Battle Creek Sanitarium has no connection whatever with these questionable exploitations. The first thoroughly cooked and dextrinized cereal food preparation was a Battle Creek Sanitarium product.” – with no acknowledgement of John Caleb Jackson’s previous invention.

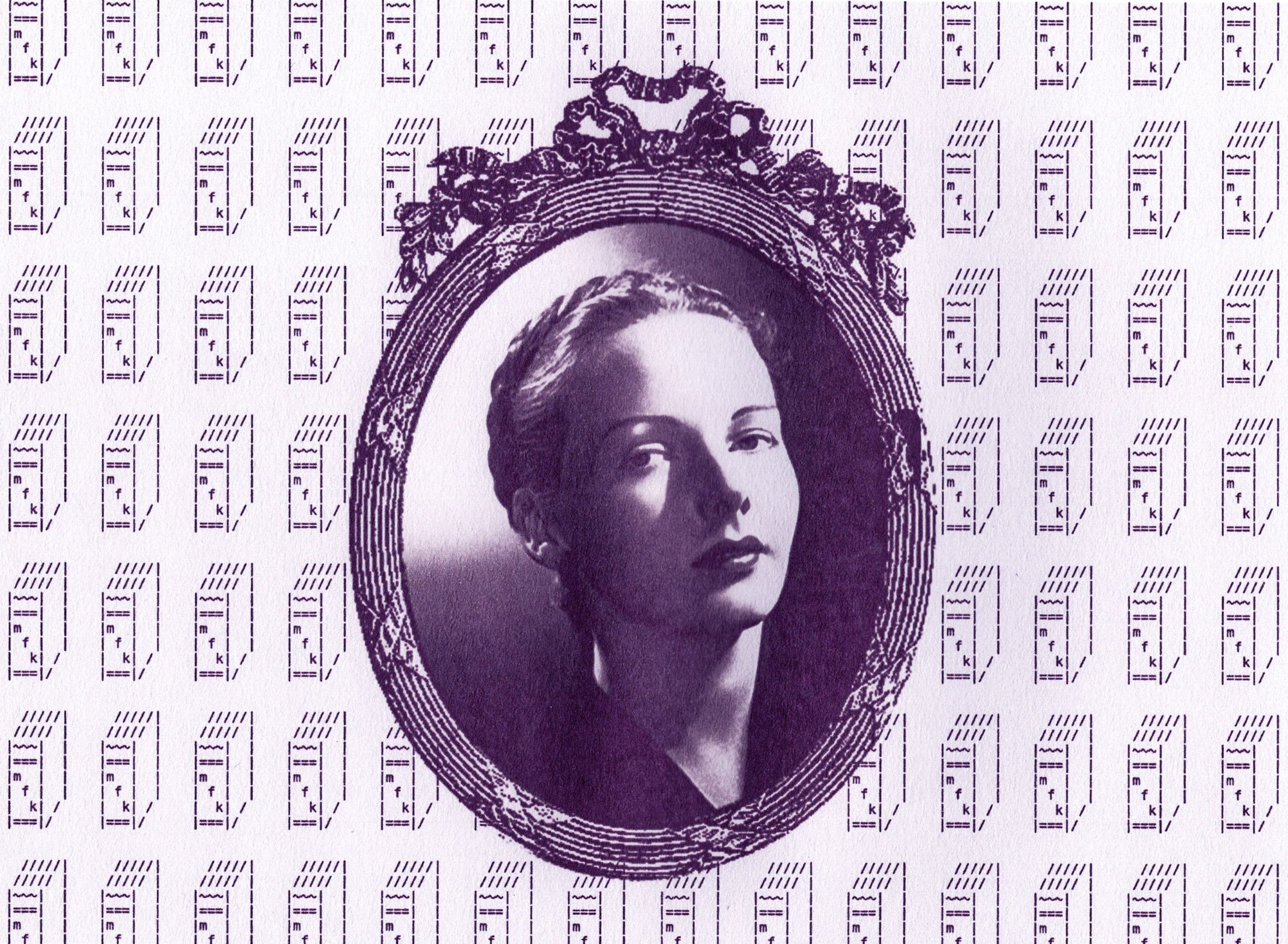

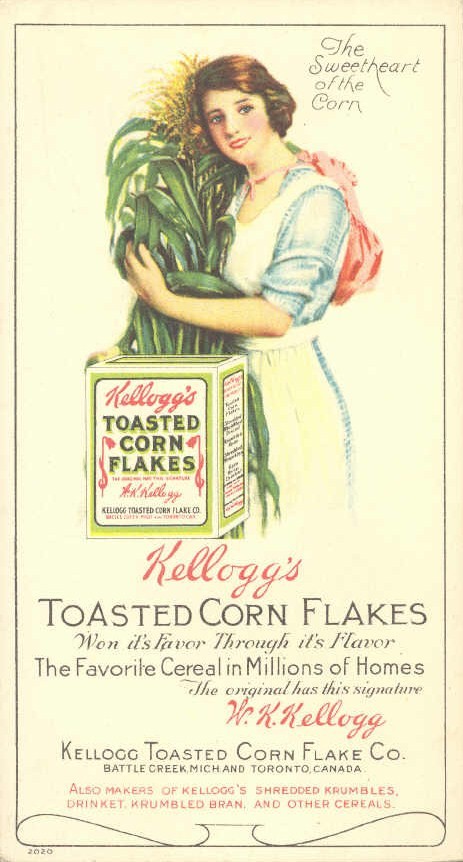

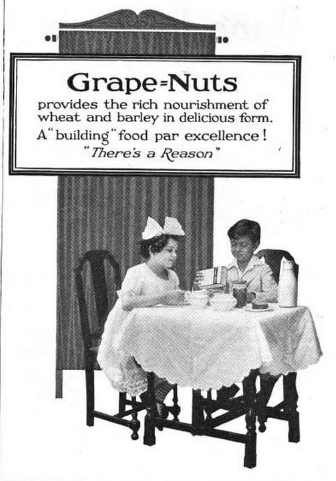

Children and women were also used as marketing strategies to emphasize the moral underpinnings of the products. This 1910 Corn Flakes advertisement (below) uses imagery of feminine beauty and purity to market breakfast cereal. A 1919 Grape-Nuts advertisement depicts a childhood innocence and promotes the “nourishment” of Post’s invention, with the brand’s somewhat ominous tagline, There’s a Reason.

Mind Control and Market Changes

Although the commercial breakfast cereal industry had its roots in Protestant Christianity, it wasn’t long before it was adapted to suit other agendas and markets. For example, by the 1930s, Purina Mills (originally producing animal feed) had joined forces with Webster Edgerley, founder of a racist social movement called Ralstonism. The newly named Ralston Purina introduced a dry cereal called ‘Shredded Ralston’, which Edgerley hoped would prove popular among his followers. The aims of Ralstonism included forming a “new race” by following Edgerley’s pseudoscientific advice on diet, exercise and general lifestyle choices, like walking on the balls of one’s feet and avoiding walking in straight lines. The wholewheat cereal promoted by Ralston Purina was part of the dietary guidelines of Ralstonism, which if adhered to carefully, promised followers the power of mind control and telepathy. Luckily, Ralstonism did not take over America, although the company has since been purchased several times.

While the early iterations of breakfast cereal had intended to improve the health and “purity” of adults suffering from all manner of physical and spiritual ills, post World War II, cereal’s target audience shifted from the maladied to baby boomers. Sugar became a selling point and family-friendly cereals were the next big thing. Kellogg’s reinvented their corn flakes, creating Frosted Flakes (1952) by simply adding a coating of sugar and an anthropomorphic mascot to their best-selling cereal. In 1966, Quaker Oats introduced their instant oatmeal, with their first sickly sweet flavour — Maple & Brown Sugar — arriving in 1970.

It seems almost comical that the initial call for breakfast cereal — an ascetic attempt to relieve the American citizen of toxicities and evil temptations — has now become a sugar-laden treat complete with a plastic toy hidden at the bottom as a ‘prize’. As the target market and aims of cereal have changed, so have the nutritional content, flavour, advertisements and packaging of the popular breakfast food. DIY archival projects such as this collection of cereal box backs that feature comic strips, Disney characters and games bear little resemblance to the health-concerned inventions of the 19th century. Wholegrain, wholewheat and fibre-rich cereals for adults still exist and likely always will, but the excitement for their digestive benefits has been lost amidst generations of food fads and our ever-evolving attitudes towards health and wellness.