In 2019, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF-UK) released The Future 50 Foods report, detailing 50 foods for “healthier people and a healthier planet”. The foods were selected based on their nutritional value, environmental impact, flavour, accessibility, ability to be integrated into our existing diets, and affordability.

While some foods in the list have enjoyed the spotlight in recent years (kale, lentils, quinoa and flax all find their place in the report) the first category in the report is Algae, which names both laver and wakame seaweed as strong contenders for a natural meat replacement. While seaweed is an essential ingredient in diets across the world, in the West, it seems that seaweed has yet to achieve its full potential.

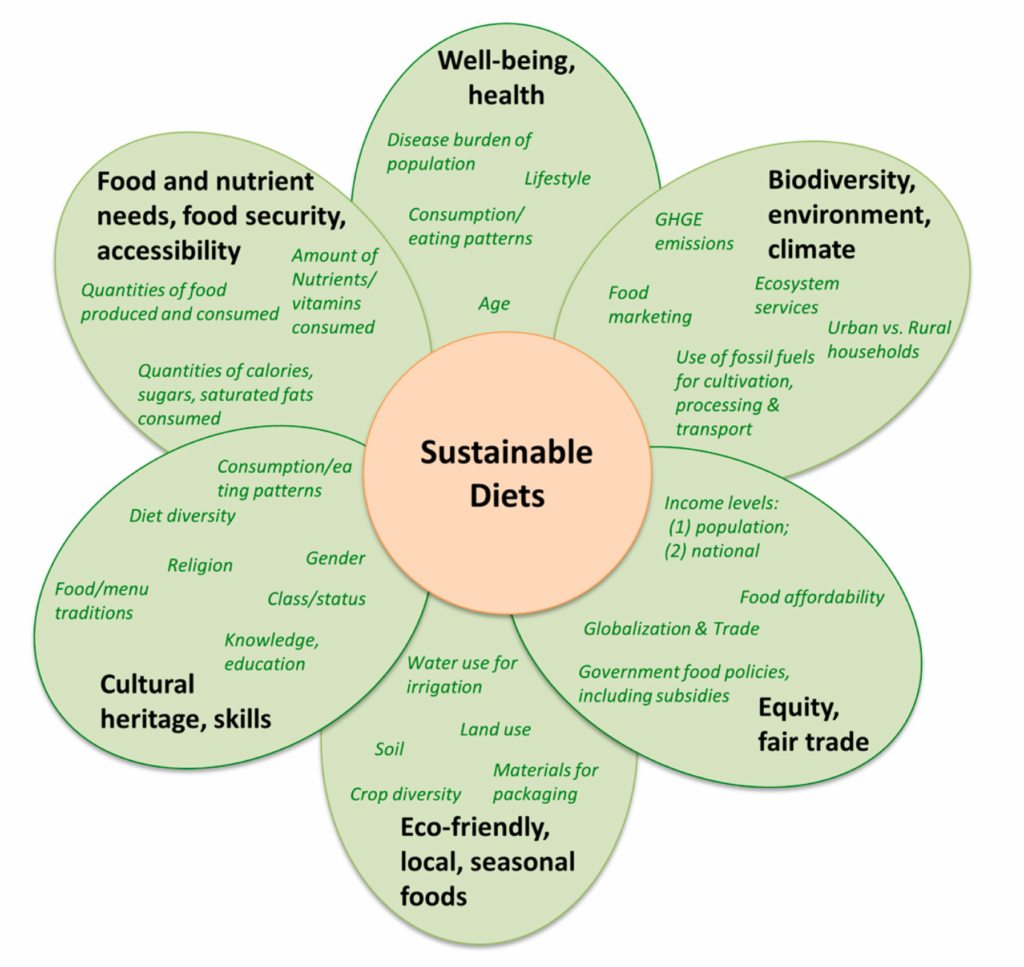

This diagram, first included in the article “Understanding Sustainable Diets: A Descriptive Analysis of the Determinants and Processes That Influence Diets and Their Impact on Health, Food Security, and Environmental Sustainability”, illustrates “the key components, determinants, factors and processes of a sustainable diet”. 1 We know by now that the process of providing food systems and food products that are sustainable for both planet and people is highly nuanced, and each component influences and depends on another. For example, class and status affect food security and accessibility, and the state of the environment and climate affects food affordability.

Like many other foods, seaweed production is being threatened by climate change, specifically by the rise of sea temperatures and acidification. However, seaweed itself could also be a solution to not only mitigating climate change, but also improving local economies and our health.

FROM INDIGENOUS FOOD SOURCE TO HEALTHFOOD INNOVATION

Currently, the largest seaweed-producing countries are China, Indonesia and the Philippines. However, the earliest written record of humans’ usage of seaweed originates in China around 1700 years ago. 2 Initially harvested for use as food, feed, or for medicinal purposes, industrial uses for macroalgae (seaweed) have recently emerged, including as a replacement for fossil fuels and plastics.

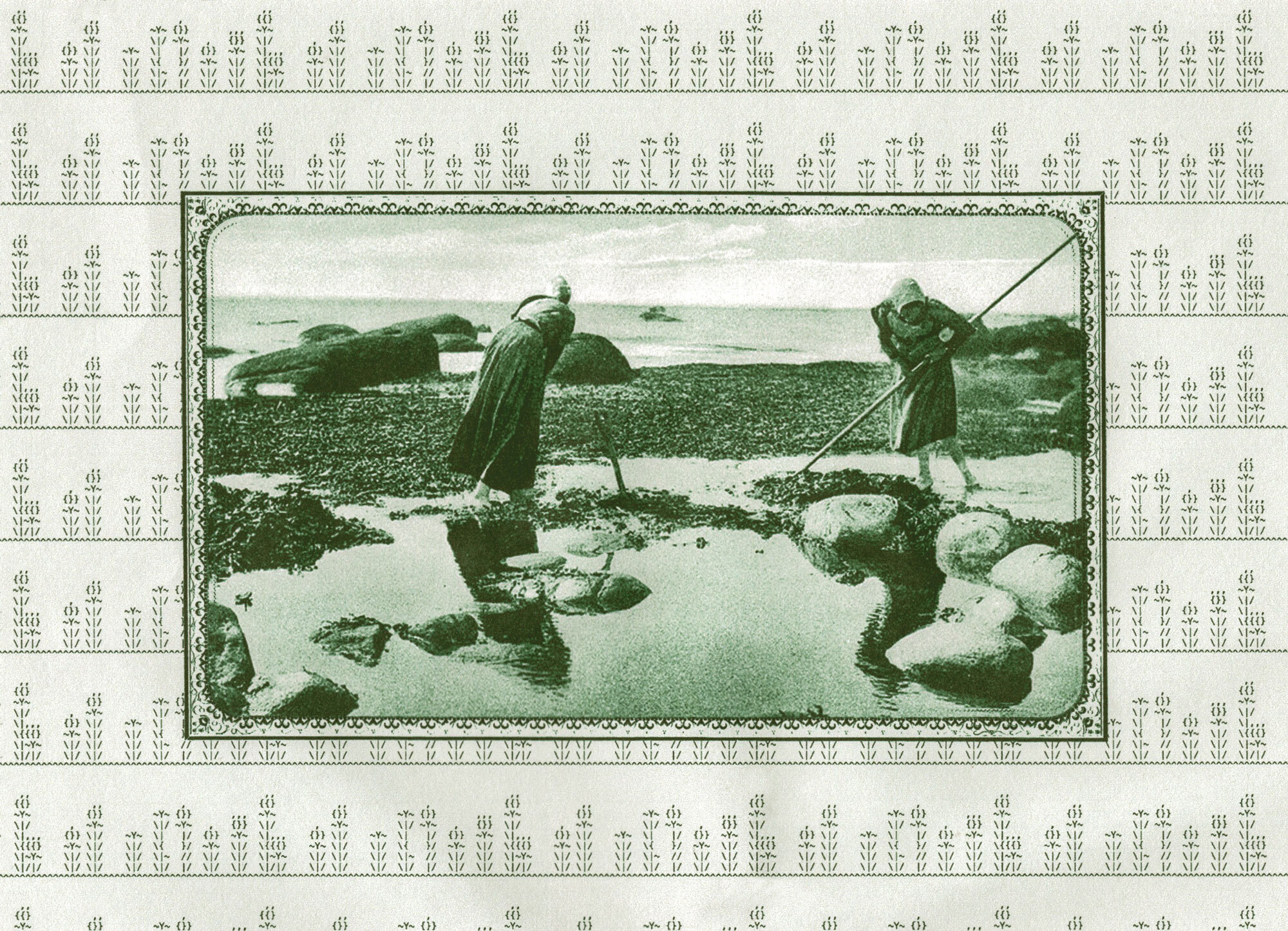

As people began to migrate around the world, so did the customs of seaweed harvesting, so that now European countries such as Norway, Iceland, France and the UK have their own histories of seaweed harvesting, as well as the US and Canada.

- 2. “Seaweed production: overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity”, European Journal of Phycology, Buschmann, et al. 2017

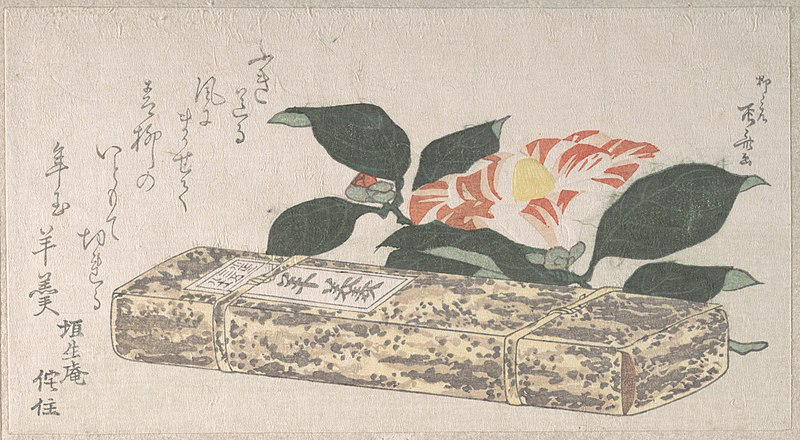

For centuries, seaweed has been harvested for its thickening properties, or as an everyday foodstuff itself. A woodblock print created in 1811 by Japanese artist Ryūryūkyo Shinsai displays a block of yōkan, a red bean jelly made with agar –– a gelling agent extracted from red algae. Other popular examples of seaweed include purple laver, the dried sheets of which are known as nori in Japanese cuisine; kombu (Japan) or haidai (China), a leathery brown seaweed often added to sauces, soups or tea. Histories of seaweed in local cuisines have travelled as far as Wales, where laverbread or bara lawr (a boiled laver seaweed puree) has been consumed since at least the 17th century.

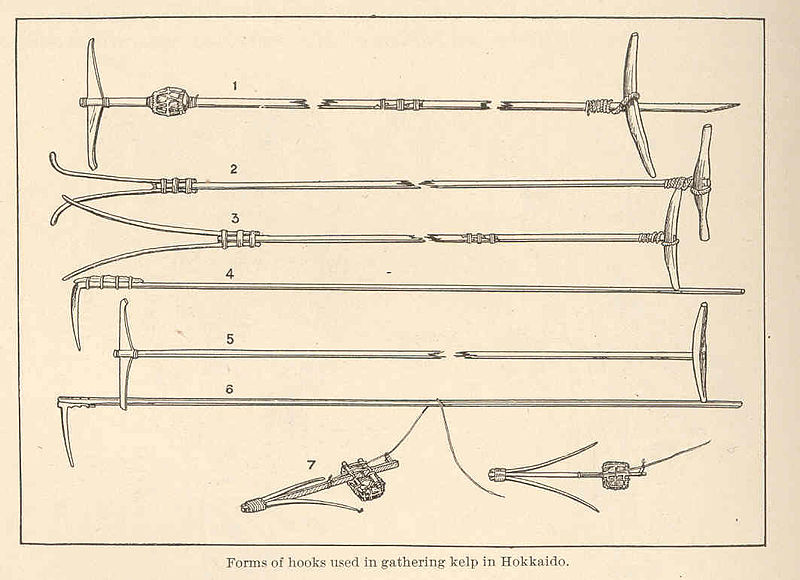

World-over, seaweed has had a tangled history as an Indigenous food source for coastal communities before losing favour against more readily available foods. In Alaska, the dAXunhyuu, or Eyak people, hunted salmon and harvested seaweed such as kelp, but these practices have been appropriated and almost erased by colonialism. Native Hawaiians have long valued a red algae known as limu kohu, which is now in decline due to changing environmental factors and its acquired taste, while in Norway, Vikings favoured seaweed for its nutritional content.

In the 21st century, seaweed has regained popularity as a health food or innovative ingredient added to restaurant menus –– and now is considered a potential solution to climate change.

BUILDING A BLUE ECONOMY

The global expansion of the seaweed industry has seen it farmed as not only a food source but also to be used in organic fertiliser, biofuel, new bioplastics, and in animal feed — with the latter holding the potential to lower methane emissions of cattle.

The argument for increasing cultivation of seaweed not only includes the organisms’ endless possibilities for human use, but also their ability to sequester carbon in the ocean. Acting as a “CO2 sink”, seaweed absorbs carbon during its lifespan — but if left to decay, this carbon could be released back into the atmosphere.

This highlights an urgent need for current and future seaweed cultivation to consider end-of-life solutions that prioritise sustainable harvesting and use, rather than discarding the algae once matured. Currently, seaweed is not recognised by the Blue Carbon Initiative, a global program aiming to restore coastal and marine ecosystems to mitigate climate change. “Blue carbon” is defined as the carbon captured and stored in these ecosystems — namely mangroves, marshes and seagrasses.

Pull To Refresh is a start-up setting out to grow and sink seaweed, burying carbon in the deep sea using solar-powered vessels. Their website promises “durable ocean carbon sequestration of more than 100 years”, and a button encourages businesses to PURCHASE EMISSION REVERSAL — to balance their carbon emissions. In an article for MIT Technology Review, James Temple highlights that “no one knows what the ecological impact of depositing billions of tons of dead biomass on sea floor would be.” Do we really know enough about these complex organisms to deposit them out at sea at such a large scale — and what happens when the period of carbon sequestration ends? Sinking seaweed as a solution to climate change — which sounds a little too similar to the “planting a tree” promise made by many worldwide corporations — has been in discussion for several years, but there are certainly more beneficial uses to seaweed than disposing of it once it has done its initial job for us.

Portugal-based ALGAplus define themselves as “marine agronomists”, dedicated to the sustainable and organic-certified farming of seaweed. Using the Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) concept, ALGAplus cultivates several species (e.g. fish, seaweed and shellfish) in close proximity to create a balanced and circular system that reduces waste.

GreenWave, a USA non-profit organization, is building regenerative ocean farms to create a “blue economy”— training farmers, developing technologies and connecting farmers with buyers across coastal communities. Meanwhile, UK-based Notpla are making packaging materials from seaweed that biodegrade in 4-6 weeks — including edible drinks and sauce sachets.

RESTORATION OR EXPLOITATION?

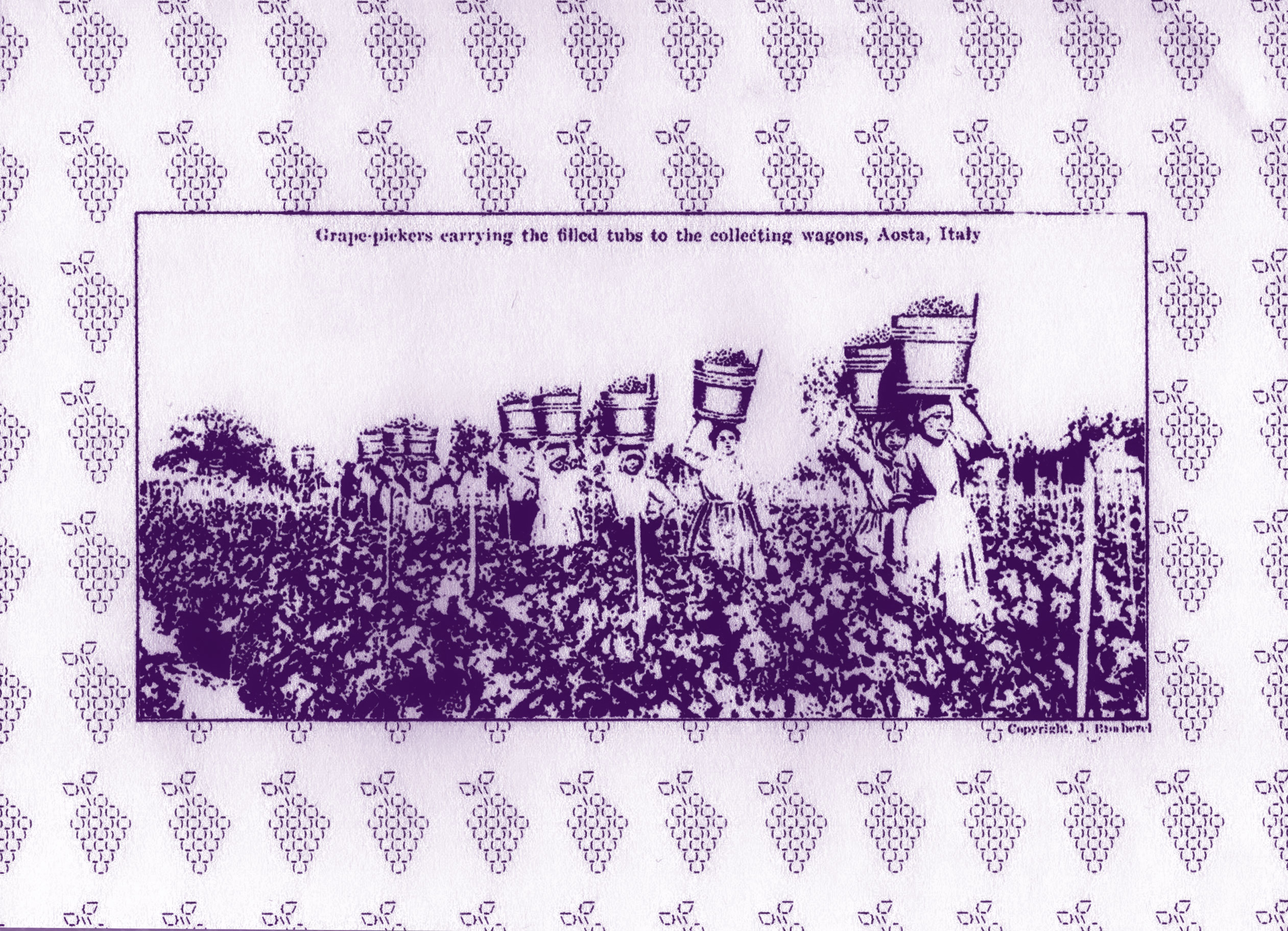

The histories, narratives and values of seaweed all over the globe are as complex as our own. Despite recent innovations, seaweed cultivation across much of the world remains low-technology and high in labour, with the understanding of this fast-growing, diverse and useful plant passed down through native knowledge –– how can we ensure workers are paid and treated fairly, especially if demand begins to grow? This also begs the question of whether governments and authorities worldwide will support seaweed farming and harvesting as a solution to mitigate climate change, with reports that permits are difficult to acquire.

Climate-focused innovations are needed, but we should acknowledge and learn from the indigenous practices and rich histories of seaweed cultivation across the world -– something GreenWave is doing through its support of Indigenous Shinnecock Kelp Farmers in New York. In Cordova, Alaska, the Native Conservancy are working to preserve Indigenous food sovereignty and natural habitats through community programs as well.

Even in the UK, seaweed such as dulse (now registered on the Ark of Taste as an endangered food) formed part of a regular diet for centuries, but is now at risk of being forgotten despite emerging local seaweed farms. The possibilities for the future of seaweed in our lives are exciting and rich, but we must remain respectful of the delicate ecosystems that they are a part of, and listen to the voices of those who have waded this path long before us to ensure this is a process of restoration, not exploitation.