The work of The Center for Genomic Gastronomy is interactive, tasty and provocative—an unlikely combination in the world of food design. Founded by artists/designers Zack Denfeld and Cat Kramer in 2010, The Center is an independent research institute confronting the systems, governmental policies, corporate interests and consumer assumptions of our contemporary food culture and presenting it on a plate.

As the newest contributor to MOLD, we took a moment to chat with Zack and Cat to learn more about the history of the Center, their practice and their current projects. Look forward to learning more about their projects and process on MOLD.

MOLD: Can you share a brief history of The Center for Genomic Gastronomy?

Zack Denfeld and Cat Kramer: Food should be an opportunity to tell a story. When we first met in 2010, one of us had been working on an ice cream truck that tried to make snow ice cream, and one of us was doing food research with art students in Bangalore, India. We were both really interested in the direction biotechnology was going, but were not seeing the ways in which the industry was acknowledging its role in the development of food systems.

We believe artists are really good at exploring and challenging the social norms and metaphors that emerge, and we saw an opportunity to play a role in developing narratives around biotechnology and food.

At the time, many of the existing biotech metaphors came from engineering cultures—most of which did a poor job of acknowledging that life is actually quite different from computer code or mechanical parts. This disconnect inspired us to start thinking about how we could we use food and gastronomy as a lens to challenge these existing assumptions. Since then, we’ve found that the framing of biotechnology itself is really a poor metaphor for exploring the interactions of humans and other life forms. At this point, we’ve gone way beyond the initial idea of food and biotechnology; we’re interested in creating metaphors that look at the whole system.

From the Doomer Food project, a collection of food and financial data which represents the fears surrounding peak oil, global climate change and economic instability.

From the Doomer Food project, a collection of food and financial data which represents the fears surrounding peak oil, global climate change and economic instability.

The idea of “Genomic Gastronomy” also came out of molecular gastronomy, which focuses on chemistry and a reductive approach to food: How do we understand the base elements of each component and build up from these component pieces? The Center For Genomic Gastronomy takes the opposite approach: “How can we look at a whole system—from its ecological, economic, political, social, aesthetic, technological, health and other drivers—to create a dish on a plate? And what would this look like?” So we came to define Genomic Gastronomy as the study of organisms and environments manipulated by human food cultures.

What unique role does speculative food design have to play in our food futures? Why is it important?

Speculative food design uses the tools of design to imagine and prototype alternative cuisines, future food systems, and experimental ways of eating. It can be used to inspire new products and services, critique existing food design practices or as a method for conducting ethnographies of eater or ingredient experience. We’re interested in a “figurative” or “realist” approach to speculative food design as opposed to the more typical “diegetic” and fantastical speculative food design.

Figurative speculative gastronomy involves creation of food that can be consumed by humans, though it need not taste good or be nutritious. In the figurative mode audience members move from viewers to active participants. They are pushed beyond commenting on a future scenario in the abstract, and are confronted with the reality of consuming and incorporating into their body something unusual or uncomfortable.

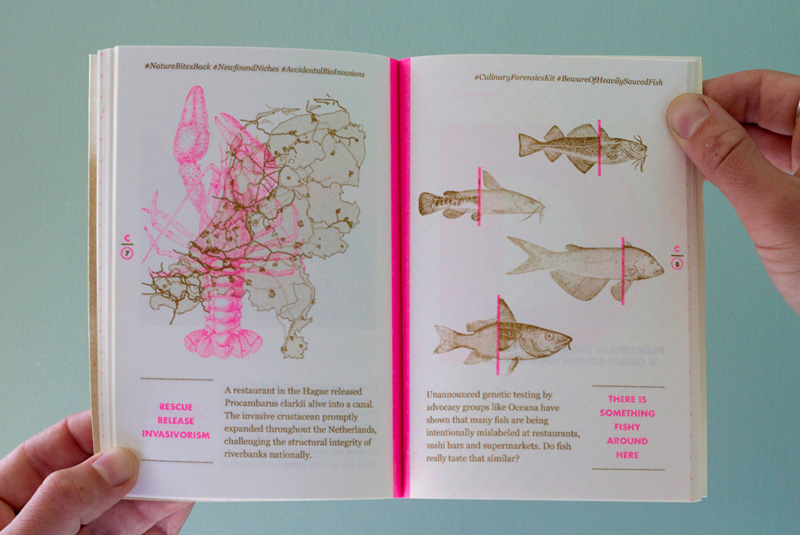

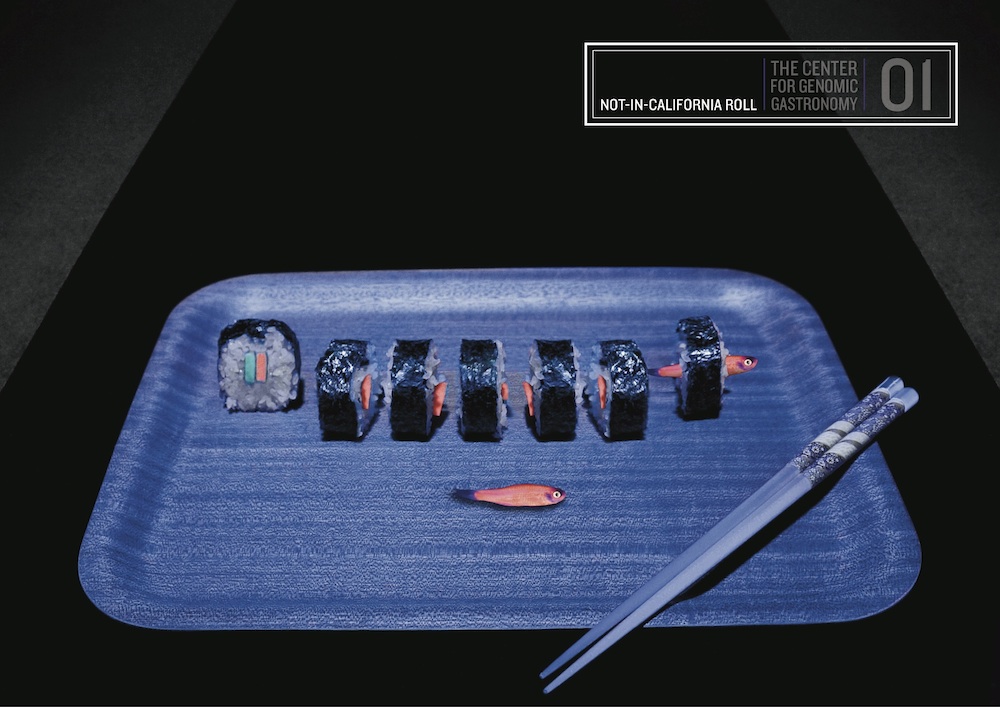

From the Glowing Sushi Cooking Show, a project that confronts consumers with genetically modified organisms (GMOs) using GloFish, a commercially available product marketed as a pet.

From the Glowing Sushi Cooking Show, a project that confronts consumers with genetically modified organisms (GMOs) using GloFish, a commercially available product marketed as a pet.

Figurative speculative gastronomy shares many qualities with diegetic work, but more emphasis is placed on the experiential, haptic and edible aspects of the fiction that is being conjured up. Figurative creations can combine images, media, sculpture and performance, but what sets them apart is their use of food that can be consumed.

Speculative gastronomy is driven by the way people use metaphors to define their values and preferences. Because metaphors are the primary vehicles that people use to understand their world, the Center attempts to create and develop metaphors that appear less frequently or that do not already exist. We extend these metaphors in ways that tell new and vivid, yet plausible, stories. We explore angles of food, eating and agricultural systems that aren’t covered very often, and we try to maintain the complexity of these systems in those stories, rather than diminish it. The outcomes push people to test their own world-views and assumptions, doing it in ways that sidestep the more exhaustive and exhausting discussions about technologies and policy.

For example, our project Vegan Ortolan challenges chefs to create a vegan version of the cruelest dish ever invented. They are given a flavor profile of an entire bird and asked to re-create the whole animal out of vegan ingredients. The project imagines a future that moves beyond fake sliced meat on a plate, and asks: “What if the future of protein has more to do with human labor, care and a connection to history than an industrialized processes that homogenizes ingredients for the sake of mass quantity?”

The traditional preparation of the ortolan bird in France demands that they are captured alive, force-fed, drowned in Armagnac and eaten whole.

The traditional preparation of the ortolan bird in France demands that they are captured alive, force-fed, drowned in Armagnac and eaten whole.

Recently, we’ve been using the term “cultural exorcism” to describe the project. While typical speculative food design often shows the future of meat as a steak in a petri-dish, we’re hoping to introduce a new story: one that is both refined, pure, tasty and anti-industrial. The embodied experience and the metaphor of Vegan Ortolan create a moment of dissonance or humor between the old and the new, the cruel and the caring, and the original and the recreation—where people actually have to stop and think, or laugh or be confused, or take time to process it. To us, this is what is important about speculative gastronomy.

What is your typical process for developing a project?

Projects created by the Center first come out of exciting, inspiring, or sometimes frightening food-related news or technologies that have a set of narratives forming around them. This is followed by research from a critical perspective that incorporates perspectives from biology, ecology, culture, etc. The realization or materialization of this research comes from goals of telling new stories and creating new metaphors that are engaging and communicate with our audience, whether they be the public, scientists, chefs, etc.

The Planetary Sculptural Supper Club has traveled around the world. Where did the idea come from? How do the cities where you have hosted these events inform the issues you address and menus you create?

Planetary Sculpture Supper Clubs are dinner events that explore the ways planetary patterns change in response to how and what humans eat. We study food from the prospective of biology and ecology and look at how chefs, restaurants, and non-ag people have upstream consequences based on their decisions around food. Planetary Sculpture Supper Club was created as a way to investigate and taste some of these stories of human choice and decisions, and manipulation cause by human food culture.

We have a few dishes that can take on location-specific forms. For example, the Smog Tasting dessert dish consists of a set of meringues representing different cities. We transform air pollution levels into spice portions which are added to the meringues, so eaters can taste and compare smog levels in their city and cities elsewhere.

We also have created dishes that are more specific to the given Supper Club’s region. For example, we created three menus for the Lisbon Architecture Triennial, which drew on Portugal’s history, local architecture, regional foods, and the three alternative scenarios: Decadence For All, Recipes For Disaster, and Slow Expectations.

In Portland, the Center created an Oregon-specific dish entitled, Wheat Wars that illustrates the story of wheat in the state directly following the GMO wheat scare of 2013. Exploring wheat production, exportation, GMO experiments, and health related issues like gluten intolerance, the dish surfaced topics from industrial agriculture and biotech, to politics, commerce and culture in Oregon.

From the Planetary Sculpture Supper Club, Lisbon

From the Planetary Sculpture Supper Club, Lisbon

What can we expect in the coming year from The Center?

The Center For Genomic Gastronomy will be in residence at V2_ in Rotterdam, The Netherlands this fall. We’ll be working towards the first steps of a feature-length film exploring the idea “we have always been biohackers.”

Also, our next issue of FoodPhreaking is nearly complete and should be out in the next few weeks.

We are hoping to organize a research trip to Asia in the fall or winter for 2015.

And we have recently added a new member to our research team, Gabriel Harp.

That’s the update from the road.