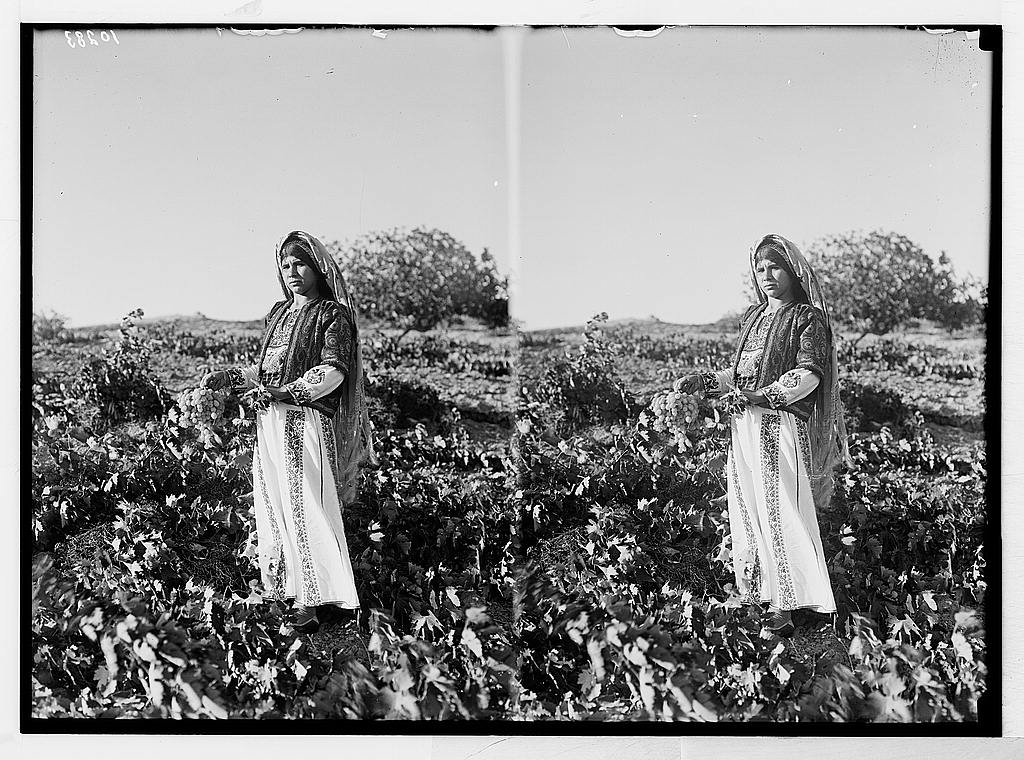

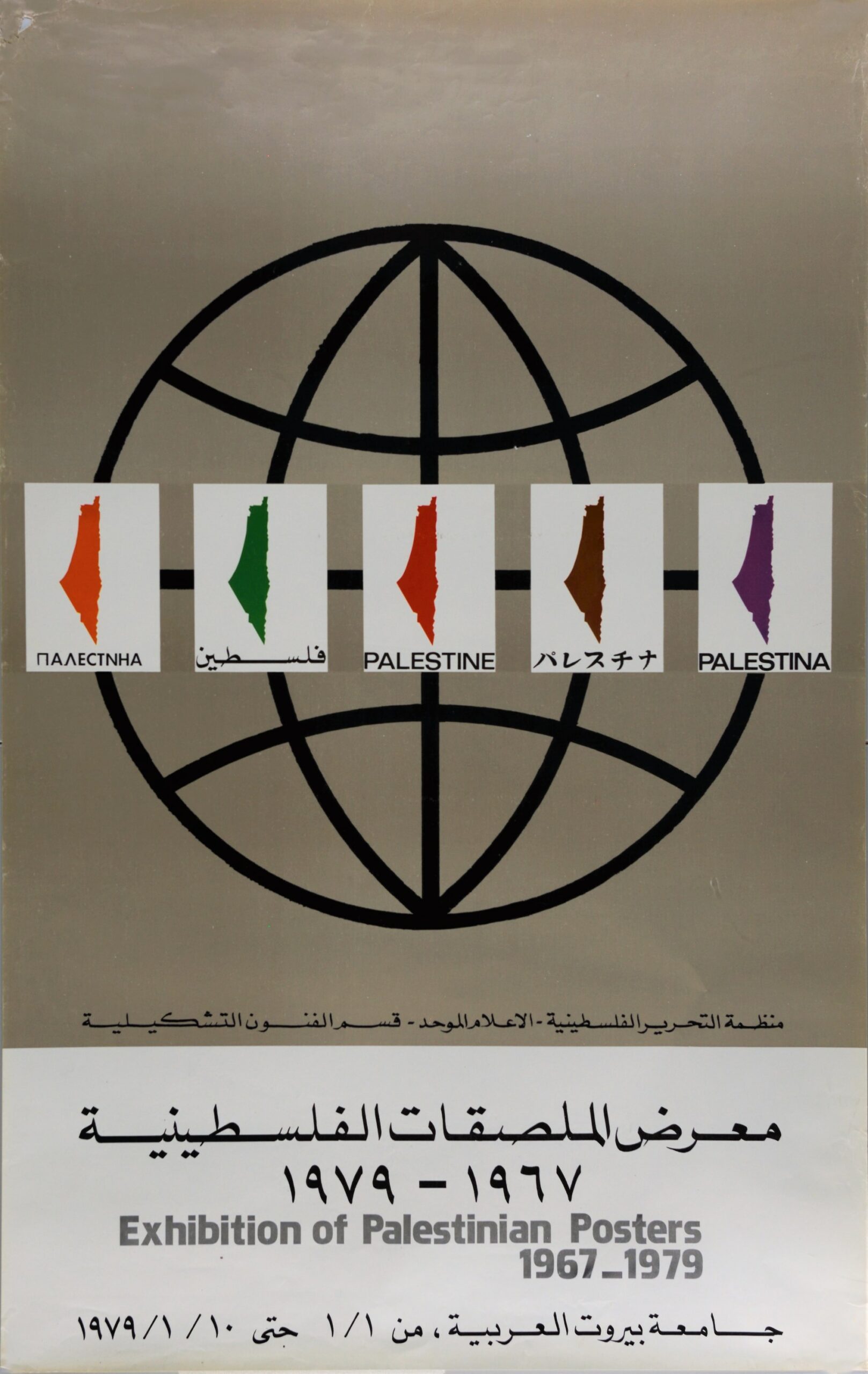

Established in 2015 by Sari Khoury, Philokalia is a wine project in Bethlehem focusing on indigenous Palestinian grape varietals. Drawing from a background in architecture, Khoury’s approach to winemaking, in collaboration with partner Vicky Sahagian, has a reputation for being aesthetically attuned and provocative. Provocative, in the wine and winemaking process and expression of the compromise, oppression, and traditional and ecological realities of occupied Palestine alongside a deep historical consideration of the region. The region is one of the oldest wine producing regions on the planet with a profound and nuanced history of agriculture, tourism, and religion. A history which has been effectively flattened in recent times. In winemaking this is apparent in the relatively recent importation of international (i.e. European) varietals, and with them, the wine grape pest phylloxera followed by the introduction of phylloxera resistant American grape rootstock. Indigenous and autochthonous varieties of grapes and their corresponding traditions of agriculture and maintenance, have dwindled in the region. What little remains is at risk of appropriation by an occupying force interested in naturalizing its presence through agricultural participation. Meanwhile, increasing day-to-day pressures on Palestinians can result in an increasingly survival-based and reactionary approach to agriculture. This combination perpetuates a systematic alienation from both historic modes of production and the perpetuation of living traditions.

In speaking with Khoury, we discussed tradition and craft, the sense-able (and the not so sense-able), and limitations of both material and knowledge.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Adriana Gallo:

How does this project, Philokalia, relate or depart from your architecture and design practices? Do you feel that there are methodological throughlines between the two?

Sari Khoury:

I would say Philokalia is 100%, a design project, not a wine project.

I came about wine by chance, it was introduced to me while I was working in Paris by a Palestinian artist, Nasser Soumi, who was quite a wine connoisseur, and who has about forty plus years of research on Palestinian wine history. I was just amazed at how colorful this history was in comparison to the grayness of the present moment. And so [wine] became a vehicle to take design ideas that you can’t really execute in an architectural context. Because here, like anywhere, architecture depends on the collaboration of the client – otherwise known as patron, right?- craftsmen, economy, materials, laws.

In general, for me, architecture is meaningful here in Palestine, this country needs it. So I’m trying to do something here in this country. I decided to take the same ideas into a realm that’s little explored here, which was wine. [I had] no real starting point, other than knowing that in ancient history, it was a fabulous wine that was exported to ancient Egypt and other parts from the Bethlehem area and Jerusalem. This area—the southern part of the West Bank, from Bethlehem, and Hebron— is known for grapes. I just decided to start to explore, but I don’t have a wine background or an agricultural background. I have a design background and an MBA. I thank God for the MBA thing, because architects sometimes think the world is flat, and their ideas are the center of the universe.

AG:

As if it’s all a rendering and you can just sort of insert whatever you want.

SK:

Exactly. So I would say Philokalia is a way to understand the context in which I operate through a business and design mind. And then to create a mechanism for production: that whole sequence that also gets lost in difficult circumstances where people lose a sense of process. So let’s say if we were in some university setting right now it’s very easy to take an idea from conception to realization. People have a sense of process. You can discuss concepts, you can discuss resources, and you can fine tune and you know, get to where you want you want to get. People here [in Palestine] have shifted towards the end goal always because of the short-term survival thinking. So I derive lessons from my design background to create that sense of process. I’m interested in excellence as far as design is concerned. The economy of Palestine is such that you cannot depend on quantity and low prices, things are very expensive to deal with in this country. So your only avenue is quality. [My practice] is essentially reading signs in the environment and then trying to create a sense of process through design though, obviously, the aesthetics are from the gustative point of view, the one angle that architecture just doesn’t have, it’s unique to wine or food.

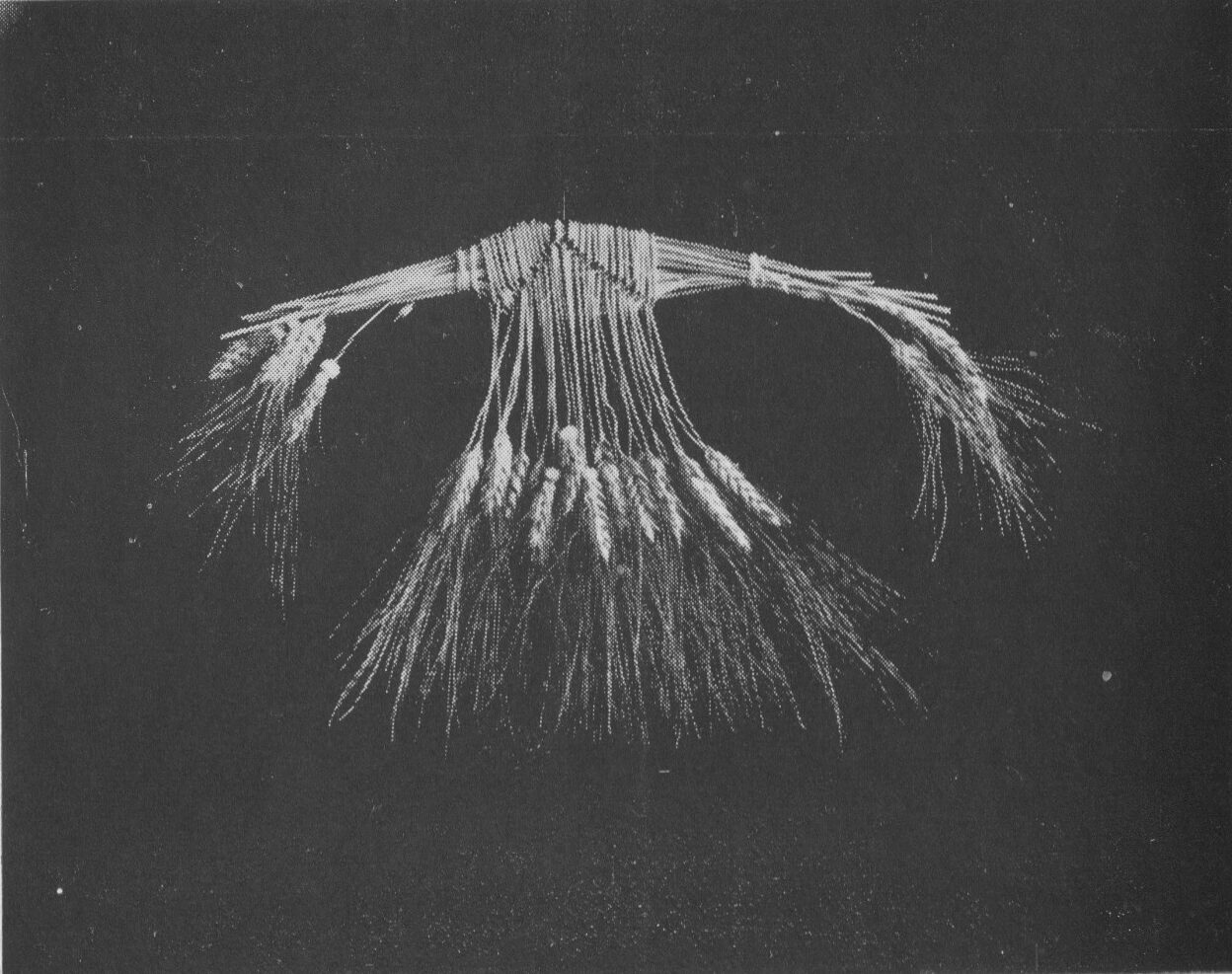

Say, for example, I want to plan out a plot for planting. The architect, or surveyor comes to mind in thinking of different ways to organize the site with knowledge of wine, but also thinking of architectural planning, space…and then I want to work with amphoras as the ancient Canaanites. So the exploration of clay. Testing and just refining your tool, right? So yeah, my approach is as a designer, not as a winemaker, and even as some of the wines improve, like a particular cuvée improves over time, I find that I start to understand the role of each grape, even in a visual design sense. For example, one wine, Grapes of Wrath, somebody would say, you know, some tannin here, some floral aromatics here, some mid body here. And I start to think, No, this grape gives some spine, some structural element. I could think of it more like a flower, let’s say. So every year since I’ve understood that structure, I say, tasting the grape, Maybe it’s a flower that could be with a very long stem this year. Or just celebrate a very broad flower, depending on the quality of the harvest. But then that said, the visual interpretation of what I’m trying to do that comes from a design background, I think

AG:

I wonder the extent to which you consider ‘tradition’ in winemaking, architecture, or design within your work? I think about it [tradition] in a very etymological sense. So, inherent to the word is the latin tradere meaning ‘handing over’ so rather than tradition being sort of this passive or past static thing, it’s a sequence or handing over. Not even necessarily linearly, it could be exponential, it could fan out.

SK:

I think it is sort of a subconscious driver, right? Because Philokalia’s insights are inspired by ancient tradition. Wine was first made here some ten thousand years ago by the Natufian civilization, who also domesticated the grape vine, the olive tree and wheat. So you try to go back to some element, way back in the tradition, and you try to tell people today who have some traditions that are more recent, that this is what we’re about, and they ignore it. But then you have to dig back into the tradition to find the essence, the living matter. Because, finally, the tradition of tomorrow is what’s being created today, in some sense. And I think there is a personal interest for me to create some shifts in the traditions of today, for better traditions tomorrow whether they’re intellectual or practical. There’s also that sense of continuity that, you know, we tend to look at our history, partly because of the politics as, let’s say, Muslims and Christians, and then there are Jews, right. And it ignores the place with ten thousand years also of urban history.

AG:

Sure, of course. Built and continuous history.

SK:

By looking back maybe two or three layers deeper into the traditions of the land you find more windows to create some space and more options. And [in this way] it’s very much connected to agriculture. But, specifically for me the traditional dimension that I want to challenge and maybe propose a different model to is how we approach work, how we think about things, how we look at things that I think should be changed and how we should acquire a new tradition. And the deeper I look back into the history, the more I’m amazed by the genius of these civilizations, a people with little material resources. Today somebody would score a wine 100 points, say, a wine critic. But if you give somebody 100 points out of 100, what are you giving to the guy who actually invented wine? We’re not leaving enough space to consider the original innovation. And I try to tap into that mindset that went into wine and went into domestication of certain plants. I ask farmers, You’ve been planting grapes for so many thousands of years. But you’ve only had pesticide for fifty years in the West Bank since 1967, essentially. And so what were you doing for, you know, all these thousands of years minus fifty? And they start to show me some wild plants that they infuse in water and spray the plants with. Those have potential for the highest organic standard in the world for grapevine treatment. And then you’re struck by the sense of observation, that somebody was able to spot something in the environment that can be a tool to treat a difficulty and another aspect in that same environment, through observation, through experimentation, through exploration. That is that spirit of genius that was part of the tradition, obviously, because there’s evidence of it, and that is being lost. So I think I want to reinstate that as part of the tradition.

AG:

There is then, perhaps, the appropriative potential of the methods of older traditions, the methods of observation, of relationships between plants or environment. I wonder if you think there’s something inherent to agriculture or culinary craft, or even wine traditions that allow for that particular mode of interfacing with a historic or ancient register? The way that you’re describing it collapses the timeline in a very specific way.

SK:

Oh, very much, you know, we still refer to in Palestine – although most people don’t refer to their Canaanite traditions – but we refer to certain crops like quality grapes, and certainly all olive, all figs, pomegranates as Ba’al crop. Ba’al is the ancient Canaanite guide of fertility, and here we’re referring essentially to rain-fed crops. We prize those over irrigated crops because it’s known there is more concentration of flavors, the plant is more resistant to drought, etc. So we’re always referring to Ba’al farming. And the Dapke, our traditional dance, is the dance to sort of encourage Ba’al to give us some rain and even arouse working in the vineyard. Once I was really tired and stomping my feet a little bit like the Dapke and I found that that stomping actually relieved so much of the pain and invigorated the body again, just by maybe tapping the nerve endings on your foot. I think the guy who invented Dapke was just really tired working in the field.

I’ve been asked quite a bit about Palestine’s wine history. So you have, let’s say, eight thousand years of history and then with the advent of Islam, you know, wine and wine production was slowly phased out. But actually, then the continuation of wine in the rest of the world, Europe, and even up to the 1700s when it went to the US, was the work of the Church, which is, in essence, a Palestinian export. And I think that the French, for example…the direction they took with wine is that transcendental direction that is very much related to the church tradition, the church philosophy, right? Christian philosophy. And I cannot say I’m not inspired by that spirit of operation. You’re in a certain condition that you want to transcend, and elevate, and improve and keep going up. And it has its parallel in the Arabic Islamic tradition of alchemy. You take a base condition and you try to elevate it into something valuable. I would say there are things in the tradition that are inspiring in the environment but they’re not covering the tangibles. And then there are the tangibles in the field, as well, whether it’s the plants themselves, how farmers work or treatment by herbs.

AG:

I suppose this is a more practical question, but can you describe specifically some of the tools or methods that you use that are either historically inspired or completely modern and contemporary? I’m curious what the practical examples of some of those tools or methods might be.

SK:

So I think it starts off in the vineyard and having to understand what farmers are doing there. I try to spend a lot of time with these old farmers that have this tremendous sensibility with working in the field, the climate, the variations between seasons. They’re not, you know, academically trained, they’re just rooted in a place. And I try to sift through the, let’s say, the compromised practices that they’ve had to do in more recent times and try to look deeper at the origins. So, for example pruning and the structure of the vine. In modern winemaking, it’s on a trellis, it’s almost two dimensional, unless it’s a much more arid climate where it’s just a three dimensional bush. Here, we use this bush trellis, it’s on a post and in fact is a small tree. Tillage obviously was also a Canaanite invention and how they know how to time the tillage is fascinating. I was reading something from Bordeaux recently, where they discovered at some point before harvest that to do one round of tillage is really good and invigorates the grapes. I went and asked the farmers about it: I read this that they use in France and they all started to laugh.

AG:

Like, of course, yes

SK:

Like, yes. And I forget the term in English, but when the grapes are very green, very young and green. What’s the word for this?

AG:

Underripe I suppose it would be? That doesn’t seem precise though.

SK:

Yeah, so we have a word for it in Arabic that specifically describes this moment in the grape’s evolution, and we call it the tillage of ‘that word’.

AG:

Ah, timed by the grape so the temporal structure is specific to the plant as opposed to the calendar.

SK:

Yeah, that little push before it starts to really ripen. So they start to laugh, Yeah, we used to do that many years ago. But then for the pruning specifically, because it’s like this little tree, we do several passes between, let’s say now and harvest time. And it’s not a one-time thing like most modern winemaking, it’s really a dialogue with the grapevine throughout the season. You’re always going back and having this discussion, it’s not a one time abrupt act. And that’s very useful to deal with the seasons and to get a quality crop and an expression of that year. But it also creates a set of sensibilities that are very important to know what state of mind you should be in, to continue to produce. But the actual tools in the vineyard are some pruning scissors, a donkey, and a little carriage device behind the donkey. Nothing too serious. In the cellar also, I’m very, very basic: a few tanks, some amphoras that I made. Nothing out of the ordinary as far as the tools. I think the clay composition is out of the ordinary but beyond that…

AG:

In what way?

SK:

Well, I had the good fortune to do five years of ceramic training while at Virginia Tech and came in very handy. So we had these old ancient Canaanite black jars for wine. And I was trying to discover what these black jars are about. And why black. And so I sort of extended my research into clay and came up with my own composition for this clay jar that fits my work. And well, it just has quite a unique expression. And I say they’re out of the ordinary, maybe, or like ‘excellent’ jars, because I’ve tasted many wines around the world made in jars and most of them produce fascinating results for white grapes. The expression I think is more profound for white grapes than red grapes, on average. And for these amphoras, that I’m testing now on a new wine, I found a tremendous potential on either grape but especially a red grape. Aromas and wine tend to be linear and this [the clay] integrates the aromas together as would be like a perfume. So well-knit. They just come at you at once in a unison, which is tremendous. And it develops some rather wide and profound tannins in the amphora, even more than oak barrels, which are full of tannin. And by chance, I made them only to fit a very small space, so they were like 65 liter jars. And apparently that’s the same size as the jars of Abydos – the Canaanite jars that were buried in the tombs of the pharaohs, which are now in the Louvre Museum. And so I think that’s maybe one special tool, but the rest are very basic, almost primitive.

AG:

You’re speaking about maybe these different temporal scales. I’m also wondering about site specificity. It’s something I think about a great deal in terms of materials in my work, but I’m wondering about in relation to your architectural background. I’ve been thinking a great deal about Aldo Rossi’s term locus and specifically its relationship to the genius loci which are ancient site- or object- specific spirits or divinities. So eventually they would be converted to Catholic saints and appropriated in service of the Catholic project. And I wonder, in winemaking, or architecture, or your practice just uniformly, the extent to which you consider site-specificity and how much that’s imbued with soul or spirit or essence? How do you interface with site?

SK:

Well, in terms of architecture, it’s 100% engagement with the site. It’s very context-specific. I start off with each project, very much wanting to read the place or [understand] the movement around it. Its value beyond the client’s project: what did it mean for the city, or that neighborhood around it? So in a sense, trying to kind of discover what is the spirit of the place. And for me, as far as the architecture is concerned, the site is an integral fundamental element. And there is no reason for architecture without it. But in wine, it’s a lot more ambiguous.

In Arabic we say there are traditions that the land variations are measured by shi-ber, shi-ber is the distance between your thumb and your pinkie. And farmers are always saying there are variations in the expression of the soil in such minute distances. And that’s true, I harvest grapes from different plots, and I see different expressions. But then, as the wine is evolving, it takes you through so many different things that there’s that magic there that you can’t define. And so it’s the exact opposite, you’re completely helpless, you don’t control it, there’s very little for you to read. And you depend on nature doing its magic a little bit. So it’s like, you get a sense of place, and a sense of process that complements that place up to a certain point, and then the wine is laid for rest. And then it comes back again, a completely different person. Right? Like something reborn. So, I would say the concept [of site specificity] applies maybe to the first part. The rest and why is its own animal, and there is a kind of resurrection later to create something completely new.

AG:

I think that in the process of metamorphosis there is that necessary obfuscation. For that to occur, there needs to be something contained or obscured or hidden. I’ve been thinking a great deal about terroir and territory outside of wine specifically. It’s sort of a borrowed interest from wine. And I’m wondering how you engage with terroir? And I suppose terroir, or territorialization, even as a tool to naturalize an individual or perhaps in the case of Palestine, an occupying force’s relationship to the land? There’s also this sort of interesting strain I’m seeing in the US, at least of terroir, skepticism or skepticism, as to the influence of landscape on that final product. So I’m wondering if you can speak through your conception of terroir beyond the conventional wine definition?

SK:

You know, the concept of terroir, in modern winemaking, is defined by the French tradition of winemaking for the last two/three hundred years. So they’ve had a long time to come to their own definition. And I think it’s too soon for someone like myself to give a definition that is fitting to me. At the same time, I don’t need to accept somebody else’s definition because that definition becomes the reference in discussion. And I reject that wholeheartedly. I’m happy to learn from the French, but it’s not for them to define, you know, the whole. Because the thing is, I understand the skepticism about it. It’s because it’s become used as a kind of exclusive tool: like some winery has some “fascinating terroir”, as if nobody else has it.

AG:

Or you’ve purchased a very interesting site…

SK:

But actually, if you have the right climatic and soil conditions, a grape will grow and the expression of that grape will obviously be different from one place to another, or maybe better from one place to another. But from my observation in this process, sometimes I would take a grape from a less than ideal plot of land. For some reason, I couldn’t access one plot that I was always happy about working with and I’d end up with another spot. But I found that I can still produce an excellent wine with it. But I have to be flexible to know how to read it differently, read the grapes differently. And try to create a complementary expression in the winemaking that goes along with it. So terroir is a beginning point. But the whole process, everything has an input throughout the whole process of winemaking. [Terroir] sells nicely, maybe. But I think that it’s working with the land, knowing how to work versus just implementing standard practices, that becomes the obstacle. But as for a definition of my own, I don’t have any yet. That’s too soon. But I would say that I see impact of every step of the process. And that includes the state of mind, the refinement that you pursue, the working process, and reading the grapes year in year out. It can make a whole difference.

AG:

I know you don’t work with international varietals in general, which is not really the same thing as terroir, right? That’s a different sort of layer of selection that you’re making. Do you feel that because you’ve elected to organize your palette in a certain way, it allows you greater flexibility in the product? Or does it allow you to say something more specific with the product?

SK:

Yes, for sure. I mean, I think that going back to the design creative interest. What’s the creative exploration that I can really go through if I create another great wine from a well known variety, let’s say like Merlot, or Syrah? There’s also no market value for another great wine of these grapes coming out of this area. And at the same time, I think every great wine culture started off with this relationship between local wine, local cuisine, and local climate. So I’m also trying to explore the possibility of remaking a local wine culture, establish the fundamentals of an industry. To work with these international varietals requires irrigation mainly, and we as Palestinians don’t have access to irrigation water, we have to depend on rainwater. So you understand the holistic set of circumstances and ideas lead me only in one direction which is to explore the native of grapes. And then you have to give that grape a chance to give its own expression. Wine tasters use an aroma wheel that has documentation of different fruits and berries and spices and elements that you would find in a wine. I found that so restrictive because the same guy Nasser Soumi, who got me into wine came to visit me in Palestine. And he tasted the wine. And then he says, And I spot something here in the wine on the nose that is a plant I haven’t seen for 50 years, and I’m sure you Sari have no idea what it is. And I spot it in the wine. And I’m like What is it? and it’s called Mandragora, Mandrake I think in English. And I’m like, What’s this Mandragora? and he was describing this plant that has these really yellow fruit, smells very tropical, and has broad leaves, like almost tobacco leaves. And I started to read about this fascinating mythical plant. And I went back to the old farmers on the vineyards saying, like, This man spots this aroma in the wine. Is there any Mandragora here in the vineyards? They say Yeah, sure. They’re all over the place. Here. Let me show you. And I’ve looked past it all this time, I never paid attention. I’m looking at the same site now for almost ten years and I see how much I was not able to see in the beginning. Every year I’m able to see more and more. But I thought, That man spotted Mandragora in the wine, not having ever visited the site, and I am sure no wine critic in the world, bar none, would be able to spot that fruit in the glass. So what you say about expanding that palette or broadening the references, the possibilities? It’s already happening. I just want to let it be, and then maybe we’ll discover more things with time.

AG:

In general, the project seems to be this particular manifestation of history, ecology, craft, and sort of grappling with what it means to interpret a territory through taste, smell and texture. I think perfume is actually an incredible craft reference point. It does the exact same thing where you’re dealing with composing a sometimes naturalistic experience from synthetics, or a mix of synthetics and naturals. The sort of mix of urban/rural, constructed/natural.

SK:

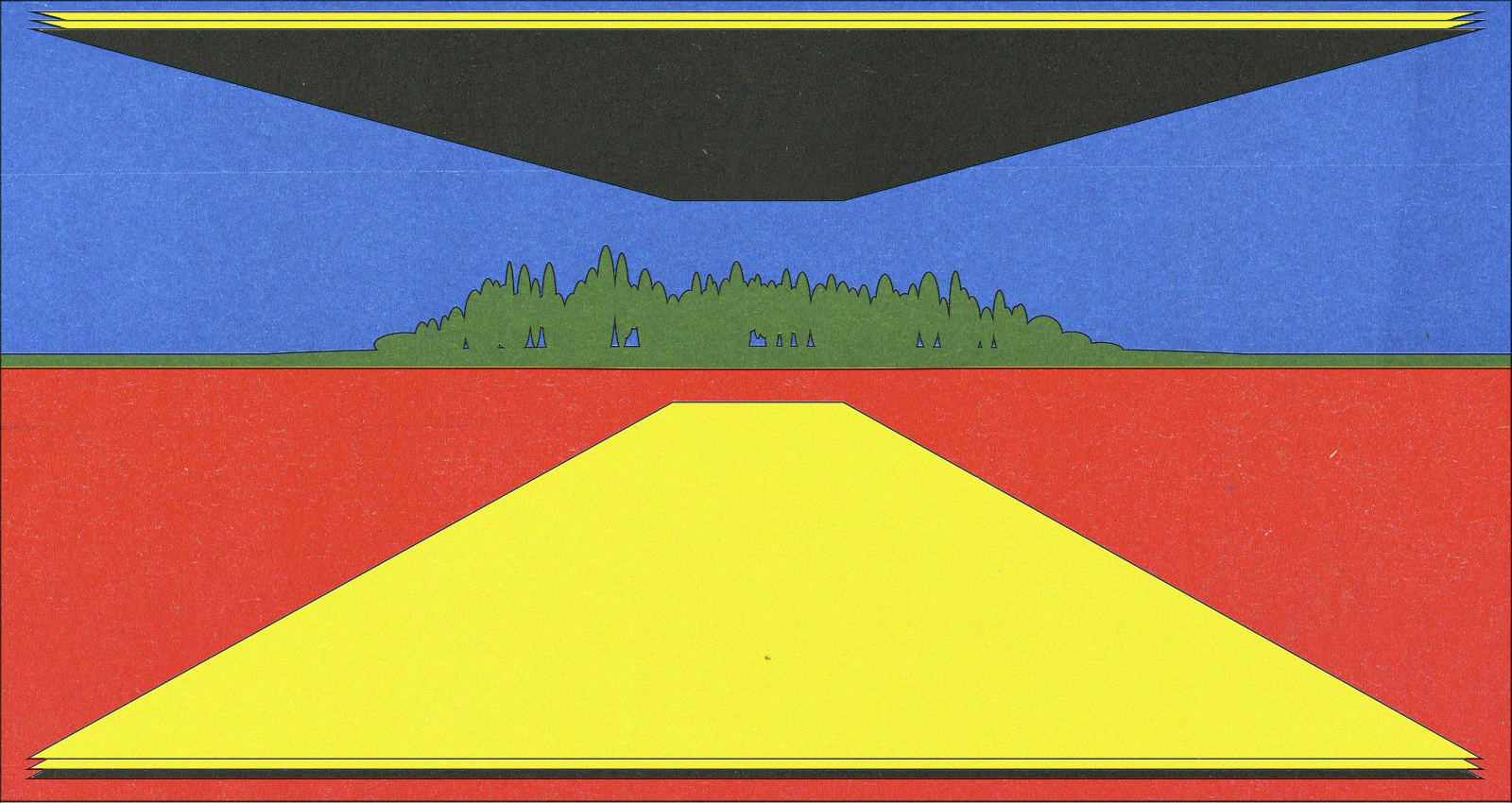

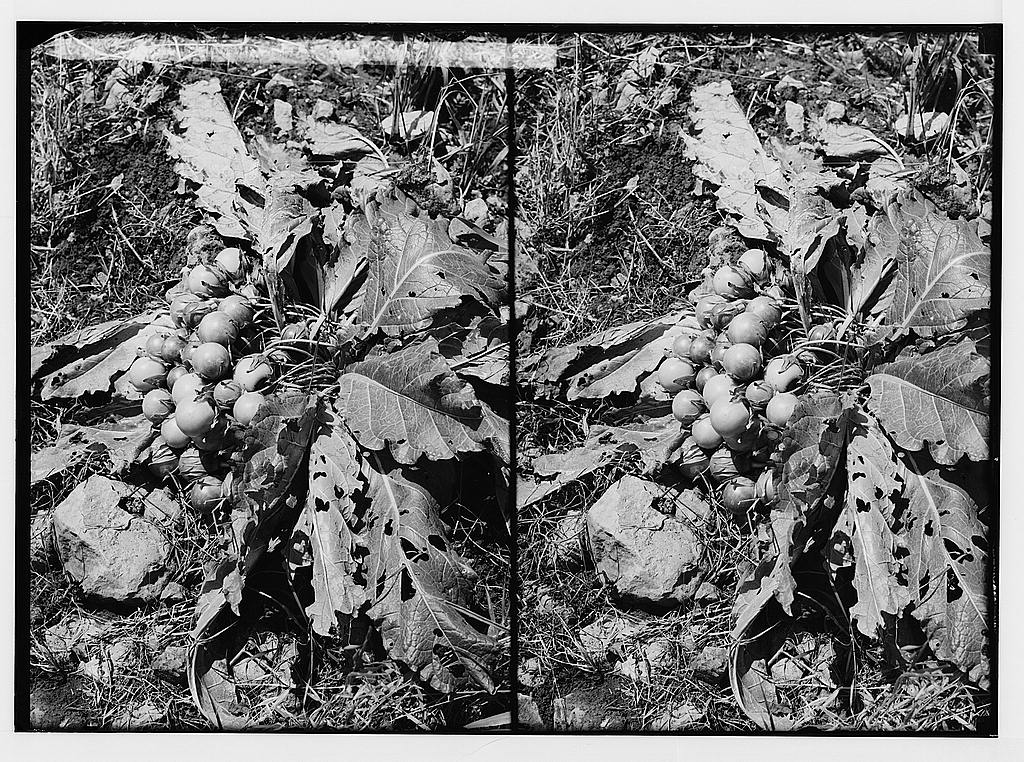

You mentioned Grapes of Wrath, which is our more well known cuvée. I was walking in the vineyard and I became very close with these farmers, we became almost like family. But these are the types of people that don’t reveal all their secrets from day one. And we’re walking around, it’s around this time of year where there’s still just some gray branches. There’s no buds, no leaves, nothing. And I saw some vine branches coming out in between some rocks. And I was asking the farmer what happened here. He was showing me how the [Israeli] army destroyed part of the vineyard of some ninety-plus year old grapes to make a road for a settlement. And they crushed them with massive boulders up to two meters in height and paved the road. And these branches were sticking out from the rocks on the side. And I said, you know, it’s kind of a black and white photograph where gray branches are on gray rock. And I said Do these grapes produce crop? And he was like, Yeah they produce some. So I said I’d like see what I can do with it. And then here there was a frost occurring. So the vines around it actually had no crop. But these stones maintain some heat and so I was actually stuck only with those.

AG:

So they’re insulated.

SK:

And I produced the wine that I called Grapes of Wrath, and it had a double meaning for me. The first meaning was very much in the spirit of John Steinbeck’s book, which talks about traveling out west for the Gold Rush. There they discovered the deception of the environment, right? And for me, as a Palestinian having lived many years overseas, you come back and you’re naive, and you’re caffeinated, and you’re going to produce something in Palestine. I was deceived by what I found, you know, in terms of lack of my own skill, in terms of the complications, in terms of desire to produce and achieve. So there’s that deception that I went through, and there is also that oppression on the landscape. That is, how to say, you know, you and I are not equal Adriana. I’m no less of a person, but we’re not equal, and layers of oppression, they build up also inside of you, or inside a person. And what I was trying to do was tell Palestinians something through that wine, if the wine were to succeed. First of all, I wanted to see if I can take something like dirt or a difficult circumstance and try to create something out of it, is there a possibility? And then if it works, you’re trying to tell people we can take things that look difficult and maybe try to produce something with it. So it was a very personal thing. Yes, there is an occupation. Yes, there is oppression on so many levels, right. Just the control of water is enough of a subject to not even have to go into specifics of agriculture. We don’t control our own water. But then, like I said, the interest starts to pull it out of its context and focus on one aspect of things, which may be far from the beginning [initial] intention, which was a more personal interaction with place and circumstance.

AG:

I understand what you mean. I think there’s that surface-level interpretation, the one that is most useful or lucrative to essentially promote right? But it does divorce it from that site-specificity in so doing.

SK:

The personal human experience with it, that’s going to get sort of sidelined. People promote also in ways that are easier for them to understand. So some things gets lost in translation.

AG:

The nature of the wine itself is that it can communicate all of those things simultaneously, right? The hierarchies are completely different. Maybe there’s a sequence in which you perceive certain relationships, flavors, textures, but the experience is a complete and simultaneous one.

SK:

Like I told you in the beginning, and I’m looking for an avenue for creative self expression, for me to understand, grow, to be able to relate to my environment in a way that makes sense of my existence. And this was just one exercise. Along that path. But with that being said, I also work on what’s in the bottle every year. It [Grapes of Wrath] is the only cuvée that I’ve produced every year with variations of course, since I started Philokalia. I entered it into the San Francisco International Wine Competition last December, and it won a gold medal. Which for me, was very rewarding in the sense that there is that stripping away of the story. It means nothing. No one has time between thousands of wines, anyway, to listen to your story even if they wanted to. There are many wines, numerous wines in the world that have gotten a gold medal in a competition. But I very much doubt any wine has gotten any medal from a vineyard in this physical state. I’m almost sure. So which goes back to that original discussion about alchemy, working with your own society trying to make the best out of things. Look, I took your leftovers that you don’t want to work with. And I tried to make something with it that has some resonance. So the gold is an above-ground not below-ground type of mindset. And so let’s just keep trying and moments like that give me more hope, more inspiration to try more things. It’s hard to go backwards now. And then when you have results that are tangible, then you can go back to your own society and say, Okay, now let’s have a more meaningful discussion, including ones about tradition.