For many of us, the ritual spreading of butter is so quotidian, it is barely considered a culinary practice. In Western grocery stores, butter can be found in plastic tubs or foil packets, its unremarkable presentation mirrored in the artless manner in which we use it. However, there are signs that we are re-learning how to appreciate this everyday ingredient, its historical significance as well as its future possibilities. One example is the return of butter sculpting, a centuries-old practice, to our dining tables. Over the past few years, social media has been awash with artists, food stylists and cooks using the medium of butter to create three-dimensional centerpieces reminiscent of those found in medieval banquets. The transformation of unassuming ingredients into sculptural art forms invites diners to change the way they approach their food, encouraging them to spend longer engaging with it, and places more value on the eating experience than it would if presented with a small square of butter in a foil wrapper. Although present in banquet halls since the Renaissance period, butter sculpture as a visual art only came to prominence in the 19th century, thanks to farmwoman-turned-sculptor Caroline Shawk Brooks.

Rural women’s work

In 19th-century America, women’s work on farmland was integral to the success of the business – although it wasn’t celebrated as such. Farmwomen typically took on the work of raising and processing crops and animal products from the land, in particular eggs and dairy. So-called “butter-and-egg money” was often the only income a farmer’s wife could claim as her own. It wasn’t uncommon for butter molds to be used to shape and stamp decorative and recognisable designs, enabling consumers to easily select their favorite butter.

Caroline Shawk Brooks, born in 1840, spent her days in Helena, Arkansas working on the farm she shared with her husband. However, in 1867, she created her first butter sculpture. Without the use of a mold, she sculpted a shell using the tools readily available in her home. This marked the beginning of an artistic practice that would soon have her known as “the butter woman”. Brooks once stated that her first butter sculpture was made “the year the cotton crop failed”. Aiming to supplement the farm’s income, Brooks continued to sculpt various works in butter for family and friends, forming the likeness of animals and even human faces.

A study in butter

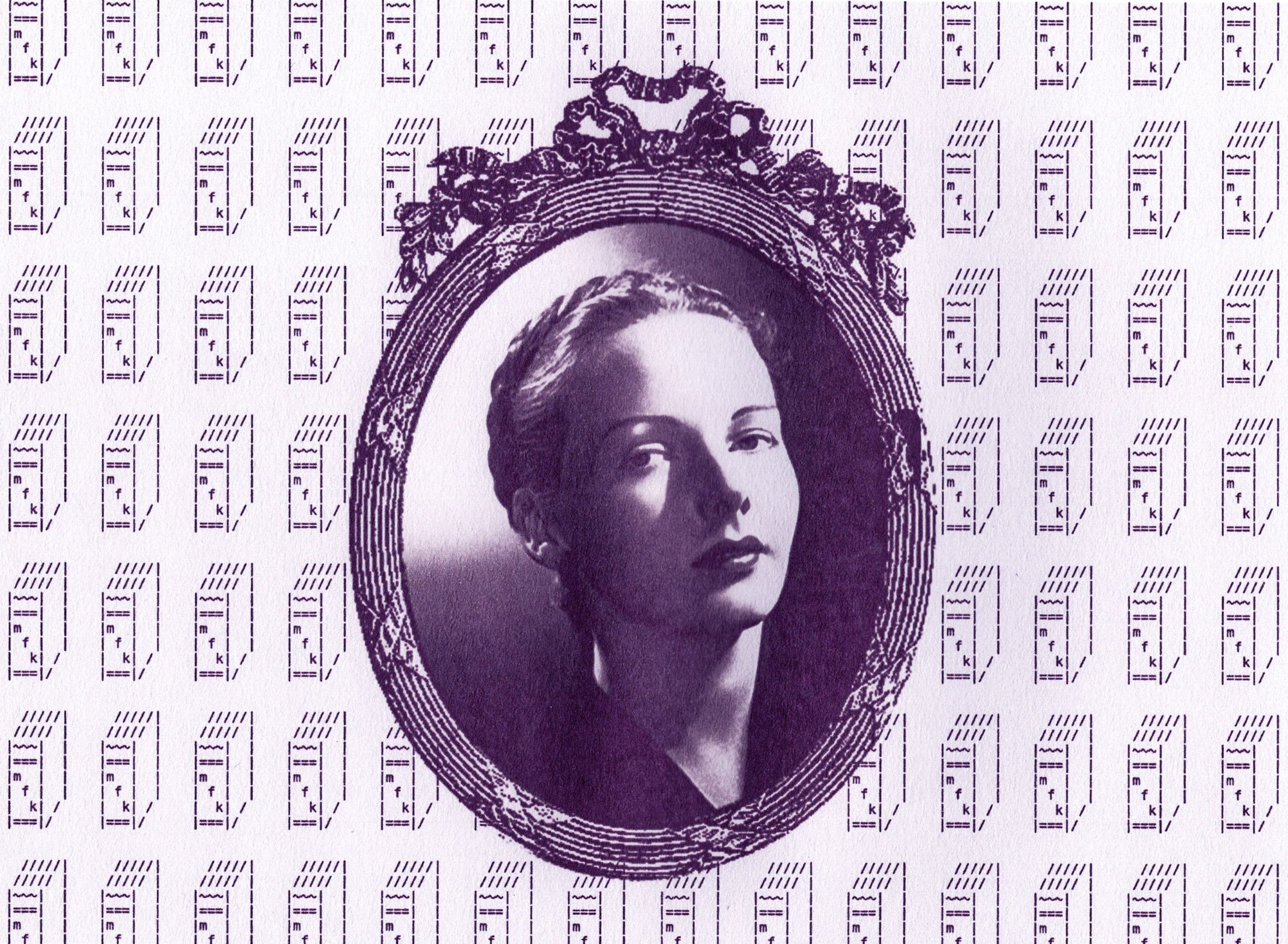

It was after reading the Danish verse drama King Rene’s Daughter by Henrik Herze that Brooks was inspired to create the sculpture that would thrust her from a world of routine farm chores to international exhibitions. The play tells the fictional story of a teenage princess, Iolanthe, who lives in seclusion in a hidden garden, kept unaware of her own blindness by her family. She is tended to by a doctor who puts her into an enchanted sleep daily, and predicts that she will regain her sight at the age of 16, when she is also due to marry. Moved by the story, Brooks chose to sculpt the sleeping princess in her “last moment of innocence” before she is cured and begins a new life.

There could be significance in Brooks’ choice to sculpt this character—which she replicated several times over the years—a young woman whose path in life had been decided for her, the outside world just beyond reach. At this time, there was “certain work deemed proper to the farm wife”, however, like Brooks, women were aspiring to explore further disciplines, such as art.

In The New Century for Woman (1876), the newspaper for the Centennial Exposition’s Women’s Pavilion where a later model of Brooks’ Dreaming Iolanthe was exhibited, the sculpture is described in poetic detail, whilst the artist herself is identified as “untaught, untrained”. Despite not receiving formal artistic education, one could argue that spending day-in, day-out working with one medium and learning its qualities, restrictions and capabilities should make someone qualified in their craft. The article ends with a “hope for a bright and successful future for this Ohio girl.”

Common tools for an uncommon purpose

While exhibiting Iolanthe at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, Brooks was invited to demonstrate her butter sculpting in front of spectators. Although this could be perceived to be a great honor, it implied a challenge, to see if she was really the artist behind her work and could create a sculpture from scratch.

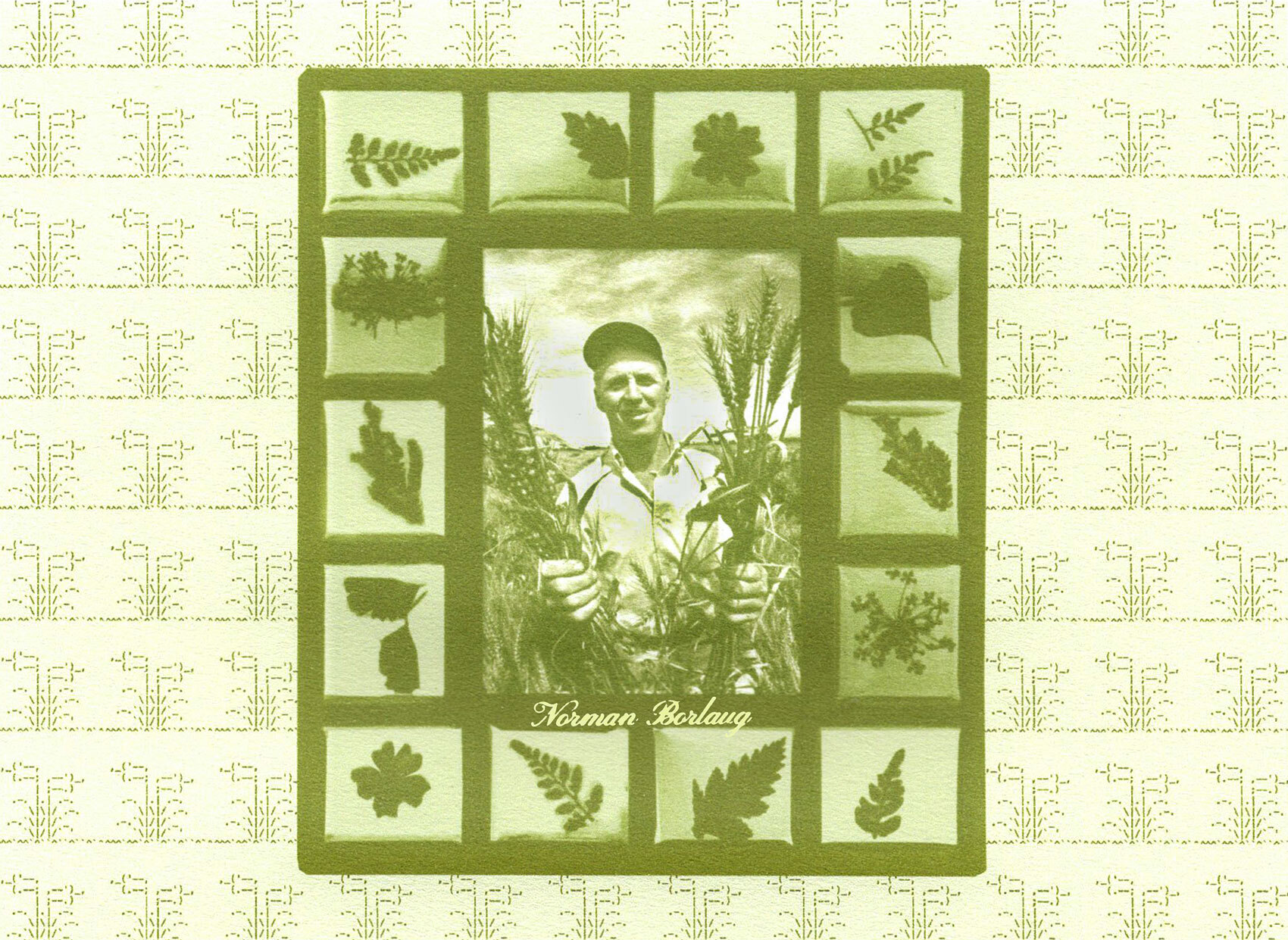

Using the traditional tools of a butter maker rather than those of a sculptor, Brooks was able to prove her understanding of the unique material. She worked on and preserved her sculptures by setting them in a metal pan filled with ice. According to the carte de visite produced for visitors to purchase from the exposition (pictured), she transformed the butter using a “common butter paddle, cedar sticks, broom straws and camel’s hair pencil” – treating the butter just as it was, appreciating its sensitivities, rather than forcing it to behave as though it were another medium.

Although Brooks’ process and skill was admired, it wasn’t exactly regarded as a form of fine art, nor she as a legitimate artist. Reports of the Centennial and other exhibitions of Brooks’ work focused on her domestic background and rural roots, her father and husband, her lack of training and her everyday tools – a pat on the back for being a woman and giving it a go. However, just a couple of years later after further exhibitions of her work it seems that Brooks had separated from her husband, and had opened a studio in Washington D.C. which she sculpted from.

“When I do portrait work, I work until I suit those for whom I am working. When I work for myself I work until I suit myself.” – Caroline Shawk Brooks

Brooks’ career continued into the late 1800s, when she continued to travel to New York, Florence and Chicago, sculpting portraits of politicians (including several U.S. presidents), writers and fictional characters. Although Brooks “struggled to make a living” from sculpting, she took a role that she had been restricted by and used it to pursue a craft, molding a new life from the very work that had previously restricted her to the home. As art historian Pamela Simpson writes in her account of the sculptor’s life and work, “she was successful, at least in part, because butter was a material associated with women.” It was because dairy was considered appropriate as women’s work that Brooks was able to shape a new life for herself. At the time, women had few rights or freedom. However it was through the avenue of farmwork that Brooks was able to gain access to her unique medium, which would later lead to her being hailed as “The Centennial Butter Sculptress” and even inspiring other women to use the tools at their disposal to pursue their own crafts – even with the humble kitchen as the starting point.

Despite butter production gradually shifting into factories during the 19th century, butter sculpting has kept its place in American agricultural displays – annual state fairs are often known for their butter sculptures, created to promote the local dairy industry. Despite industrialization, “[butter’s] image has remained tied to American pastoralism.” The resurgence of whipped dairy centerpieces could signify our yearning for ‘simpler’ times, and to reconnect to not only the processes behind our food but the land itself, a cottagecore response to rising costs and uncertain availability of the food and experiences that we have considered so everyday.