It is believed that fermentation was the first metabolic act.1 If fermenting organisms took the first bite, they’ve had a seat at the evolutionary table longer than our blip of a species can even comprehend. So why does society seek to sanitise itself of them?

Across viruses, bacteria and fungi, microorganisms often get a bad rep for the harmful diseases they can introduce. However, they’re essential to human life: from the bacterial exposure we receive when birthed,2-3 to the trillions of microbes that (an estimated 10 for every one human cell) that accompany us throughout our lives.4 Not only are they inwardly essential, but their outward nourishment has also formed our cultures as we know them. The famed anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss went so far as to suggest that it was fermentation which transformed us from natural beings into cultural ones, when early humans went from consuming honey fermented in a hollow tree; to fermenting honey in a hollow tree to consume.5

- 1. Tobin, A., Dusheck, J. (2005). Asking about life (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove, Calif.: Brooks/Cole. 389

- 2. Coscia A, Bardanzellu F, Caboni E, Fanos V, Peroni DG. When a Neonate Is Born, So Is a Microbiota. Life (Basel). 2021 Feb 16;11(2):148.

- 3. For children born via C-section, vaginal seeding—literally wiping them on the vagina—introduces these bacteria, helping boost their infant immunity.

- 4. 293. Pollan, M. (2014). Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. London: Penguin

- 5. Levi-Strauss, C. (1973) From Honey to Ashes. New York: Harper & Row. 473.

Though microbes have always been fundamental to human culture, we’ve only become aware of them relatively recently. The etymology of ferment comes from the Latin fervere, meaning to ‘boil,’ because of its once-mysterious bubbling. Then, in the 17th century, Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek’s microscope brought microbes’ miniscule lives into focus, and microbiology was born. However, it wasn’t until two centuries later, that Louis Pasteur—of pasteurisation6 fame—developed the germ theory, which suggests that microorganisms cause disease.7-8 Looking through the microbiologist’s lens, we now see that diseases aren’t visible to the naked eye. To fight what we cannot see, cleanliness is now understood as a preventative measure against disease, around which our cultures have now developed.

Yet our recent trend to over sanitise has inversely affected us. According to the “hygiene hypothesis”, an inexposure to certain microorganisms could explain the increase of a number of allergies in the 20th century. 9 Don’t get me wrong, I like my hygiene. But we’ve become so attached to our disinfectants that we’ve cleaned our body out of its natural immunity.

Technically, fermentation is an anaerobic metabolic process that converts sugars into acids, alcohols, or gases. It is, in other words, how microbes eat. This is a spontaneous reaction that can happen anywhere the conditions are right. But in our ultra-sanitised society, these natural processes are confined to sterilised containers, and inhibited from happening organically. Practicing fermentation reconnects us with the practices that formed our species, inviting a fecundity that stands in stark contrast to Pasteurianism.

- 6. A process used to kill certain pathogens by heat.

- 7. Ullmann, Agnes (August 2007). “Pasteur-Koch: Distinctive Ways of Thinking about Infectious Diseases”. Microbe. 2 (8): 383–387

- 8. Last, JM. (2007), “miasma theory”, A Dictionary of Public Health. Pennsylvania: Oxford University Press

- 9. Bloomfield SF, Stanwell-Smith R, Crevel RW, Pickup J. Too clean, or not too clean: the hygiene hypothesis and home hygiene. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006 Apr;36(4):402-25.

Fermentation takes on the notional context of a methodology. In this, what is just as important as the process by which it changes, is what it changes. Contemporary society functions on a set of normative ideologies. As we’ve explored, a “norm” is something “usual, typical, or standard”.10 Norms tend to refer to standard social behaviours developed from “rules that groups adopt to regulate and regularize group members’ behaviours.”11 Fermentation, as a way of thinking, can take these (often archaic) norms and reform them. It is important that this methodology doesn’t need the introduction of new material, because it means this can be done spontaneously.

- 10. ‘Norm’ , Apple dictionary.

- 11. Feldman, D. C. (1984). The Development and Enforcement of Group Norms. The Academy of Management Review, 9(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/258231

Cue post-Pasteurianism. On a physical level, post-Pasteurianism advocates less sterility in what we eat—within healthy, gut-friendly reason. On a notional level, it is the dismantling of the politics of purity and a diversification of social norms. Anthropologist Heather Paxson has used this as a framework to explore what she coined “microbiopolitics”. Built upon philosopher Michel Foucault’s notion of “biopolitics”,12 which studies governing bodies’ regulation of a population through policies around healthcare, reproduction and sexuality; Paxson’s microbiopolitics takes on a post-Pasteurian recognition that our microbial kin are just as likely to keep us healthy as cause us illness,13 recognising their influence over our bodies.

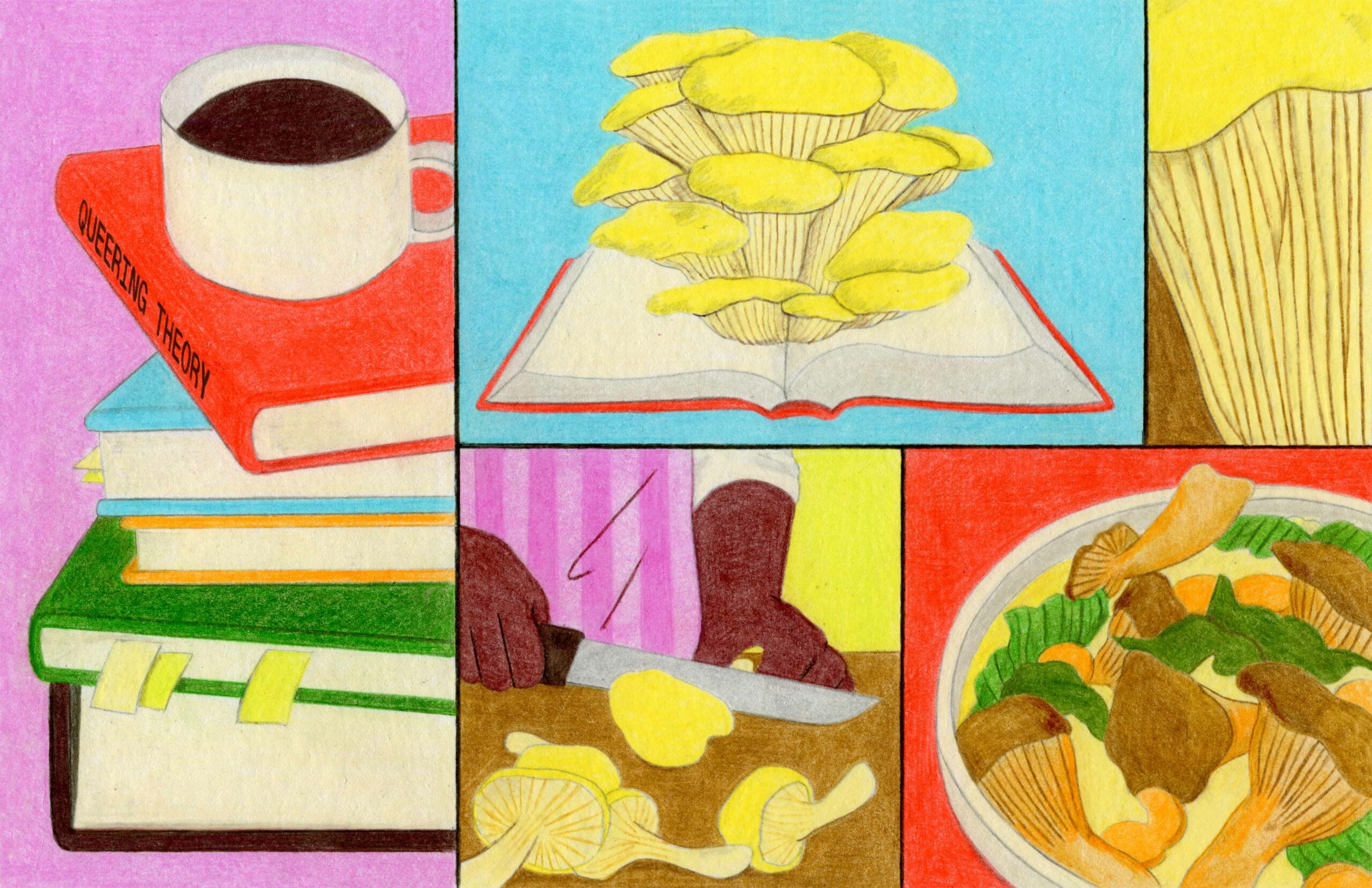

There exists a growing North American post-Pasteurian movement to reintroduce microbes into daily life which perceives fermentation as a political and ecological act.14 This movement’s maverick is the famed fermenter Sandor Katz, author of Wild Fermentation (2003[2016]) and Fermentation as Metaphor (2020). In his introduction to the former, Katz explains his devotion to fermentation, calling both activism and spiritualism which “affirms again and again the underlying interconnectedness of all.”15 Katz’s own introduction to ferments came around the same time as his diagnosis with HIV in the 1990’s. After retreating from New York to Tennessee’s Radical Faerie commune, a countercultural community, Sandor began fermenting with what he found in the garden, fermentation quickly becoming a process through which to mediate his relationship with the environment and his own body.16

- 12. Michel, Foucault (1975). Society Must Be Defended. pp. 241–244, 252.

- 13. The Gramounce ‘Food & Autonomy’. Accessed 17.04.2023

- 14. 293. Pollan, M. (2014). Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. London: Penguin.

- 15. xvii, Katz, S. (2003[2016]). Wild Fermentation. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- 16. xx, Katz, S. (2003[2016]). Wild Fermentation. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Katz’s fermentation revivalism goes against industrial food production by encouraging us to reconnect with microbes through food. Both his books go to lengths to unpack how fermentation can inspire widespread social change. Of central importance to his thinking is that, if we are to be mentally fomented by fermentation, we must also physically ferment. In other words, we must make ferments, thus co-creating with the microorganisms, and then eat them to understand the social change they can affect from within.

When diverse species work in unison like this, they reveal something intimate about the intricacies of their relationships. Mycologist Merlin Sheldrake speaks on the theory of symbiosis, in which “the association is far more than the sum of its parts.”17 On yeasts, Sheldrake goes on to suggest how yeast’s “transformational power blurs the line between nature and culture.”18 In our collaboration with them we also begin to blur these lines, shying from the normativity of dualist thinking. Evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis goes so far as to suggest symbiosis as the basis of life, rather than an exceptional quality of some organisms.19

- 17. 91-93, Entangled Life.

- 18. 229, Entangled Life.

- 19. The Gramounce ‘Food & Autonomy’. Accessed 17.04.2023

We’ve so far discussed the theory side of fermenting, so what about the queering? As the etymology “queer” suggests—as something “strange; odd”—it’s defined by its inadherence norms.20 It’s in this that queering aligns with fermentation. Both take something in existence, be it a thought or a food; deconstruct it; and then construct something new from the constituent parts.

In this series, we’ve explored this theme at length, not least in Challenging the Cult of Monoculture, where we sought a way to diversify singularity. To do this, we got tangled in non-linear linguistics on how the singularity of monoculture influences unilateral social thinking, leading us to queer promiscuity as a counter-methodology In this, the essay’s convolution became central, highlighting how non-normative approaches to information processing might inspire how we get out of our monocultured mess.

Here, this series’ thinking bubbles over, exploding beyond its bounds to reveal new and unknown forms. It is messy, fizzy, and hard to pin down; filled with fizzing ideas and overflowing thoughts. I find ferments a welcome reminder of my part in this world, not as controller but as contributor. In their potential to go awry, they remind me that they hold within them an infinite potential to change. In this, how they make is equally important to me as what they make. Indeed, I’d go so far as to say they influence my identity. Playing with the social norms which prescribe masculinity and femininity and everything within and without in a way that can have unpredictable results.

Despite—or perhaps because of—fermentation’s alchemical potential for the transmutation of matter, we’ve tidied it into clean, sterile jars, limiting its function on a culinary or chemical level. Refined down to single species to be stashed in sachets for our convenience ensures our control over it. Hand microbes some autonomy, however, and their subsequent ferments take on a whole new, more rowdy character. Out of the bounds of the sterilised sachet, they have room to move and groove, becoming boisterous, obnoxious and characterful. They burst out of bottles, make things you didn’t want them to, and sometimes outright refuse to comply.

Eating is believing, so let’s let ferments foment us. Co-creating a ferment with microbes is so much more than cooking. It is an act of radical resistance; of queer, inter-species care. We can learn so much from the ferments which formed us so let’s take a seat at their table.

- 20. ‘Queer’, Apple dictionary.