“We’ve become too used to doing everything at the touch of a button, instead of adapting to what nature gives us,” lamented Celestino Ruivo on a hot July afternoon. The sky outside Ruivo’s home near Faro, in the south of Portugal, was tarnished by smoke, as a fire had started a few hours before in nearby Monchique. As I entered the property, I saw two, then four, then five solar cookers with different typologies—parabolic, funnel and box. The more we walked, the more models we found. The space is like a working museum, a lab for experiments: after all, as Celestino, a mechanical engineer and stalwart of a global movement notes, solar cooking requires experience, improvisation, adaptation. And it’s precisely this adaptation that is key for him: “a change of mentalities” is necessary, he exclaimed, tapping his finger to the side of his head.

With typical Portuguese hospitality, Celestino offered a coffee, a solar caroffee to be specific—a mix of coffee and carob from his garden’s tree, which is dried in a box solar cooker, and then ground in a stone mill that belongs to a friend. The mix is put in an Italian coffee maker on the Prince 15, a domestic parabolic solar cooker invented by his Indian friend Ajay Chandak, and in 7–8 minutes, it’s ready. As we started to smell and taste the caroffee, he turned to me with a smirk and declared, “don’t come too close to me, I’m infected,” slowly taking another sip. I looked around, frozen in disbelief until he continued: “I’m infected with the solar virus, and it can be contagious!” I laughed with relief; this thread of humor continued throughout a profoundly and contagiously inspiring end of afternoon.

The contagion spread by accident in 2006. Celestino drove a friend to Granada, Spain, for a solar cooking conference. When he dropped him, the huge number of solar cookers displayed was intriguingly seductive, so he asked at the entrance about registration—€100 for three days seemed reasonable. Lectures, films, seminars and demonstrations ensured the virus had found a new host. Once he returned home, he built one, then two, then three simple cookers with cardboard and reflective aluminum foil, using instructions available online.

There are multiple benefits of solar cooking, and they have been consistently demonstrated in academic publications. A key benefit is that solar cooked food, cooked at temperatures below 120 ºC, does not release AGEs (Advanced Glycation End-products), which are associated with various pathologies in contemporary societies. Solar cooking also preserves most of the vitamins, minerals and antioxidants in food. Burning fuels like cooking gas, kerosene and wood releases greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide, and continuous contact with these gases is a cause of major diseases. Solar cooking does not pose any of these threats.

The Algarve region, where the city of Faro is located, has over 300 days of sunshine per year, with very little rainfall. It is therefore a region that is particularly suited for this technology. For his eldest daughter’s birthday in 2006, Celestino decided to cook for 30 kids in one of Faro’s central squares, using only nine panel cookers. The parents then joined at lunch time, and there was enough (solar) food to serve 45 people. After several dozen trips to various continents to meet different inventors and enthusiasts, a strong, reliable network was built, paving the way for CONSOLFOOD, a biannual conference for knowledge-sharing around solar cooking. “Unfortunately, we are just a few [people], even after all these years,” Celestino explains. Frequent Zoom calls, webinars and WhatsApp groups kept the conversation going during the pandemic.

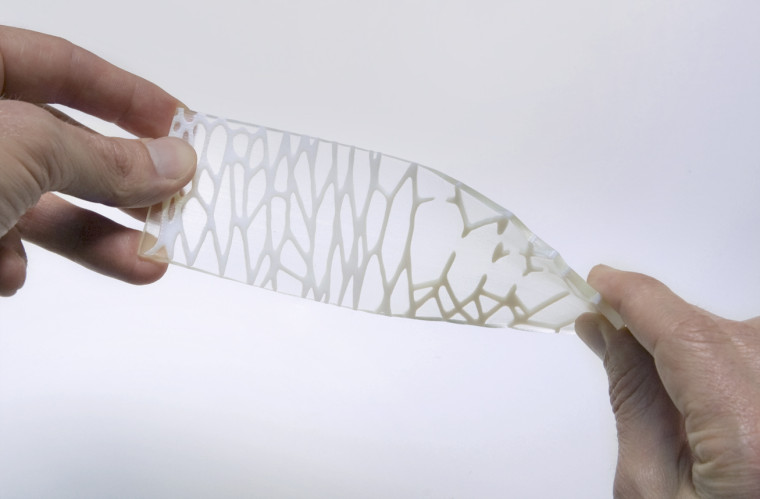

A parabolic solar cooker with a diameter of about 1.4m is identical in performance to a gas stove/oven, when cooking, for example, soup, potatoes, stews and rice. The funnel cooker is typically less powerful than a parabolic because although heat is concentrated into a single point, it is more distributed than in a parabolic cooker—funnels can cook most of the same meals as the parabolic but over a longer period of time. However, due to its multiple reflective surfaces, a funnel cooker slow cooks without the need for frequent monitoring, avoiding also the risks of food burning. It is also a design that can easily be recreated using cardboard and aluminium foil—there are plenty of tutorials online using inexpensive tools to teach children and adults alike. A well-designed box cooker provides similar results to an electric or gas oven, although more slowly. There are various other typologies including the evacuated tube solar cooker used to bake baguettes. The continuous improvement and introduction of new solar cooker designs is illustrative of a global community always searching for adaptation, improvisation and fine-tuning of shared-knowledge.

It was a little past 6PM and the sun was low in the sky when suddenly, Celestino challenged me to bake a cake. White and carob flour, two eggs, a couple of fresh figs and a bit of olive oil and sugar. The mix is done in less than 10 minutes and after 30 more, the cake is ready. No need to pre-heat an oven. A few leaves of lemon balm are dropped in a pan and in under 10 minutes the water is boiling—tea to accompany the cake we snacked on while I helped prepare the ingredients for his dinner soup. Celestino pointed out that 80% of his cooking throughout the year is solar, as it’s simply a matter of habit, planning and adapting.

The comfort of wanting to cook at any given time of the day expends unnecessary energy, an unsustainable comfort in an era when apps, notifications and the Internet of Things are constantly sold as the future. This centuries-old technology appears to be far more progressive and sustainable than what Big Tech offers. In this sense, innovation isn’t just producing technology that conforms to our lives, but an adaptation of our habits to nature. Yet, the systems of convenience our daily routines are organized around—the instantaneity of gas, oil, coal or electricity, design of housing, city planning—make solar cooking and other sustainable ways of cooking an uncompetitive option. It’s a systemic problem involving many disciplines—it requires effort and mutual support.

In 2020, Chilean solar cooking researcher and architect Pedro Serrano, wrote an open letter to all CONSOLFOOD participants, saying that “a device that can cook, needs few repairs, lasts for years and doesn’t consume fuel is not the type of profit-making product required to support a market-based economy based on continuous growth.” [Editor’s note: Read about the degrowth movement in this conversation between Jamie Tyberg and Lexie Smith.] But technology is not the central lever for instigating fundamental change at multiple levels. Serrano notes that food is a “socio-cultural issue that includes ingredients and customs, health and lastly technology.” Emphasis must then be put in creating the infrastructures that allow the use of solar cooking to be widely disseminated, even if it means getting rid of deeply ingrained and imposed habits.

Being ‘infected’ by the solar virus is not an uncommon metaphor in these circles, as this small but global movement continues to push a technology that has existed for many centuries. This virus is at odds with key power struggles in societies around the world; its technology is marginalized, inconvenient. With collective will, it can spread. Pedro Serrano, the “solar friend” Celestino drove to Granada, made clear the radical potential of this distributed, accessible and free source of energy, signing his open letter with the following words, just after his name: “infected and contagious.”

Thanks to Celestino Ruivo, Karen Lacroix, Dave Oxford and the Center for Other Worlds.