When Allan Wexler is confronted with the awkward question, “What kind of work do you do?” he hands out a printed business card that reads:

“I am an architect in an artist’s body. My studio is a laboratory. I sculpt with gravity and paint with rain. The work looks at simple things: the sight lines between seated people, the way that two bricks intersect, the line between inside and outside. I invent ways to walk through walls. I build anti-gravity machines.”

Trained as an architect, Wexler is a fine artist that toys with the thinking and motifs in design. In all of his work, the purpose is meant to elucidate a simple idea or theme about making, living, or living together. A humble, yet totemic figure, his influence is strongly felt throughout contemporary interdisciplinary practices. He is a model for how to work, how to act, and for thinking about the future.

I first wrote about Allan’s work in 2009 as part of Lawrence Blough’s Pratt seminar “Genealogies of Architectural Program.” What initially drew me to the work was its immediacy. It is grounded—its messages are clear and rooted in imagery that everyone has experience with—chairs, tables, garden sheds, cutlery. It is unpretentious, powerful, conceptually accessible, and democratic.

After graduating, his work came up again as a topic of conversation between Jean Lee and Dylan Davis (of Ladies & Gentlemen Studio) and myself where we all discussed his impact on our way of viewing design. We reached out to Allan and he immediately asked us over to dinner at his home. After this moment, we became good friends and frequent creative collaborators. One might even say our friendship was founded around food.

Although his work is much more diverse than the projects focused on in this interview, Allan’s work around dining is particularly interesting. Dining is a rich cultural touchstone that we all experience everyday. At its essence, it is serving a functional need to survive and yet can be filled with a deeply individualized experience, emotion, and meaning. In the conversation below, I speak with Allan about how food and dining are a medium and a means to a conversation about what connects us.

Michael Yarinsky:

Could you describe your practice?

Allan Wexler:

My practice is a cross between fine and applied art. I’m trained as an architect, but have always been interested in the speculative aspects of architecture. Architecture is a material I work with, but it’s not the result. [The work] ends up being art that’s about the content of architecture and design.

MY:

What’s it about the theme of dining that keeps you returning to that subject?

AW:

For me architecture is about eating, sleeping, and bathing—so dining was one of the topics that I was always most drawn to. To step back, I first started making chairs—which became a kind of stand-in for buildings—because they could become a fractal that could grow into the idea of architecture but allowed me to build them myself. I could be more experimental and loose-minded. Also, chairs are easy to draw, and I wasn’t very good at drawing, But the chair only existed for me formally or sculpturally as material at first. Over time I discovered function, human function.

MY:

The work you do around dining has a lot of scales and takes a lot of forms. The “Braun Aromaster 10 cup coffee maker” (1991) is a pretty clear allusion to a ritual act and tea ceremony.

AW:

Really looking at the minutiae of life and each frame of movement, like in a slow motion film where you can almost see each frame segmented with the black space in between, I was trying to look more closely at the most uninteresting, insignificant details in my own life. Making coffee in the morning becomes so rote and so everyday, but how do you then reinvent it.

I did a series of transformations of the Braun coffee maker designed by Dieter Rams—it was ubiquitous. I started decomposing it, taking it apart. In that piece, I just took all of the parts that were already manufactured. I disassembled it and made a kit that expressed and showed each element, whether it was a screw or a wire or a coil or a copper pipe or a plastic piece of bushing or washer, and I exhibited them in a carrying case, as if they were ancient relics. I include a screwdriver and plier, implying that you would actually reconstruct the coffee pot every morning to make a cup of coffee.

MY:

A piece like “One Table Worn by One Person” (1989), starts to shift scale and, in my mind, is a lot more about the people involved than the object itself. In this piece, there’s a host that wears a table and a guest that is served. What’s it about the relationship between people you’re trying to explore?

AW:

I think it also references the tea ceremony, in which the tea master spends enormous effort to prepare tea for his guests, and yet doesn’t necessarily partake of the tea, so it’s being a good host. There’s a burden. You’re cantilevering a table, and you’re wearing it for the sake of having a nice meal for your guest.

It’s also my interest in the extension of the body into space, the relationship of clothing to architecture and furniture, how when we sit at a table and place our hands on the table, our body merges with that table, conceptually or spiritually, so I’m actually physicalizing that kind of spiritual idea of using a table as a bridge and a connector across and between people. One person is sitting at the table on one side, one is on the other side, and the table either connects or separates.

Allan Wexler“Just do it…Do what feels right. You do it because it’s comforting. It reminds you of your childhood. You use that material because you love the smell of it. That drives the intellect forward.”

MY:

The extension of a tool or a piece of design as an extension of the body is really interesting. The moment that the tool connects with the body and is then used as a challenge to the relationship between people I think is really important.

AW:

I like this idea of the tool. I think Marshall McLuhan describes the tool as an extension of the hand, but it’s also an extension of the mind. They’re also triggers, and they activate ideas. This kind of physical object can be a trigger to create emotion, spirituality or intellectual ideas, philosophical notions. I love that, in architecture and design, the physicality of materials can become transcendent and become other-worldly and create a sense of mystery and awe, which I don’t think a lot of designers talk about so much. I’m always bringing up issues of mystery and magic and mythology and invention.

MY:

Yes, also, your work challenges social norms. I think that it’s important, when looking into the future and what’s good and necessary about art or design (or applied art), that a lot of norms were there for reasons that don’t necessarily apply to us anymore. Now they’re just norms because they’re norms.

In a project like “Coffee Seeks its own Level”(1990), I believe you’re trying to create a more equal playing field. It’s not about the host and the guest anymore, it’s about creating a mutual understanding or even mutual aid to work together. Could you talk a little bit more about what you were aiming at?

AW:

It is about the possibility of what we could be. We could lift the cup before the others to try to get more coffee, but it has repercussions and spills out of the other coffee cups–in kind of an enforced democracy and equality among four people. It is about human interaction choreography, and it speaks of that level playing field that you’re talking about.

MY:

Going back to that idea of the ritual,“Body Language” (2009). In this project, I think you’re directly trying to create a record of events of a meal through the use of pencil points at the bottom of a chair.

AW:

That’s right.

MY:

Why is it so important to record a moment like that?

AW:

My interest is in the idea of patina and age. I said, “When you move a chair around the floor and it scratches the floor and you’re devastated.” I was asking, “What would happen if I actually had routers connected to the legs of chairs, and it started digging and carving grooves in the floor every time I moved my chair toward the table or away from the table during a conversation with two people?” You’d end up with this beautiful, sculptural, carved wooden floor. That became the idea for the pencil. It is marking, protecting, and preserving a moment in time, which will never happen again—trapping time… stopping time. I think that’s somehow what artists do. They stop time. I think it’s about mortality in a way. We protect and preserve those moments and record them, so it’s a way of recording a nonverbal conversation.

MY:

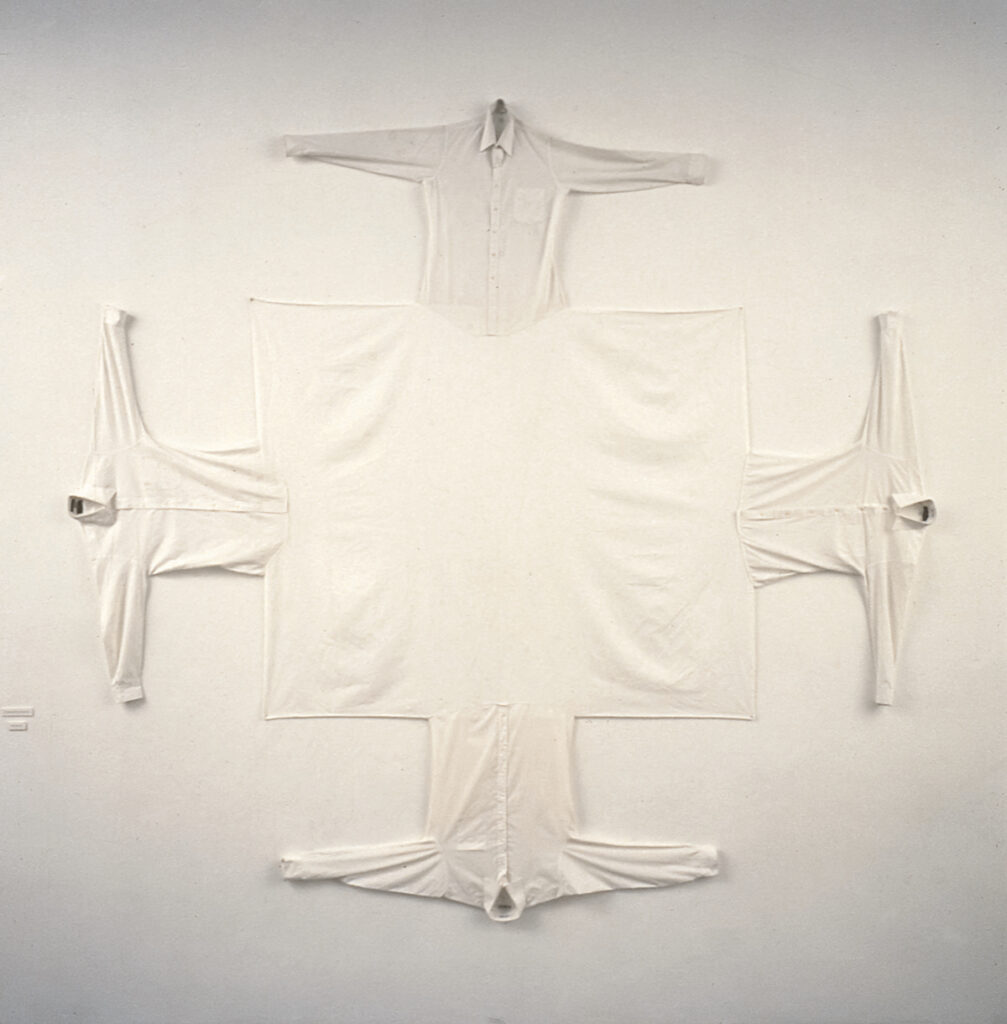

We’ve talked about slowness, ritual, honoring objects, communication between people and objects, collaboration between people, and the importance of recording a moment, I feel like one project that kind of hits on all of these things is “Four shirts sewn into a tablecloth” (1991). Can you talk more about that project?

AW:

I had always said that architecture is like clothing; it’s an extension of the skin. From a planar material like sheetrock and plywood the material starts to triangulate and pixelate around the curvature of the body—the next evolution is fabric—and so fabric became something that I became interested in. In this relationship between clothing and architecture, the white shirt is a symbol of a human. You’re sitting around a table, and the tablecloth is covering the wood. It’s a way of transforming a profane object into a sacred object. Then you extend it, and the tablecloth covers and wraps the body—so that you are interconnected to each other through the table surface itself.

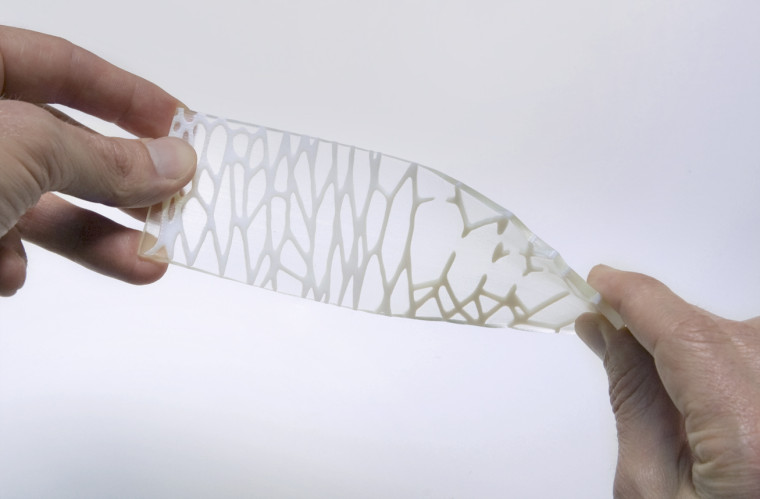

When I was in residence at a glassblowing facility, and I was making wearable glass vessels, I bought a sewing machine, and I learned how to sew. I was sewing all kinds of things that would allow me to retrofit glassware to my body, using fabrics.

I think I may be going back to my roots. My grandfather was a tailor. He always called fabric “yard goods”. He would take my clothing and pinch it and say, “Oh, this is a nice piece of ‘goods’.” I always loved that.

My grandmother was an excellent seamstress as well. I remember, my grandparents lived upstairs from us—She would pump the pedal of the sewing machine, and every year she would make me a denim work apron with all these pockets for all my tools because I loved making things as a child. Childhood memories, and how important they are to me. I think we all want to return to the comfort and warmth of growing up in a family.

MY:

What could be more interconnecting of you as a child to you in your future career than that?—an apron that is fabric, that is an extension of your skin, filled with the tools that are extensions of your body…

AW:

It’s so great. I should do a series of aprons.

MY:

Agreed.

You’ve worked very heavily in education since your early career. What makes you want to make teaching so core to your practice?

AW:

It is a major part of my practice. I always tell people that teaching is “social sculpture,” in the words of Joseph Beuys. I feel like I’m putting together a sculptural performance if I’m teaching, or if the curriculum is about invention and creativity, and I’m trying to push boundaries, maybe break the rules.

I’m pushing boundaries so that product design merges with fine art and fine art merges with product, and ambiguity can take place.

My background is architecture, in terms of education, but I prefer the loneliness of my studio. I tend to compromise too much if I’m collaborating with other people, so I chose not to follow a traditional architectural practice. I found that teaching allowed me to move out of the comfort and the privacy of my studio, into the world where I can actually have conversations with people. That’s kind of my alter ego. Teaching is a bit of a performance. It’s slightly theatrical, and I enjoy that.

MY:

I’ve been a guest critic on several product design juries of yours at Parsons. I know that food and cooking projects are core to that education. Specifically, the most recent one was a picnic basket. Could you just talk a little bit more about why food and dining is so core to your educational practice?

AW:

I think it started with basic necessities of life. I think that’s what product designers experiment with is to make the basic necessities into theatrical moments. For several years, I’ve done projects with students where I’ve asked them to do performances based on drinking a standard cup of water. Then, out of that, they construct drinking vessels that make people aware of the more specific personal aspect or experience. Water is a great source for many projects because water takes the form of whatever vessel it is in.

How do you hold the water? How do you transport it? How do you take water from the earth and bring it to your mouth? It’s a matter of survival. Can you do it with profundity and with a light heart? Can you balance those two realms?

Then the water became other sources of food. Picnicking is such an important theme in the history of art, Manet’s “The Luncheon on the Grass,” (1862) for instance. Then there’s so many references in theater and movies and literature that have to do with dining and food. Before students start those projects, they do an immersion in culture, finding references in the world of art of people who have riffed on the concept of people having dinner together.

MY:

I think that it’s a rare thing and a credit to you, that you give so much of yourself to the students and are really trying to build up the next generation of great designers and artists.

AW:

I know how difficult the struggle is to be inventive and creative and the fear factor that goes along with starting a new project, because I’ve gone through it.

I’m a practicing artist, and I’m “practicing” being a teacher—you need to have a thriving, active life outside of the field of teaching. Otherwise, I don’t think you have anything to transmit.

MY:

I think you are great at demonstrating what practice can be. I would say you’re old school in some ways, but in terms of the empathic approach to teaching, very current. You definitely have the old-school conceptual rigor in your work.

I’m not really for platitudes or asking for advice. I think that people need to come to things a little bit on their own, but I wanted to know what you would give as a hint to others pursuing creative practice. I think one time you told me that, again on the subject of the rigor you put into work, you only feel satisfied at the end of the day if your mind and your body are equally exhausted. I felt that really encapsulated how you should be measuring yourself.

AW:

Just do it, exactly. Do what feels right. You do it because it’s comforting. It reminds you of your childhood. You use that material because you love the smell of it. That drives the intellect forward.

If you try too hard, and fear not coming up with a profound idea, it can cause such stasis in your life. But as soon as you start to make something—I don’t care whether it’s a good idea or a bad idea—I just want 16 ideas in 16 minutes, no stopping. Just keep moving forward, and the only thing I care about is quantity. Ideas will start to flow because it’s just a way of loosening up. It’s about a kind of whirling dervish idea. It’s like getting yourself into a frenzy of activity.

MY:

That is so true. What I think is also important is the necessary access to criticism when in a studio environment. Having a neutral sounding board is key to building distance between you and the work. I think people need to be able to emotionally remove themselves from the things they create. The distance allows you to be critical of yourself and in doing so actually be able to grow.

AW:

Self-critique, absolutely. That’s one of the dangers of working as a private artist and not having feedback. In the ’50s, you had the Cedar Tavern. All the abstract expressionist painters would go there at night and drink and have conversations about their work. Teaching is a kind of Cedar Tavern for me.

MY:

There you go. Back to dining.

AW:

Yes, back to drinking and dining.

MY:

Back to drinking.