Sasha Fishman’s Brooklyn studio at Smack Mellon feels like a scientist’s laboratory. The shelves are lined with bubbling beakers, in a corner, bags of mycelium grow on a table, and photos of salmon are pinned to the wall.

Constantly experimenting, each one of Sasha’s pieces comes with its own unique process— whether it’s harvesting salmon skin from local hatcheries or collecting chitin from cicada corpses. Inspired by food rituals and food preservation practices, the work navigates the ethics of consumption and desire. Her current exhibition, Resurrectura, showing at Murmurs gallery in Los Angeles, showcases a body of work developed during her MFA at Columbia University. There, she collaborated with chemistry, neuroscience, and architecture labs, expanding her practice across disciplines.

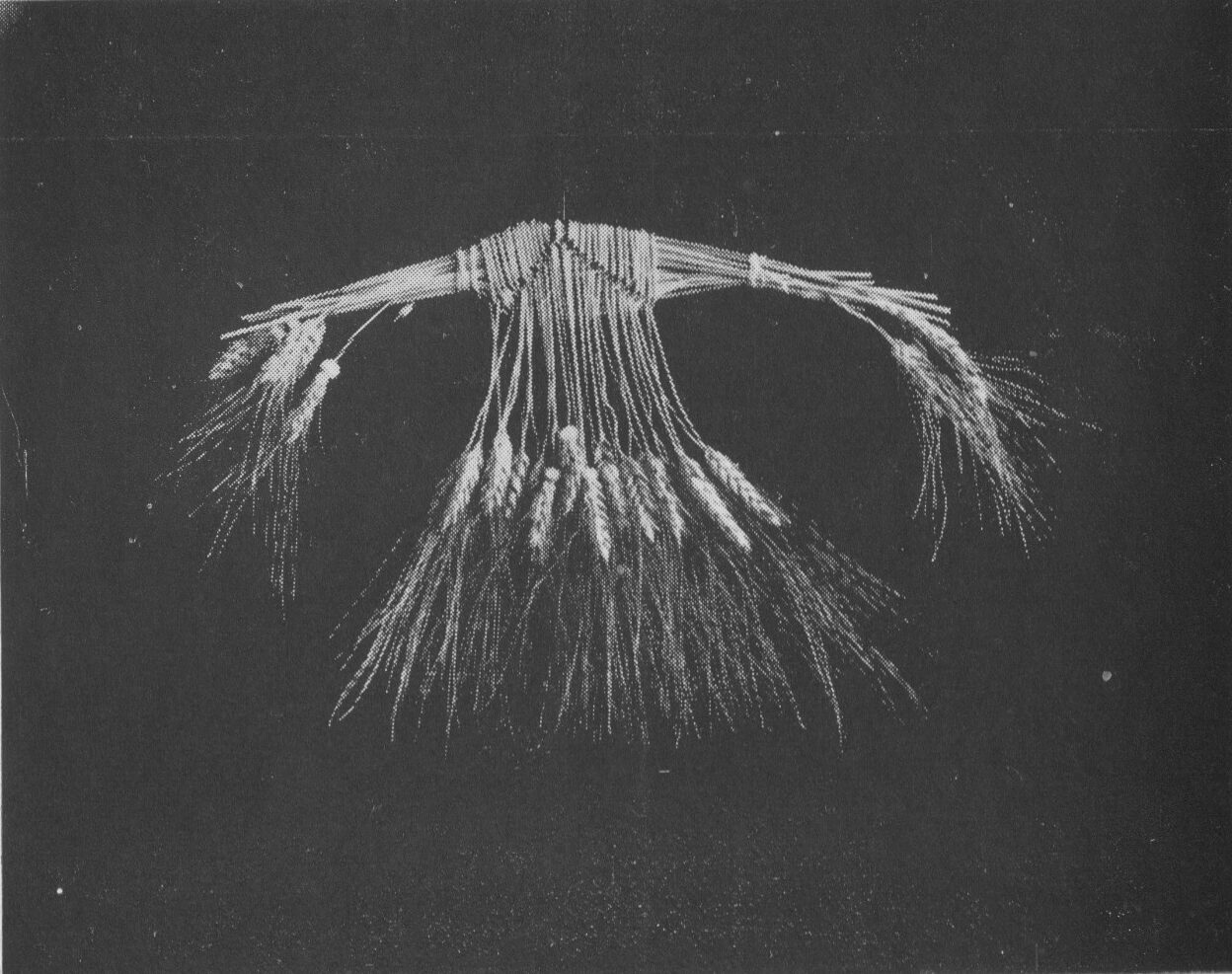

A significant part of Resurrectura emerged from her experience raising hagfish—an eel-like creature that secretes a clear slime as a defense mechanism—in her LA studio. What began as a method for extracting slime to use in her sculptures evolved into a complex affection for the fish themselves.

In our conversation, Sasha reflected on pushing the boundaries between herself and her material, exploring interspecies interaction, and navigating the tension between preservation and ephemerality in her work.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for content and length. Resurrectura is on view at Mumurs until February 23rd, 2025.

Orla Keating-Beer:

Can you tell me a bit about your background? Where did you grow up and how did your practice begin?

Sasha Fishman:

I grew up in Baltimore, Maryland. I was always interested in science and art. I grew up biking and hiking a lot too, but never really connected what they would take me towards. It was the summer after I graduated from undergrad and I didn’t have a studio. I was casting a lot of resin and toxic materials like silicone. Having [the] limitations of only the kitchen and wanting to cast materials was kind of what brought me towards alternative materials.

I ended up seeing these shows in LA at the time. And there was this one show that was by Haena Yoo and Sterling Wells. They had done this installation together with all these food containers that were stacked and you couldn’t tell what was rotten food and what was a bioplastic. It was incredible. It was just so messy and sticky, just this really strange contraption, almost like a hamster cage, but for these foods. [For my practice] bioplastics was just the word I was looking for. That brought me into this space of research [where I was] able to formulate materials myself and have this autonomy over the materials. I was beginning to question the agency between myself, the materials and what the work is.

OKB:

How was your first bioplastic experiment? Do you remember what you made?

SF:

It was gelatin and I thought that I had figured everything out. And actually, my dog ate it.

I had cast them in a pyramid mold, and they were 3D, they were thick [and] they were clear. Everything I was obsessed with at the time was based around clear materials. Clearness has been interesting to me because [with resin] you can almost solidify water or capture something inside of it and hold it there forever. You can never quite get to it again. Because I knew resin was so toxic, I really wanted to find a way to replicate that phenomena with another material that was bio-based that could also disappear later. And then, you can control the timeline a bit more. The first time, I thought I figured it out but then the next day they were warped, moldy and cracking. I really wanted them to stay the way that they had first been. It’s almost like the futility of working with these materials that I’ll never overcome is that they will constantly change. But what’s also really exciting about them is that they’re never fixed and also constantly surprising me. [Bioplastics] really pushed my expectations around material, how it behaves, how it performs, and it’s made me think about my expectations based on commercial materials.

I don’t like to say that biomaterials are the answer because there’s so much more complexity than that. A lot of the work that I make has different timelines in different parts of the work. Different things will definitely degrade sooner. Depending on the environment and how well things are cared for, they can last a long time.It’s really just a matter of if they’re in a more humid environment or if there’s dust or oil degrading the material over time. But I like the idea of the work aging and how that process can encapsulate time.

OKB:

In some ways, the space and its climate and conditions are also your material.

SF:

It definitely is a material. I can tell if it’s more humid or dry because the work will change. The changes will tell me about things I can’t quite detect.

OKB:

Tell me about Resurrectura. How did this show evolve out of previous work?

SF:

All of these works I made when I came to New York [to attend] Columbia. I feel really grateful to have them in LA because a lot of the work began there and they are remnants of my time there. Hearing dryness, longing for wetness, has little images inside of the basin from photographs I took of fires in LA, things drying out and bodies of water. I’ve been thinking about wet and dry intelligence as well as wetness and dryness as a spectrum in relation to hyperobjects, stickiness and change. Living in LA and experiencing these really extreme changes influenced the work.

Also, [another influence was] my time with the hagfish. I was working with them alongside scientists, but then I fell in love with them. And when I would slime them, I would stress them out, so I stopped extracting from them. It was making me think about being able to be an artist and to have this way of working that isn’t linear versus the sciences. At one point, I wanted to be a material scientist because I was developing these materials and wanting so badly to get the right output. They ended up dying and I was really devastated because I wanted to hang out with them more.

OKB:

I was going to ask if they were still with us…

SF:

Well, their bodies are, the physical remnants are. I’ve been interested in the spiritual connotations of flayed skin or preserving a body beyond death—which we rarely see with fish. We let other mammals live on beyond death, and I’m trying to understand why that is. I found this recipe through my research on how to tan fish skin with egg yolk. And I did that with the hagfish skin, after dissecting them to figure out why they had died.

OKB:

In this intimate relationship that you built with the hagfish, did you rethink using animals in your practice? How did it play into this idea of transcorporeality and blurring the boundaries between you and your material?

SF:

I think it’s a question I’ll always have. It’s really my experience with the hagfish that’s really pushed me to keep asking questions like: What does it mean to work with an animal? How do you show the animal within the work? What are the ethics of doing this? Because I fell just so in love with these fish, and I’ll never know what they felt towards me. And that’s okay. I’m more asking the questions around how can we not have expectations around what we received back from animals, but also how can we also give them space? What even is respect towards an animal? And how do we dismantle the hierarchies? It’s been interesting to see people’s reactions. It made me question what the role is of working with an animal scientifically, especially in how scientists have relationships with their animals, especially because they often sacrifice them. There’s a lot of questions that I have around when it is justified. I’ve also been thinking about seafood waste and debris and how I can use these waste products as a material in my work that’s [also] conceptually related to what I’m thinking about. It’s not always a linear thing, but I ended up finding this hatchery upstate that is basically run by the Department of Conservation in New York. It’s just for recreational fishing, which fascinates me because I never considered fishing as an act of conservation. It’s something that has grown to be a much more complex question than just like, is this right or wrong? That’s what’s so exciting about making this work and really digging into the materials and their sources is helpful for understanding the context, social aspects and economies based around them.

OKB:

Are hagfish like eels where [scientists] don’t know how they reproduce?

SF:

Yes. And don’t you think it would be kind of sad once we do figure out how they reproduce? I kind of love the mystery of it. That’s kind of the way I feel about water and biomaterials and just working with animals. I almost don’t want to know, but I also do. That tension really drives me to keep questioning and circling the thing. I think it’s been interesting to also go to spaces outside of the sciences, into agricultural spaces. At the salmon hatchery, seeing their relationships with the fish, it’s really intense. They basically cut open the bellies of the salmon, take all the eggs out, and then they inseminate the males in this bucket. When I first saw this process, I was like, “This is a violation, this is crazy”. But they were so transparent about it. It’s amazing that fate happens in that bucket and that a human facilitated that process. I am just so fascinated by it and confused and feel so weird about it. I think it’s important to look in different spaces, not just the sciences, but also agriculture and also my own relationships with pets to begin to have a better basis for asking these questions. But I almost think in animal husbandry and in agriculture, they have a much better understanding of our relationship to animals.

OKB:

Where did your interest in water begin?

SF:

With clear materials. I remember I was working at this Texan jewelry brand and they would just have bins of these fake gems, and I was just so attracted to them. The jewelers told me about resin. That day I went and got resin and had no idea how toxic it was, but I just instantly fell in love. It’s this thing you can’t eat, but you want to eat. I think about my attraction towards it as wanting to quench my thirst with an object, and I’ll never quite be able to quench it, but it’s constantly pulling at me. It suspends me in the space of being in between, of not actually getting the gratification, but also knowing it’s almost there.

OKB:

I’m curious if you ever taste your material, if that’s a part of your process? Is that something that you’re interested in?

SF:

Usually my friends will eat my materials more than me, but yes. I don’t trust [materials I’ve made in] my studio, but when I’m making it in the kitchen, I have tasted stuff. There is a lot of scent involved. I also like not knowing, it almost feels like if I know what it tastes like, then I’ll know the thing.

A lot of these methods are really interesting because they relate to food and the product is something almost edible that you could technically still consume. But it’s interesting to also leave it undigested there in front of you, and to see how long it stays there, because this [fish skin tanning] method does really fix the material chemically. It will replace the water molecules with fat, and that helps to cross link the collagen fibers. I kept that process in mind, and I was looking at energy extraction and energy harvesting, and because of working so much with water and wanting to control it.

OKB:

Do you eat fish?

SF:

Oh, yeah. I love fish. I don’t eat meat. I don’t like the taste of it, but I’m also fascinated by people’s love for meat.

OKB:

This show feels very playful, whimsical. You play with scale in a way that feels almost child-like, especially in Some days I’m edible. I’m curious about what your art-making practice was like as a kid?

SF:

I remember I just loved hot glue guns so much. There was this instantaneous nature to it where you can just bind something so quickly. I would make cardboard forts for my cats, but I was really mostly just drawing and organizing. I loved collecting and arranging objects. I do love small things and when things are scaled down.

OKB:

Speaking of organization, on your site and here in your studio you have this amazing material library. Can you talk about the importance of taxonomy and your cataloging process?

SF:

I think [it was] from seeing scientists work and spending a lot of time with them, I got into this labeling technique. It’s still really hard to get myself to do, but I think it is really important to look back on [these iterations] because a lot of things do also disintegrate over time. And a lot of the things that I may think in the moment are a failure I later come back to, and I’m like, actually, I love what it’s doing for this reason. So it’s been a really great archive for myself, and also to help to recall certain recipes or days where a specific thing happened. And then, I also have binders of my notes and writing that don’t have visual samples, but correspond to certain recipes.

I love knowing how things can be transformed. I think that the things that come from time and corrosion and entropy are just so fascinating and beautiful. I do also think that if you just don’t touch the piece, it will be okay.

OKB:

Do you have any routines that are a part of your practice?

SF:

Right now, I’m caring for the algae, I have to come [into the studio] and check on them. And the mycelium. Zooming out, I think one routine might be just going through a rabbit hole of materials, and also looking at the things I’m thinking about and tying those materials to the to the concepts I’m researching. And then I just do a bunch of experiments. I’ll also reach out to people and go on site visits, because I always want to know more about the materials. The experimental research phase is a really big part of processing the work. Then I go into production mode once I have things figured out, but it’s not exactly linear.

Entropy always finds a way, and it usually finds it through water.

OKB:

Do you have other collaborators or people you consider collaborators in your practice that played a part in this show, and maybe more specifically, people who inspired you?

SF:

I think this is one of my favorite parts of making: doing the experiments and then getting to later share them. [I think that] seeing what people do with it is just incredible. It makes me so happy.

I’ve been working with Acme, a Fish Smokery and I got to tour their facilities. That’s awesome. I’ve been reaching out to a lot of fishermen lately. I really want to be taken fishing soon. Some artists I’ve been looking up to are Laure Provost, Maëlis Bekkouche, Jes Fan has been doing some pretty crazy things with fermenting soy milk, Lee Pivnik, Catherine Telford Keogh, and Agnes Questionmark.

OKB:

It seems a significant part of your practice is collecting and finding local resources to work and collaborate with. How does your work change as you move around?

SF:

When I do go somewhere it is about building relationships with that community and spending time with them and learning and listening to them. I have to find some way to involve them in the work,the show or whatever I am doing, if that’s possible. Community feels really important to making all of this happen, I can’t do it by myself. And yes, it definitely depends on the resources. I try to do some research beforehand, on the infrastructure or the history of relationships to fish or water, depending on the space. Those are starting points. But I’m open to things taking me in a different direction. I like to find places to work with local materials or a waste stream, and just to understand how those materials relate to the environment and the land there.

OKB:

Was there a piece that was particularly challenging in Resurrectura?

SF:

Literally each piece was challenging in a different way. With the mycelium, everything was getting contaminated. Mold would grow, and I wanted to be like, “Oh, cool”, but also I would read about it and realize, you should not be inhaling [the contaminated mold]. It really pushed my understanding of what it means to try to grow a material and the care and also just the failure involved in it. There’s nothing about these materials that is fixed or finite. Entropy always finds a way, and it usually finds it through water.

Sasha’s Reading List: