“Across the olive-growing world, the tree is translated by terroir and enacted by culture,” writes Louise Long, the founder of LINSEED Journal in the introduction. Focusing on a single ingredient in each issue, the journal traces entangled histories of labor, craft, and heritage, mapping a comprehensive web of food as expansive material. Published in April 2024, this edition explores the olive as the form of food, ritual, power, poetry, and identity. LINSEED follows the unique physicality and cultivation of the olive across time and regions. It illustrates food as a form of place-making, a vessel for tales of each distinct landscape and its stewards.

Louise Long, with a background in photography and writing, had envisioned starting a publication for a while, but it really came to fruition during the pandemic, she explained in an interview with MOLD. Passionate about food justice and local food growing practices in the UK, she believes storytelling is a compelling tool in resisting monocultures and in forming more sustainable agricultural practices. With an extensive open call bringing in a wide breadth of collaborators for each issue, the theme guides the content but each story offers an unexpected and abstract take on the subject. As Lousie asserted, “It’s really this jumping off point into very diverse forms of writing and art making, and different ideas from craft to horticulture to travel, food history, science. The idea is that we’re really trying to draw cultural connections between them. So there are all these hidden links.”

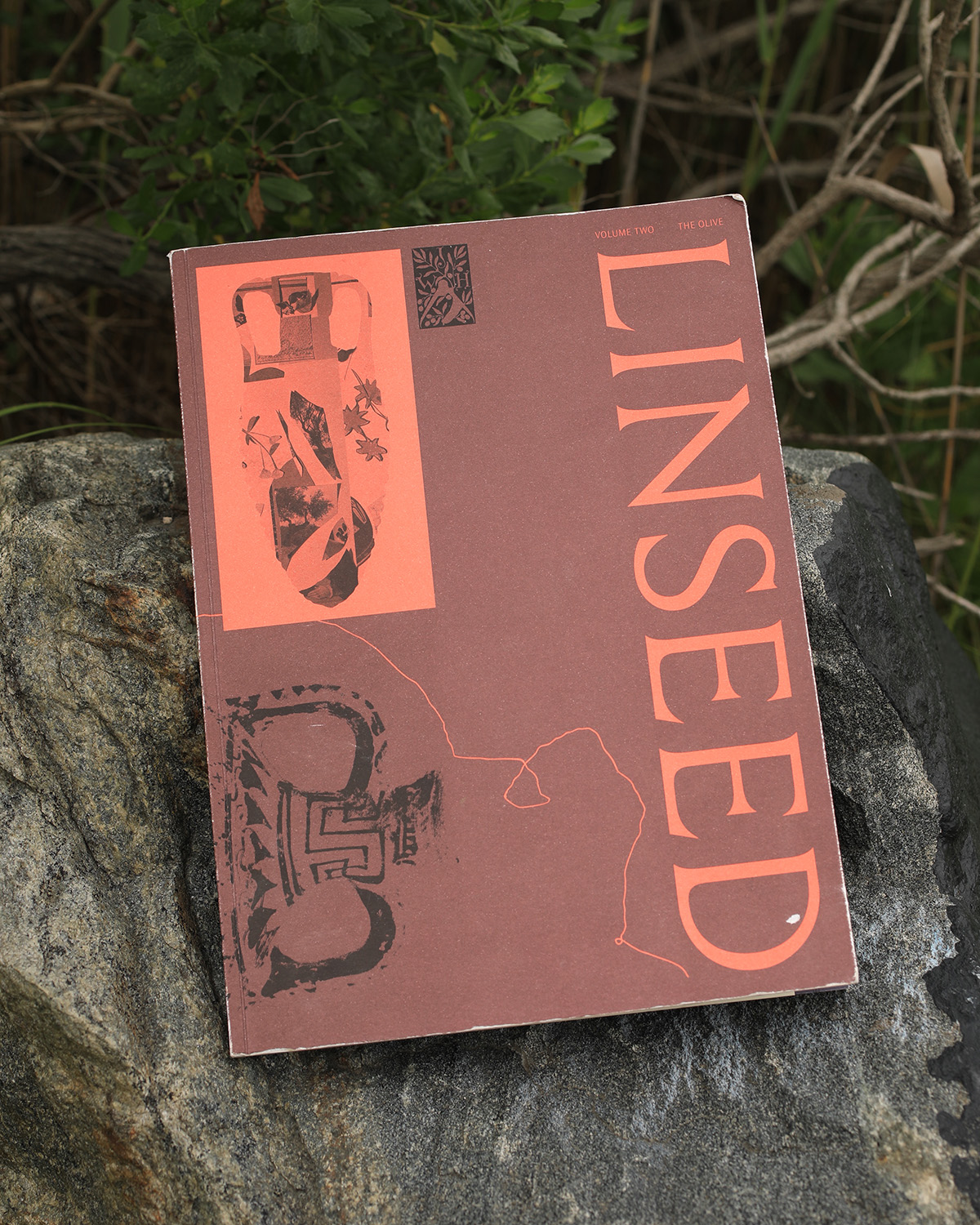

Constructed by Louise and the editorial designer, Émilie Loiseleur, the cover’s collaged fragments of contributed artworks and drawings bleed into a map of the olive’s global movements on the inner cover, and signifies a connectedness. Louise explained that the design and content should reflect a deep sense of place for each piece. Each contribution, whether overtly or subtly, speaks of its origin.

The journal is thematically and aesthetically divided into four chapters, each mirroring a stage of processing linseed into linen. Louise explained this decision, noting that the “[linseed plant] is a spring point into creativity, as well as food culture. Its at the intersection of nature and land and culture and cultural symbolism: It’s a plant and it’s cultivated as food and fodder for animals, It makes linen, which is one of the oldest textiles in the world, it goes into oil paint, and gets used in linoleum floors.” The journal follows not only foodways but also explores the oft-overlooked yet culturally significant uses of food materials, such as the olive’s role as a color for uniforms and as a motif in ancient stone-reliefs and engravings.

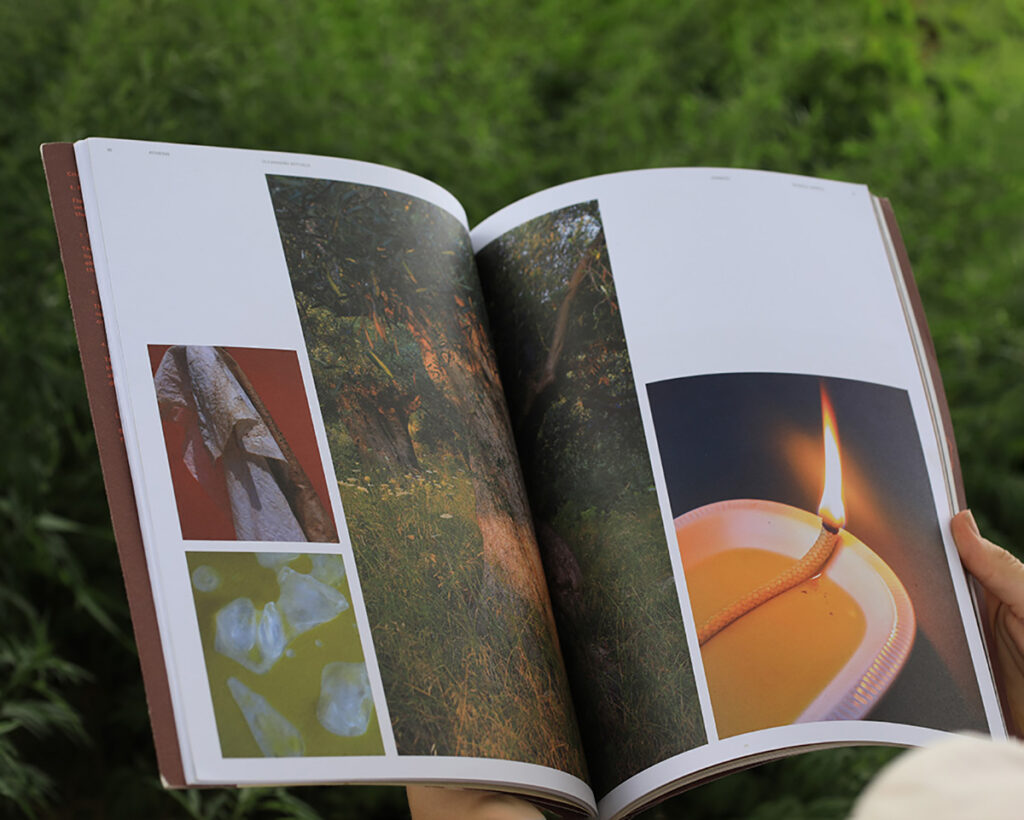

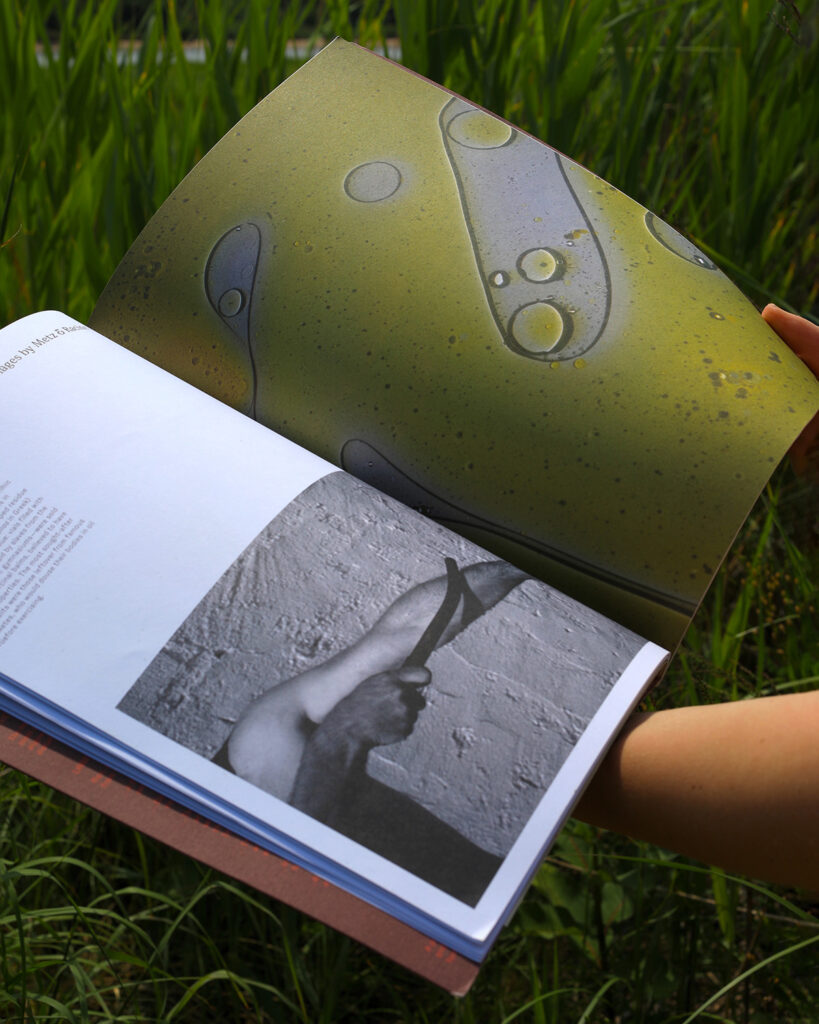

The first chapter references the harvest bundling process, Louise described, with color and tone designed to resemble bundles of flaxseed stems and the contrasting images representing the “stress and graft of process” and inspired by midday summer heat. Chapter two explores the retting stage, where fibers are soaked in water and rot. It highlights “materials, duration, responses to place, ideas of landscape and resources, the idea that you’re really intertwined, immersed in the land.” Inspired by the breaking and hacking process, the third chapter has a lighter and dusty paper quality, “as if you’re in the workshop undergoing that process.” The final section covers the combing and spinning process, which is typically done at night, it is more contemplative and has to do with “tradition and ritual and the almanac, coming to the end of the year, aligning yourself, the next stage, beginning, again”.

Echoing this format, LINSEED investigates the olive as shaped by its production, through touch and labor. “I’m really interested in the idea of process: craft process and creative process and the idea of the journey of getting somewhere.” Louise explained.The material’s meaning evolves based on time and cultural practices and the journal traces this transformation from material into the edible ingredient we interact with today.

Inextricably tied to land and labor, the olive is explored as identity. In Palestine, it is both symbolically and physically a representation of steadfastness. Fiona Dunlop, a food writer, shares a quote from farmer and cook Mona in Nablus, whose family—like many others in the region—own groves but continually struggle against encroaching Israeli settlements: “Olive trees have more than just economic value. They are part of us and of our history” (87).

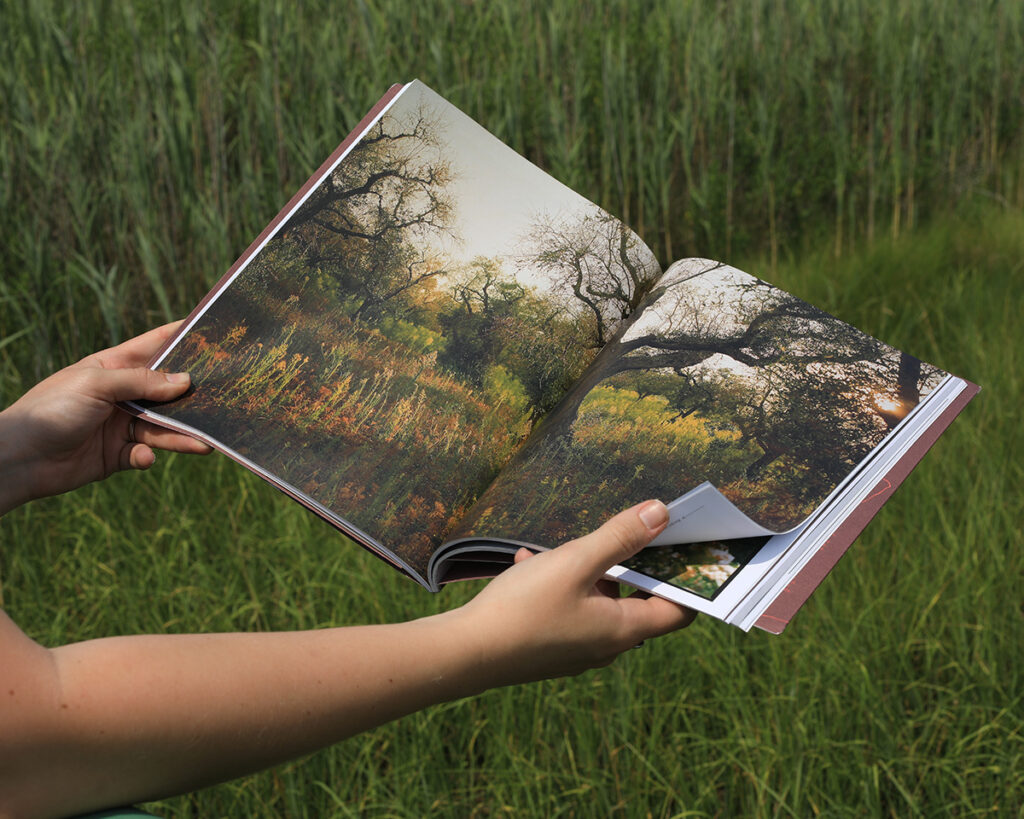

The continued resilience of the olive stands as a testament to its stewards and LINSEED records ancestral practices as a form of preservation. Agricultural methods become ritualized and people align with the timing of processes, such as harvesting olives for pressing by sunset. In the groves of Sardinia, Letitia Clark poetically portrays the olive harvesting process for oil and its profound impact on daily life. She reflects, “Olive picking dissolves the sense of now” (60). “The silvered fronds of the olive stitch together our lives, and the cycle will go on—forever and ever, I hope, without end” (62).

The journal emphasizes the connectedness between organic material histories and futures. Letitia Clark describes the olive’s taste as “almost prehistoric,” marking how engagement with food connects us to its past and the tapestry of experiences it embodies.

Louise remarked: “I want to draw connections between places and forms of creativity and ways of being in the world also through ancient landscapes and ancient cultures, and look at them through the prism of contemporary writers and makers and producers. People seem to be excited about ideas of mythology and folklore and language, ancestry heritage, these are kind of preserved, because they’re seen through a modern lens, or they’re presented as part of contemporary thinking, in a way that feels like a most productive way of preservation […] It’s actually continuing to look at it as a form of contemporary life. And that could be anything from a method for grafting trees, or a form of textile art. There are so many traditions that we see circling back and being presented as kind of new, but actually, if you then look at them as having this fascinating, weaving history of politics and all of the people, then it becomes so much more alive.”

This edition includes a consolidated section of recipes that tie into other narratives in the edition. Inspired by old recipe books and handcraft, the design of this section pushes for the de-commodification of food material.

If the endpoint is the jar of olives or bottle of olive oil in our local grocery store, LINSEED forages for the relationships and processes that get them there. With both perplexity and tenderness, it resists the alienation of the food we eat from its origins and the homogenization of food material.

One of the final pieces in the journal’s second issue deals with poetics of the olive as reconciliation, exploring its complex meanings: peace, rootedness, renewal, but also the lesser acknowledged, power and resistance. Contributing writer Julia Merican articulates these ideas, writing “During reconciliation, the olive branch is an act of extension. An act far from passive: requiring movement and action. In many cases, this effort carries a generosity and optimism, akin to an apology or even a call for forgiveness. […] But if gestures are not followed-up by actions, the extension of an olive branch is merely performative. Symbols can survive in the background of culture, but their strength of meaning hinges on usage: on committed action.” (94)

To contemplate this idea within the broader context of the project is to extend one’s curiosity about food material to their deep political and historical meanings. LINSEED, as a practice of connection and meticulous observation, weaves a meandering and imaginative narrative. It embraces and evolves, as the material does, in the process of becoming.

Published April 2024

330 x 240mm, vegetable-based inks and carbon neutral printing.

Creative & Editorial Direction: Louise Long; Design: Émilie Loiseleur

330mm x 240mm