For Gala Porras-Kim, the museum is the metaframe. Across her practice the artist has investigated how museums affect how we see and think about artifacts, and by extension art and history. With this lens, Gala has melted down ancient ice cores and cultivated mold on objects drawn from the British Museum’s collection. In doing so, she’s introduced ecological timescales to institutions, pushing us to reimagine how we might implement more interdisciplinary and interspecies approach to collecting and preserving history.

Upon walking into Gala’s exhibition at the Storefront for Art & Architecture one is immediately enveloped in a hazy blanket of steam. A nostalgic, mineral scent hangs in the air. Wet and sticky, The motion of an alluvial record offers a multi-sensorial experience rarely encountered in art institutions. For this exhibition, one part of Storefront’s yearlong series of programming and installations examining swamp ecologies, the artist has constructed a hothouse. Within this structure is a long wooden trough holding mud Gala has transported from the swamplands of the Yucatán peninsula. The exhibition is a rejoinder to the climate-controlled environs typical to arts institutions. By placing an lively, messy, fluid object at the center of her exhibition, Gala pushes the institution to play by a new set of rules, asking questions like: How might we preserve something that is living? and What does it mean to build a wet archive? With these questions, she prompts us to reimagine the museum, conjuring forth visions of new models for the institution.

Earlier this fall, Gala and I sat down for a conversation on the exhibition and her practice. We talk about adopting interdisciplinary taxonomies, air conditioning as decontextualization, and how Marie Kondo inspired her own work with museum collections.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for content and length. The motion of an alluvial record is on view at The Storefront for Art and Architecture until Dec 7, 2024.

Isabel Ling:

Let’s start with the mud. Could you tell me a little bit about your experience with sourcing the mud for your installation from the Yucatán? What was your encounter with the swamp?

Gala Porras-Kim:

Before even going to the site, I went in with the idea that I wanted to make something about the climate of a site. Many of my previous works are about how institutions regulate the environment in which art gets viewed and stored. I spend so much time in tropical areas that I began to wonder how that viewing of institutions actually would affect the production of the works from the front end. People that might want to make a work about the hot, muggy climate have to take the extra step to translate that into a work that likely will exist in a dry viewing space.

I thought, ‘How would I make a work that would require a muggy environment to actually exist?’ Then it became evident when we went to the swamp, and I saw the mud. The idea came through learning about how the Ancient Mayan civilization came to an end because of drought. It’s reflected in many of their documents and architecture and carvings, how they were thinking about water, like water irrigation or how to control the water systems, because people were freaking out because of the drought . So this particular site we went to was at the end of a river. So everything, sediment from anything upstream comes down and ends up at the base. I was thinking about what type of particles constitute this mud, every building that was built and might have eroded at some point into these miniscule pieces.

So then I was thinking about sedimentation in general, and how in geology, dry things become stratified. Geologists study history through these very particular layers of information. Those layers follow a singular timeline from oldest to youngest, etcetera. But because the mud has been wet the entire time, these particles of different times don’t land on top of each other—they are always mixing. It follows a cyclical timeline, one that mirrors a Mayan way of thinking about time as not such a straight line. And so I was thinking, ‘That’s the work.’ The work is the particles moving and mixing with each other now. So, to be able to maintain this work, it has to be wet, because if it dries, it will stratify and it will not move.

We made this idea with Storefront because the space was small enough to experiment, because I’ve never made an environment like that, and it is actually an institutional challenge to be able to maintain this work so that the particles can move in the water, but they are thinking about architecture and environment already so they were able to make it happen!

The other works in the space are made with condensation. But it’s not just any condensation, it is the particular condensation made with the atmospheric conditions of the Yucatán. So, for example, there is one called Chaac’s Tears. It’s a portrait of the rain in the Yucatán.

Chaac is the Mayan rain god, and I wanted to make these paintings or portraits because I love old-timey paintings. But then I was thinking thinking of how to represent this particular rain in the gallery. . So we recreated the atmospheric conditions, which is the temperature and the moisture level of Yucatán, and the condensation that collects on top of this piece of glass is a portrait of that rain.

IL:

It’s interesting that you mention this project was inspired by Mayan timescales and the end of the Mayan civilization, because right now we’re in what feels like the end of some type of empire. And it also seems that Yucatán is in a drought as well right now, right? So what was it like for you to sort of experience that when you were physically in the Yucatán?

GPK:

Before I answer this question, I just wanted to say that we’re going to try to show the second half of the project in the hottest month of next year at the Yucatán. As the second part in a two-part project, we would not need a building around it, it would just be outside.

For this work, I didn’t think about the drought specifically, you know the drought being a circumstance of the Mayans and the condition now. Of course, I’m thinking about drought in my personal life because I live in California… and in my subconscious it’s a looming threat. But the drought is not the subject of the work. For me, the more interesting part is about how the viewing of art changes according to the conditions of the institution. Or, how historical material has a particular function that is changed once they enter these arts-viewing spaces. So that’s my main interest—how the institution is making new meaning by narrowly reframing things. . Because, in theory, we as artists have the biggest field, we can make anything. But then it becomes limited to a particular type of viewing that’s made available by our institutions. Of course, the museum is not the only institution in which we see art. We can just do it outside on our own, but it is an important part of the relationship of an artist, their work and the audience.

So I was thinking if I would have grown up in a tropical climate, and I ended up making these works about climate that would not just be a representation of climate, but the actual climate, then I would have to really adjust my range of expectation of where this work could be shown. And so I would have to change the work or, if I wanted to keep it as I imagined it, then either the institution has to accommodate it, or I have to figure out where else it can be installed. Which is not necessarily our primary job as artists and it should be already resolved. Especially by institutions who say they want to show the “art of our time” and works from and about tropical areas.

IL:

It’s interesting because you talk about climate control, or what is essentially air conditioning. In parts of the world air conditioning is a given, if not a necessity, but elsewhere it’s a privilege. I think this relationship will shift as climate change progresses. But it’s also an interesting apparatus for the institution to separate itself from its context, right? I wanted to understand a little bit more about what drew you to climate control. Was there a specific moment that shifted you into thinking about it?

GPK:

I can’t particularly pinpoint one moment, but I do think a lot about conservation and how things get translated when they go into museums. Especially with more encyclopedic museums, where they have objects that weren’t made to be there originally. How does that change the object itself? I go to Puerto Rico as much as I can and recently, I was in Hong Kong, too. When you go into institutions there, the biggest expense is keeping the moisture out of the building. And so, like you said, it’s actually separating the institution from its natural environment, because it holds within it, works that are made in a way and from places that don’t need to be as climate controlled. I was just thinking about how mediated that process is, because you enter into this environment that is so starkly different from the reality of the climate there. My questions are not necessarily about what is wrong with the institutions, but more about how people are rethinking and engineering them so that we can have a lot more possibilities. Whether it’s design or architecture or methodology, I’m interested in possibilities that can manifest that future, one where the container around objects might be able to change to accommodate whatever the conditions required by what they hold inside. Not just climate conditions, but any conditions they might need, whether it’s spiritual conditions or ritual conditions, etcetera.

IL:

In some ways, climate control seems like a tool of conservation for some museums. I’m curious what role you think climate change will play in how we think and practice conservation?

GPK:

Well, it’s not even going to come down to anything related to conservation, but rather money, because that is what is really prohibitive at some point. The institutions have the almost impossible task to materially preserve whatever is in their collection for as long as possible, which feels like forever. But, it’s literally impossible. No matter how good the conditions or the technology might be, everything is going to go away. It might take longer or shorter, but it’s going. So I think that once institutions make the conservation of objects not just focused on material conservation, that will allow for other conditions to be thought about that might resolve some budget and space issues.

IL:

To me, the institution feels like your medium. What drew you to it?

GPK:

I am not attached to a particular medium, but I am interested in the production of knowledge. The museum is a site where I have learned a lot but I also recognize the extensive mediation that has occurred between an author and the public. I think that as artists, we frame perception all the time, but the museum is actually meta-framing as well. The objects we see from collections are actually co-authored, not by an individual person who made it, but by everyone who has come in relationship to it, which to me it is more interesting than a single author version we are presented with.

IL:

It kind of goes back to what you were talking about with what the ideas of authorship have to do with the mixing of the mud too, because it’s not traced back to one single moment or person. I kind of wanted to go back and talk about your relationship with Chaac as well as the Mayan understanding of time, how did that factor into this show?

GPK:

I had previously made a big project about the objects that were dredged from the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, which was the ritual donation pit for the Mayan rain god, Chaac. For me, the impulse to understand the current context of these objects was to think about an ancient person who thought that those objects that they put in there were going to be in relationship to their own spiritual life onward. So what do the contemporary process of bringing those objects from this sacred site into an institutional site look like. How do they change that relationship, whether it’s to the site itself, to that original person, [or] to a spiritual entity?

It was almost by chance that the structure of that project ended up being so much about wetness and dryness. It was because those objects were preserved by being submerged underwater. So as soon as they take them out, they aerate and start falling apart. The institution’s argument is that we can preserve it because we have climate control. But it was already preserved, you see. And so now, thinking about those objects being in the storage where it’s climate controlled and the moisture, which is, in theory, the rain, is being kept away, it’s actually damaging the spiritual function of that material for that ancient person.

I think conservation notes could include these other considerations like , ‘Okay, to retain the spiritual integrity of this object for that person, it needs to be somehow, in relationship to the rain.’ You know, there’s a very simple version that we get to know as an audience that’s like, ‘Oh, now this is really good for this thing, because now we can control the material life of this work, and we’re putting a lot of energy into it.’ But there are probably very practical, not too complicated steps to retain those spiritual conditions too. Just because we don’t believe those things ourselves doesn’t mean that they don’t exist for someone else.

IL:

Have you watched the movie “Dahomey” that Mati Diop just put out?

GPK:

No, I haven’t!

IL:

It’s about the repatriation of twenty-six sacred objects from this museum in Paris back to the Kingdom of Dahomey in Benin. It’s really interesting, because she stages this debate between the youth, and they talk about how the Kingdom of Benin has built this museum, a very traditional Western museum, to place these sacred objects in. But, it’s this sterile environment, and you have students asking why they didn’t return the object to the villages it’s from, to an environment that’s more in alignment with their original spiritual function. I’d love for you to talk about this spiritual dynamic you’ve mentioned and how it functions in your practice.

GPK:

With spiritual life, it’s just seeing who the stakeholders of this particular object are. Because every single object has had a different circumstance and different stakeholders throughout time. Think about mold. If something is buried, it’s meant to decay and might now be a buffet for mold. When you take it out and clean it, you’re de-accessioning it from the world of the mold, which is also a stakeholder. You know what I mean? The mold is like, ‘Dude, you took my lunch away!’

So it belongs not just to humans, but also to the environment. We don’t have the mental capacity to even recognize all of the entities that interact with this material. In a sense, it’s just at least trying to recognize the ones that we might know, and then imagine having that conversation with those entities about what to do with this object. Sometimes, acknowledging that the object had some essential function for someone’s spiritual life, becomes more important than what we can learn from it on the day to day. Even if you put something out and it’s not in a climate controlled environment and the mold will be eating it soon, slowly, we still are able to learn about the object through that process.

The way I see it, it really comes down to taxonomy, registration and conservation, because the way that things are registered right now is like this: ‘this is x historical object, and these are the conservation notes for it, and these are the environmental circumstances that it has to have,’ but as a ritual object, it has other requirements. It needs to be in the site, it needs to be handled like this, it has different viewing restrictions, etc. And so what I hope in the future, which I think is really possible, is for institutions to cross reference different types of taxonomies that already exist, like biological, spiritual, or, historical. For so long, they’ve been siloed so now we only sees that as ‘food’, or only sees it as ‘history’. But I’m like, just link that together, and then you can at least see how this singular object is operating in all of these fields, which is actually way more interesting than just, ‘This is a plate. It was historical. It was used to serve this dish, and now it doesn’t . But obviously, if you take it out of this case and put pasta on it, it can work as a plate. You see, it’s a mental block,a taxonomy block I mean, humans are amazing, the amount they can ignore or forget, like, facts completely removed from their reality. Because when you see a historical object in a collection, but you also have one of those at home, you see one as different even if they are the same. And so that part about framing of perception is really interesting to me.

What is important to me now is how to recognize what a good way of doing things could be and hold it temporarily. ,‘This is the way that we want to show and display and preserve and catalog things today’, but 10 years from now, five years from now, it might be different, because the world is changing around us and we don’t need that material to function in that particular way anymore. You know, our willingness to accommodate non-human perspective is probably going to be a thing. And the institution itself is changing now it’s more diverse, and now we have to deal with it having more perspective, you see.So, in a way, the challenge is thinking about these processes of moving into different policies, and ways of working, in a longer timeline, because people want to see that happening, like right now.But the museum moves so slow, so I like to think about it in the objects timeline.. I’m like, ‘this object is 1000 years old, like 200 years of it being in a case, it’s not his whole life because it’s going to be something after this historical stint it is having, it’s going to have a future beyond the museum.

IL:

Yeah, one hundred percent. I’m curious, we touched on this a little, but what does a future museum look like to you?

GPK:

I think, in a more concise way, is more thinking about how institutions and the objects inside of it have a two-way relationship. The institution changes the taxonomy of an object when it goes inside by making it historical. The object enters into the perception of what we think goes in an institution, right? But in the same way, once it is brought into the museum, it also comes with all this baggage of previous contexts, and so it’s also changing its surroundings according to that history For example, if there’s a body that goes into the museum, where do bodies go? They go in the ground and they get catalogued a particular way in the morgue. There are already systems to deal with, you know, dead people. And so, yes an old dead person is historical, but still a person. The point is that once you put them in an institution, it becomes a cemetery or grave site, because the institution is also defined by the things inside of it as well.

IL:

I think that what’s powerful about your practice and also restitution, is that it feels like a very tangible exercise in speculative imagining and reimagining. I’m curious about your references, as an artist, I’m sure you don’t make work in a vacuum. Is there any one that you sort of draw from or draw or work alongside with?

GPK:

There are artists I like but there’s so many different frames of reference. Many of the works about collections came from reading The Art of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo. She talked about our own personal collections and our emotional connections to why we keep stuff, how we organize stuff. I was literally listening to it just to clean my house. Then, because I was thinking about museums at the same time, when she started talking about those things, like how people are having a difficult time getting rid of things, I was like, ‘I literally just had a conversation with a museum that cannot let go of some things’. So the references come from trying to recognize how these institutional structures are actually part of our day-to-day life. We have our own collections, we have our things, we have our own biases. We let our own things decay or not, you know, like, are you comfortable throwing peels away or not? This morning I was thinking, ‘Oh, my dad was peeling an apple.’ I normally just eat the whole thing, and I was thinking that there is one part that is allowed to decay and one that is for consumption. There are small choices like that in day to day life that make me wonder where that comes from and recognizing how those small things snow ball into big collective choices we are making.

IL:

Yeah. It’s like our everyday behaviors that sort of accumulate into our ideologies.

GPK:

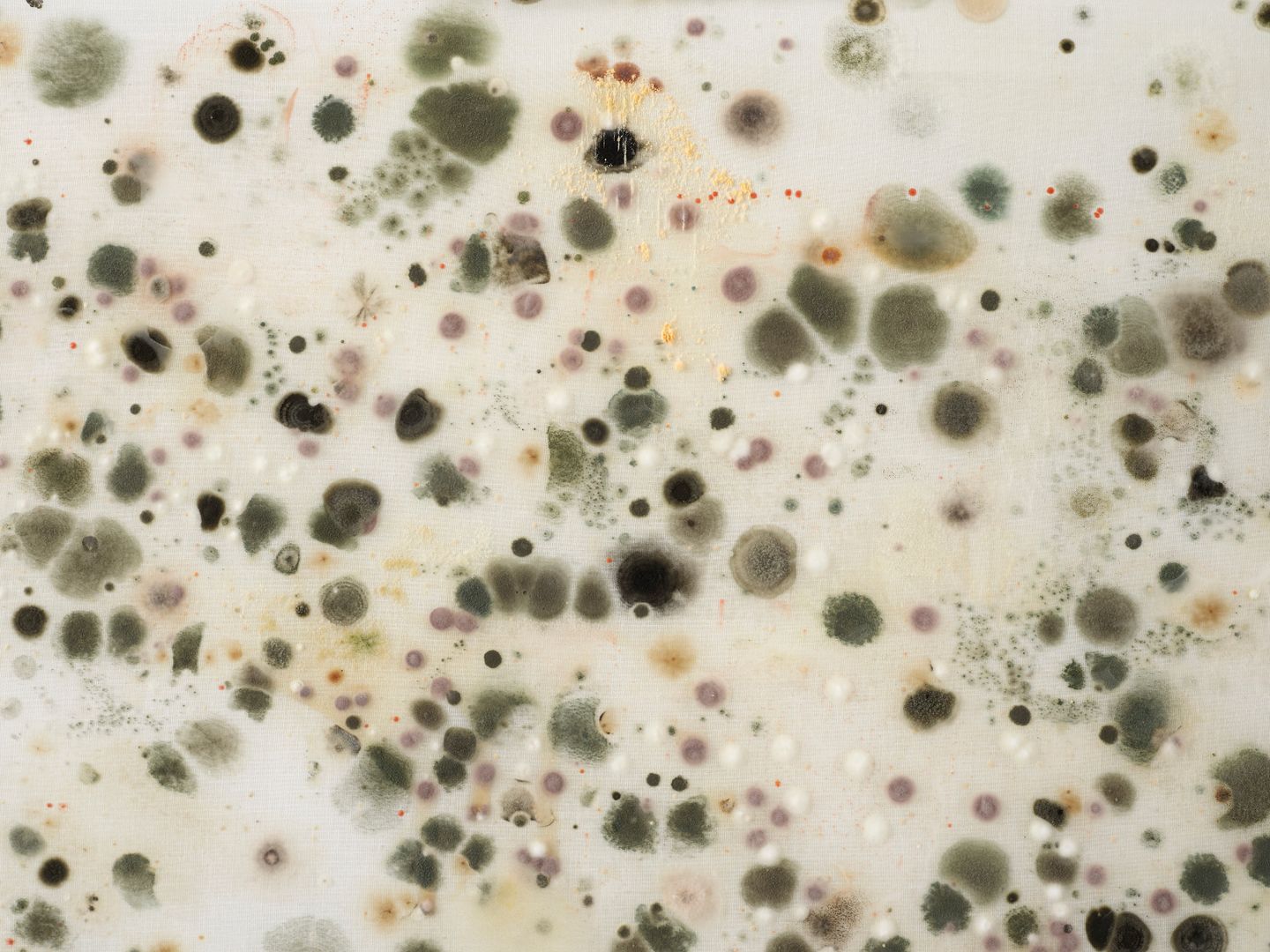

When I got the message that I was doing an interview with MOLD, I was surprised by the name. Did you see this mold work I made?

IL:

No, I haven’t! What made you want to work with mold?

GPK:

I just was thinking about how things leave the museum, like besides through deaccession policy. So a way was through the mold, because the mold is eating the collection, and thats how it can be transformed and ‘leave’ the museum. So the work is made with mold collected from the storage of the British Museum. We gathered the sample because the mold’s body is constituted of that historical material. And when the spores are propagated, you see the actual collection growing in this new shape, right? And so that’s what this work is. It just gets remade every time. I can’t anticipate what the form is going to be, no, and so you essentially are just collaborating with this environment I was thinking, ‘I’m just building the stage for the mold to do its thing, or not, whether it wants to or not, and then at the end of the exhibition, it gets destroyed.’ And so that’s why it’s a perennial showing, the title is Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing You know, every time it gets regrown is a new showing.

IL:

It’s like, you’re finding the loopholes for objects to leave a collection.

GPK:

It’s not a loophole. It’s more like, ‘if you’re going to do it this way, then do it all the way” but there is a practical limit to these methodologies so they can’t do all the way. Because they have a cultural objects, and those are always changing, they can’t be fully represented within a system meant to hold scientific information which is meant for unchanging facts. The way collections are understood now comes from understanding natural history collections, but the way we think of nature within science is different from how it operated in culture, so the infrastructures to understand them should reflect that.