Queering Theory untangles critical theory through the multifarious lens of queer theory, food, and ecology.

Imagine you’re standing on the crest of a hill. Rolling fields of golden wheat stretch before you, shimmering under the sun’s heat. This bucolic landscape paints a familiar image, one 10,000 years in the making. For much of human history, fields like these have held the promise of survival; another year’s food held within a single vista. Yet as of late, the view has become slightly more nefarious than it has first appeared. A closer look provides a different perspective, one of unsettling, imminent doom.

Over millennia, myriad farmers have played their part in an ongoing interspecies collaboration between us and our crops. For much of this history, this collaboration has occurred on a highly site-specific level, as every farmer’s crop slowly adapted to their locale over successive generations. These are called ‘landraces.’ Though they might be variants of the same species, landraces are genetically diverse enough from field to field to ensure against succumbing to the same pestilential or environmental threats.

Throughout agricultural history, the yield-driven farmer’s zenith of cultivation would have been monoculture: the perennial cultivation of a single species in a given area. Yet until the turn of the 20th century, this was unattainable. Nature cannot sustain monoculture. Growing the same crop year after year depletes the soil of its fertility without affording it time to replenish. Doing so would extend an open invitation to pests, which would have posed a very real threat of famine.

Historically, to avoid this, farmers relied on diverse, rotating planting. In medieval Europe, arguably the first intensively farmed landscape, the open-field system divided land into strips during growing seasons, which were then left to graze for the rest of the year.1 These fields’ uses would rotate, with one fallow year in every four to allow the soil to regenerate. These practices, which today resonate as ecological in their land management, would then have been about survival.

- 1. Thomas, K. (1983). Man and the Natural World. London: Penguin Books.

It is telling that the blueprint upon which modern monoculture is built is the plantation system. Whereas monoculture relies on synthetic fertility and mechanisation; plantations achieved high yields through chattel slavery and the displacement of vast populations. Both systems have wrought widespread devastation and changed the course of global history.

It is indicative of just how inconceivable monocultures would have been that the term was only coined in the 1910s. The rise of the term correlates with a broader drive within agriculture to grow the unnaturally high yields upon which we now rely. What brought on this shift was the Green Revolution: an opportune solution to the very real threat of increasing populations outstripping agricultural outputs. The Revolution’s success relied on three main innovations: a cocktail of chemical intervention, artificial fertilisation and intensive breeding.

The first two of monoculture’s innovations found their genesis in the laboratories of Fritz Haber, a German agricultural chemist. Unfortunately, Haber’s inventions also served as highly effective munitions. The atmospheric chemicals his Haber-Bosch process captured were highly explosive, and his pesticides could melt flesh from bone. Both found a fitting arena in which to test their destructive mettle on the battlefields of WWI.

- 2. Mintz, S. (1986). Sweetness And Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin: London. 47-53

- 3. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- 4. Ritchie, H. (2017). How many people does synthetic fertilizer feed?. OurWorldInData.org.

- 5. Barney Pau, 1.

His pesticides wrought such devastation that they were later banned by the Geneva Protocol.6 Unfortunately, the Allies Forces who authored it seemed somewhat confused about their definition of chemical warfare, as they continued using similar pesticides on the battlefield despite the Protocol.7 Case in point: the infamous ‘defoliant’ Agent Orange.

The Revolution’s third achievement is perhaps its greatest: intensive plant breeding. Seed-saving has been used for millennia—select your best seeds; plant them the next year; tailor your crop. Historically, this engendered the landraces previously mentioned. The Revolution intensified the principles of this, adapting a handful of high-yield species to be universally growable—with artificial support—and replace less productive landraces.

This is largely thanks to agronomist Norman Borlaug, ‘the father of the Green Revolution.’8 Borlaug’s innovations in plant breeding are said to have saved a billion lives.9 Borlaug’s new wheats resisted abiotic (environmental), and biotic (pestilential) stresses, increasing yields by two-thirds. Despite this success, the scientist was among the first to recognise the ephemerality of his own work, noting in his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech that this form of agriculture was only a temporary solution.10 Since then, his innovations have arguably helped facilitate a further few billion births. His ‘temporary solution’ is now indispensable, with half the world’s population now depending on this legacy.11

- 6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geneva_Protocol#Chemical_weapons_prohibitions

- 7. https://www.history.com/news/agent-orange-wasnt-the-only-deadly-chemical-used-in-vietnam

- 8. Scott Kilman and Roger Thurow. “Father of ‘Green Revolution’ Dies”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- 9. Avery, Dennis T. (2011). “Winning the Food Race”. The Brown Journal of World Affairs. 18 (1): 107–118. ISSN 1080-0786.

- 10. Borlaug, Norman E., (1970) ‘The Green Revolution, Peace, and Humanity’ Nobel Foundation. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1970/borlaug/lecture/ Accessed 13/06/24, 5

- 11. Ritchie, H. (2017). How many people does synthetic fertilizer feed?. OurWorldInData.org.

You might be wondering why we’ve delved so deep into monoculture’s muddied past, when this series covers queer theory? Monocultures affect more than our fields; our minds, too, are tailored to uniformity. This is a concept explored by the philosopher Vandana Shiva, who ties the monocultural mentality to the Global North’s notions of capitalism and wholesale extraction. She emphasises its forceful implementation in the Global South and the subsequent erasure of the traditional, indigenous and ecological approaches to growing. For where monocultures may be unmatched in efficiency and production they’re similarly unrivalled in destructive potential.

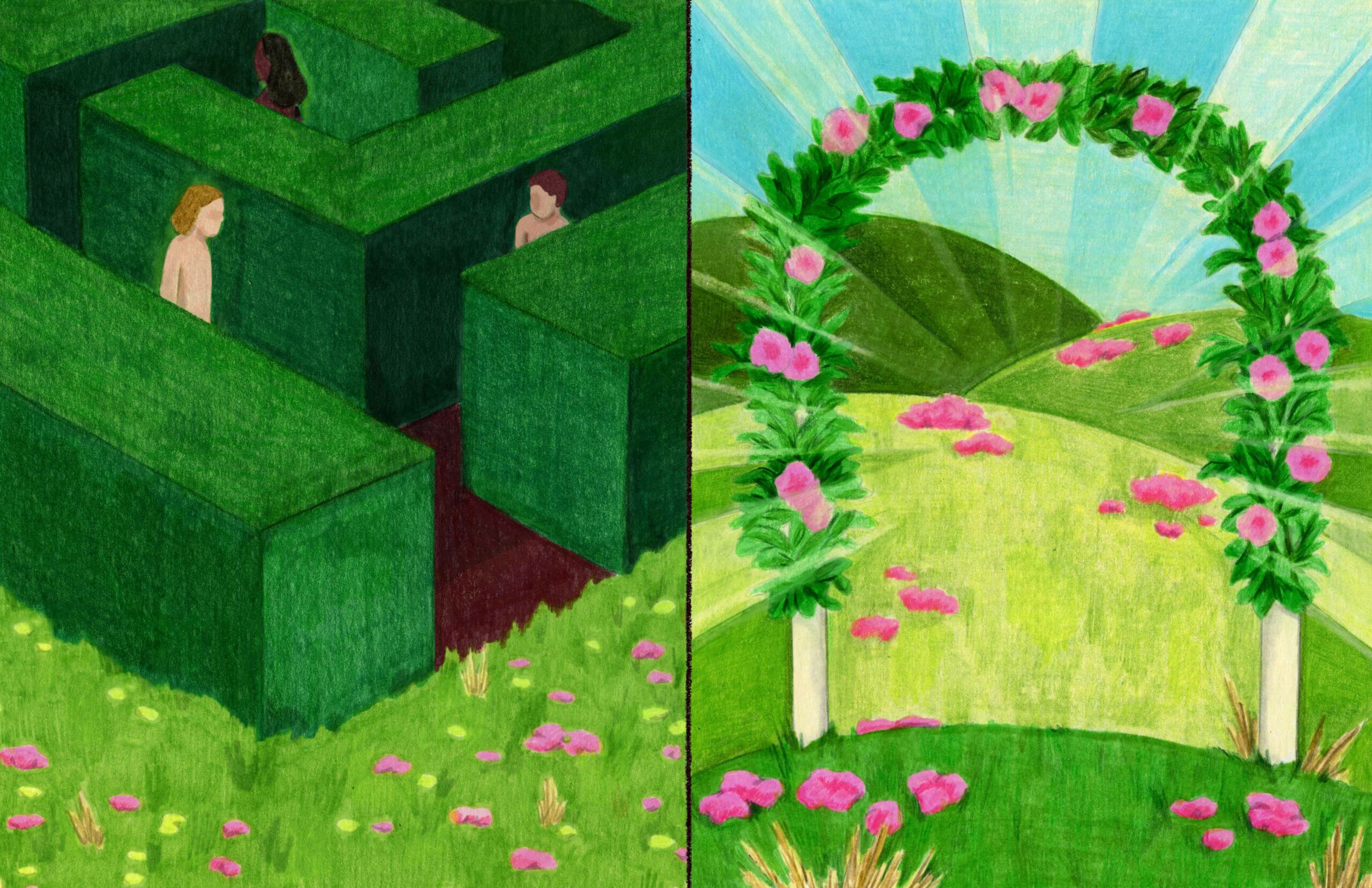

When transposed notionally, monocultivation is the maintenance of normative thinking; a mentality which is similarly harmful to the practice. This thinking promotes a singular ideal which, in contemporary culture, predominantly revolves around white-heteropatriarchy.12 In this way of thinking, diversity—‘impurity’—is eschewed to prevent contamination. ‘Impurity’ and ‘contamination’ are heavy words with which to refer to a person, and both have a history of weaponisation.13 Yet, loaded as they are, it is this thinking that monocultured mentality maintains.

So what might queer theory have to do with this? Comprehending how ingrained our reliance on agricultural monocultures is is integral to identifying the ways in which our mental monocultures are formed. Seeing monocultures thus—as a norm—helps us identify how they might be queered. In an agricultural context, this helps us look beyond the binaries norm of the monoculture, to one of nature’s most reliable insurance policies: promiscuity.

- 12. This term is borrowed from sociologist Andil Gosine’s essay Nonwhite Reproduction and Same-Sex Eroticism in Catriona Mortimer-Sandiland et al’s Queer Ecologies (2010).

- 13. Natarajan, M., Wilkins-Yel, K. G., Sista, A., Anantharaman, A., & Seils, N. (2022). Decolonizing Purity Culture: Gendered Racism and White Idealization in Evangelical Christianity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 46(3), 316-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/03616843221091116

This term is perhaps most familiar to us in relation to transient sexual relationships, something which, under Abrahamic traditions, has been widely culturally suppressed for millennia. As such, we see it as dirty, impure, and unserious. It is in this that its ecological strength lies, for impurity equates to diversity, which biologically speaking is security. In layman’s terms: the more diverse a species, the better chance it has to resist biotic and abiotic stresses. In his Entangled Life (2020), mycologist Merlin Sheldrake suggests that interspecies promiscuity has historically aided in a species adaptation to climatic change. In a post-Ice Age landscape, plants with a more versatile roster of fungal partners with which to symbiotically engage could better colonise land newly uncovered by retreating ice shields.14

When promiscuity is applied in a social context, it begins to open up monocultured thinking, queering it both notionally and literally. Here, Between the Cracks comes to the fore, for weeds’ wonderful ability to resist and intermix is the inspiration our dry monocultures need. Indeed, this has led to some of our favourite crops. Many once-weeds are now enrolled in our roster of domesticates to take advantage of our hospitality and proliferate. Rye and oat, once reviled as interlopers in the wheat field, are now favoured grains. Species of wild mustard, too, curried our favour with their flavour, becoming progenitors of many modern brassicas. These widely consumed species testify to our capricious mental willingness to turncoat as soon as use is found. Far be it from me to suggest weeds in field peripheries whisper dissenting ideas into the ears of the grains within, but this isn’t far from the truth. By existing within the peripheries, weeds offer their genetic diversity to cross-pollinate with cultivated species, thus diversifying their crop.

My link between promiscuity and queerness is in their overt expression against oppression: promiscuity in diversifying singularity; and queerness in its inherent otherness. Both persist outside existing systems of thinking in their adherence to the norm. This is what the queer theorist Jonathan Dollimore calls ‘straying’—cited in this series’ second article—which reveal the norms’ coercive nature.15 Importantly, it is not my intention to label queerness as inherently promiscuous. That assumption is weaponised against queer people to label us immoral and unrestrained; a prominently example of which is the AIDs epidemic.16

- 14. Sheldrake, M. (2020). Entangled Life. London: Penguin. 156

- 15. Dollimore, J. (1991). Sexual Dissidence. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 106

- 16. Este, J. (27 November, 2018). AIDS: homophobic and moralistic images of 1980s still haunt our view of HIV – that must change. The Conversation.

Similarly importantly, nothing said here is absolute. In fact, it’s the inverse; for by presenting a single ideal, absolutism is tantamount to monocultivation. Instead, this is a proliferation of ideas, intended to diversify thinking and engender new thought. This essay is convoluted: a messy set of contradictions. But that is also its point. Monocultivation has led us to believe it is a panacea, both to global food security and social order; yet its ecological and cultural devastation indicates it as anything but. One line of thought is not globally applicable; just as one system of agriculture is not naturally possible.

It is thus in convolution that I embed my message. There is no ‘one way;’ no single solution. Instead, we must rely on infinitely diversified thinking to get out of this monocultured mess. Far from the unilateral approach which society predominantly takes, we need to be independent and unique; innovative and unusual. Here, queer promiscuous thinking might help us see solutions otherwise hidden, for as a methodology, it diversifies existing systems and promotes alternate thought.

We cannot grasp the complexity of how to undo monocultutivation; it will take an unimaginable change to alter our reliance upon it. So rather than trying to tackle the problem, this is a treatise on how to approach it. There is a method to my madness. By straying from the linear logistics of monoculture, my intention with this essay is to question the status quo. Rather than relying on existing thinking, we’re taking a step back, and analysing the system as a whole, to question its legitimacy. To simplify its infinite complexity: ‘queering’ is the subversion of normativity; it takes what exists and forms it anew. It is thus that we might approach the cult of monocultivation, and use this methodology to promiscuously queer it.