Vitality quietly emerges in overlooked spaces—challenging us to rethink foraging beyond expected confines, beyond the familiar. How can foraging be a transformative practice, unearthing potentials for connection in our landscape, with our food, and with each other?

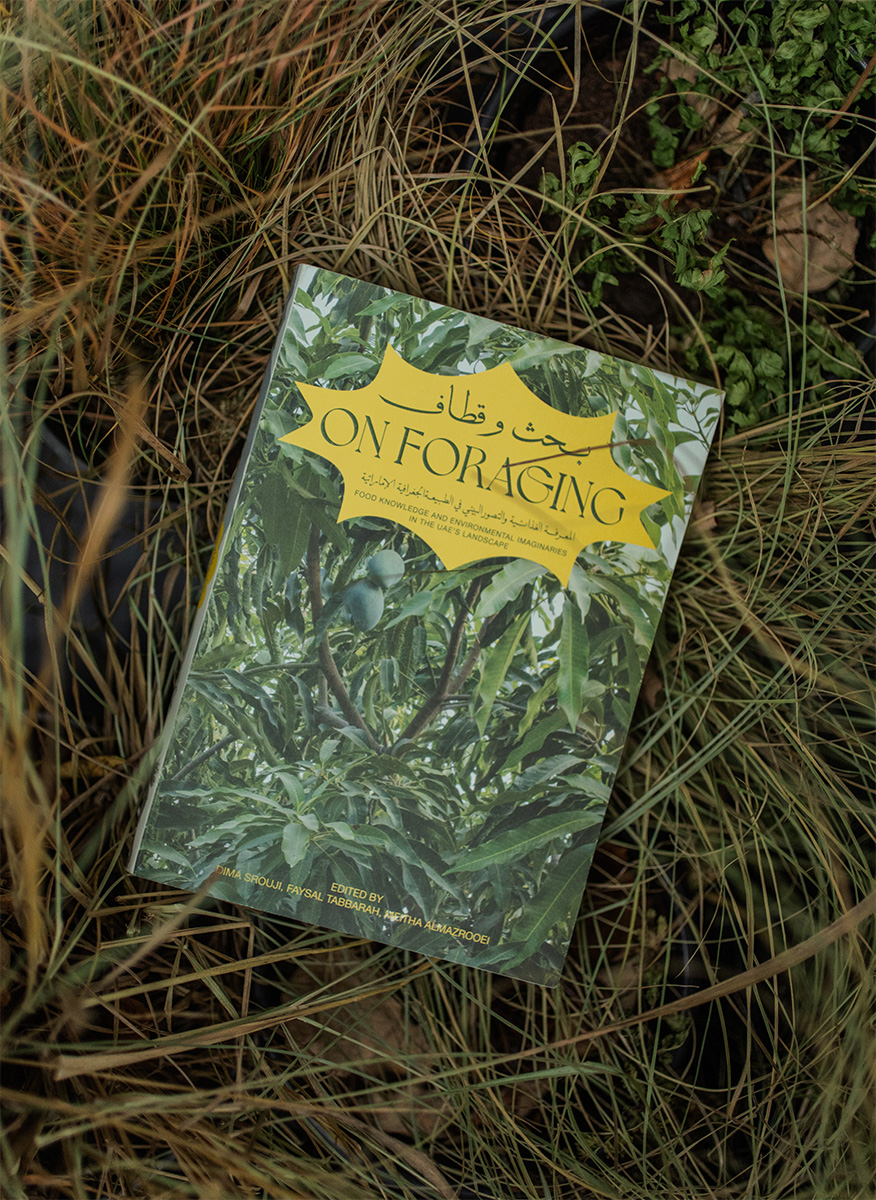

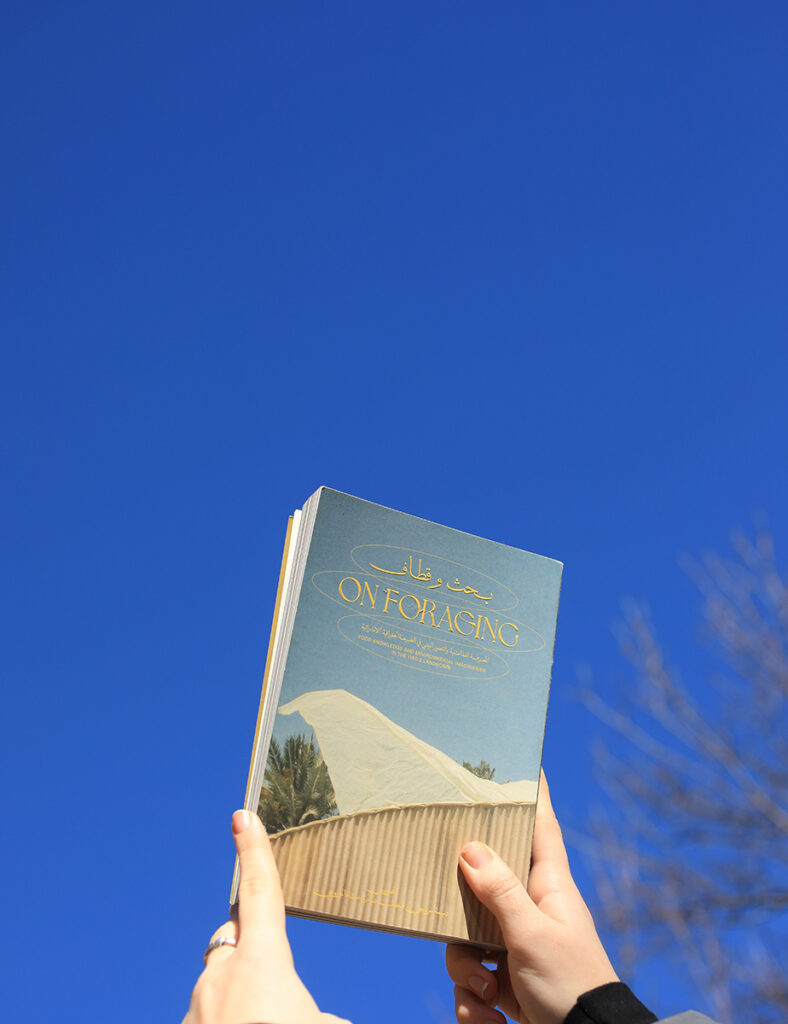

A companion to and continuation of the 2020 exhibition at the United Arab Emirates Pavilion at Expo, On Foraging surveys the intricate history and contemporary significance of foraging practices in a region classified as “other land” by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “It is as though they either do not exist or do not necessarily warrant dedicated scientific study, effectively rendering them as unproductive, desolate landscapes” (11). The editors, Dima Srouji, Faysal Tabbarah and Meitha Almazrooei, introduce this project as an act of foraging in itself; poems, photographs, interviews, and essays are layered into the book; it is an index of stories from the land and the pursuit for nourishment upon it.

Turbo, an Amman-based design studio led by founders Mothanna Hussein and Saeed Abu-Jaber, crafted the visual identity and layout for the exhibition and book. The studio produces political posters, editorial and branding projects, community events, and runs Radio alHara. In our interview, they discussed their design practice and inspiration.

Rejecting the common practice of treating Arabic as an afterthought, Mothanna and Saeed intentionally centralize it. “Very fetishized by the West and shunned by the people here, [we] focus on the Arabic language as part of the local […] because we are from [Jordan], and because the [Arabic] type gives you way more play area than the English alphabet,” TKTK explains. “Arabic was always thought about last, and usually made by cutting up English into bits and pieces and re-forming from English letters. We hated that.” In the context of On Foraging Turbo carefully navigated pairing typefaces for visual coherence and created a balanced and organic bilingual layout.

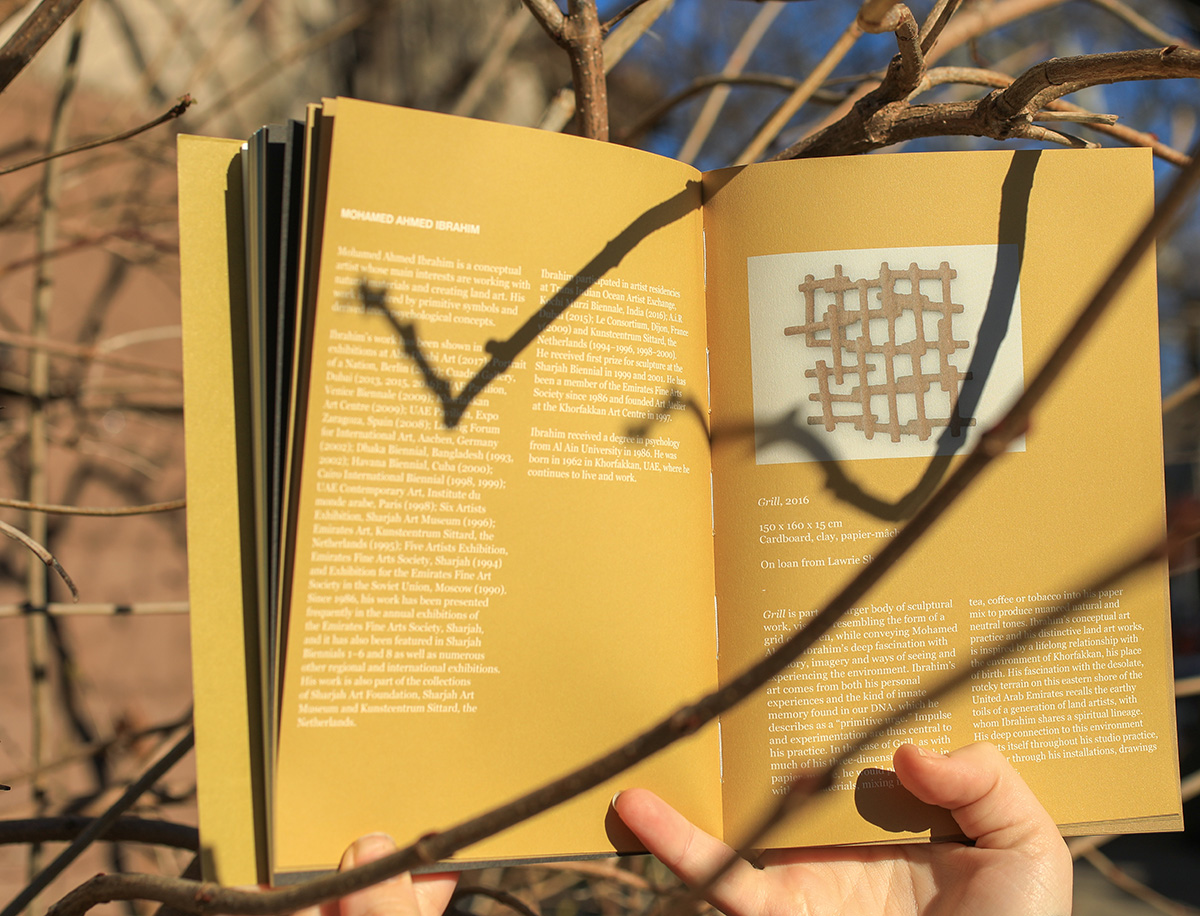

Mothanna and Saeed shared that their creative choices often incorporate an element of fun; the graphics of fruits in the book act as “palette cleansers,” breaking up dense text and establishing a visual rhythm that echoes the contrast and play between more poetic and research-based sections. They also highlighted the resonance between Jordan’s arid environment and water scarcity issues and the book’s themes, which brought interest and impacted their design approach. “The process of foraging is also the process of learning how to see and comprehend each specific environment” (36).

This idea materializes in an essay, written by architects Hamed Bukhamseen and Ali Karimi, on fishing weirs or hudoor, a three-thousand-year-old practice of fish trapping in the region. They discuss this apparatus as deeply entwined with the environment, thriving in a symbiotic relationship between land and sea. While this liminal space has been historically disregarded, local knowledge teaches that this is an active, fertile place for cultivation. Sundar Raman later writes: “The forager’s skill is in tuning into the language of nature” (36). Such comprehension can mean adapting design to cohabitate with the surrounding environment.

The term “architects” takes on a more conceptual dimension in the collective work of Faysal Tabbarah, Meitha Al Mazrooei, and Dima Srouji, the editors of this book. Much of their work deals with architecture beyond physicality and functionality, embodying the changing dynamics in culture.

In particular, Dima Srouji’s practice as a Palestinian artist and architect: “explor[es] the ground as a deep space of rich cultural weight. Srouji looks for potential ruptures in the ground where imaginary liberation is possible.”Examining foraging through this lens, the practice becomes a repository brimming with stories, histories, and futures ingrained in the landscape—Srouji’s work and On Foraging prompt one to see foraging as an active, living artifact.

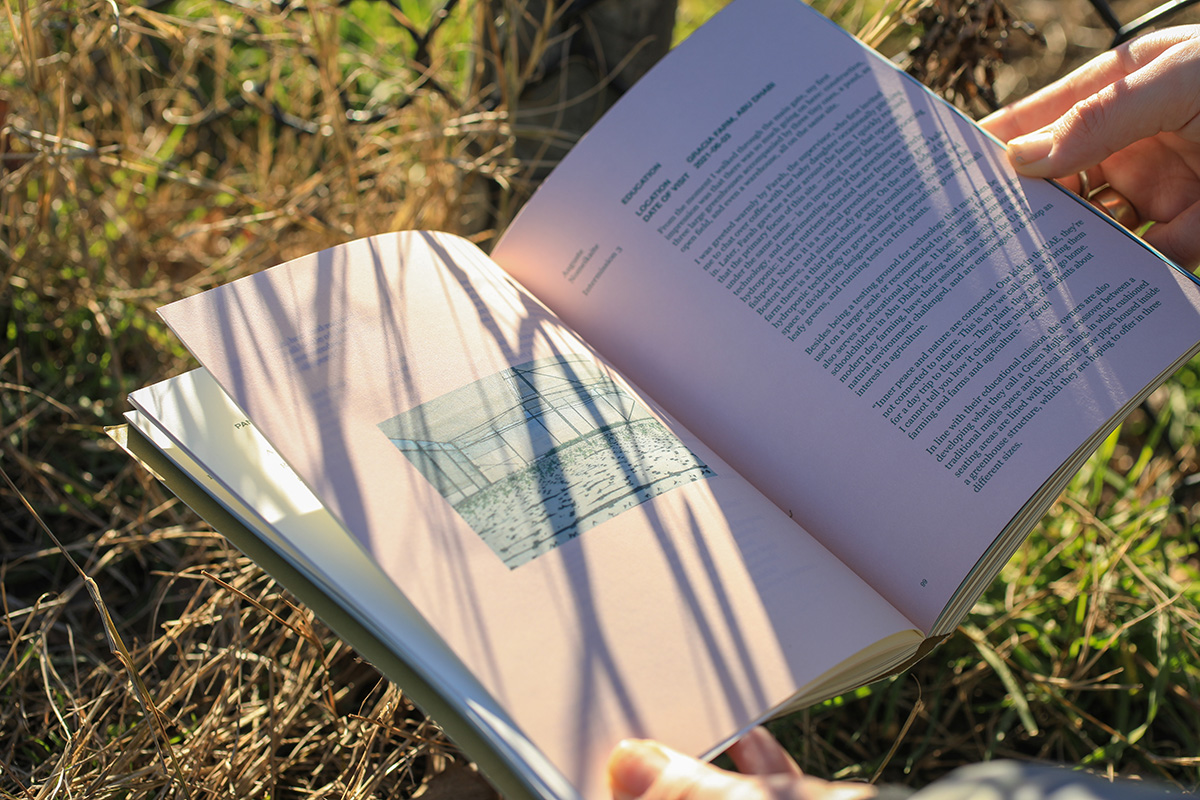

This perspective raises questions about the role of food and how it can serve as a tool of resistance while also for erasure. Throughout history, and examined in this book, food has been wielded as power in geopolitical contexts. For instance, Dalal Musaed Alsayer writes on industrialized farming infiltrating the UAE, often heralded as “progress” but consequently altering the region’s eating habits. ”Geography, climate, and locality do not matter in the global race towards universal nutrition. Equally, architecture thus becomes a container, holding everything inside, irrespective of the outside. Like other ‘markers’ of development, the typical Western farm replaces centuries-long agricultural and spatial practices.” (32) Considering stories of colonial violence and dispossession, the loss extends beyond the tangible; it encompasses the erosion of narratives, knowledge about the land, and traditional food practices, resulting in the erosion of cultural identity. On Foraging offers a framework that positions the preservation of knowledge and the act of foraging as a means of liberation and solidarity.

Dalal Musaed Alsayer“Geography, climate, and locality do not matter in the global race towards universal nutrition. Equally, architecture thus becomes a container, holding everything inside, irrespective of the outside. Like other ‘markers’ of development, the typical Western farm replaces centuries-long agricultural and spatial practices.”

How can ecosystems and architecture work as archives of these stories? In the book, Auguste Nomeikaite’s reflection on visiting a family-owned farm and their intercropping, a practice of allowing plants to grow together, illustrates this: “I could not help but marvel at the—literally—layered history of agricultural areas in the UAE. On the one hand, it made me curious about the practices that had not been documented; the stories that have been buried. On the other hand, I reflected on the jungle-like images of those greenhouses and the nearly self-sufficient small scale ecosystems that can be created by letting plant species coexist” (64). Preserving these practices nurtures resilience against the homogenizing forces of the globalized agricultural industry.

In the footsteps of this practice, foraging serves as a means to roam, revitalize, and celebrate each distinct landscape. For New Yorkers, perhaps it looks like a community fridge, caring for the tree well, preserving seeds, and collecting recipes. It can be a helping hand or a welcome glance. “Our contemporary cityscape is a combination of the planned and unplanned, in a complex relationship with the natural environment” (37). Searching the thresholds where built and natural environments converge invites us to challenge our ways of seeing and seek sustenance in these liminal spaces. In Bukhamseen and Karimi’s essay, they reference the traditional Islamic law of “right to use,” where land ownership is contingent upon active cultivation. This invites contemplation on how modern capitalist policies shape stewardship of the land and, ultimately, the dynamics between food and community. Though city living can be transient, we can consider how to better invest in, cultivate, and “root ourselves” in our local landscapes.

This book serves as a guide, encouraging us to view foraging as a vehicle for both self-sufficiency and collective empowerment. Foraging means relearning to notice because we must. “Foraging is, and will always be, an essential source of our food, our medicine, and most importantly, our sense of who we are. Indeed, without foraging, we may well be nothing” (37).

- Edited and introduced by Dima Srouji, Faysal Tabbarah, Meitha Almazrooei.

- Contributions by Rohit Goel, Frank Ruda, Mays Albaik, Ala Younis, Isaac Sullivan, Veeranganakumari Solanki, Rico Franses, Mona Al Jadir, Mays Albaik.

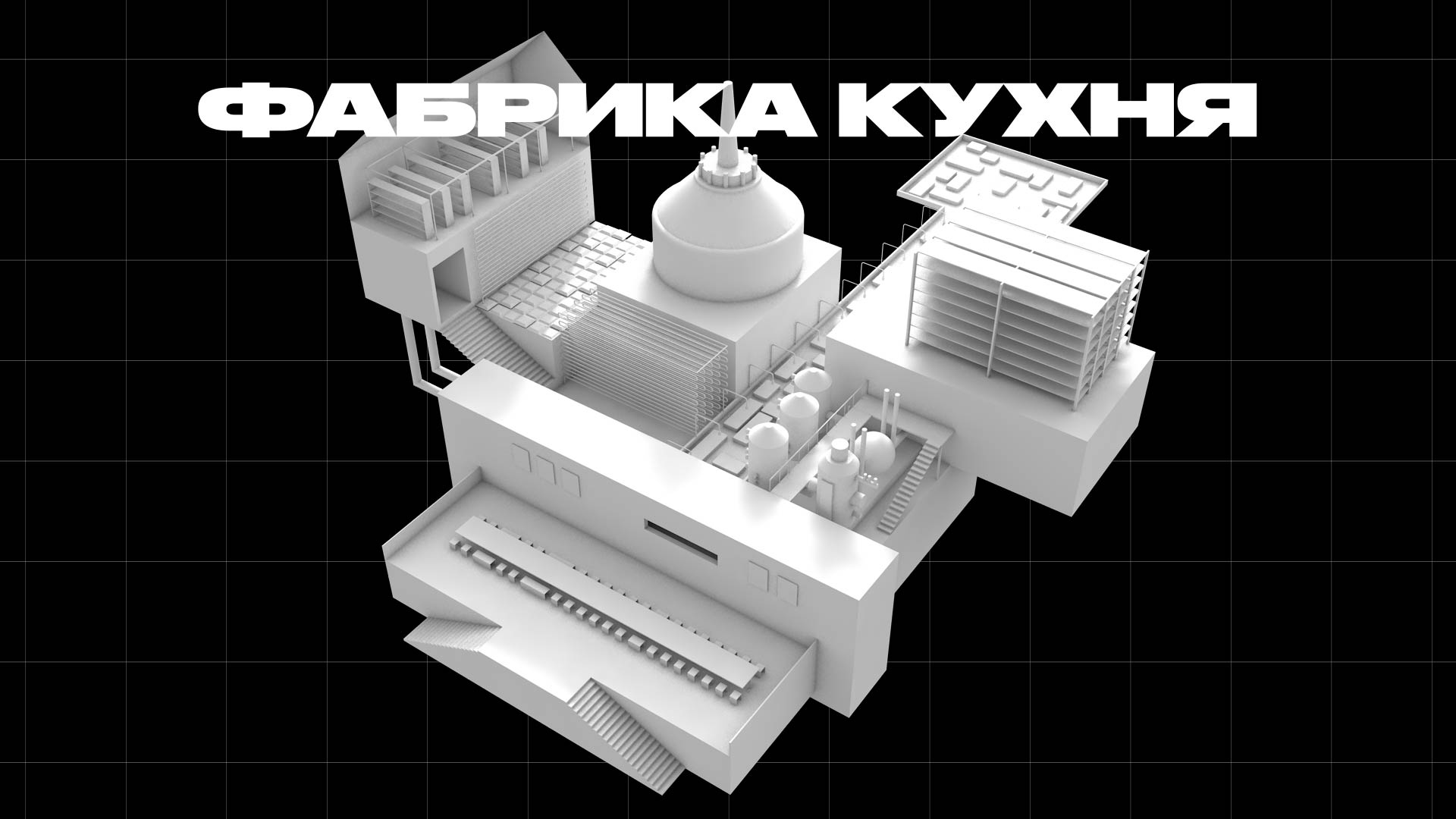

- Graphic design: Turbo.

- published in February 2023

- bilingual edition (English / Arabic)

- 15 x 21 cm (softcover)

- 352 pages (ill.)

- 40.00 €

- ISBN : 978-614-8035-50-0

- EAN : 9786148035500