How does a food crisis occur? What factors create conditions of scarcity? What can be done about it? These questions sit at the heart of The Hunger Tales, a resource-management board game hatched by Bakudapan Food Study Group, an eight-woman collective founded in 2015 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Bakudapan examines the issues around food and its broader contexts—political, social, cultural, environmental—across multiple methods and modalities, such as national and international art exhibition, public programming and performance, independent publication and communal gastronomic practice. The Hunger Tales experiments with new avenues of communication, bringing Bakudapan’s existing research on the food ecosystem to a wider audience.

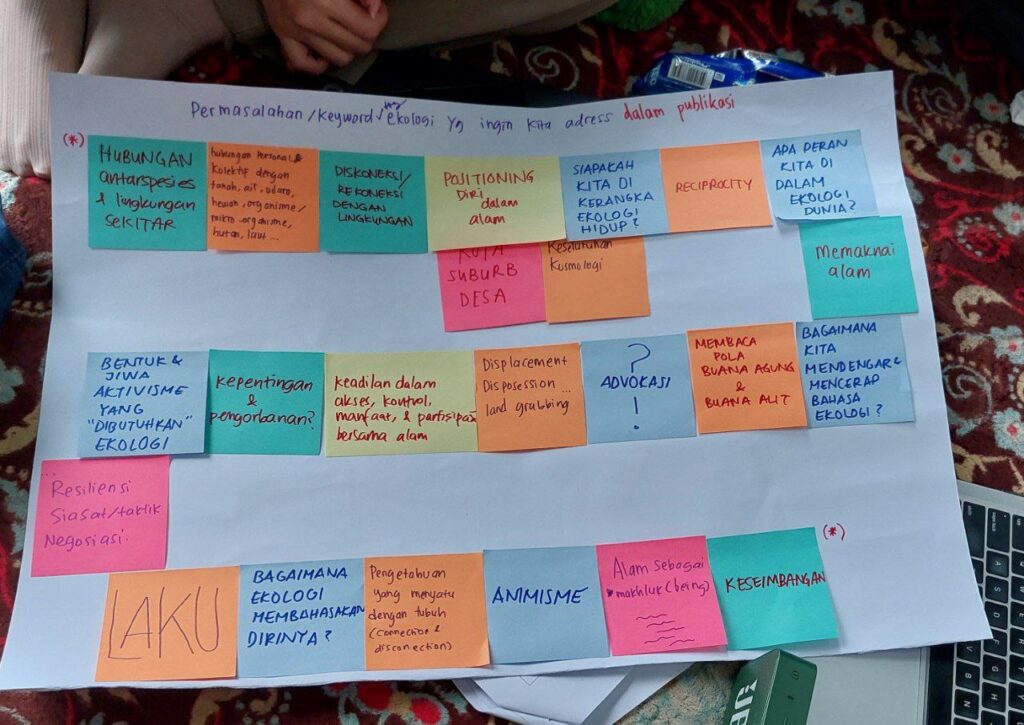

Esty Wika Silva, a member of Bakudapan, explains that the research leading to The Hunger Tales went from general to specific. “[Bakudapan] didn’t organize a particular research for the creation of the game, but gathered previous research notes and mapped them according to the need of The Hunger Tales [prototype], that is politics and food crisis in general in Indonesia. As time went by, Bakudapan had the opportunities to deepen the research and zero in on specific regions [with their specific issues].” For example, in Palu, the capital city of Central Sulawesi province where Silva and team conducted subsequent field research, the food-related issues are complicated by the fact that soil usage is overtaken by the extractive practice of the sand- and nickel-mining industry, which leaves next to nothing for local food production. This makes Palu dependent on surrounding regions for sustenance. On the other hand, according to Shilfina Putri of Bakudapan, the collective was interested in the board game format as a tool for creating a playful yet educational space for increasingly urgent discussions around food politics, “The board game is political in theme yet very much personal as it touches our everyday reality and personalized by each player’s playing style, which [depends on] the given role and the character of the players, giving all kinds of possibilities to the game, beyond winning and losing.”

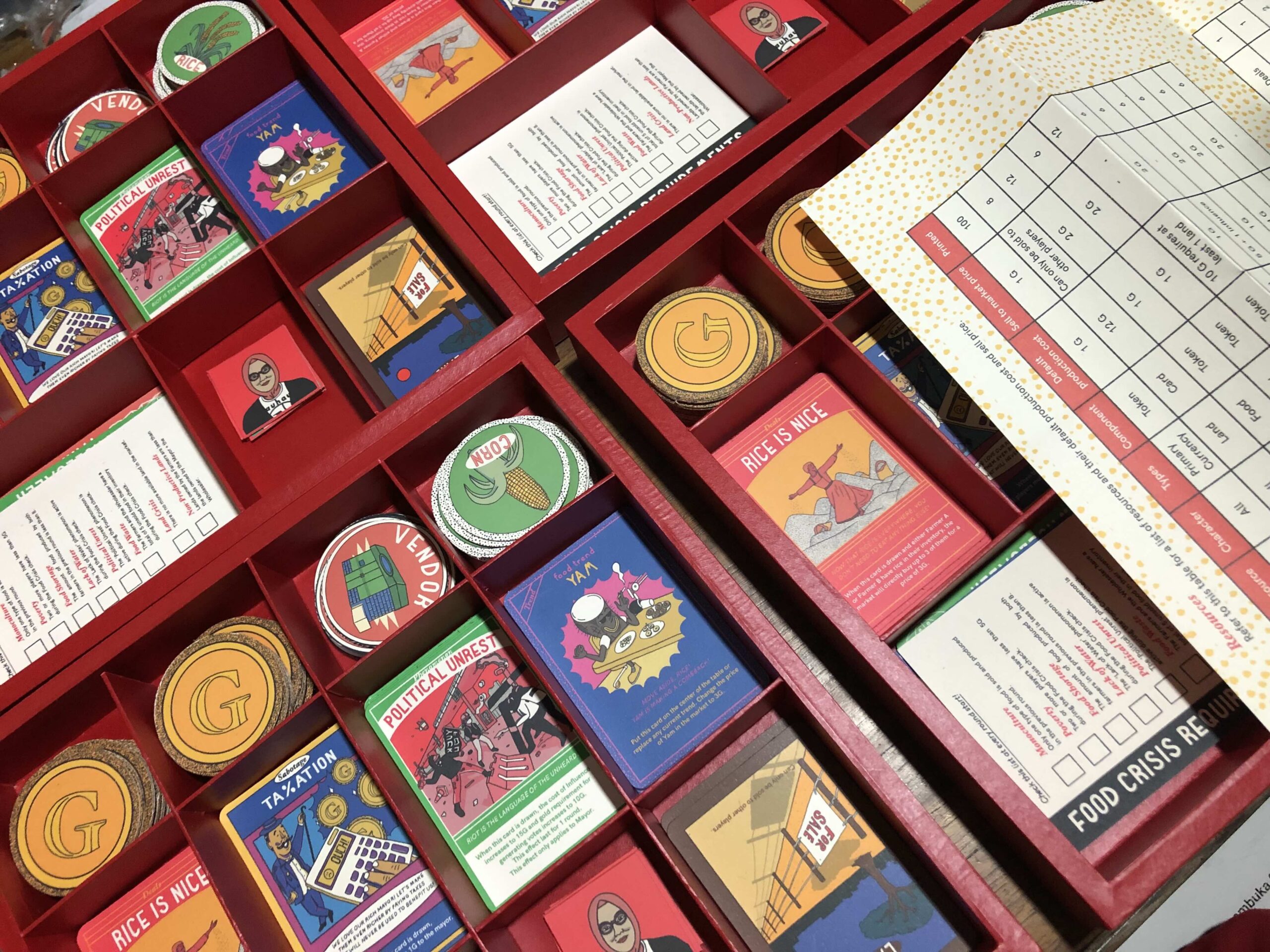

The Hunger Tales revolves around a few stakeholders that players can play as: Mayor, a proxy for the policymaker, Wholesaler, the food distribution middleman, and two farmers with different back stories that should influence their decision-making process. Farmer A is motivated by family economics and in most iterations, Farmer B is interested in biodiversity. For each turn, a player draws an Event card, which dictates the conditions for playing. These dealt cards affect the luck and chances of each player. “Trend” cards introduce economic changes, things like shifts in market price for crops or the boom and bust of certain commodities. “Phenomenon” cards can alter the course of the round, standing in for social and environmental factors, instances like a dry season, that are often beyond players’ control. Then, there are “Deals” cards which represent opportunities for profit and growth for the farmer, and, of course, a “Sabotage” card, which serves the opposite, disrupting the player’s progress.

To win The Hunger Tales, players aim to accumulate a certain amount “Gold”, the currency used within the game. There is a caveat however, and winnings are also limited by effects on the wider ecosystem that fosters food crises. For example, when a Farmer buys too many of the same commodity (known as a “Token”, these commodities represent rice, corn, yam, wheat) per round, a monoculture can emerge as one of the symptoms of an impending food crisis. Meanwhile, much like in real-life scenarios, the Mayor and Wholesaler usually tend to gain more Gold than Farmers, with the rounds giving them an upper hand by way of capital-holding such as the Mayor’s salary, although the Farmer’s amount of Gold to meet as a winning condition is set lower than the rest. “The economy of the game is rather complex but pretty intuitive—enough to illustrate the problems within our food systems.” Meivy Andriani Larasati, another Bakudapan member, highlights, “The pressure is gradually higher, for example when Wholesaler keeps gaining more gold while a Farmer can only plant a few commodities. The players can empathize and reflect on how the existing food system turns out to be unfair.” Like real life, the game can end prematurely if the symptoms leading to a food crisis persist for several rounds in a row.

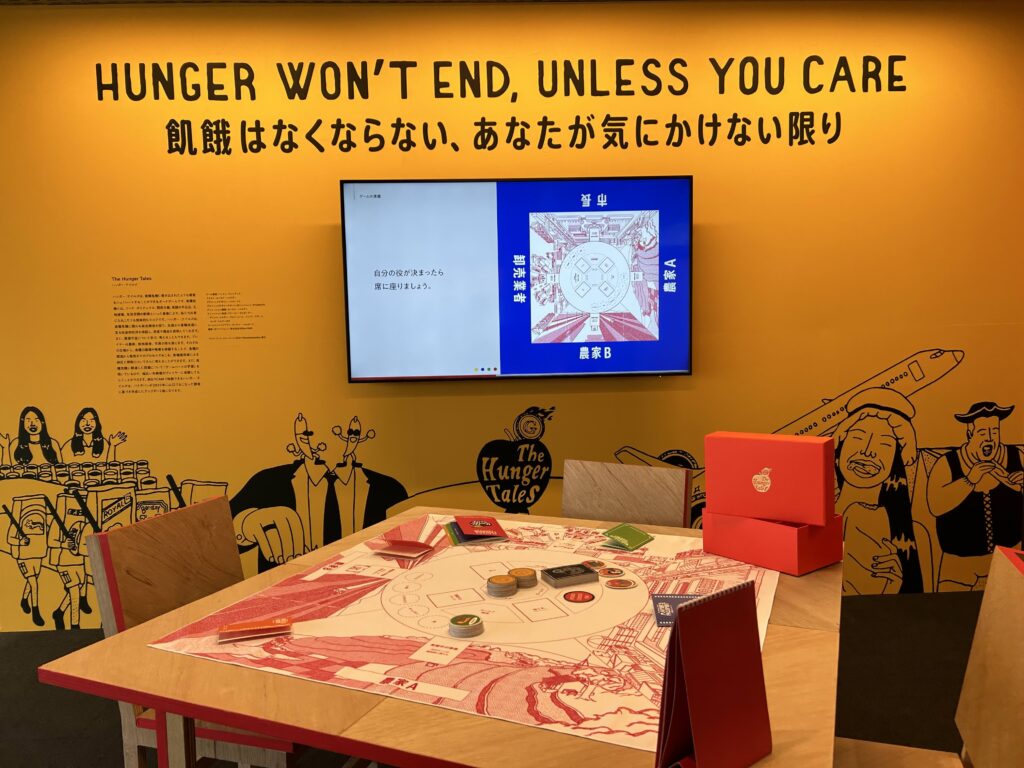

First conceived at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, The Hunger Tales began as a part of the group exhibition Phantasmapolis at the 2021 Asian Art Biennial in Taichung, Taiwan. This bilingual (English and Chinese) prototype was developed in collaboration with visual designer Kanosena and game designer Pandhu Vandhita. On devising the fresh and distinct visual identity of The Hunger Tales, with red-dominant color palettes and cartoonish illustrations, Kanosena gathered various references from the vast landscape of Indonesian design vernacular: food packaging, food stall and restaurant signage, propaganda posters, news of absurd and wasteful “food influencers” with gluttony for expensive meals, humorous tributes (such as Korn vocalist Jonathan Davis as the “Corn” token) and subtle political satires. Whether in drawings or animations, he succeeds at imbuing Bakudapan’s food crisis research with vividity, in a way, tempering the bleak theme.

This is indeed what I first noticed with The Hunger Tales: everyone, from the creators to the players, seems to be having actual fun while learning simultaneously. For Vandhita, it was important to strike the right balance between the educational objectives of The Hunger Tales with the ideal experience of playing the board game, “Because the fun gets everyone talking [about food crisis issues]!” In his design, he paid special attention to the dynamics between stakeholders and players’ investment in them. He emphasized that The Hunger Tales can’t be too ‘boring’ or information-packed lest the players are not spirited to learn, it can’t be too generic either lest the specified discussions of food crisis come to a halt.

Since the release of the first Hunger Tales, Bakudapan has released several other iterations, all developed by Kanosena and Vandhita, with each new version an opportunity to fine-tune the board game. Bakudapan has shown The Hunger Tales at Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (2023, Japanese version), FOODCULTURE DAYS at Switzerland (2023, French version), Pekan Kebudayaan Nasional (PKN) Indonesia 2023 in Jakarta—where Bakudapan released localized versions of the board game that they had developed at prior residencies hosted by Forum SudutPandang in Palu and Simpasio Institute in Larantuka. This long-standing, ongoing process of research, collaboration and tweaking culminates in a model that seeks to mirror ecological realities and shines a light on topics that might be obscure to the general public.

Take the Larantuka version, for instance. The small region located in the district of East Flores, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia, has a population of forty-five thousand people. The food-related issues present in Larantuka are dependent on government programs and NGOs that champion plantation or cultural festival models as solutions without actually getting into the roots of the food issues. The region has also experienced a shift in the urban landscape, with a growing number of residents leaving the farming sector. This has made Larantuka more dependent on trading activities for produce. Larantuka is more involved in the global economic process by way of [foreign] investment in the farming sector and fisheries. Price fluctuation often happens at the height of Adat events in Larantuka, such as Semana Santa (Holy Week) and centuries-long whale-hunting tradition. As such, factors such as climate change and unpredictable pests pose a tangible threat to local economies due to the inflation. For the development of the Larantuka edition of The Hunger Tales, Bakudapan’s research spanned quite widely from local food and customs to climate change as well. In order to perform this research, they invited the host community at Simpasio Institute to play an early version of The Hunger Tales, and respond with feedback—even asking players to propose new playing cards that might be suitable to the local context. The results are new Tokens such as “Fish” and “Pig”, and an Event card allowing players to buy fish tokens at a lower price and/or cut out an extortive middleman. The same collaborative method was also applied at Vevey and other locations, including at PKN when a “Farmers Unionize!” card was issued to reward Farmers for unionizing, therefore increasing the winning chance against the Mayor and Wholesaler players.

The most recent iteration of The Hunger Tales was developed in August 2024 in response to Bakudapan’s residency at the Singapore Art Museum. Monika Swastyastu of Bakudapan explains that this latest version might be the most different from previous ones due to Singapore’s unique food systems. Where soil-based farming is common in Indonesia due to ecological factors and non-govermental land ownership, stakeholders in Singapore (businessmen, laymen, farmers) have to loan the land from the government should they want to cultivate plantations. This governmental support is only available for high-cost, high-tech farming initiatives. Because vertical systems don’t really allow for carbohydrate-heavy commodities to thrive, the primary output of government programs are vegetables and eggs. This alternative context prompted a new exercise in game design for Bakudapan, who were tasked with extrapolating the values of a different food system into their existing game format. However, as Monika states, “The essence [of the game] will not change, from making known the real-life issues and the impending food crisis.” This exciting game development is one to look for, surely, among other goals that Bakudapan has in mind. In the future, they hope to produce The Hunger Tales in a more cost-efficient way, bringing it to more public events beyond art exhibitions. Last July I first had the pleasure of playing the game at the Bakudapan Game Day at KUNCI Study Forum and Collective, where I took on the role of Farmer A who went for broke. It says something, I think, to the novelty and impact of the board game when the participants—from curious non-gamers to food-issue enthusiasts to seasoned players—then kept asking to purchase The Hunger Tales to play at home.