The language used to describe methods of care within Western gardening practices often feel like they are implicating the participant in violent acts towards nature. Deadheading, pruning, and weeding for example, are apparatuses of control, their names betraying the use of unnatural, human influence to manipulate a desired outcome. In her investigation into the histories of Western gardening, artist Gabriella Hirst identifies the ‘Atom Bomb’ rose cultivar as an interscalar vehicle, a term coined by anthropologist and historian Gabrielle Hecht to describe a “means of connecting stories and scales usually kept apart.”1 Through her practice, Hirst parallels the narrative of the rose with the dispossession of Australian land, historically disregarded as “not gardened” for not following Western norms of cultivation.

- 1.Hecht, G. (2018) ‘Interscalar vehicles for an African anthropocene: On waste, temporality, and violence’, Cultural Anthropology, 33(1), pp. 109–141. doi:10.14506/ca33.1.05.

The ‘Atom Bomb’ rose is at the centre of Hirst’s How To Make A Bomb, an ongoing project consisting of public rose grafting workshops which examine the entangled histories of horticulture, power, and nuclear colonialism. Bred in 1953 – coincidentally the same year that Britain conducted nuclear tests at Emu Field in South Australia, Hirst tells me she first came across the rose almost ten years ago.2 Now a rare cultivar, she managed to find a nursery in Florence, Italy that had one of the roses in their collection – and kindly grafted a plant for her. In a conversation from earlier this spring, Hirst tells me that, “There’s very little information on it out there. It fell from popularity after initial success, and there are various reasons for that. Potentially because of changing attitudes towards nuclear mania, this kind of, actual excitement about things that were related to atomic blasts…and then it popped up in these unexpected marketplaces.”

- 2. ‘Operation Totem – 1953’ Atomic Forum: An illustrated history of nuclear weapons. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20090105213805/http://www.atomicforum.org/uk/totem.html Archived from the original on 5 January 2009.

The so-called Atomic Age after World War II sold a “dream” of the possibilities of nuclear power, even nuclear food preservation and medicine, but brought with it the ever-present risk of atomic warfare and destruction. Nuclear weapons testing at the Nevada Test Site attracted tourists keen to watch the blasts, which led to the events being advertised (and charged for) as such. With this context, it is less shocking that a garden plant be named after such a weapon.

In a recent conversation, Hirst tells me of the discomfort felt when bringing her rare ‘Atom Bomb’ rose through the airport in her hand luggage. “I was like, Is it the language of it? Or is it the physicality of it? Or is it the symbolism of it?…But I think it was that moment of crossing a nation state boundary with this plant that I really started to be like, Oh, the word in this is so much more laden with the history of botanical colonialism.” In her research she continued to piece together links between Britain’s nuclear testing on Australian land, the ‘Atom Bomb’ rose and nuclear weaponry. Eventually, this led to an invitation from curator Warren Harper to develop the research further at The Old Waterworks in Southend-on-Sea, Essex. Though coincidental, Southend’s nuclear history would become significant in the project and Hirst’s resulting work. Just around the region’s coast lies Foulness Island, where Britain assembled its first ever atomic bomb before shipping it to be tested on the Montebello Islands, off the north-west coast of Australia in 1952 (just a year before the ‘Atom Bomb’ rose was bred).3

- 3.Cocroft, W. (2022) ‘6 Places That Tell the Story of Operation Hurricane’, The Historic England Blog.

How To Make A Bomb developed into a series of rose-grafting workshops, inviting the public to graft their very own ‘Atom Bomb’ rose from the one specimen retrieved from Italy –– a skill Hirst learned during a visit to a rose nursery in the UK. She tells me that the act of grafting roses is one that can provide insight into the dynamics of global power. “I was thinking about rose breeding as this form of cultivation that bends this plant to a specific desire, and [asking], ‘Is that related to control?’ And I was already thinking about nuclear weapon development, and this idea of almost gardening atomic materials into a form to produce a specific effect of control or dominance. And then the rose – this highly manipulated plant that’s come to symbolise passion and romance, and also is used as the national symbol of Britain and the US.”

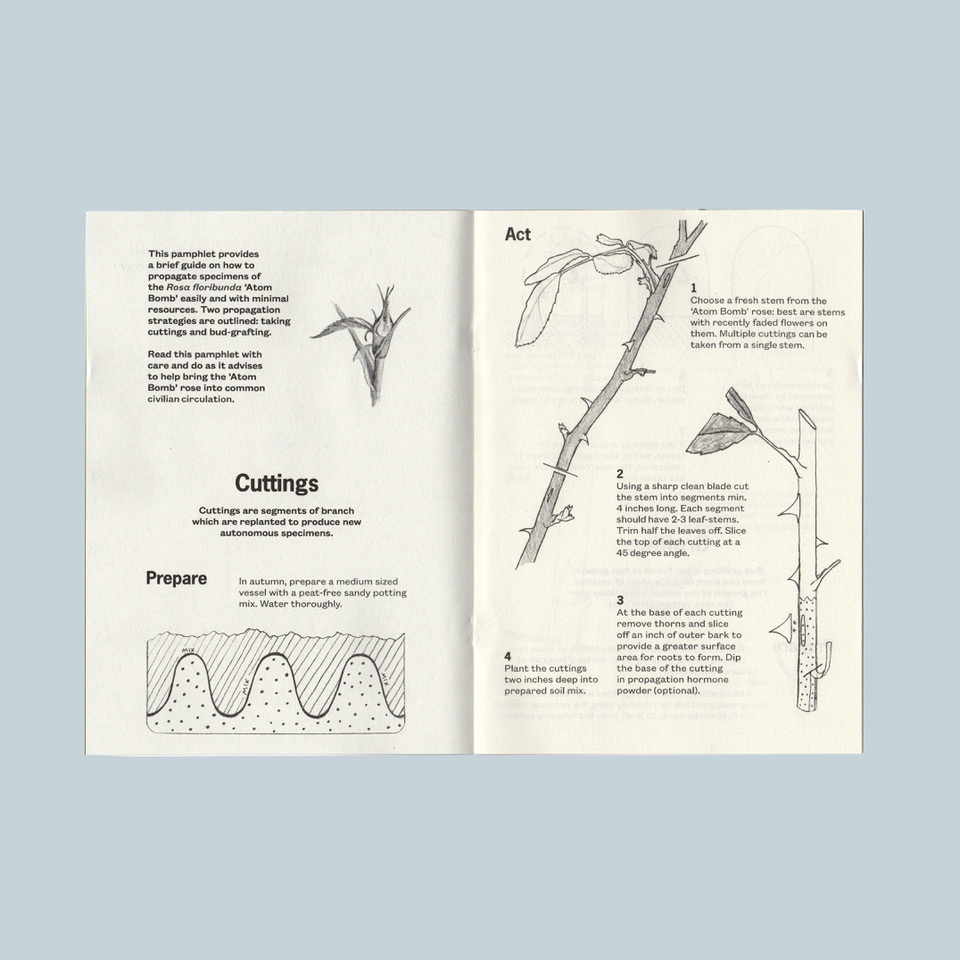

Because the ‘Atomic Bomb’ was bred during a time when chemicals were widely used in gardening to support growth and prevent disease, Hirst was warned against propagating the rose by experts, as cultivating it without those products could leave it susceptible to disease. However, the workshops have enabled Hirst to increase the population of the ‘Atom Bomb’ rose, and alongside an accompanying ‘How To Make A Bomb’ instructional pamphlet, encourage members of the public to distribute their roses and plant them in public or private gardens. According to Hirst’s website, there are “currently an unknown number of ‘Atom Bomb’ roses growing in British soils.”4

- 4. Hirst, G. ‘How To Make A Bomb’, Gabriella Hirst.

In 2021, Gabriella Hirst and Warren Harper installed a public installation in the nearby Gunners Park – a former Ministry of Defence site. An English Garden consisted of ‘Atom Bomb’ roses planted into a hexagonal bed which referenced the shape of one of the military buildings on Foulness Island. Next to this, a curved bed was planted with ‘Cliffs of Dover’ irises (also introduced in 1953), geographically facing the true Cliffs of Dover to the south-east. Reminding visitors of the nuclear weapons assembled in this area before being shipped to Indigenous Lands in Australia, three benches around the planting were fixed with plaques explaining the significance of the site, and Britain’s role in nuclear armament and colonialism – creating a quiet, yet confronting space for learning and dialogue.

Unfortunately, after only a matter of weeks, the work was forcibly removed after pressure from local Conservative politicians, who took offence at the piece and considered it a “far left-wing attack”. It was noted that the work “received no complaints from the public”.

One councillor argued that the UK’s commitment to nuclear armament expansions was an act of care for the nation – which prompted Hirst to question how we view care, and what we care for: “Where are the lines between when a weapon is a provocation to more violence and when it’s supposedly protection? When is care suffocating? When does care do more damage than not?”

After An English Garden’s removal, Hirst and Harper continued their collaboration, facilitating more rose-grafting workshops and encouraging the public to plant their ‘Atom Bomb’ in their own gardens. The workshops involve a presentation from Hirst introducing the layers of context around the rose and the histories and stories uncovered, but also pass on the horticultural skill of grafting, and the attention needed to nurture your rose and its surroundings, wherever you plant it.

Gabriella Hirst, An English GardenThere are gardens that must be tended to.