Traces of flour left by overlapping footprints marked the street outside Madeline, a former Western-style dessert shop and cafe in Taipei. These imprints did not come from the bakery kitchen, but instead, came from the enveloping exhibition ‘Producing Space: Divergence, Convergence, Dessert Shop’ by artists Sara Wu and Sean Tseng under their studio collective ss space space.

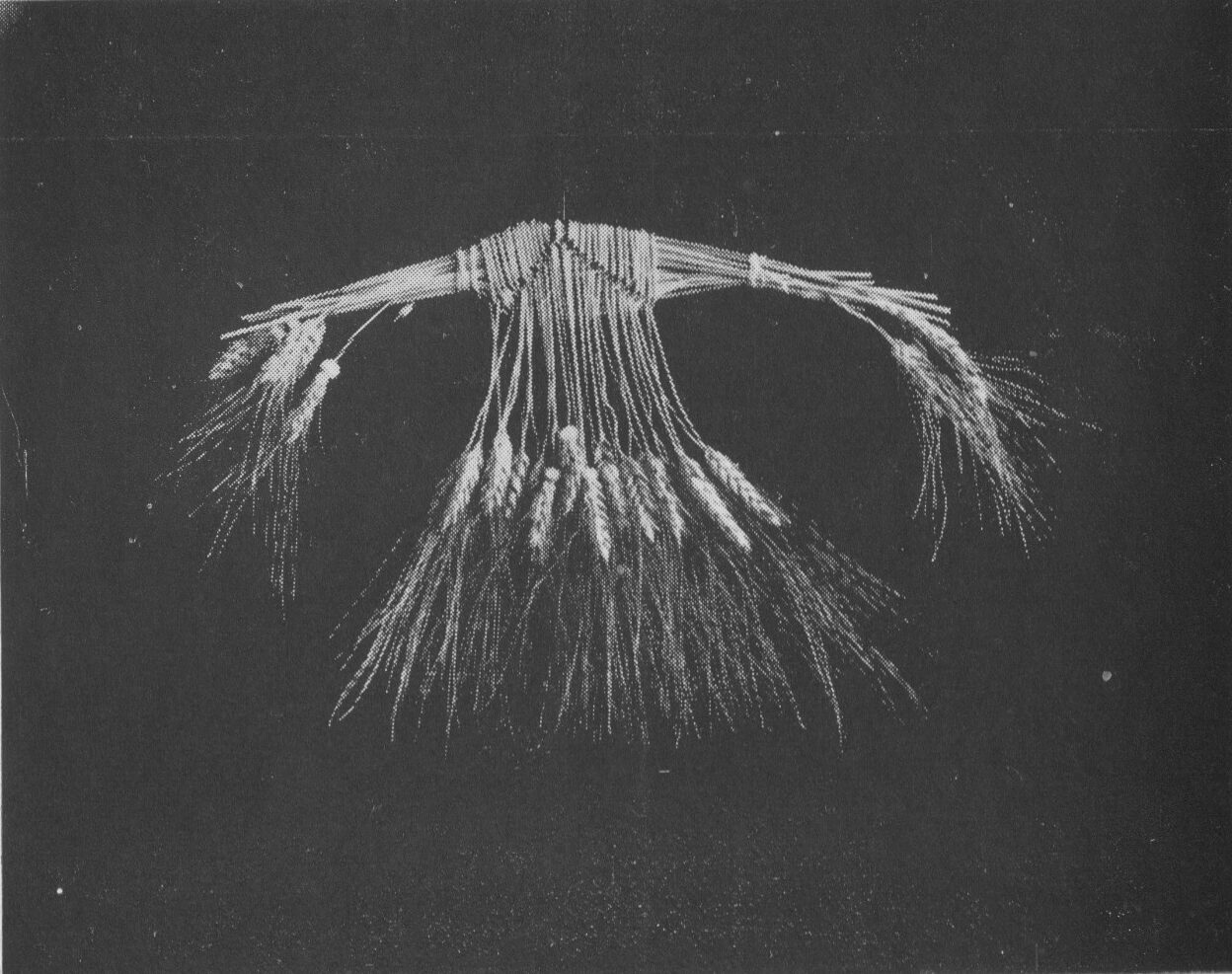

Occupying the entirety of Madeline, the site-specific installation, which was on view earlier this October, highlights and experiments with the materiality of flour. A dusting of raw flour covered the floors, batter was used to paint the window, shop glass, and door, and a sizable dough-like sculpture made from wheat husk and plaster dominated the space. Wu and Tseng’s exploration also incorporated and referenced baking tools. Rolling pins were placed underneath the dough-like centerpiece for support, storage containers stacked on top of each other mimicked the balance of a sugar cube tower, and a carefully assembled object resembling a cake stand hung low from the ceiling, where its metal tiers reflected the shifting movement of surrounding flour with each visitors’ steps.

Wu and Tseng both come from backgrounds in sculpture, and currently work across photography and installation. Their joint practice is grounded in building spatial experiences, where they share a particular sensitivity to material engagement—one that often obscures the familiar and activates senses beyond the visual.

In ‘Producing Space’, the artist duo focused on the visibility of flour to create an environment that could be felt. “In its raw form, flour is usually only visible in the production stage,’ says Wu. “Beyond that, we only seem to engage with it through taste.” Tseng adds, “we wanted to make a work that not only spoke to the past operations of this space as a dessert shop, but also foregrounded the raw material of flour by constructing an installation for the body to experience.”

It is indeed unusual to walk on flour, to feel and shape it with the soles of our shoes. This setup made flour inseparable from the space, in a way that seemed to almost break down and collapse the former bakery to its defining material. For their exhibition, Wu and Tseng noted the centuries-old history of flour, as well as its complex foodways in Taiwan, where cereal is an introduced crop and wheat is an imported grain.

‘Producing Space’ worked with cake flour from Camel Brand (the cartoon camel logo inspired Wu and Tseng to think about global trade), a product by Lien Hwa Milling Corp. The largest flour mill business in Taiwan, Lien Hwa t was established in 1952, during the period of US aid (美援 meiyuan) where the US provided economic, humanitarian, and military support to post-war Taiwan from 1951 to 1965 for the regional security of Asia-Pacific. During this decade, US assistance also included fostering private enterprises, restoring public utilities, and importing consumer goods. As one of the largest beneficiary countries, Taiwan consumed surplus agricultural products from the US through the “Food-for-Peace Program”1. Flour was a key import, and bags of it were delivered to churches to be handed out after sermons, and to the mainland exodus in the military dependents’ villages (眷村 juancun). This greatly supported the new immigrants, many of whom were northern Chinese refugees of the Chinese Civil War, because they primarily consumed wheat-based foods as opposed to the Taiwanese rice-based diet.

- 1. Man-houng Lin, I-min Chang, and Wei-chen Lee, “The US Aid and Taiwan”, 2012

Production of wheat soared in Taiwan during this time with the US backing an existing, but small, flour milling industry that was first established during the Japanese colonial era (1895-1945)2. By 1952, instead of flour, the US distributed wheat grain to Taiwan and assisted with the setup of large factories like Lien Hwa to upscale milling processes. This development enabled Western-style baked goods to become more accessible and prevalent. Public cooking classes for wheat-based foods and Western-style pastry courses held for local communities further transformed this auxiliary food source into a staple3.

Taiwan was one of the few countries that successfully sustained growth independently after receiving US aid.4 However, flour mill businesses operating today still rely heavily on imports of wheat and cereal crops, as climate conditions in Taiwan are not optimal for cultivation.5 80% of the crops milled at Lien Hwa are from the US (the rest are from Canada and Australia). While the 2021 agriculture census showed the steady rise of wheat consumption in Taiwan post-US aid—and subsequent fall of rice consumption to a historic low of 31.3%—this trend can be traced back to three other colonial periods.

- 2. Yu-jen Chen, “Han Pastry, Taiwanese Snacks, and Bread: Formation of Bakery Industry and Transformation of Consumption Culture in Japanese Colonial Taiwan”, 2021; Council of Agriculture, “Food Production and Activities in Taiwan Area”, 2010, p. 9-10

- 3. Man-houng Lin, I-min Chang, and Wei-chen Lee

- 4. Yu-jen Chen, p. 1

- 5. Council of Agriculture, “2015 Agricultural Trade Statistics of the Republic of China”, 2016, p. 61-63, 98-99; “Regulation of Wheat and Wheat Flour Imports”, 1994, p. 79, 97

The history of bakeries in Taiwan is one of industrialization, democratization, and post-colonialism.

Wheat planting in Taiwan first began in the 17th century under Dutch colonization (1624-1662, 1664-1668) and expanded under Qing dynasty rule (1683-1895).6 It continued during the Japanese colonial era (1895-1945) of mass industrialization, where Taiwan’s bakery industry first emerged and burgeoned. The Japanese established the first systemized, industrial milling factories with European machines and additional grains from Fujian province, Japan, and even the US in the 1930s. Although most of the flour produced in Taiwan was exported back to Japan, the increase in local bread production saw the first dedicated bakeries open outside of the general stores that had begun making and selling baked goods.7 The growing acceptance of bread was reflected in language, as pan entered the Taiwanese Hokkien vocabulary, coming directly from the Japanese パン (pan) pronunciation for bread.

- 6. Yu-jen Chen, p. 50

- 7. Ibid., p. 73

While Han-style Taiwanese pastries and rice cakes existed prior to Japanese colonization, they were mainly reserved for ceremonies (weddings, 60th birthdays, a baby’s first month), festivals (Mid-Autumn, New Year), and religious occasions (Qingming Festival). These pastries bore ritual and social significance but were often expensive and complicated to make, limiting them to the upper class.8 This differed from the non-ritualistic, simple, and convenient Japanese snacks and breads introduced in Taiwan, qualities that researcher Yu-jen Chen describes as “endowed with symbolic meanings of modernity”.9 Naturally, by the first half of the 20th century, the consumption of bread and wheat-based foods grew, incorporated into the urban population’s regular diet.

The history of bakeries in Taiwan is one of industrialization, democratization, and post-colonialism. The industry continues to flourish today, where as of 2018, there were more than 5000 Western-style bakeries in Taiwan, not including the thousands of convenience stores that sell bread and pastries, and cafes with wheat-based desserts. The importance of bakery culture is highlighted in its prevalence, and it is within this context that ‘Producing Space’ was created.

- 8. Ibid., p.55

- 9. Ibid. Abstract.

The exhibition’s closing performance further considers the work within Taiwan’s foodways of flour. In ‘Particulates in __’, dancers Zofie Wu and Ebel Hsieh of ShenYan Dance Theater transformed Madeline into a domestic space. They moved through the floured floor and engaged in a morning routine of getting dressed, making coffee, and eating bread. The 15-minute choreography centered around the everyday, and the performers’ monotonous movement and engagement with the materials in the exhibition highlighted a quotidian, a commonplace, for which flour exists in Taiwan today.

‘Producing Space: Divergence, Convergence, Dessert Shop’ facilitated these explorations through a meditation on flour that sought to render it visible. “Working with flour as a sculptural material made us notice its presence everywhere,” the artists reflected. In their installation, it certainly was found on all surfaces and beyond. During the de-install, Sara Wu remarked how the flour “even allowed for dust to be seen.”

- 1. Man-houng Lin, I-min Chang, and Wei-chen Lee, “The US Aid and Taiwan”, 2012

- 2. Yu-jen Chen, “Han Pastry, Taiwanese Snacks, and Bread: Formation of Bakery Industry and Transformation of Consumption Culture in Japanese Colonial Taiwan”, 2021; Council of Agriculture, “Food Production and Activities in Taiwan Area”, 2010, p. 9-10

- 3. Man-houng Lin, I-min Chang, and Wei-chen Lee

- 4. Yu-jen Chen, p. 1

- 5. Council of Agriculture, “2015 Agricultural Trade Statistics of the Republic of China”, 2016, p. 61-63, 98-99; “Regulation of Wheat and Wheat Flour Imports”, 1994, p. 79, 97

- 6. Yu-jen Chen, p. 50

- 7. Ibid., p. 73

- 8. Ibid., p.55

- 9. Ibid. Abstract.