Stir-fry Basil Snails are a staple item on the menu of Taiwanese rechao restaurants, casual late-night eateries characterized by abundant wok-fried dishes served rapidly, often across low tables and plastic stools. Reflecting upon the cultural significance of rechao establishments, Taiwanese-American journalist and writer Clarissa Wei emphasizes how the very menu tells a “cohesive story of what it means to be Taiwanese, an identity that is multicultural and nuanced”. This snail dish is a perfect example, as the star ingredient is commonly cooked with Giant African Land Snails (Achatina fulica), an invasive species introduced into Taiwan in the 1930s during Japanese colonial rule (1894-1945) by Shimojō Kumaichi, a Japanese public health administrator, who sought to breed the snail for food and economic gains.

Taiwanese-Paiwan artist En-Man Chang spent years exploring the migration route of the Giant African Land Snails and its ultimate culinary incorporation in Taiwanese cuisine to examine Indigenous narratives in shifting socio-political terrains. Chang focuses on the cinavu recipe, a Indigenous Paiwan delicacy eaten at celebrations that wraps the snail in shell flower leaf, along with millet and pork. Working across performance, photography, video, installation and community-focused projects, her multidisciplinary practice expands upon her own heritage as an Indigenous person, and continues to contribute to an evolving understanding of a quintessential Taiwanese expression and experience.

In conversation with Chang, we spoke about retracing Taiwan’s colonial history through an Indigenous culinary perspective, her changing views on the snail as an invasive species, recipe adaptations for workshops held outside of Taiwan, and her recent experiences in Nigeria, the closest she’s been to the native home of the Giant African Snail.

This interview has been translated from Mandarin Chinese to English, and edited for length and clarity.

Annette An-Jen Liu:

Since 2009, your practice has centered around the Giant African Land Snail as a way to explore and communicate Taiwan’s Indigenous history. What kept you coming back to this subject? What inspired your commitment to it?

自2009年以來,您的創作與研究一直圍繞著非洲大蝸牛,以探索並傳達台灣原住民歷史。是什麼讓您一直回到這個主題?是什麼激發了您的長期的投入?

En-Man Chang:

The theme of the Giant African Snail was actually interrupted from 2013 until 2019, when I had an opportunity to participate in the Singapore Biennale, which reignited my exploration and enabled me to delve further into the subject.

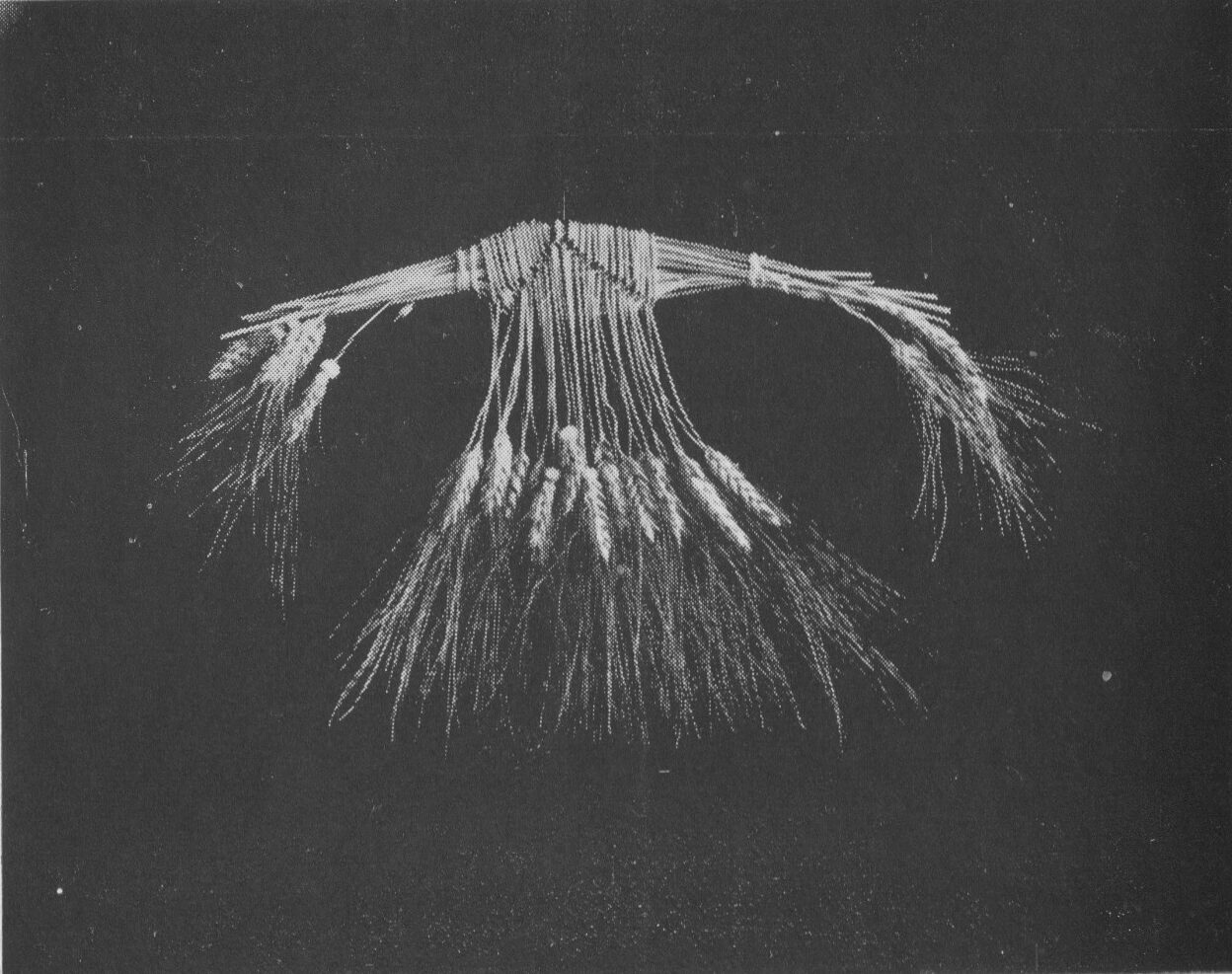

My initial engagement with the topic began playfully, with Snail Playground (2009), where I attached miniature Taiwanese architecture models onto snail shells and let the snails roam over a mound of soil in the shape of Taiwan, carrying these buildings. The following year, I staged a performance titled Fresh Snail (2010), mimicking my Paiwanese mother preparing snails [to eat]. A three-channel video piece titled Snail Dishes Interview Program: Highway No. 9 (2013) followed, where I interviewed locals from the Kanadun, Tjuaqau, and Pacavalj communities in my mother’s hometown and filmed them demonstrating how to cook snails. This completed my regional exploration but then I grew stagnant.

I’m fascinated by how non-native species have triggered certain cultural transformations locally, and I’m beginning to wonder how people in other regions perceive or deal with the introduced/invasive external entities.

The opportunity to go to Singapore was exciting because the Giant African Snail was actually introduced into Taiwan via Singapore in 1933, when Taiwan was still under Japanese colonial rule. I found many historical materials at the National Library of Singapore, including a map depicting the spread of these snails over time, which prompted a wider imagination across time and space, leading me to expand [my practice] further out into the world.

一開始有些戲謔的將建物模型黏在蝸牛殼上讓牠背著行走(蝸牛樂園2009);爾後回到模仿排灣族母親處理蝸牛肉(現打蝸牛2010);在母親的原鄉尋找族人們演繹蝸牛料理(蝸牛料理訪談計畫-台九線篇2013),完成地區性探究便停滯了。

其實「非洲大蝸牛」這個主題曾在2013年中斷,直到參與2019年新加坡雙年展的契機,再重拾蝸牛並進一步檢視牠。在選擇一個物種作為主要的凝視對象,多少也爬梳了牠的背景,有機會前往新加坡那是令人興奮的,因為蝸牛正是1933年從新加坡引進當時還是日本殖民統治的台灣。在新加坡國家圖書館找到許多相關史料,其中一張蝸牛傳播時間路徑的製圖,觸發我橫越時空的想像,像是引領我向世界擴張。

AL:

You’ve mentioned that your snail series may be “reinterpreted as a strategy for resisting colonization,” while illustrating an “evolution of interactions between human, animal, and environment.” It seems that this process of resistance also entailed adaptability, accommodation, and an embrace of inevitable change. How has your view on the Giant African Land Snail as an invasive species changed over the years?

您提到過,您的蝸牛系列可能被「重新解釋為對抗殖民的策略」,同時描繪了「人類、動物和環境之間互動的演變」。這個反抗過程似乎還包括一種適應性、遷就性,以及對不可避免變化的接受。多年來,您對非洲大蝸牛這類入侵物種的看法,有何變化?

EC:

There have definitely been new realizations at each stage, whether or not the snails were deliberately brought over, or inadvertently came with cargo ships, the snail left its native East Africa and embarked on a maritime adventure of its own. To me, the map of the snail’s dispersal and migration resembled the routes of colonial expansion, and the trail of mucus left behind by the snail suddenly seemed like lingering traces of colonial ghosts… [but] these associations are my interpretations. From frequently encountering the unassuming mollusks on roadsides on rainy days, to noticing them from my mother’s cooking, then incorporating them into my creative practice and having it speak to my engagement and focus on Taiwanese Indigenous issues, I’ve found that there have been new realizations at each stage.

不論是否為人為的攜帶,或是不經意間隨著貨輪進入洋流,蝸牛離開了牠的原生地東非,展開了屬於牠的大航海冒險;看著那張蝸牛散播圖,恰似帝國擴張的路線圖,而蝸牛行走留下的黏液,猶如殖民幽靈的痕跡,這段是我的聯想釋義。從雨天經常看到在路邊淺草泥地習以為常的爬行物,到關注牠是從母親的料理開始,進入創作主題則與我接觸與關心台灣原住民族議題相呼應,不同的階段會有一些新的啟發。

AL:

I think the Giant African Land Snail is a good example of how invasive species thrive in the parts of the world they’re introduced in and challenge our concept of “nativeness,” despite the vigor with which they populate and ultimately often integrate into their newfound environment. How do you consider this paradox in your practice? Specifically with the way Paiwan people incorporated this invasive species into traditionally important recipes such as the cinavu, to be served at festivals and weddings?

我認為非洲大蝸牛是入侵物種在引入的新環境中繁殖的一個很好例子,挑戰著我們對「本土性」概念的理解,儘管它們以活力充沛的方式在新環境中繁殖,最終通常融入其中。您在創作中如何思考這種矛盾性?特別是在排灣族人將這種入侵物種融入傳統重要的菜譜,成為在節日和婚禮宴席的cinavu大菜。

EC:

During the live performance of Fresh Snail (2010), my handling of snail mucus was clumsy—a humbling experience. It was only after [the work] that I learned about the paper mulberry leaves, a native species of Taiwan, which could easily remove snail slime.

In a pursuit of decolonization, there is something invigorating and inspiring about the native species “eliminating” the invasive one.

Snails are often regarded with disgust in the city, but are seen as a free, protein-rich ingredient in the resource-poor rural areas. Their incorporation into the precious traditional Paiwan food of cinavu may have something to do with the economic disadvantage [of rural communities], but I prefer to think of the wrapped cinavu snails as a form of cultural tolerance.

I’m fascinated by how non-native species have triggered certain cultural transformations locally, and I’m beginning to wonder how people in other regions perceive or deal with the introduced/invasive external entities.

在〈現打蝸牛〉臨場藝術(live art)裡笨拙處理蝸牛黏液的經驗,在得知台灣原生種構樹樹葉能輕易處理蝸牛的黏液,入侵物種被本土物種消彌,在追求解殖的路上這點真是振奮人心。通常在城市被嫌棄噁心的蝸牛,卻是資源匱乏偏鄉免費的蛋白質食材,會被納入珍貴的排灣族傳統食物cinavu或許與經濟弱勢有些許相關,但蝸牛被包進去cinavu裡,我寧願視它為一種文化包容,非本土物種也牽動了某些在地的文化轉化,這些想法讓我覺得有趣,我也開始好奇其他地區的人們如何看待或應對外來進入/侵入的人事物。

AL:

At your cinavu cooking workshop in New York last October, corn husks and epazote leaves substituted the jiasuanjiang and ginger shell leaves typically used. When an audience member commented that the ingredients needed to make cinavu could probably all be found in Chinatown, I recall you responding that you enjoyed the challenge of finding local replacements for the recipe. What informed your openness to experimenting with and adapting a culturally significant delicacy?

在去年十月的紐約cinavu烹飪工作坊中,玉米殼和epazote葉替代了通常使用的茭發薑殼葉。當一位觀眾表示意見說,製作cinavu所需的所有材料可能都能在紐約的唐人街找到時,我記得您回應說,您喜歡去挑戰尋找原本食譜的在地替代品。是什麼原因促使您願意嘗試和適應具有文化背景的美食?

EC:

When I conduct cinavu workshops outside of Taiwan, there are always practical considerations about not being able to bring fresh ingredients through customs. Apart from local Taiwanese millet, which is a transportable grain, other ingredients need to be substituted. Among these is the native plant khasya trichodesma (T. khasianum), an edible herb that is the star of the cinavu recipe. These plants not only contain alkaloids that can neutralize stomach acid, they also don’t tend to overcook. So finding a suitable substitute for them is challenging, but also the most interesting and rewarding.

In Singapore, I found the noni leaves, which carry several healing properties and are said to be associated with Samoan culture. In Kassel, I used large jars of pickled grape leaves sold in Turkish markets, reflecting on the demand for cheap labor in Germany in recent times and the subsequent influx of Turkish immigrants. This resonated with another series of mine on urban [Taiwanese] Indigenous peoples. The epazote leaves I used in New York were recommended by a Mexican friend, and their strong aroma was similar to T. khasianum. While at a friend’s house in Manhattan, I tried cooking with them and made a pot of Paiwan mountain vegetable rice.

在台灣島土以外的地區進行cinavu工作坊,有無法攜帶生鮮食材入關的現實考量,除了本土小米是可以運輸的穀物,其他材料則尋找替代食材。

其中民族植物假酸漿(Khasya Trichodesma)葉為cinavu的靈魂材料,含植物鹼有抑制胃酸的功效,是耐煮且可一起食用的包葉,尋找其替代品是具挑戰性的,也是最有趣也總有收穫的一環。

在新加坡找到了諾麗(noni)葉,帶有許多療效諾麗葉據說與薩摩亞(Samoan)文化有關。在卡塞爾找到的是土耳其超市販售的大罐醃漬的葡萄葉,反映了德國近代廉價勞動力需求而有著大批土耳其移民,與我另一個關於都市原住民的創作系列有既視感。在紐約尋找到的epazote葉,為墨西哥友人的推薦,強烈的香氣類似假酸漿葉,期間在曼哈頓朋友家使用它煮了一鍋排灣族的山地菜飯。

AL:

More recently, you visited Africa for the first time, and held your first cinavu cooking workshop in Lagos, Nigeria, as part of the touring group exhibition The Oceans and The Interpreters. What was that experience like? Were there any adaptations for the cinavu recipe? Did being in the continent—where the snails originated from, influence your relationship to the species, and by extension, to your work?

最近,您首次去了非洲,也在奈及利亞的拉各斯舉辦了第一次的cinavu烹飪工作坊。那次經歷是什麼樣的情況?cinavu的食譜有什麼變化,是以當地食材去代替的嗎?在非洲,也就是蝸牛的原產地,是否影響了您對這種物種的關係,進而影響了您的創作?

EC:

In Nigeria, which is close to the Giant African Snail’s native home [of East Africa], there are very different food habits [compared to Taiwan]. The three leaves that were recommended to me [to substitute the T. khasianum] were morning glory, tree spinach, and ogu, which the locals cut up, instead of using the leaves in its entirety. So for the workshop, I convinced everyone to experiment using the leaves differently with me. However, the cooked cinavu was judged to have no flavor, so the [local participants] insisted on making another batch with chopped leaves and spicy salty sauce to accompany it (laughs).

Nigeria is located in West Africa, which is still quite a distance away from the snails’ original home in East Africa, but the snails sold in the Nigerian market are also enormous! Being there fulfilled my dream of completing the trilogy Snail Paradise – Setting Sail or Final Chapter (2021), where people sing the tale of the African giant snail using ancient melodies, inspired by the Griot tradition of West Africa. It’s a tribute to a culture that is both unfamiliar and yet strangely similar.

It’s hard to say whether or not I’m wrapping up the snail series here, as I’ll perhaps come across new inspirations in the near future and embark on another chapter.

在離蝸牛原鄉最近的奈及利亞,有很不一樣的飲食習慣,被推薦的三款葉子morning glory 、tree spinach與ogu,當地人們習慣切碎使用,在工作坊則說服大家進行一場實驗,煮完的cinavu被評沒有味道,堅持要另外做碎葉加辛辣鹹醬來搭配(笑)。奈及利亞位於西非,距離蝸牛原鄉東非還是有相當大的距離,市場販售的蝸牛也很巨大,也是完成了我一個想望,圓滿了《蝸牛樂園三部曲-啟航或終章》(2021)裡,族人用古調吟唱非洲大蝸牛的故事,也是仿效西非的吟遊史官Griot,是對陌生又相似的文化的致敬。不敢說我是否就此終結蝸牛系列,或許不久的將來,我又有新的啟發與篇章。

En-Man Chang

Born in Taitung, Taiwanese artist En-Man Chang currently works and lives in Taipei. Utilizing the forms of the moving image, photography, installation, and creative forms of self-organizing and collective projects, Chang’s practice explores how the indigenous people of Taiwan negotiates the ever-shifting socio-cultural terrains and conditions for survival in contemporary Taiwan against the backdrop of modernisation and urbanization. Chang excavates lost histories and narratives to explore the world at large, aiming to embody the transformative potential that art holds.

Chang has had solo exhibitions in Taipei (2012), Vancouver (2016), Los Angeles (2017); ; and exhibited in major projects such as the Taipei Biennial (2014), Taiwan Biennial (2018), Istanbul Biennial (2019), Cosmopolis #2, Centre Pompidou (2019), Singapore Biennale (2019), Kathmandu Triennale (2022), and documenta 15 (2022). Her works have most recently been included in group exhibitions in New York City (Singing in Unison Part 8: Between Waves, 2023) and Lagos (The Oceans and The Interpreters, 2024), and is currently on view as part of Sea Monsters, Artillery Fire, and Them: 400 Years of Fort Zeelandia in Tainan.