The act of gardening by its very nature requires human intervention and manipulation of environments. The word ‘gardening’ suggests that the garden is created by the gardener – and cannot exist of its own accord. Less controlled methods of cultivating land and plants for both human and non-human benefit have been practised all over the globe, but Western notions of gardening in particular have favoured gardens as an exhibition of skill, wealth and even power.1

An invention that enabled horticulturalists to further display their capabilities for control was the greenhouse. According to British gardener Percy Thrower (1913-1988), “Even a modestly sized and equipped greenhouse can extend one’s gardening horizons in quite a remarkable way. It allows one to grow many plants otherwise beyond one’s scope, and the opportunities it provides for home propagation add a new dimension to one’s gardening interests.”2 In this way, the greenhouse breaks down the boundaries and limitations imposed on gardeners by their own environment by separating the two with a pane of glass.

- 1. Holly Temple, “Plants, place and power: A conversation with Gabriella Hirst,” MOLD, (2024)

- 2. Percy Thrower, Percy Thrower’s Every Day Gardening in colour (Middlesex, England, Hamlyn, 1983) 222

“A kind of portable green-house”

Designs similar to the modern greenhouse have been in use for centuries, enabling civilizations to grow seasonal produce all year round. In the first century CE, “beds mounted on wheels…were moved into the sun, and on wintry days withdrawn under the cover of frames glazed with transparent stone” to grow cucumbers for the emperor Tiberius.3 In Korea, the construction of heated greenhouses was first described in a document written in the 15th century, predating the Western invention.4

Greenhouse innovation didn’t take off in Europe until the 17th century. The first stove-heated glasshouse in the UK was installed at Chelsea Physic Garden in 1723 to house plants collected from tropical climates.5 The link between greenhouses and Britain’s colonial history is inextricable. Greenhouses provided a way to artificially simulate appropriate environments for plants collected from overseas by so-called ‘plant hunters’ who otherwise would not survive the UK’s hostile climate. However, one of the biggest problems faced by plant hunters was not the care and maintenance of plants once they reached British soil, but actually ensuring they survived the journey.

- 3. Janick, Jules, and Harry Paris. “History of Controlled Environment Horticulture: Ancient Origins,” HortScience 57, 2 (2022): 236-238, https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI16169-21

- 4. Yoon, Sang Jun, and Jan Woudstra. “Advanced Horticultural Techniques in Korea: The Earliest Documented Greenhouses,” Garden History 35, no. 1 (2007): 68–84, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472355

- 5. “History of Chelsea Physic Garden”, Chelsea Physic Garden, https://www.chelseaphysicgarden.co.uk/about/history/

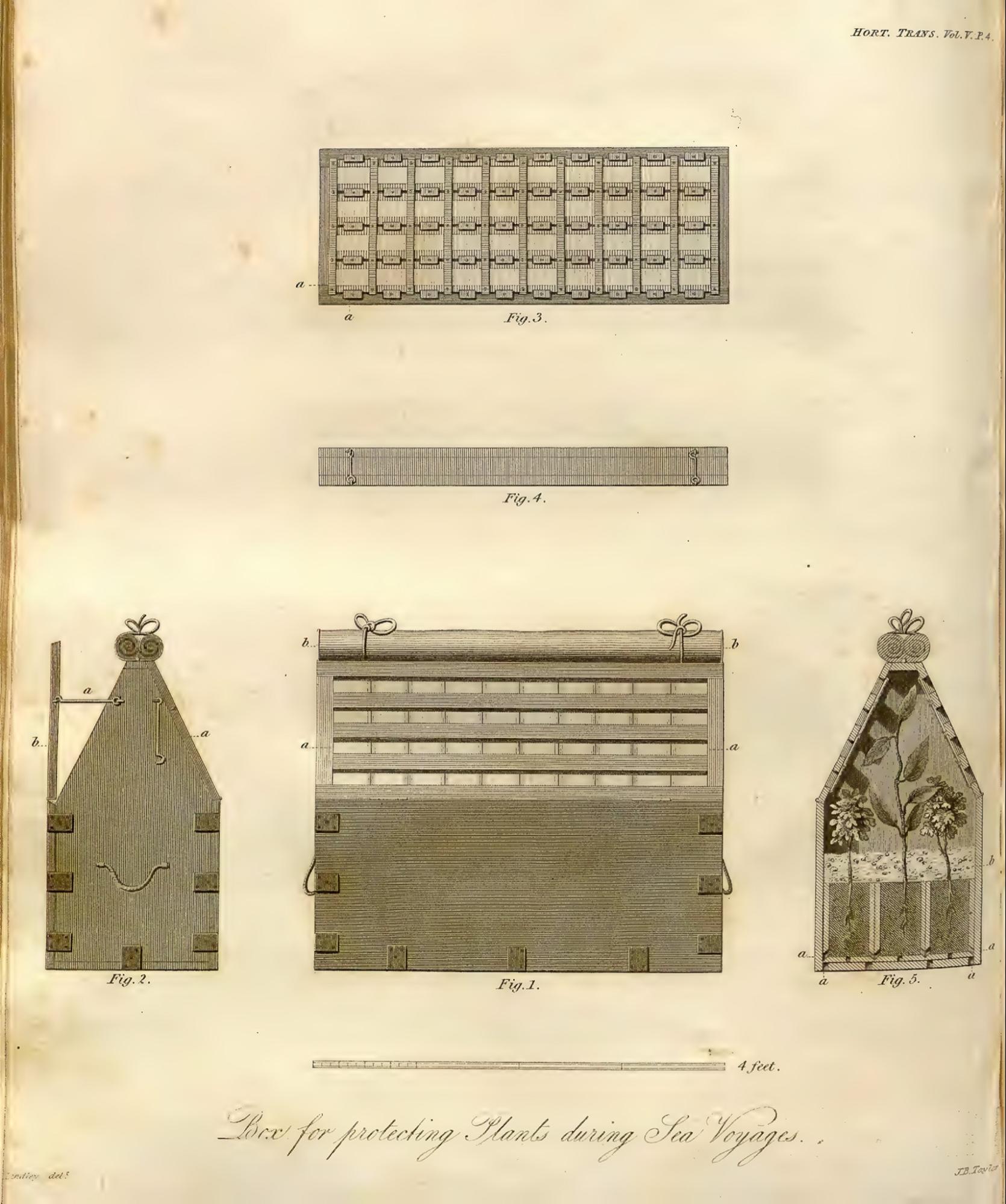

In an 1824 volume of Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London, John Lindley writes:

“The idea which seems to exist, that to tear a plant from its native soil, to plant it in fresh earth, to fasten it in a wooden case, and to put it on board a vessel under the care of some officer, is sufficient, is of all others the most erroneous, and has led to the most ruinous consequences.”6

- 6. John Lindley, “Instructions for Packing Living Plants in Foreign Countries, Especially within the Tropics; and Directions for Their Treatment during the Voyage to Europe,” Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London 5 (1824) 193.

He goes on to describe and recommend “a kind of portable green-house” in which he had received plants from Mauritius via Sir Robert Farquhar, “constructed in a very superior manner to any I have seen elsewhere.”7 The box included shutters which could be opened in good weather, and tarpaulin to protect the plants from sea spray on board the ship.

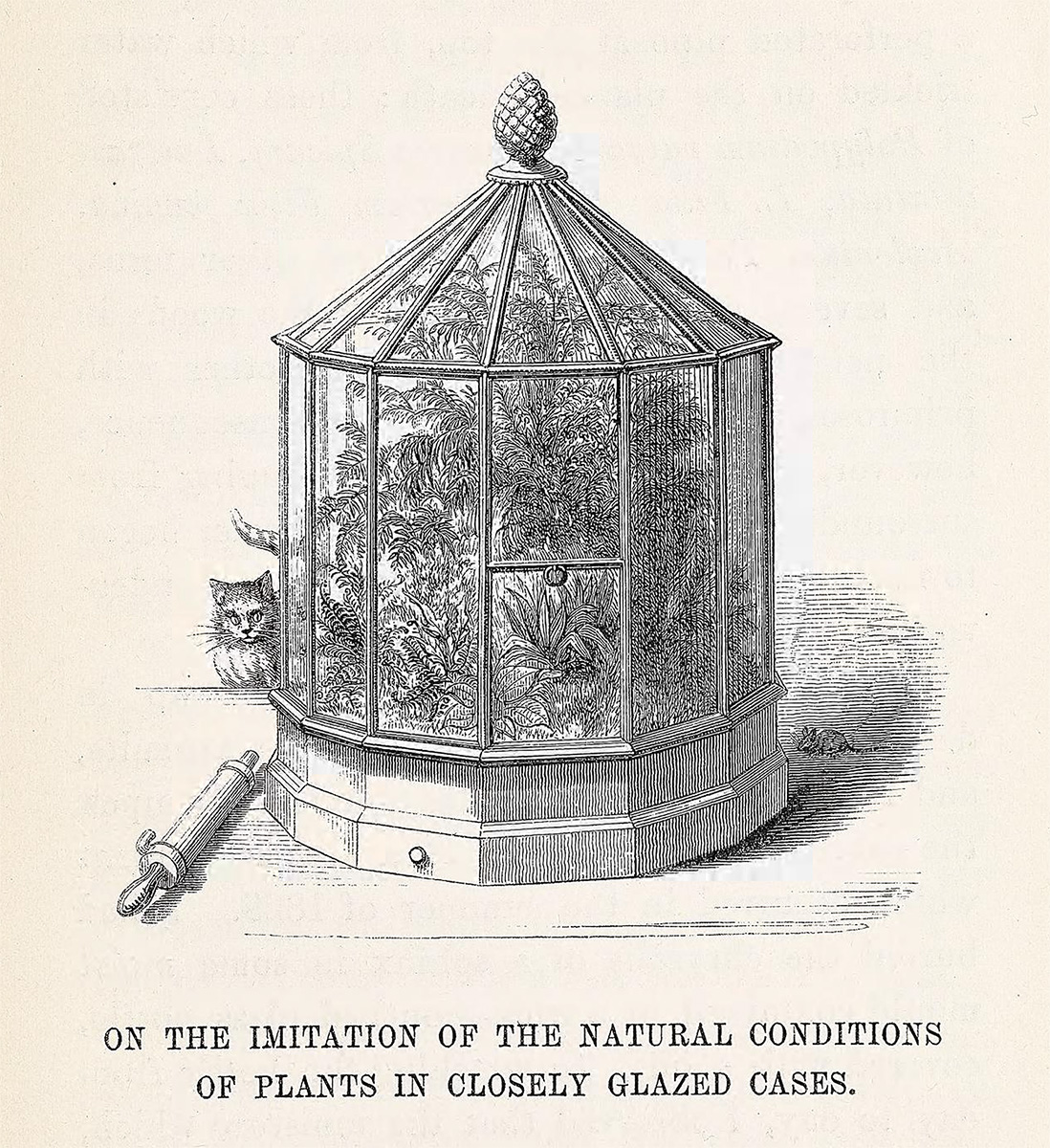

Just a few years later in the early 1840s came the Wardian case, designed by Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, what was essentially a forerunner of the terrarium. The sealed glass case not only sustained and protected plants on shipments, providing them with moisture from condensation, but also shielded imported plants from London’s air pollution. Much like a museum exhibit, the plants remained visible yet untouchable behind glass, shut off from the land and communities they’d once grown in.

Although not quite the same as a greenhouse – a Wardian case, much like a terrarium, created a closed environment in which a plant could be mostly self-sufficient. Plants were not designed to survive being uprooted and shipped across seas to a new continent, but the Wardian case made that a possibility. A technology for control over plants, people and place, it further enabled trade in the British Empire and the UK’s growing enthusiasm for tropical plants.

- 7. Lindley, “Instructions for Packing Living Plants in Foreign Countries,” 198.

Fern fever and most wanted weeds

The Wardian case supported the development of ‘fern fever’ or pteridomania which befell the Victorians. Despite the term’s connotations, fern fever wasn’t a debilitating illness, but rather a craze for ferns. During its peak, enthusiastic Victorians would collect and display the plants, even incorporating the plants’ distinct fronds in art and design throughout the era. Bagshaw Ward’s portable greenhouse was made popular with domestic fern enthusiasts who relied on the case to protect the plants from cities’ air pollution and provide them with the optimal environment to thrive.

The ‘fever’ was so contagious that those in rural areas of the UK would distribute the plants to people in cities that were desperate to remain on trend. Historian Dr. Sarah Whittingham writes that “…professional fern touts scoured the countryside for huge numbers of ferns, sent them up to the cities in hampers on trains, and then sold them in the streets, or hawked them from door to door.”8

- 8. Dr. Sarah Whittingham, “Fern Fever,” The British Pteridological Society (2014) https://ebps.org.uk/fern-fever/

The thirst for unusual plants as a symbol of fashion, status and wealth not only damaged native populations of plants in the UK, but also introduced new species to our gardens, some of which would become an unwelcome presence. Japanese knotweed, now infamous as an invasive plant in several continents, was introduced to the UK in 1850 by botanist Philip von Siebold. Donated to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the bamboo-like plant was promoted and sold as an ornamental plant to the general public. In an act of revenge for its abduction, knotweed became widespread, damaging buildings and roads and devastating biodiversity. It is now against the law in the UK to “plant or otherwise cause [it] to grow in the wild”.9 Removed from their original community, plants have always possessed the power of transformation, shaping both our cultural and natural ecosystems.

- 9. The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, Section 14 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/69/section/14.

From glasshouses to home gardens

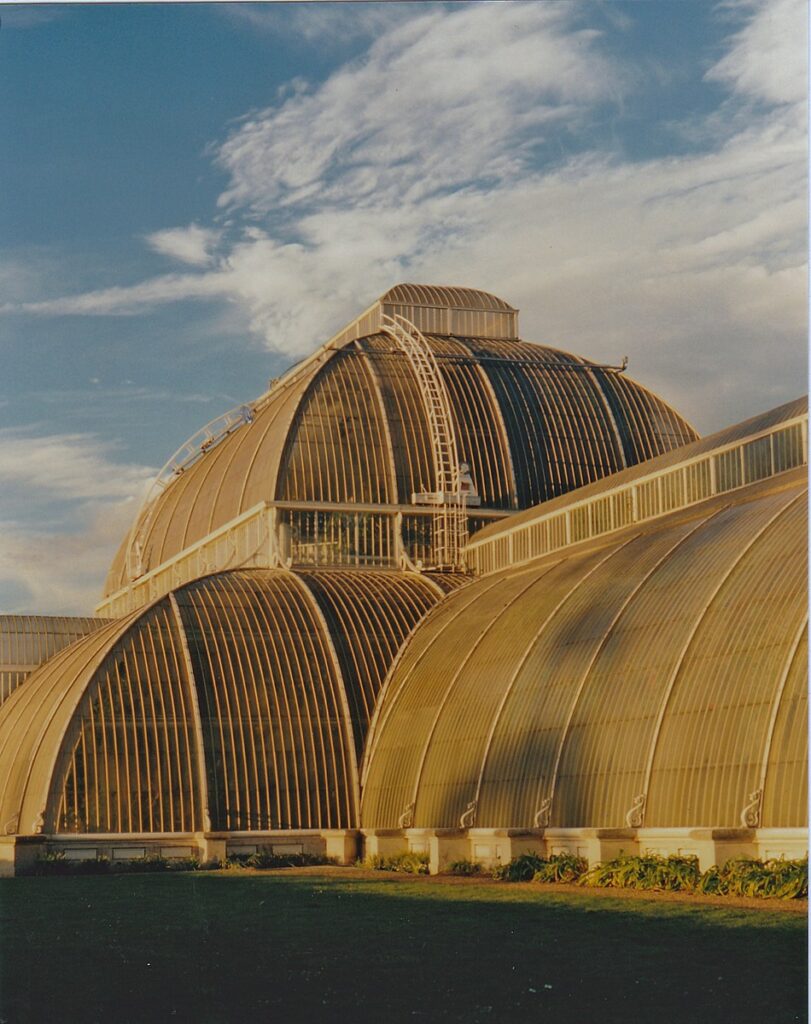

The Wardian case was “in regular use by Kew by 1847” with “commercially significant” plants being delivered to the Gardens or shipped to British colonies in the glass vestibules.10 Just the following year the Palm House, the first greenhouse to be built on its scale, was completed.

The design of the Palm House even resembles an upturned ship. This nod to architectural techniques borrowed from the ship-building industry also serves as a reminder of the origins of these plant collections and their colonial histories.11 There is no doubt that the huge glasshouse is a horticultural landmark -– not dissimilar to other palm houses such as of Hortus Botanicus, Amsterdam, a living museum that presents ‘discoveries’ from foreign lands to the general public.

- 10. Philippa Lewis, “The Wardian case: A history of plant transportation,” Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (2016) https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/the-wardian-case-a-history-of-plant-transportation

- 11. “Palm House”, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, https://www.kew.org/kew-gardens/whats-in-the-gardens/palm-house

Domestic glasshouses became more widespread as Western hunger for rare and exotic plants grew. From palms and ferns to fruits and flowers, those with the space and money could create a spectacle of their gardens for visitors, exhibiting their ability to source and afford the latest finds from across the globe. They fed the public imagination, presenting a picture of the feats one’s own garden could achieve with just a touch of industrial intervention.

Fast forward to today, greenhouses and controlled environments are commonplace in contemporary horticulture and agriculture, allowing growers of almost any skill and resource level to successfully raise plants in an artificial climate. From the global food system, botanical research, to allotments and windowsills, greenhouses allow us to control and manipulate growing conditions to achieve a desired result: we can speed up and increase germination and harvest, protect against pests and disease and reduce labour. In the introduction to Percy Thrower’s Every Day Gardening in colour, Thrower notes, “The owner, if he so wishes, can cheerfully leave his greenhouse for the span of a long working day knowing that, with such equipment, ventilation, heating and watering will all be looked after in his absence.”12

The collection of worldwide plant specimens and the development of the greenhouse has contributed to a vast bank of plant education and knowledge, ecological and environmental research and enabled us to witness and even interact with plants that we may never have had the chance to. But, can we credit greenhouses with supporting engagement with and vitality of ‘nature’? The imperial, exploitative origins of these practices beg to differ. Perhaps these structures have in fact contributed to distancing us from the nature right under our feet and on our doorstep. Particularly in the Western world, humans have long seen the natural environment as something to be manipulated, controlled and extracted for our benefit, but what happens if we let go?

- 12. Thrower, Every Day Gardening in colour, 9