Amongst those who call themselves food designers, there is no consensus for where the boundaries of the practice lie. Whether a designer is creating new dining rituals, reimagining food groups or agricultural systems, it’s often easier to explain in the negative—food designers are not stylists, chefs or food scientists. But for the pioneering Dutch designer Katja Gruijters, 20 years of answering the question, “What is a food designer?” has led to a deceptively simple answer: I tell stories with food.

Sweet Velvet introduces consumers to edible flowers through a candy collection featuring rose petals, violets and lavender buds. There are over 500 kinds of flowers that we can eat. Collaboration with Papabubble, Amsterdam

Sweet Velvet introduces consumers to edible flowers through a candy collection featuring rose petals, violets and lavender buds. There are over 500 kinds of flowers that we can eat. Collaboration with Papabubble, Amsterdam

In 1998 Gruijters graduated from Design Academy Eindhoven with a senior project that created a consumer brand of vegetarian meats that were being developed at Wageningen University. Working with ingredients like seaweed, nuts, and high protein doughs, Gruijters proposed a future product line of plant-based meat alternatives and designed biodegradable packaging for five consumer-facing concepts. To further her research, she took an internship with a Dutch meat factory and after the success of the senior project, the brand offered Gruijters a full time position to further develop her concept. Over the course of the next two years, Gruijters held in-house positions with major food manufacturers—from pasta makers to a frozen vegetable company. Although the food industry welcomed her expertise in their organizations, the industry was unsure how to define her position in the most simple way, a business card, and Gruijters gamely suggested the term food designer. “They want to give me a fancy name like product designer or product manager and I said, ‘Come on, I’m not a manager. I’m a designer and I’m working with food, so maybe you can put food designer on my business card.'” By 2001 Gruijters started her own studio and developed a manifesto of sorts that she still uses to explain her practice and the burgeoning discipline: Food design is an interfaith exploration and definition of everything that concerns food—production, distribution, identity, enjoyment, nutrition and digestion.

For the launch of Castello Cheese, Katja Gruijters studio created an interactive cheese architecture installation to highlight the ways that cheeses must be cut to make the taste and texture stand out. Photo courtesy of Studio Katja Gruijters.

For the launch of Castello Cheese, Katja Gruijters studio created an interactive cheese architecture installation to highlight the ways that cheeses must be cut to make the taste and texture stand out. Photo courtesy of Studio Katja Gruijters.

Gruijters’ approach to her food design practice is varied, but at its core it is collaborative and research driven. “I’m specialized in food design, and within this area I like to work with experts like graphic designers and chefs to create a complete product line or an experience, or I’ll develop my own point of view,” Gruijters explains. Her work is also firmly based in educating both clients and future food designers the tenets of the practice—leading workshops, helping food companies in their design innovation, developing curricula or teaching. But food, with its overlapping systems that touch everything from growing ingredients to distribution, professional kitchens to food waste management, is infinitely complex and deeply personal. To frame the problem, Gruijters encourages her team to, “define the problem; then you can explore everything around it and even go a step backwards to go forward.”

In Gruijters recent book, Food Design: Exploring the Future of Food, she presents 38 projects organized under 12 themes critical to her vision for designing a more sustainable food system including explorations of ingredients like seaweed, bread, new proteins, candy, flowers and processes like food waste reduction and dining rituals. “I also use my work to create a discussion,” Gruijters explains. “I don’t necessarily want to give my personal opinion but I’m more interested in the opinions of my guests, and depending on these reactions I develop some elements further into a product or service.”

A menu of foraged ingredients from a Survival Food workshop. Photo courtesy of Domaine de Boisbuchet.

A menu of foraged ingredients from a Survival Food workshop. Photo courtesy of Domaine de Boisbuchet.

An example of this exploratory process is the series of Survival Food workshops that the designer has held over the years in a number of different cities including Madrid, Singapore and at the summer design education camp Domaine de Boisbuchet. The framework for the workshop invites participants to forage for ingredients and focus on inventive preparation and cooking techniques to produce an experimental meal. The framework is flexible enough to repeat across geographies, in different cultures and in different countries and over time, has surfaced some interesting observations around scarcity/abundance and how it might spark cultural creativity. “You discover the local ingredients you are surrounded by and use them as inspiration so you can get creative with how you use these unnoticed ingredients; because you have to be inventive when you’re creating something from nothing.”

Diners enjoy a “Date with Nature” at Boisbuchet courtesy of Gruijters’ Survival Food workshop participants. Photo courtesy of Domaine de Boisbuchet.

Diners enjoy a “Date with Nature” at Boisbuchet courtesy of Gruijters’ Survival Food workshop participants. Photo courtesy of Domaine de Boisbuchet.

At Boisbuchet, the participants developed a concept called, “Have a Date with Nature,” where diners were invited to enjoy a meal on a wooden dock, and the table was situated overhanging the water. “People are really sitting on the dock and hanging with their feet nearly in the water and then eating with this incredible view on the lake,” Gruijters recalls. “So it was really in the context with nature and the food.” The surrounding lake water was used to cool a summer gazpacho and a stone bread oven, where the participants baked fresh bread, welcomed guests at the head of the table. While sitting on the dock, diners were served bites on skewers that were mounted into a bespoke wooden table, built to match the length of the dock.

At the Stedelijk Museum, visitors are confronted with the wasteful byproducts of consumerism in an edible installation. Photo by Marieke Wijntjes courtesy of Studio Katja Gruijters.

At the Stedelijk Museum, visitors are confronted with the wasteful byproducts of consumerism in an edible installation. Photo by Marieke Wijntjes courtesy of Studio Katja Gruijters.

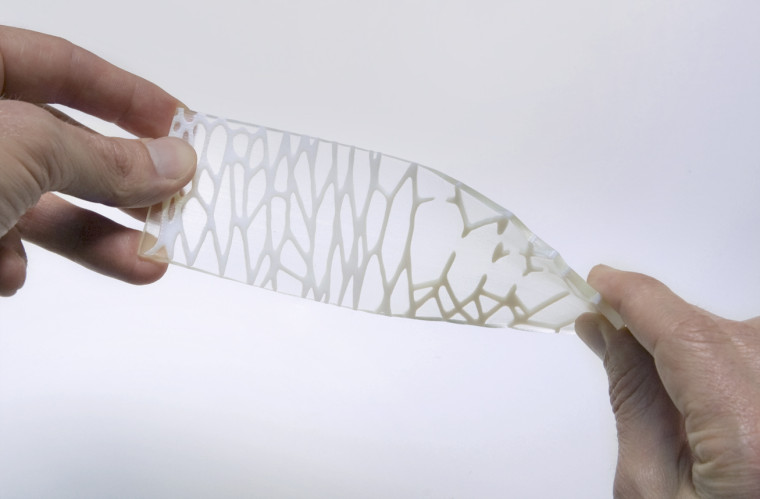

Another theme that has been consistent across Gruijter’s work is the theme of preservation and the extreme realities of overproduction and food waste. In 2010, she designed an edible and interactive installation for the Stedelijk Museum, Beautiful by Nature, that challenged the regulations that affect the food industry. Through preservation techniques and a showcase of imperfect fruits visitors were encouraged to confront and taste the wasteful byproducts of consumerism. More recently, her studio created fruit leathers for the Het Nieuwe Institut, Rotterdam during the Temporary Fashion Museum. Engaging with the fashion industry, guests were invited to make clothing out of the edible fruit leathers, taste edible perfume sprays and “design” their own tasting menu by trying different color combinations of coded Food Cubes that had been processed using a textile production method that raises the surface to create a fuzzy texture.

At the launch of the Temporary Fashion Museum visitors enjoy fruit leathers and foods that had been treated with a textile design process to raise the surface into a fuzzy texture. Photo by Pim Top courtesy of Katja Gruijters Studio.

At the launch of the Temporary Fashion Museum visitors enjoy fruit leathers and foods that had been treated with a textile design process to raise the surface into a fuzzy texture. Photo by Pim Top courtesy of Katja Gruijters Studio.

“How are you going to transform the thoughts you want to discuss or speculate into a design or a strong image so it becomes interactive?” Gruijters poses. Over the past 20 years her studio has been exploring the myriad ways that food can be a material for this type of exploration. Eating has always been a social activity for humans and as we consider the future of food, these interactions will help us ground new ingredients and experiences in the familiar tropes of dining and ritual. Gruijters’ work as a food designer shows that the true interaction is not so much between the end user and the material but as she argues, really to, “design interaction between people.”