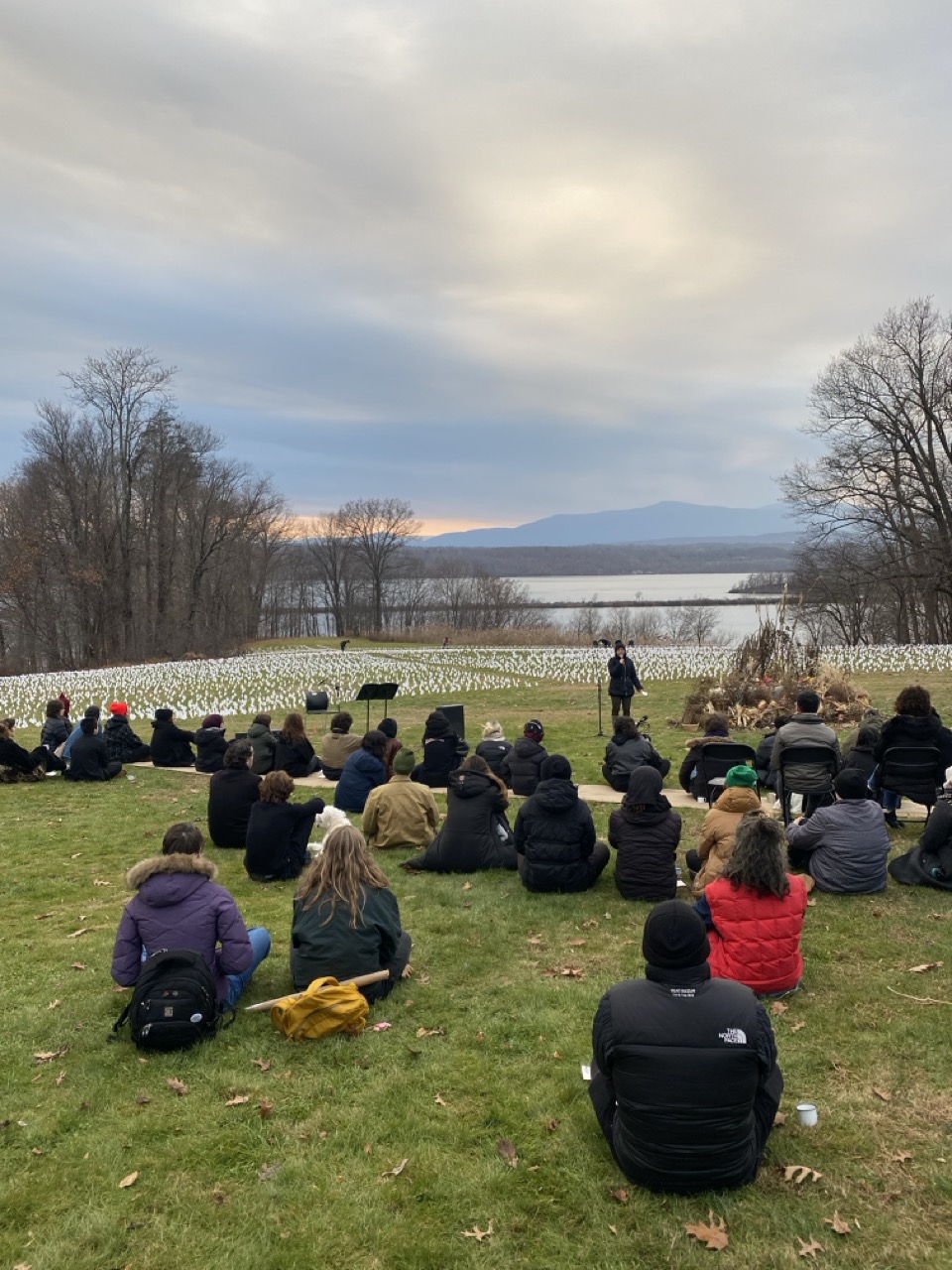

On a grassy bluff overlooking the Mahicantuck (Hudson River), thousands of white flags fluttered in a chilly December wind. The setting sun cast vivid color onto the hundred or so people gathered at Bard College for a solemn moment, a funeral for more than 16,000 Palestinian civilians who had then been confirmed killed by the genocidal bombing campaign launched by Israel two months prior. Each flag planted in the lawn represented lives cut short in Gaza, and increasingly in the West Bank, with many more injured and countless others still trapped under rubble. Nearly half of those being mourned were children.

Adding to the grief was the understanding that this was the closest thing to a proper funeral most of the victims would receive. “Today we’re symbolically coming together to bury them, because they deserve a sacred burial,” said Vivien Sansour, writer, artist and founder of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library. She addressed the gathering in a voice wearied by unspeakable loss, not just of people but also of a place and the ways of life rooted there, of an entire world. “There is a part of our spirit that is also being killed.”

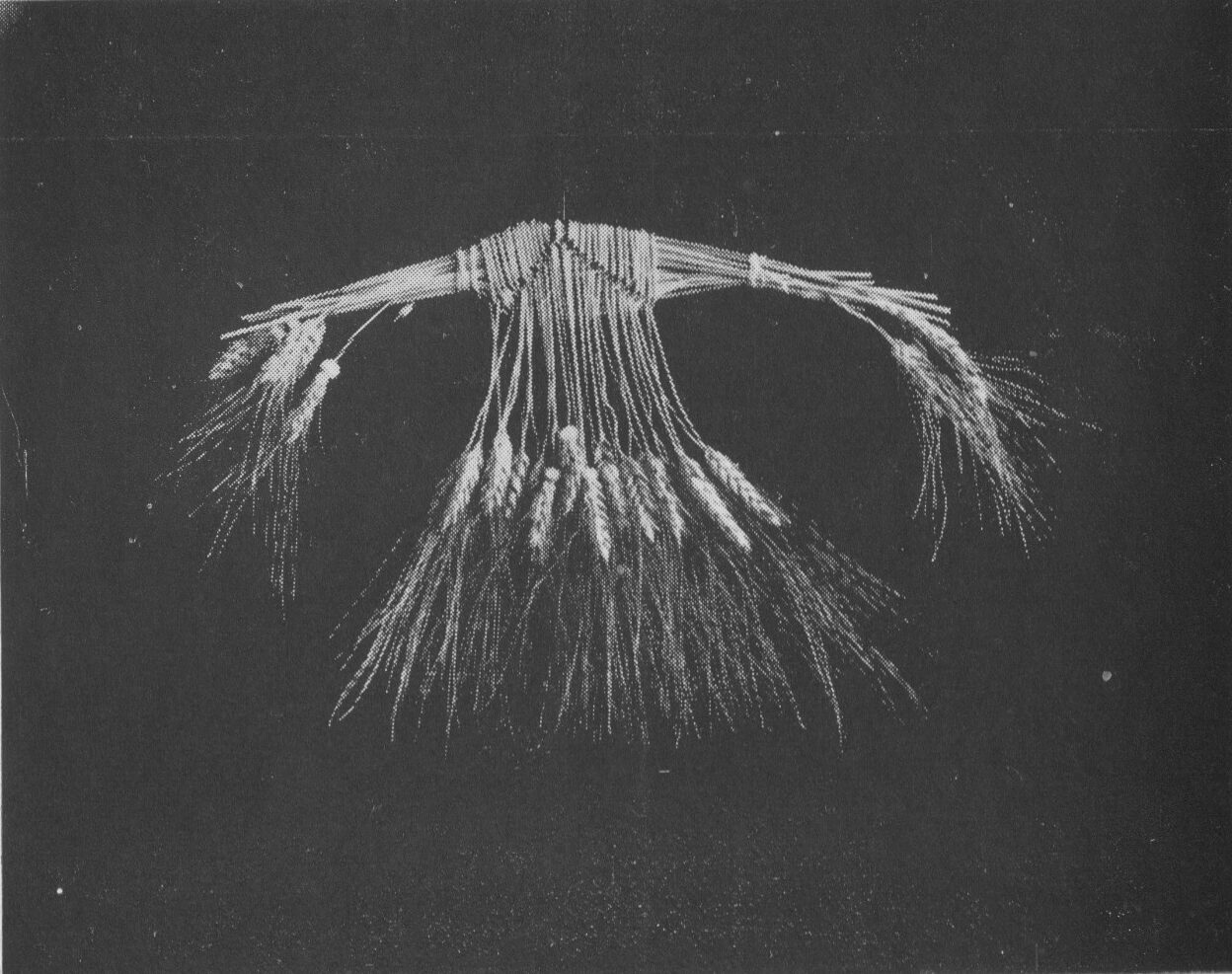

The ceremony concluded with an offering of seeds and cups of soil. Some of the seeds themselves were also Palestinian, recovered and preserved by way of the library Sansour founded in 2014. If there was any hope for life after the catastrophe unfolding so far away, yet so close to heart, it somehow seemed contained within these humble envelopes.

The bombing of Gaza is only the most recent — and most extreme — expression of a decades long project of erasure and displacement, extending not just to the Palestinian people but to their lands, waters, and food, the very roots of identity and ways of life. As settler encroachment intensifies in the West Bank, where Sansour was born and raised, lands are violently seized, centuries-old olive groves destroyed, while denial of agricultural autonomy prohibits traditional farming practices, and increases reliance on commercial seeds.

Vivien Sansour“I have seen seeds make their way out of concrete and I have seen people come out of rubble and I have saved my own seeds in ashes and I have seen life insisting on itself—not because of us but despite us.”

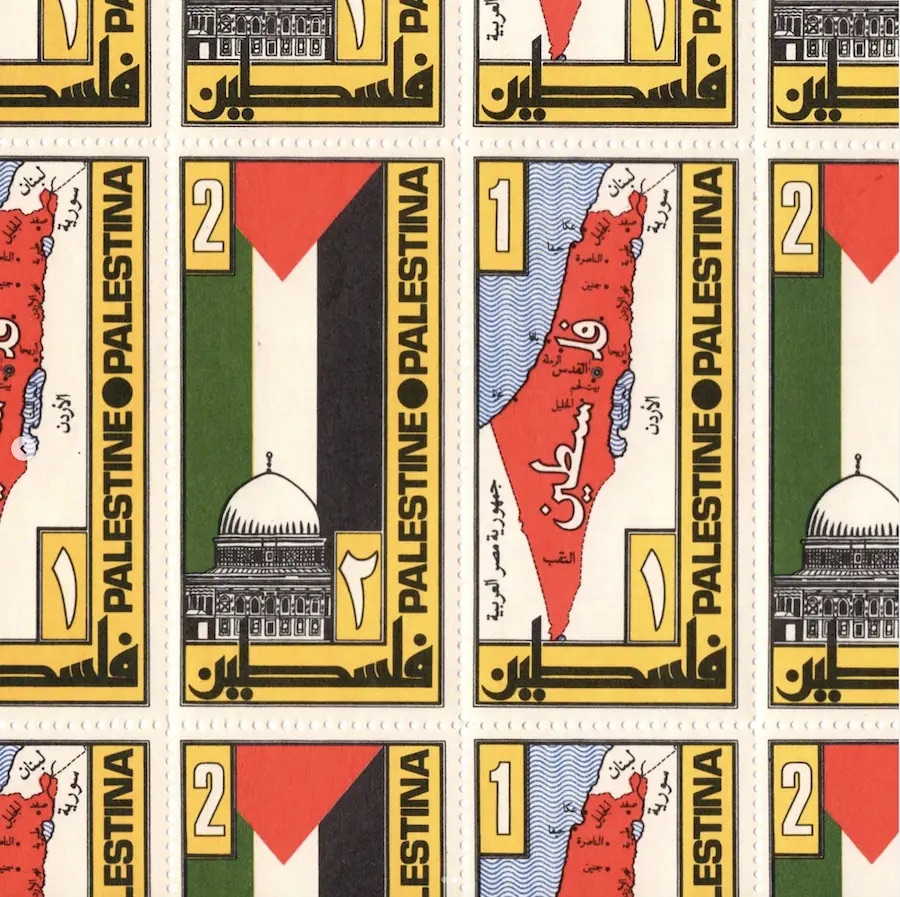

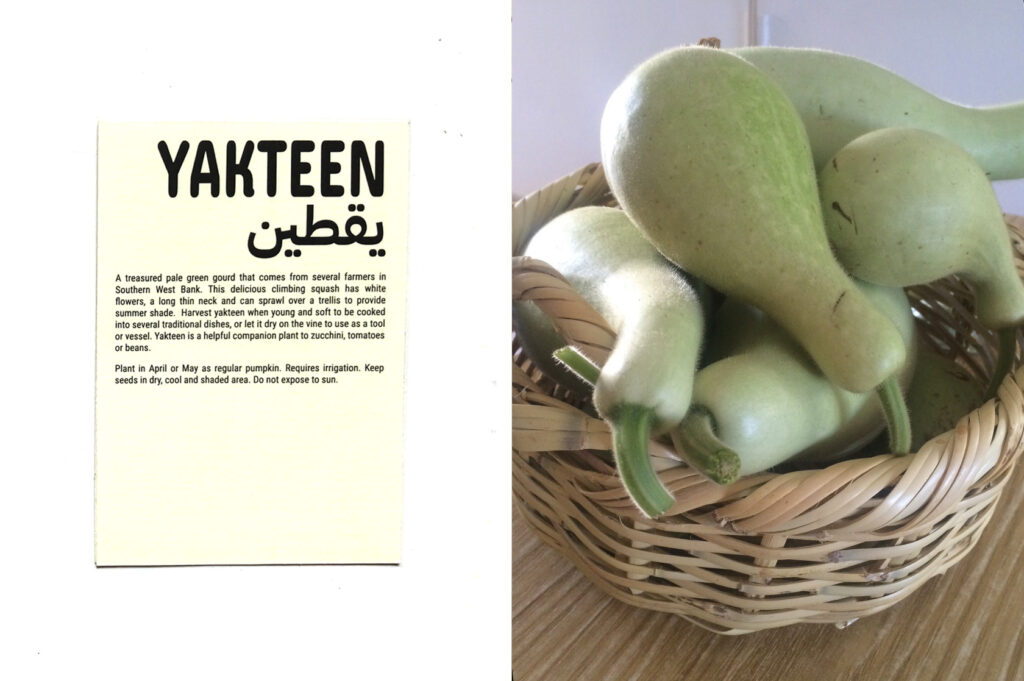

This is the backdrop against which the PHSL was formed—to collect, preserve, distribute, and propagate heirloom seeds that would otherwise be lost to a deliberate process of erasure. In part, it is an effort to preserve regional biodiversity. Many of the seed varieties are ‘baal,’ or rainfed crops. For instance, the famous Jadu’i watermelon, which has become a universal symbol of Palestinian resistance, represent invaluable genetic resilience as the climate changes. But these seeds are also the culmination of centuries of discourse between plant, environment, and farmer. To preserve them in the midst of disaster is to usher cultural memory and tradition through rupture and collapse.

“I think it becomes more urgent that as we’re thinking about saving Palestine, we’re not just talking about saving the people,” Sansour told me over tea prior to the funeral. “There’s a whole ecosystem that comes with it.”

The two of us spoke because I hoped to learn what the weeks of escalating violence in Gaza and the West Bank meant for the work and future of the PHSL. Some of the effects were practical: plans to open an ecological education center and experimental kitchen, for instance, are on hold indefinitely. But the real impact of the violence is more immediate and fundamental. “Even as we’re thinking about our project, which is meant for seed conservation, now we are having to think about how we’re going to feed ourselves and our people,” Sansour said. “Even having the security of a plot of land where we can grow—not even for seed, just for food—is highly uncertain.”

“What’s happening in Palestine mirrors what’s happening in traditional farming cultures around the world, but it’s heightened in the West Bank because of the occupation, and corporatization of agriculture,” said Nathan Kleinman, co-founder of the Experimental Farm Network, one of various partners helping to preserve, grow, and distribute PHSL seeds beyond their native soils. “We’re very hopeful that Palestinian people will be able to grow these in Palestine for the long term, but when we look around at what is happening, it’s very easy to see that these seeds are going to have to be preserved outside of the region, because there’s really horrific violence happening, and depopulation, ethnic cleansing, genocide, and people are not going to be able to grow there, at least in the short term.”

The PHSL exists among many locations and projects around the world, but its official home is in the village of Battir, west of Bethlehem, a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site host to rich agricultural tradition. Established around bubbling springs and an ancient system of irrigation terraces, for many years Battir has faced intensifying pressure of settlement expansion onto the rocky hilltop around which it is built.

“It’s becoming increasingly difficult to access lands our lands, and it’s been more and more difficult for farmers just to maintain economically,” said Sansour. “One of the saddest moments happened a year and a half ago, when one of the farmers that I worked very closely with came over with a trunk full of seeds and said, ‘take them. I can’t do this anymore.’ He has been cornered, like most people, into having to make difficult choices, because he has no access to his land anymore.”

In a small room in Battir, there are shelves bearing jars of seeds and a modest library of educational books. Most of the seeds came by way of conversation with farmers and elders, whose memory of traditional foods inspire the PHSL’s process of seed identification, location, and preservation. The jars are labeled with the name of the seed varieties, and sometimes the human who brought them. Besides storage, just as crucial for preservation is to distribute the seeds to anyone willing to cultivate and perpetuate them. As to where in the world they have wound up, Sansour cannot be sure. “We don’t have forms for people to fill, anyone can pick up anything,” she said. “I like that, because it really symbolizes the freedom we hope to achieve ourselves. If we can’t fly, our seeds are flying.”

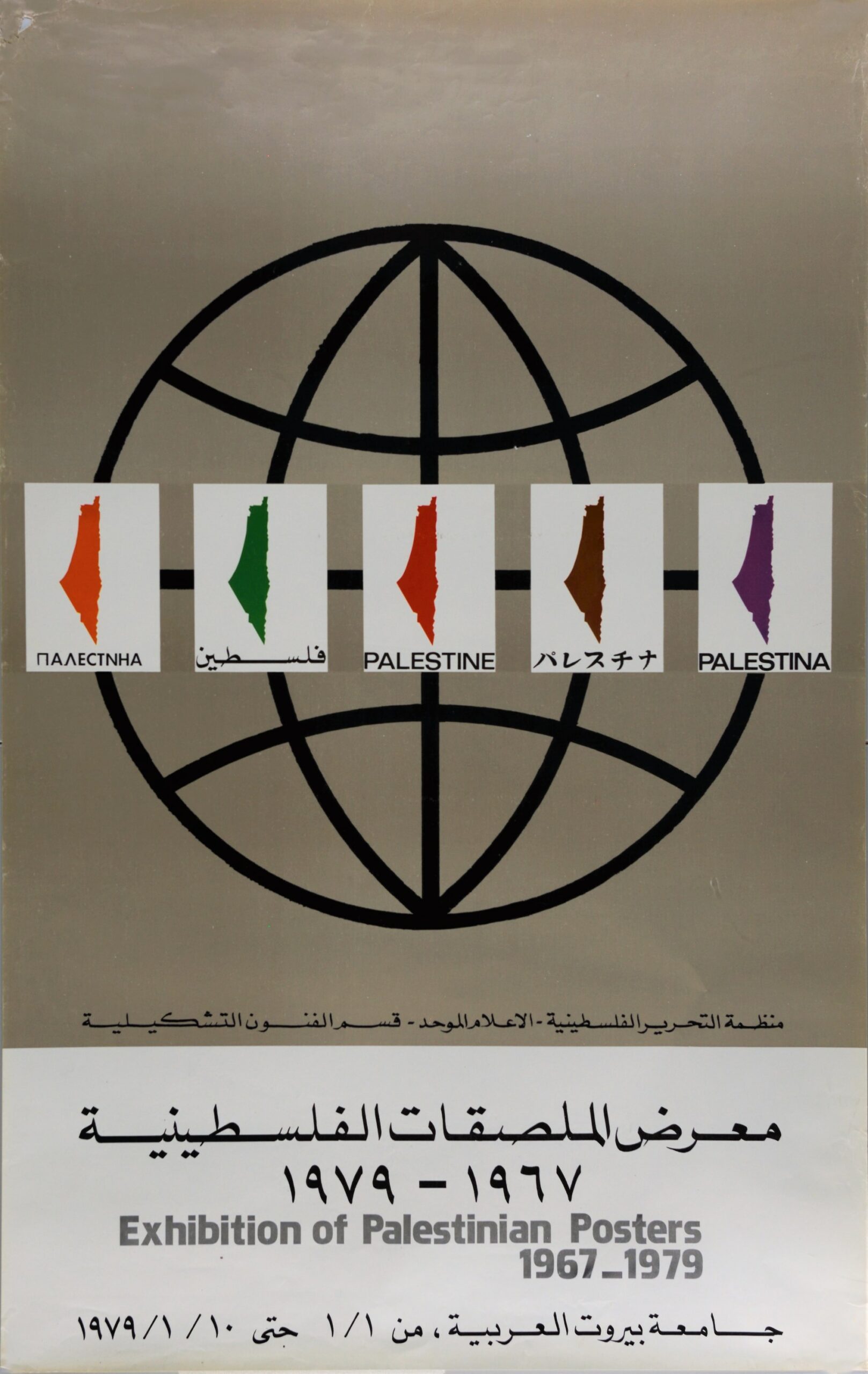

The violence perpetrated against Palestinians represents not just the destruction of human and more-than-human life, of entire bloodlines, but of ways of being and of knowing. It also reflects the inevitable collapse of industrialized empire, and the broader complex of humanitarian and environmental crises that share the same roots. “The world is in hospice, the whole world,” said Sansour. “Palestine is offering the world a mirror to the urgency that everybody’s been ignoring.”

There is an act of resistance inherent in preserving a seed: against scarcity, entropy, homogenization, even colonization. Even as the world crumbles in the here and now, the seeds that make it through the breach will determine the shape of what emerges from the ruins. In a painfully illustrative metaphor, Sansour noted that many of the seeds she receives from elders are gray, owing to an ancient tradition of preserving them in ash. Indeed, as a people’s world is bombed and burned in an effort to erase it, if there is any hope to be found, it may be In the fact that people and seeds alike have passed together before through the ends of worlds and into the beginnings of new ones.

“When there’s a fire, through their roots trees send signals to other trees that fire is coming,” she said. “When the trees know they’re going to die, they start to produce seed like crazy. You’re dying, so you start producing seeds.”