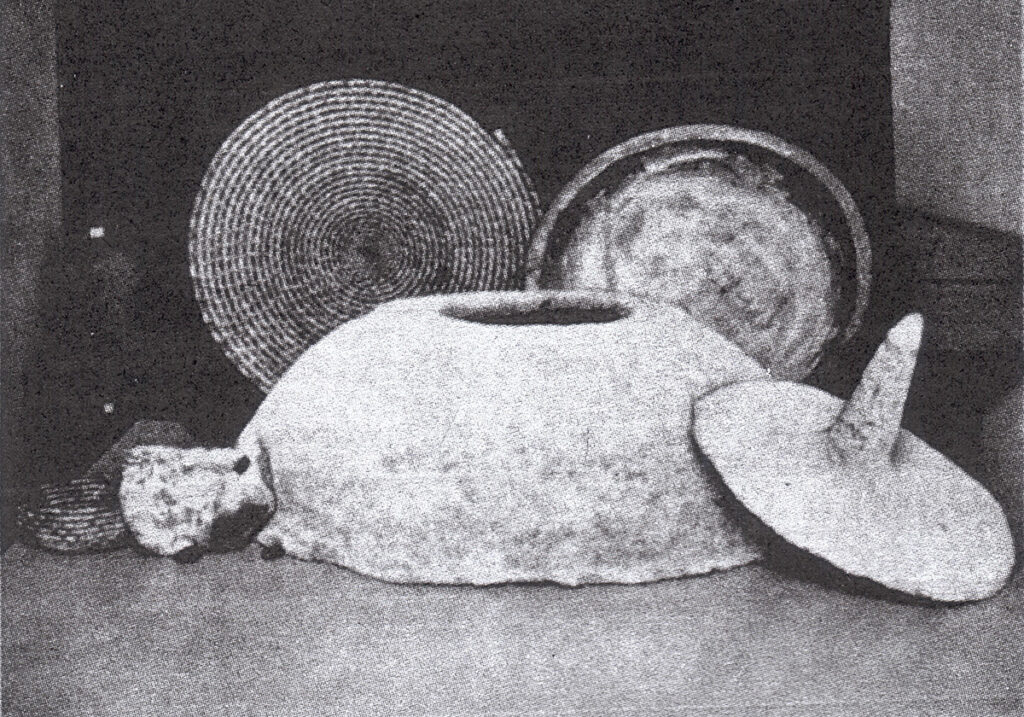

Wooden bowl battiyeh, woven basket mikfaya,

clay oven tabun, a bed of hot rocks radaf,

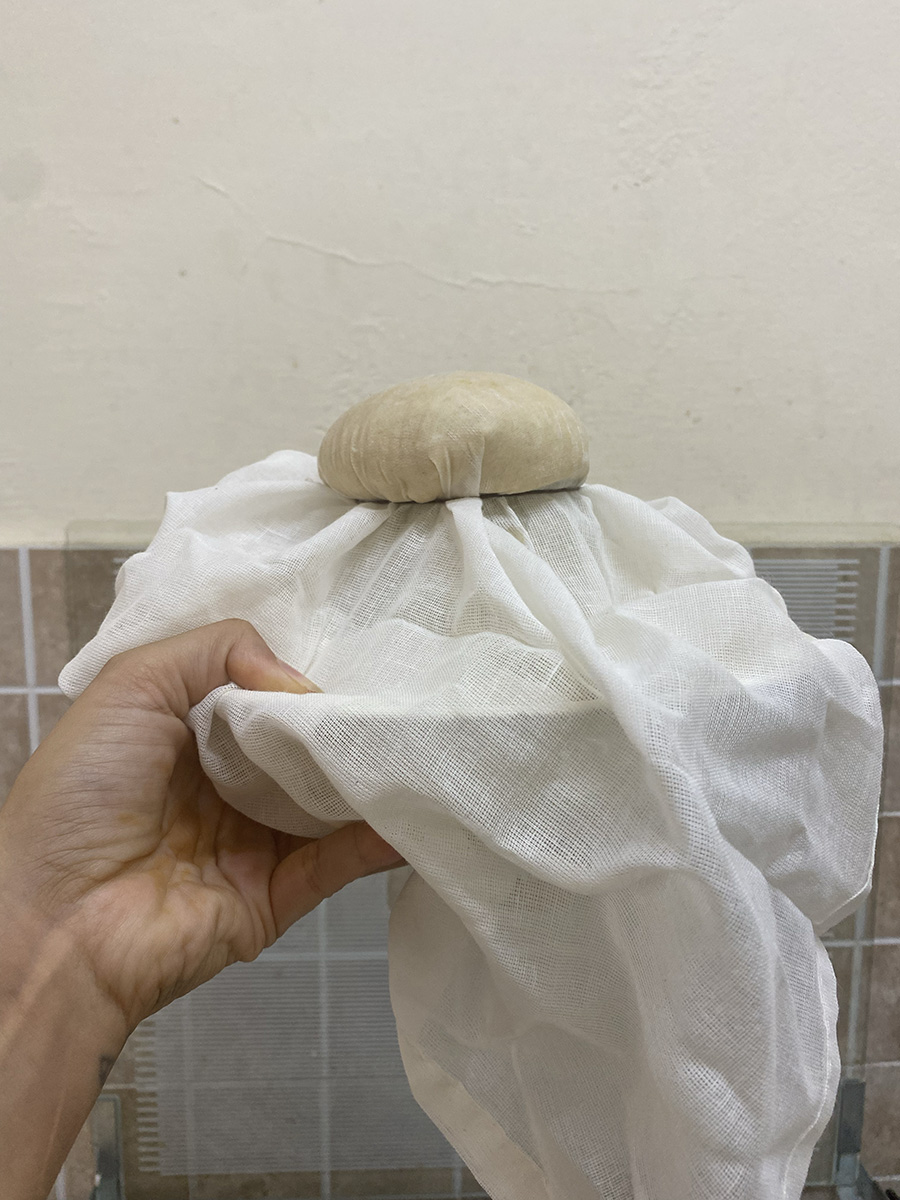

pillow mold m’khad, a convex metal dome saaj.

Sitti Jamila’s crumbling stone barn exists in the architecture of my memories; while her infinitely wrinkled, smiling face surrounded with coins is immortalized in the one photo I have of her. It has been more than a few decades now, but I’ll never forget the desiccated furry skeleton of a white cat worn into the path to the almond orchard. I would leap over it as I ran past her long unused tabun, where it still sits shrouded in shadows, overgrown with weeds and indifference to its utility. Many early summers were spent climbing up onto rusted oil barrels with cousins, stretching our growing limbs towards fuzzy green capsules filled with smooth white baby almonds, hours of cracking and peeling, and peeling again. So much work for a morsel, as with many, most, (all?) things we homosapiens have deemed food throughout our very long yet brief timeline.

Processing, cycling, becoming til they become, and then, in a moment, they are transformed into something else yet again, and so on, forever. Timeworn cycles of the lives of Earth’s beings—from something to something else—we perpetually transform until we don’t, or until we think we can’t or just won’t. Plants show us otherwise by always becoming again, understanding when to become, how to become, without the deadly arrogance of ‘knowing’. Even with all of our pedantic human meddling, they persevere, or in the case of wheat, with our meddling we became, together. Lately on earth, the plants have been blooming out of time, out of step with their own cycles, reflecting back the ways the dominant species on this planet is out of step with its own place in the system.

All this to say: wheat began where my blood began. I tend to think that my blood carries the same language as the plants from where I came, that I too, carry some of the same DNA as ancient wheat; seeds stored in this flesh sack. I am young, but parts of me are ancient. I am only slightly different from the grasses that just happened to have the right characteristics to be coaxed into becoming the backbone of human energy consumption.

Tawfiq Canaan“It was an old belief, known still to many Arabs of Palestine, that the tree of ‘knowledge of good and evil,’ which stood in the midst of the garden of Eden, was a wheat tree.”

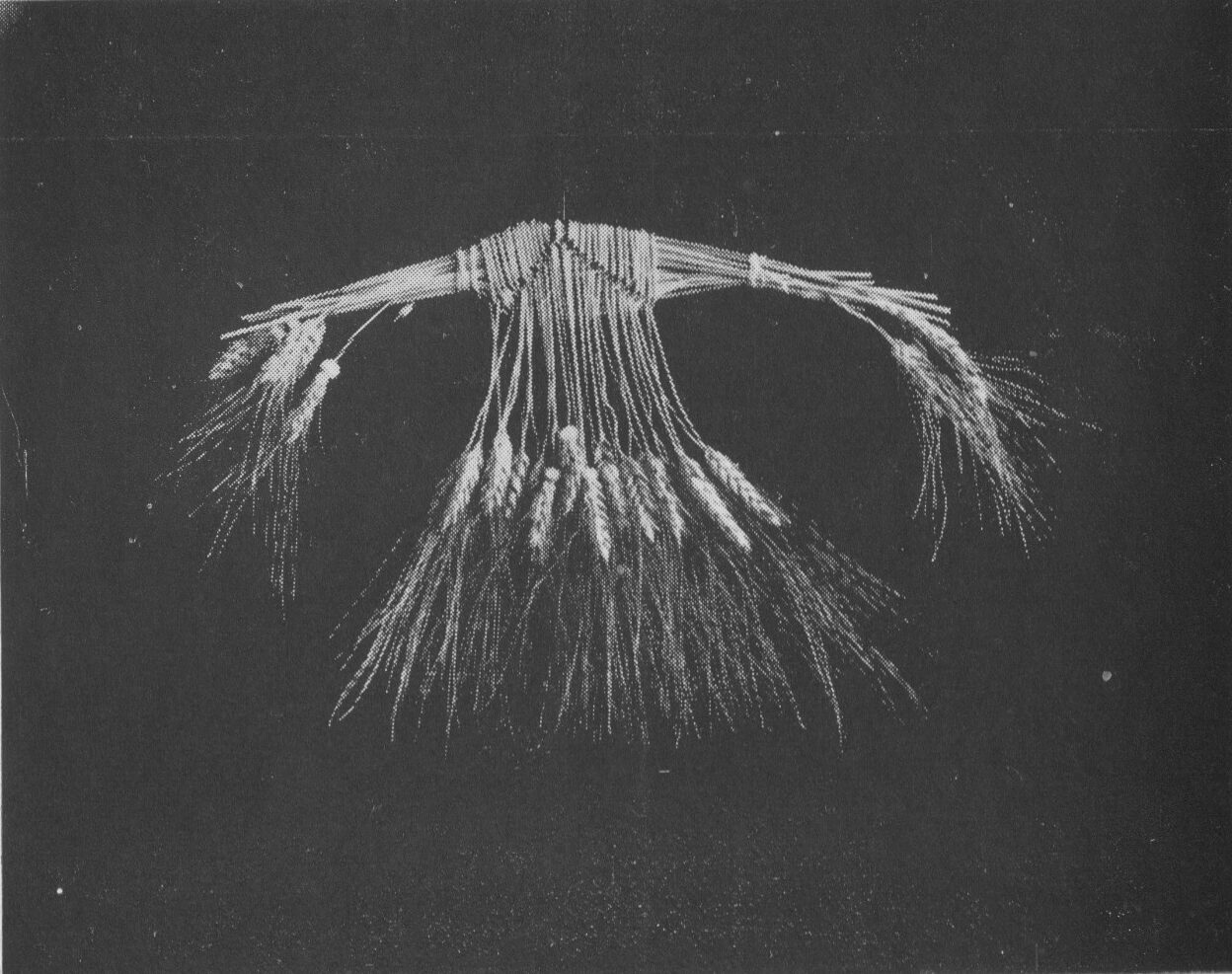

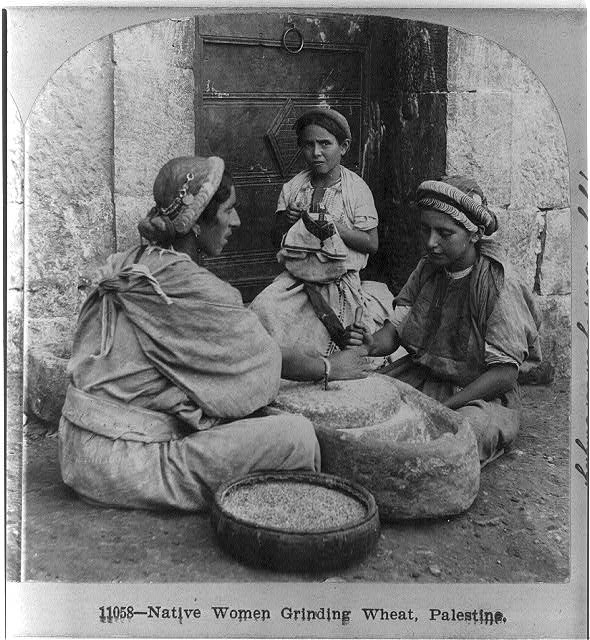

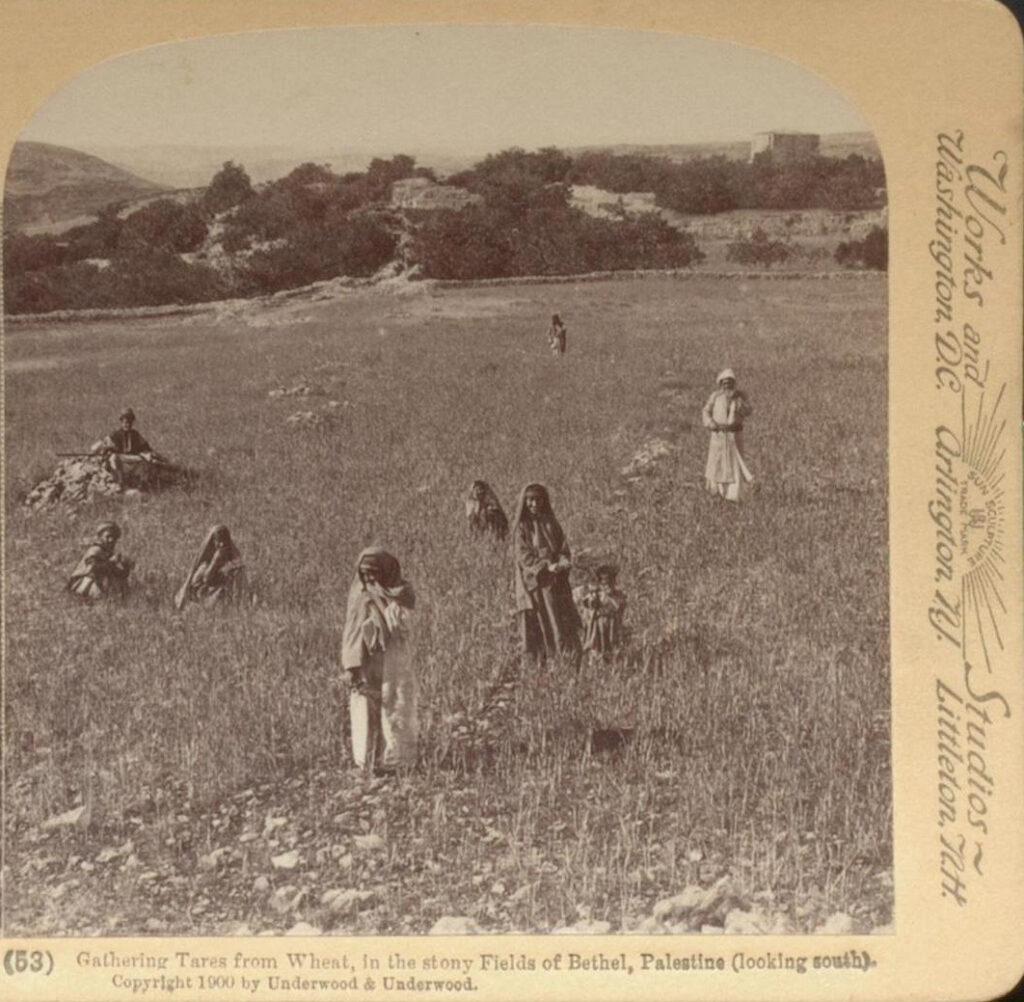

It has been 14,000 years since the oldest bread (that we know of) was fire baked on hot stones by my Natufian ancestors, a remnant of which was found only recently in an ancient hearth in the area now called the Levant.1 Archaeologists credit these hunter gatherers of pre-Abrahamic Palestine, with using primitive sickles to harvest wild cereals—the grass family predecessors to wheats and maize—as well as with developing mortars that allowed them to produce a finer flour that eventually led to the bread of today. As one evolutionary development tends to lead to another, these technological advancements laid the groundwork for their descendants, and what would go on to become more developed and stationary agricultural societies. Natufians are believed to have developed the semi-sedentary settlements that interwove the practices of hunting and gathering with the early agricultural economy.2 This interweaving occurred a few thousand years before wheat was thoroughly domesticated to become the backbone of human consumption/civilization, and several thousand years before the invention of agriculture necessitated this restructuring of human relationship to movement and the land for its sustenance. First the Natufians, then the Ghassulians, then the Canaanites—all well before the times of Abraham and the monotheism that holds wheat in a most venerable position—were milling some form of wild wheats and mixing them with other plants and vegetables, then cooking the slurry on hot stones in the precursor to the tabun oven, which itself evolved into the communal oven and gathering space of Palestinian village society.

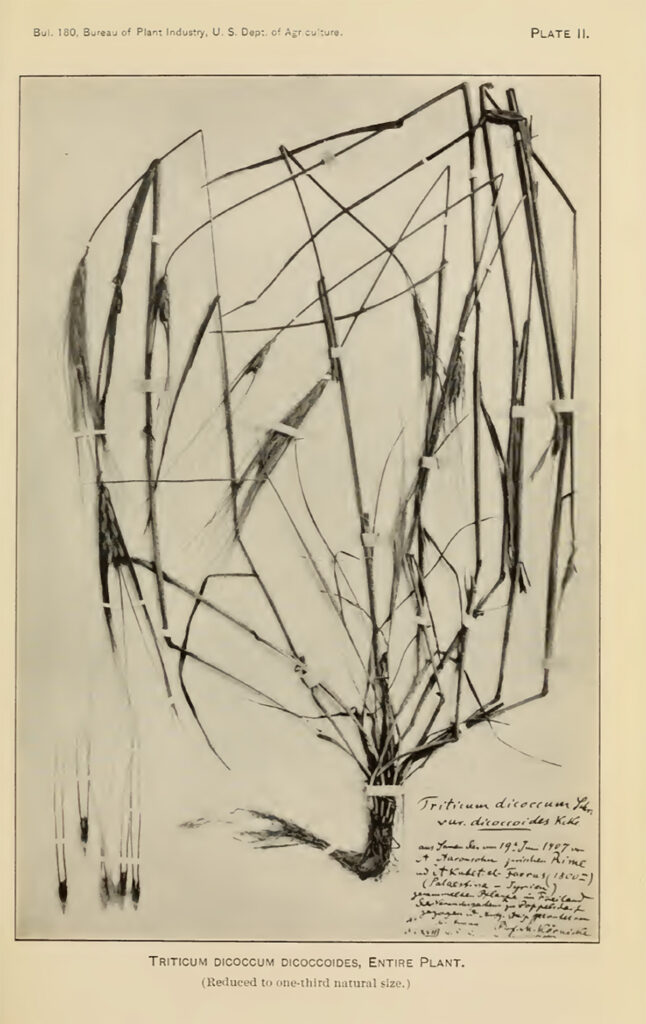

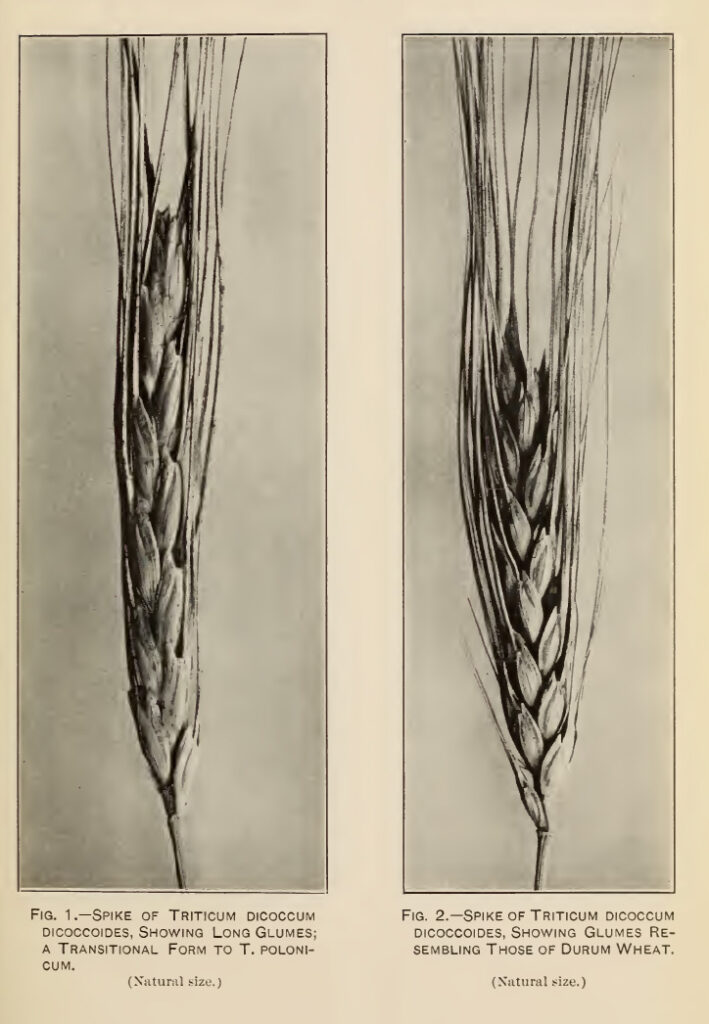

Emmer, Triticum dicoccum, is scientifically believed to be the sole contender for the wild prototype from which the majority of wheat grown and used for human consumption globally today evolved, with the assistance of our several thousand-year-old ancestors.3 Modern emmer is found to date back to the late Neolithic period, to the Fertile Crescent. This variety was selected and cultivated, co-evolving with ruminants, agriculture, and early civilization, paving the way for human diets thousands of years into the future, to become the foundation of human culture as we know it. Today, wheat fields occupy more land globally than any other crop.4

Reading through descriptions of Canaanite culture and customs, it is not difficult for me to see where my own family, members of today’s Palestinian fellaheen (loosely translated as ‘peasants’) inherited their culinary mannerisms, eating traditions, and relationships and practices around wheat and breadmaking. Planting, threshing, grinding, kneeling, kneading, shaping…though thousands of years separate Canaanites from fellaheen, not even the gestures and movements have changed. The people shaped the wheat, and in turn the wheat shaped the dough, the land and the people—changing life on earth forever more. zionist mythology that originated in the late 19th century claims that Palestinians are a newly nationalistic group of Arabs who originally migrated from the Gulf, yet our DNA and cultural practices clearly exhibit our inextricable ties to this land, in an undeniable manifestation of our indigeneity, thousands of years prior to the time of the Book, or socio-linguistic Arabization to the Levant in the 7th century. The only truth to be found in this colonially distorted narrative, is that prior to European colonization, our people didn’t see the need for nations and borders upon our lands.

Crowfoot & Baldensperger“Wheat is noble, Wheat is holy. Wheat came down from heaven in seven napkins (Al qamh nizil fi sab’a manadil).”

For thousands of years, bread has constituted the most important food of not only the fellaheen of the Levant, but the bedouin as well. Both cultural groups, considered to be the poor people of the land, were living primarily on bread, fresh spring water, and wild foraged greens. They supplemented with dairy products and meat when available, or on special occasions. In more recent history, prior to 1948, the most esteemed bread was made of emmer wheat flour, though many fellaheen prepared their dough of emmer flour mixed with barley, or for those of even lesser means, barley alone. Meanwhile the bedouin were known for their ‘black’ bread made of the seeds of samh (Mesembryanthemum forskalei Hochst), a succulent like plant found in desert areas where they lived and grazed their herds.5 Bread was of utmost importance for the people in the land before and during Biblical times, and it continues to be—the average contemporary Palestinian consumes around 120 kg of bread per year.6

This scenario has by now taken place in most places on Earth due to capitalism’s insatiable dependence on globalization, industrialization, and voracious extraction. In Palestine it happened via strategic and expedient colonial organization, with the expressed interest of obliterating and replacing the indigenous way of life to create space for a settler colonial vision of Utopia for some in the Holy Land. In spite of this, many of the traditions and practices of our ancestors from several time periods prior to the present, are manifest in the beliefs, mannerisms, and phrases still used around bread today.

Inclinations towards a communality of resources were codified not only into cultural and religious practices, but also in the hammulah systems used in the region pre-Ottoman occupation. Also known as the masha’a system, communally owned lands were shared and rotated amongst the villagers every few years, so that everyone could try their hand at different areas of the villages’ land, each with its own variables, creating a sort of equanimity within local society.7 A society that was built on and around mutual ownership and communality without exploiting one another, the resources, or the land itself, was done away with initially by the Ottomans with the introduction of public laws in 1858, later by the British, then by zionists.8 The commons continues to be erased by US-funded Imperialism, the true enemy of any life-giving system that offers an alternative to capitalist rape and exploitation of land, labor, and resources for the profit of few, and the oppression of many.

Tawfiq Canaan“The fellaheen to the south of Bethlehem told me the following story. Fätmeh, the daughter of the Prophet, once begged her neighbor to allow her to bake her bread in her tabun. The tabun was hot and ready for use, and the neighbor did not need it at the moment. The neighbor answered, “It is not heated and cannot be used.” The Almighty punished the woman who told a lie to justify her refusal to help her neighbor prepare bread, the holiest gift of God. She was turned into a tortoise. As a continuous reminder of her grave transgression against the heavenly rule never to withhold any thing which is needed for the preparation of ès (bread = life) she wore the täbún continually as a shell on her back.”

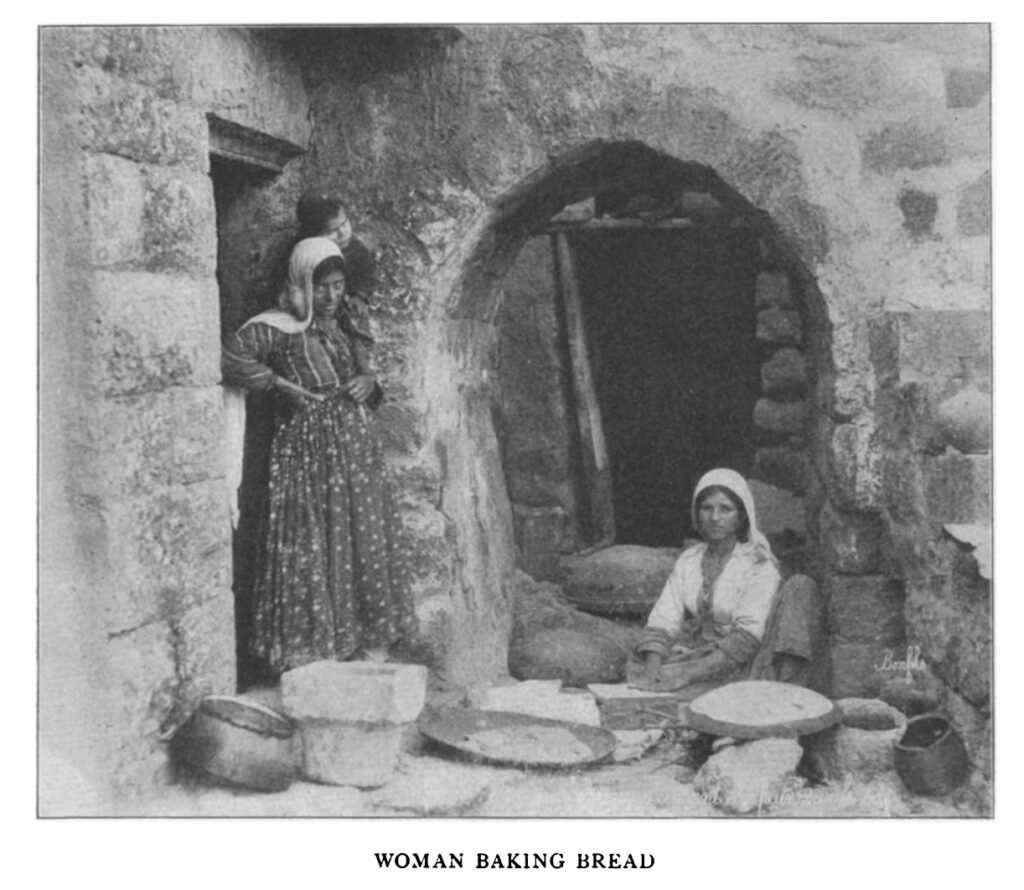

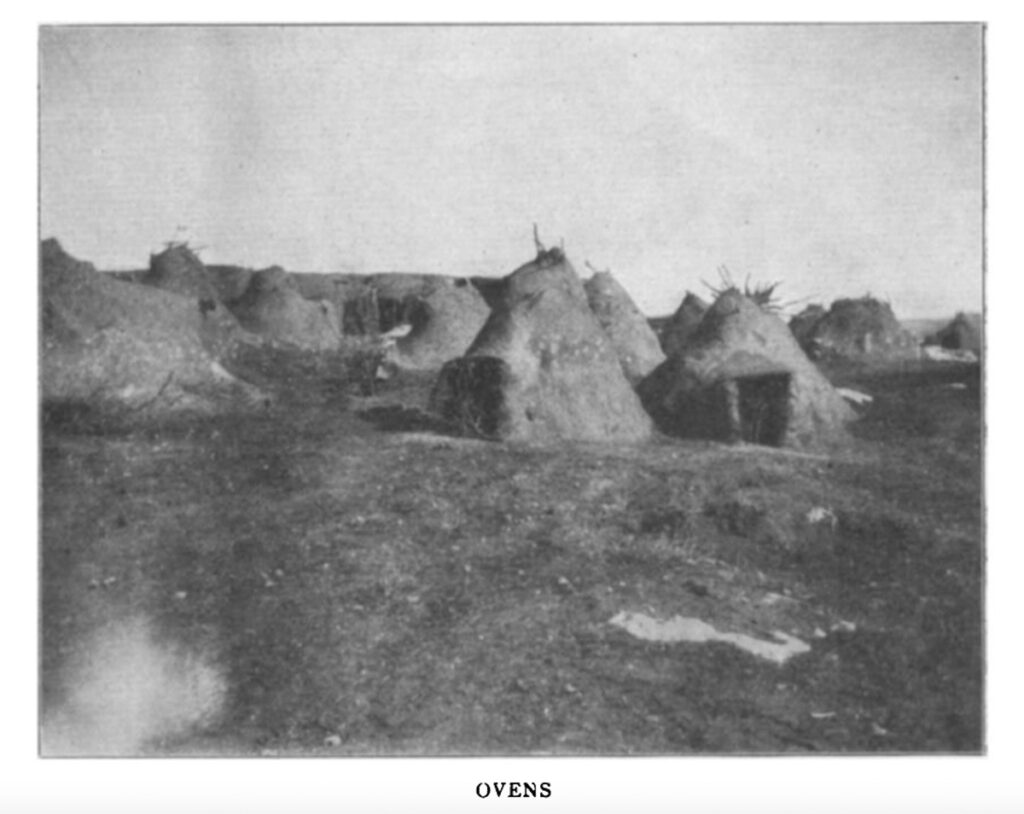

The tabun is a microcosmic manifestation of these larger structures of communality. Typically a dome-shaped oven made of unfired clay, the bottom of the tabun is lined with stones called radaf, and a small door seals the opening to keep heat inside not only for baking bread, but also for cooking. Less than three generations ago, communal ovens were a fixture in every village, serving not only as a resource from which people could feed their families, but also as a meeting place for women to share news/gossip, matchmake, tell jokes, and sing traditional songs. So much of our life in the not so distant past was communal, so much of our society and culture is built upon these ideas of community and care.

The two main ways of preparing bread historically in Palestine, both still used in some capacity to this day, are the clay tabun oven and the convex metal saj. Throughout contemporary Palestine, there are bakeries that use modern machinery and imported wheat to serve the needs of a large population whose diet centers around bread at every meal. The traditional saj and tabun, while less efficient at meeting those needs, are still very much in use. As one walks down main market streets of cities, it is a common sight to see a young baker flipping impossibly thin dough off of pillow forms and onto the dome of the hot saj. There are now machines that replicate the bubbly indentations of the tabun, like a bread printer. In some villages, women still bake in the traditional ways for their families, while others have harnessed the power of social media to create attractions out of ovens and culinary experiences for those who see our traditional cultural practices as novelty or tourism. In my village, there is only one woman baking bread in the somewhat traditional ways; her teenage sons kick around outside with his friends, as she pulls fresh rounds of flatbread out of her modernized version of a tabun, the wall behind her tagged with the words “Just Do It.”

Palestinian lyrics sung during the baking of bread and preparation of food in a tabun:

“ غني يا زهر الدحنونوارقص يا خبز الطابونطاح الشومر والزعتروودعنا سقعة كانون “

“Sing wildflower, dance bread of the tabun, fennel and thyme have grown, we have left the December cold”

In the post-1967 Palestine of my teta Subha, daily chores involved walking the hills to the spring and carrying water back for her family, a common task in every household until most springs were put behind walls, dried up, or poisoned by the zionist regime. My other teta Jamila used her tabun in that now crumbling stone barn behind the single room home, where she raised nine children, to bake the bread that she would take to Jerusalem. There she would sit along the wall under the majestic Damascus Gate to the Old City and sell her fresh bread along with balady eggs, foraged herbs, and fruits she gathered as the seasons provided. Two generations later, I am forbidden to visit this same place without a special permit. I have a green ID that only allows me to travel within the illegally militarily occupied-by-”Israel” West Bank regardless of my American passport. Because of these and other restrictions: checkpoints, the Segregation wall, loss of land, the ID system, and more, there are now far fewer of these traditional women selling their fresh breads and other products along the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Frantz Fanon“For a colonized people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.”

The explicit implications that accelerated settler colonial cultural and dietary redesign has had on the Palestinian population, when viewed from the standpoint of nutrition, genetics, and public health data regarding chronic illness amongst the people, is easily tied to the forced degradation of land relationships that previously had supported proper nutrition acquired through traditional diets. Studies of ‘ancient grains’ have shown them to be more nutrient dense and higher in protein than the wheat that is now grown in other places and imported to provide for the populations in Gaza and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Bread itself has changed significantly in Palestine over these last 80 years, due to these same human-made conditions. Today, 75% of the flour consumed in Gaza is heavily processed white pastry flour imported through the UNRWA, grown in places like Ukraine, hardly resembling the wheat native to the region. Scientific analysis has shown that the more highly refined a flour is, the lower the mineral content, on top of the already degraded (in comparison to older genotypes) mineral rates of hybrid varieties.9 The pita or kmaj bread that is most commonly consumed in Palestine now is very different in appearance, texture, and nutritional composition than the breads being consumed only three generations ago. Emmer grains have been shown to have the highest concentrations of protein, zinc, potassium, and calcium, amongst other minerals, compared with other wheats used for flour today.

The dissolution of pre-Ottoman communal land care systems, and the subsequent overdevelopment and land-based violence of settler colonialism, has caused ecological devastation that today sees increased wildfires, species extinction, and depletion of the water table. These conditions have nearly entirely eradicated traditional Palestinian agricultural economies. The knowledge and traditions that once defined Palestinian agricultural practices and dietary identity and kept the population in good health and symbiosis with the landscape have been decimated. Dependence on foreign aid for food, and pharmaceuticals produced by “Israel” to manage the health conditions that spawn from this dysbiosis, are corollary pillars in the degradation of food sovereignty that previously exemplified the Palestinian way of life.

In other ways, the impulse to live life communally is still reflected in aspects of modern Palestinian society, though as settler colonialism continues to wound the land and the people, capitalism infects and amplifies the primal need for survival and acquiescence to a system that doesn’t allow space for much else. As our families were forced to transition from growing the majority of their own food to importing it, Palestinians have become the third largest export market for “Israeli” goods. Namely agricultural produce, which is inherently less expensive than domestic alternatives produced by the remaining fellaheen. The “Israeli” government ensures this by providing “Israeli” farmers with free land and water, and subsidized insurance policies for their massive agricultural endeavors, protecting them from crop failure. Of course, there are no such insurances available for Palestinian farmers, who in addition to lacking access to these financial protections, face additional barriers to agricultural inputs. For example, in the case of irrigation, not only do they have to pay for water–they are also forbidden from capturing rainwater.10

Tawfiq Canaan“Partaking of food means making a covenant. The host as well as the guest may remind each other bênna ‘ês u-milk, “there is between us (the covenant) of salt and bread.” To say of a person that he knows not the significance of the “bread and salt covenant” is to stigmatize him as a bad person… Thus the expression “there is bread and salt between us;’ which has been used since biblical times, is equal to saying: “We are bound together by a formal covenant.” …A proverb says “only a bastard will betray (the covenant of) bread and salt” (ma bihún el-és wil-milh illà ibn el-harâm). Should a visitor partake of the food of a host he at once enters into the sacred covenant and can no longer take any measures against the host.”

Bread is sacred, bread is holy, bread is life. In Palestine, and in Islamic society in general, bread is treated with reverence. Bread that falls to touch the earth is kissed and touched to the forehead–another Earth–and a blessing is said. Stale bread is fed to animals, made into other dishes like fattoush, fetteh, or m’sakhan. It is not thrown away, ever. A daily scene I watch at home is my teta in her house gown, spreading stale bread, crumbs and other leftover grains out onto boards under trees and filling cook pots with fresh water for the neighborhood birds and cats—her daily task of feeding the other beings with that which must not be wasted.

Last time I was home, I coaxed a sourdough starter out of the thick air beneath the fig tree I’ve loved so dearly for all my years upon this Earth, diligently feeding the starter after its initial explosion onto the soft stone of our patio. My teta was left to lament and try to understand the new daily problem I had created for her: How to properly and respectfully dispose of the sacred primordial bread goo I was producing each morning with my starter discard? I had added to the chaos of my beloved matriarchs’ kitchen, already overrun by an endless collection of tea and coffee cups left behind by untold visitors that drop by day and night, in a culture that revolves around community and hospitality. The day I finally tested some flatbreads for my sido, I heard a yell from the living room (not an uncommon sound), that it was the best bread he had ever tasted. A high compliment from a man I jokingly refer to as ‘the President of the Kitchen,’ whose only culinary credential is being well fed by the women in our family.

Now, here, in a 100-year-old adobe dwelling in Taos, the land of the Pueblo people for at least as long as my people have been developing in the Levant, I’ve been resuscitating the desiccated starter of the locally milled grains that the fig tree impregnated. I carried it back across three borders and on many airplanes, though I have yet to venture to bake with it. The frequently cold temperatures and high altitude do not seem to have it feeling very active, and I can not only relate, but understand more about how beings do or do not evolve when dislocated. When I go back home again, I will dry some of this starter to take with me. I’ll repeat the process of reviving the starter, feeding it back to strength and vitality with the flour and the ancient microbial beings in the air of our land, just as I do with my own human fermentation, moving back and forth between home and diaspora.

Gustav Dalman

“In a destroyed city the voice of the hand-mill (jarusha) has become silent, as also the voice of the bride and the bridegroom… To take from a man his mill, or even one of his millstones, was to rob him of his daily bread; and a millstone would have been a good pledge, because its owner had to do his utmost to win it back. But the deuteronomic law (Deut. 24:6) forbids the taking of millstones, as the life of a man is not to be put in pledge.”

Wadi Gaza, or the Gaza Valley, is known for its waters. They run from the mountains in occupied Palestine, to their final destination in the Mediterranean sea. Gaza city was settled at least 5,000 years ago, making it one of the world’s oldest cities. In the last three months of the year 2023 AD, “Israeli” aerial bombardment of the 40 km by 8 km strip of land widely destroyed not only this ancient city and the cultural and architectural icons it held, but also the majority of infrastructure of the rest of the cities, villages and towns of the Strip. As of this writing, over 30,000 civilians have been murdered; directly in daily airstrikes using state of the art weapons deployed with genocidal intent on a captive civilian population with no military of its own, or indirectly by this system designed by the “Israeli” government to restrict medical care, sanitation, running water, food, potable water, medicine, and other critical life-supporting resources. Far more than those 30,000 martyrs are still lost under the rubble, missing, or injured.

In December 2023, it was reported by the World Food Programme that 9/10 Gazans were unable to eat every day and were skipping meals for extended periods of time, while most do not have daily access to clean drinking water. The vast majority of Gazan humans and animals are at the precipice of starvation and thirst, irrespective of gender, class, or education. This violence has seen 85% of the population internally displaced due to the “Israeli” governments’ unrelenting bombing campaign that has been targeting all aspects of Palestinian life there. The people have been without cooking fuel, electricity, or even kitchens, which has spawned a renaissance wherein mutual aid initiatives have led to the construction and distribution of tabun so that families are able to cook and bake whenever they are lucky enough to have access to basic ingredients like flour or water.

This most recent “Israeli” campaign against Gazan civilians has included the systematic targeting and destruction of all of Gaza’s bakeries, mills, farmland, and the UNRWA food storage facilities that provide 2 out of every 3 bags of flour. This now eradicated bread infrastructure was the backbone of sustenance and life for the 2.2 million people who have lived under a siege and blockade by “Israel” for almost 2 decades. In the early days of this assault, when some of the bakeries were still functioning in any capacity, thousands crowded into hours-long breadlines, with most leaving empty handed, and some never leaving at all. We have since witnessed human beings scrambling to locate flour, literally and physically. Videos of neighborhoods reduced to chaos show children scraping loose flour off of asphalt streets already covered in chemical weapons residue, waste, rubble, remnants of corpses, blood, and untold filth. Many reports from Gazans have shown people making a dystopian facsimile of bread–using a flour made from animal feed–especially in the areas where “Israelis” have prevented aid from reaching at all. Now, even if one does have flour, and clean water to make dough, the search for material to fuel a cooking fire presents a new problem. Every quest for a basic resource presents mortal danger from incessant “Israeli” aerial bombing, quad-copter drones, tank shelling, and snipers, as well as the expenditure of human energy already in critically short supply due to starvation, exhaustion, and frequent illness. Many Gazans have resorted to burning solid waste or cutting down sacred olive trees, as typical fuel sources have become unavailable.

Ghassan Kanafani“They steal your bread, then give you a crumb of it… Then they demand you to thank them for their generosity… O their audacity!”

Prior to this siege on the people of Gaza, 80% of the population was already food insecure. The “starvation diet” forced upon Gazans by the “Israeli” government has been well publicized. During status quo times of siege, 500 trucks a day entered the Strip to supplement the needs of the people living there, but even those trucks were heavily restricted and scrutinized. Chocolate, amongst many other things, has long been banned from consideration as “permissible cargo.” Since this assault on Gaza began in October, far less than the daily minimum of food, water, and medical supplies needed have been allowed to enter an area where millions of people are being intentionally starved to death. Historical precedent delineates that the intentional destruction of the Gaza strip and the systematic starvation of its civilian population clearly demarcate a genocide, one of the worst human-made atrocities of our time. It is important to note that these conditions are a result of deliberate decisions, made by individuals in positions of great power, with the near total support of their constituents and populations. These facts should make all conscious human beings take pause and consider their place and participation in the times we live in.

The situation recalls the 2.5 year siege of Leningrad by the Nazis and their collaborators, wherein starvation was explicitly used as a methodology for the murder of 1.5 million civilians, beginning in September 1941. For six months, the only food available to the average Russian citizen was approximately 125 g of bread per day, over 50% of which was a mixture of sawdust and other inedibles.11 This blemish on recent human history has long been acknowledged as one of the most horrific crimes against humanity allowed to transpire during WW2, thought only to have been made possible because citizens of the world were not privy to the conditions and reality of human-caused suffering. We are ever hopeful as a species, to assume that the barbarism of starvation would have been left in the streets of Leningrad, over eight decades ago, never to be manifested again with such explicit desire for the death of other living things. Today, the tragic reality of our time is that the intentionally created horrors of now are perhaps worse than the horrors of then for their visibility and avoidability, ever present in the form of live streams in real time, on demand on the cursed devices we live our modern lives attached to. All made worse by the deafening silence and purchased impotence of global governments and their disenfranchised masses, threatening an almost certain potential for future violence elsewhere, against anyone.

The “Israeli” entity, as the occupying power in Gaza and all of Palestine, is bound to abide by International Humanitarian Law, which not only strictly prohibits the use of starvation as a method of warfare, but obligates it to appropriately provide for the needs and protection of the population which it occupies.12 In 2018, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 2417, which declared the use of starvation against civilians as a weapon of war and any denial of humanitarian access a violation of international law. Our relatives in Gaza have experienced a hyper-synthesized version of the worst that humankind has to offer, coupled with the decades of ongoing dehumanization of millions of us fueled by ignorance, racism, indifference, and the ethno-supremacist ideology of zionism. This is the impunity of the oppressor that they, and we, the oppressed, have become accustomed to. A most modern collusion in service of most archaic ends.

The Land of the Seventy Wonders

Grief is jasmin

In the land of the seventy wonders

And poverty is music

And the death of God in an ambush

Is bread,

And the learned professor of languages

Jurisprudence and medicine

Is Juha’s ass—And grief is jasmin

Sameeh Al-QassemIn the land of seventy wonders!

These days, images of freshly baked pita bread scattered in the streets amongst the limbs of those who had waited in lines amongst hundreds of their fellow citizens, where dust and rubble co-mingle with blood and fragments of flesh, are just some sordid examples of how the pixels on our personal portals into atrocity have arranged themselves. These are coupled with horror stories that seem so impossible that they have taken on a folkloric form reminiscent of the grimmest of folk tales. Yet these stories are firsthand accounts given by survivors, witnesses, and victims, and they come not only as words of mouth but as photographs, videos, and livestreams of the scenarios themselves. To deny them is to deny everything true and real about the duality of life and death.

Food has been wielded as a weapon since the dawn of civilizations. Only the application, location, and ingredients of the recipe have changed. It has proven to be one of the most effective tools against entire cities and populations of those who are deemed ‘enemy’. Throughout history, many horrors have been linked to wheat and bread, specifically. Massacres happen because of it, and famines because it isn’t.13 A most malleable medium, made more effective by bread’s importance in so many human cultures. Life or death waits for whichever population is given access to or deprived of it. Bread is a weapon, the staff of life and the staff of death. Wheat is the sower and the reaper, that which sustains life, or the scythe that takes it. So much opportunity for spiritual evolution for humankind is lost in the inability to recognize that as we do to other beings—humans, plants, animals, the earth—we do to ourselves.

Bread is a weapon, the staff of life and the staff of death. Wheat is the sower and the reaper, that which sustains life, or the scythe that takes it.

And so, there is precedent for the horrors made by man in 2023, that have continued into 2024, though the nature of them seems as barbaric as that which we associate with medieval periods. Bread, a most primeval and pedantic metaphor, wielded against the innocent, is almost comical in its barbarism, yet somehow we believe we are different. Many believe that our times are no longer those of famine, disease, disaster, illiteracy—the colonial markers of a society not sophisticated enough to survive. So many of the horrors that we have seen and heard from Gaza in recent months are tied to bread. Many fathers, sons, pregnant widows, were bombed in broad daylight clamoring for a bundle of pita, thousands of people waiting in lines for hours, in the hopes of getting a few pieces to feed their families. Images of sacks of fresh bread that should be dipped in precious olive oil and za’atar, instead soaked in the blood of someone recently dispossessed of life, later to see the same sacks repurposed by fathers to carry the charred and amoebic fragments of their own children, for whom they used to go and get bread. Children and babies are starving, and the world watching still has its’ daily bread.

DEFIANCE

You may fasten my chains

Deprive me of my books and tobacco

You may fill my mouth with earth

Poetry will feed my heart, like blood

It is salt to the bread

And liquid to the eye

I will write it with nails, eye sockets and daggers

I will recite it in my prison cell—

In the bathroom—

In the stable—

Under the whip—

Under the chains—

In spite of my handcuffs

I have a million nightingales

On the branches of my heart

Mahmoud DarwishSinging the song of liberation.

In August 2022, when a young resistance fighter by the name of Ibrahim Al-Nabulsi was assassinated by the “Israeli” military in the old city of Nablus in the North of the West Bank on a weekday morning, I watched with horror, first on my phone screen, and later on television with my grandparents. A few days later I found myself, by chance, visiting the destroyed stone house where his still sticky blood was collecting the dust of the rubble left by a missile sent to kill from close range, which also destroyed the neighbor’s kitchen wall that it was launched through, as the family that lived there was held blindfolded at gunpoint. On another wall there still hung a plastic bag that held bread next to an old frying pan, and on the ground, his tactical vest and a prayer mat. Today in Gaza, the path of the martyrs comes without even this, our daily bread.

The deprivation of a people whose blood soaks into the same earth it has for thousands of years, the same earth from which our ancestors developed a wild grass into wheat for the whole world to eat, is perhaps one of the most simultaneously obvious and subtly poetic ironies. The depths of violences being committed to the people of Gaza are perpetrated not only by “Israel,” but an entire world that has built its societies and governments on the fruits of our ancestral labor and stewardship. Bread is being used as a weapon by usurpers to wield death against millions of the descendants of those who co-evolved and created life. Genocide and ethnic cleansing is a strange punishment for a peoples’ commitment to steadfast presence on their own land. Palestinians are an affront to the systems destined to crumble under the weight of crimes against life on this planet.

From the international community we demand far more than just our daily bread: we demand more than condemnation and empty gestures. We demand a full stoppage to life as usual, to refuse to set a precedent of complacency and collusion in war crimes and genocide, for our people, or for any people. We demand a world wherein our fellow citizens refuse to passively or actively co-create a society that deems anyone more worthy of life and rights than others. We demand recognition of our dignity, of our rights, the return of our lands to the people, and the people to the lands, and the solidarity of our fellow human beings NOW, 76 years of catastrophe is enough. We demand action, resistance, and change. The time is now. Between us is only bread, and salt, after all.

Affirmation

I believe in living.

I believe in the spectrum

of Beta days and Gamma people.

I believe in sunshine.

In windmills and waterfalls,

tricycles and rocking chairs.

And i believe that seeds grow into sprouts.

And sprouts grow into trees.

I believe in the magic of the hands.

And in the wisdom of the eyes.

I believe in rain and tears.

And in the blood of infinity.

I believe in life.

And i have seen the death parade

march through the torso of the earth,

sculpting mud bodies in its path.

I have seen the destruction of the daylight,

and seen bloodthirsty maggots

prayed to and saluted.

I have seen the kind become the blind

and the blind become the bind

in one easy lesson.

I have walked on cut glass.

I have eaten crow and blunder bread

and breathed the stench of indifference.

I have been locked by the lawless.

Handcuffed by the haters.

Gagged by the greedy.

And, if i know any thing at all,

it’s that a wall is just a wall

and nothing more at all.

It can be broken down.

I believe in living.

I believe in birth.

I believe in the sweat of love

and in the fire of truth.

And i believe that a lost ship,

steered by tired, seasick sailors,

can still be guided home

Assata Shakurto port.

This essay was originally commissioned as part of the exhibition Cum Panis: Bread and its Ecologies curated by Adeline Lépine and Grace Gloria Denis, currently on view at Le 19 Crac, Montbéliard, France.