The sounds of domestic labor reverberates in the music room of Konsthall C. a space designed as a “public work of art, an urban renewal project, and an art institution” in Stockholm, where the public program and research project, Home Works, rooted for two years. Using only kitchen appliances and other found objects, a group of children from the surrounding area gather for a workshop to forge instruments and play in unison, taking notice of their environments, experimenting with forms of non-linguistic communication, and reflecting on what home means to them.

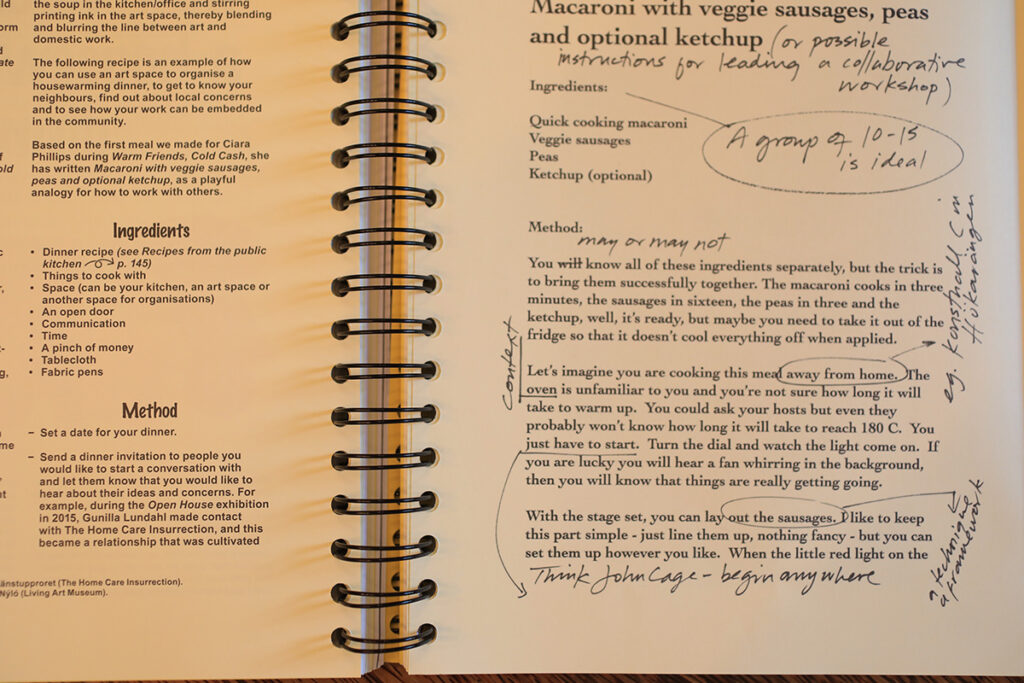

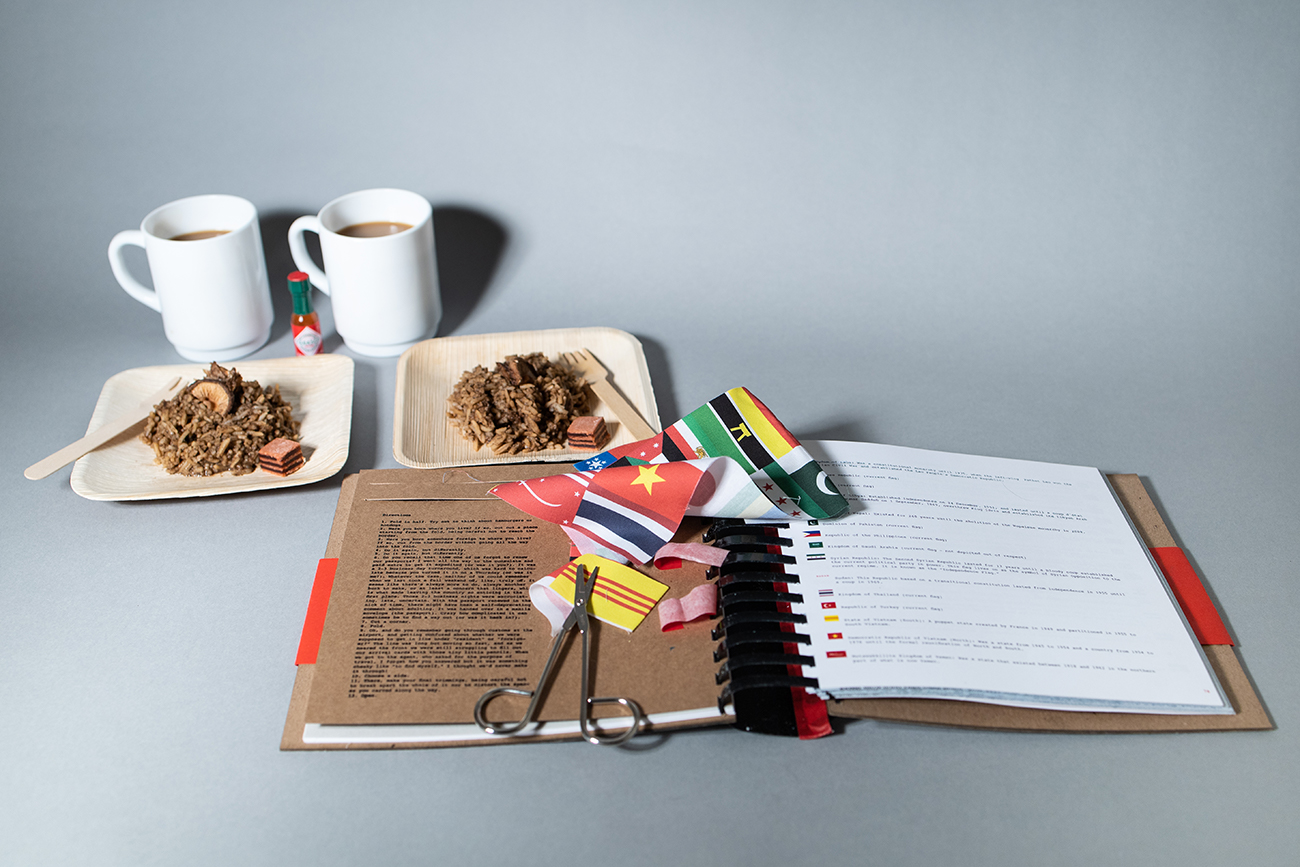

(Home Works): A Cooking Book is born from the program co-directed by Jenny Richards and Jens Strandberg and developed with Anna Ahlstrand, which welcomed the local community to freely cook, share meals, do laundry (amongst other tasks) and participate in a series of workshops and exhibitions in the space. The book stands as both an archive and blueprint for it’s adaptation. Distinguished by the title in parentheses, designed in a typeface referencing the original Konsthall C. font, and a sunny, spiral-bound build, the book signifies the project’s transient nature and balance between temporality and continuity. Self-identified as a “curatorial cooking book,” it uncovers the hidden labor, offers retrospective critiques, and provides a roadmap for similar projects elsewhere, urging readers to experiment and adapt the provided recipes in their own contexts. “(Home Works): A Cooking Book” holds a robust body of research and feels like a form of art, adapting the concept of a recipe book by embedding within it a tapestry of interactions, histories, and labor, presenting recipes not as static instructions but as dynamic processes.“Here, we gather this knowledge and the methods we learnt in the form of recipes, so you can try to cook up your own situations of collectivity today” (5).

(Home Works) repurposes the “recipe” as a process to cultivate new relations.

The instructions for both workshops and meals in the book capture distinct conditions that one must seek out in their community, landscapes, and local environments. The book details workshops taught at Konsthall C, such as the manifesto-writing led by artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, where participants shared their daily at-home tasks in groups, created corresponding emotional scales, desired changes to these routines, and finally a manifesto, with ingredients such as an “open mind and willingness to see and examine the details of our lives” (48). In another workshop, the methods read: “Could you invite your neighbors to your home for coffee or dinner? Can this start a conversation around how other people understand what home is?” (137) “What food will you prepare? Cooking with others can be more fun. New ideas, untold stories, and local histories surface through conversations, and when cooking together you can talk and share the labor of preparing food” (161). These exercises encourage participants to take careful notice of their own work that may feel otherwise naturalized.

A recipe is versatile; it can and should be adapted, shared, and evolved over time, to be rethought, rewritten, and re-cooked in the readers’ own context. Philosopher Jonna Bornemark emphasizes in an interview in the book that recipes and manuals cannot stand alone; practical knowledge is gained through learning and doing (129). The meaning of a recipe is often derived from the ways in which it is realized. Information is passed down through relationships, which most commercial written recipes cannot and do not immediately communicate. The labor embedded in foodways is ever-present but not necessarily translated through text. Bornemark argues that this idea extends to any context of building resistance to neoliberal systems. Spaces for resistance must allow members to “explain their practical knowledge in relation to everyday concrete experiences” and learn how to “express resistance when there are no words to describe it,” with active listening and finding new ways to listen being crucial to building alliances, and therefore making change. (132)

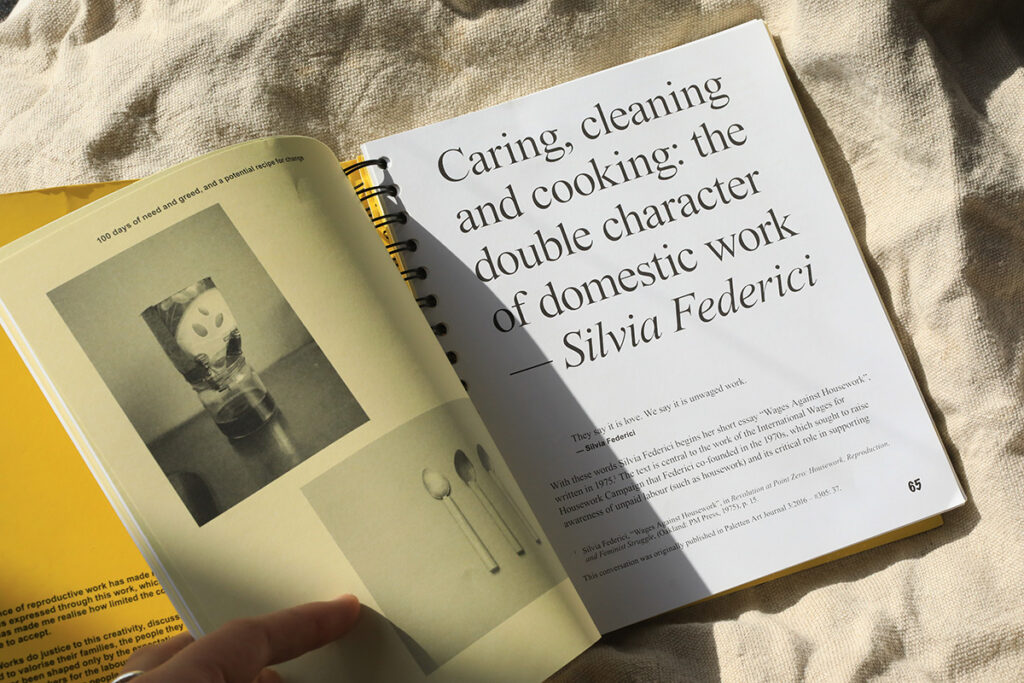

At the heart of the Home Works project lies a reevaluation of reproductive and domestic labor.

The book challenges its undervaluation, alienation, and intended invisibility under capitalism. Silvia Federici’s influential 1975 essay “Wages for Housework” and the inspired campaign lay a groundwork on issues of unpaid labor, serving as a significant point of reference for Home Works’ book and program. The home, where this work is most often performed, is reconceptualized as a site of struggle and an opportunity for communal interaction and solidarity. Through shared cooking, chores, and art-making, participants engage in dialogue, unraveling traditional domestic dynamics and empowering those to shape their own experiences. The editors reference Federici’s argument that wage defines how work is valued, highlighting it as a point for reconsideration. “Central to Home Works was understanding the relationship between the home, the labor performed there and how this connected to wider feminist and anti-capitalist struggles. The programme wanted to explore the politics of domestic labor and challenge the general understanding that domestic work was separate from the reproduction of capital, and how that could inform the workings and running of an art space […] the programme aimed to show how our intimate environments—our homes, kitchens, and bedrooms—are not suffering from capital, but instead are suffering from ‘precisely from the absence of it’. Capital will never be dismantled if we accept the view that our kitchens and bedrooms are separate from the reproduction of capital” (34).

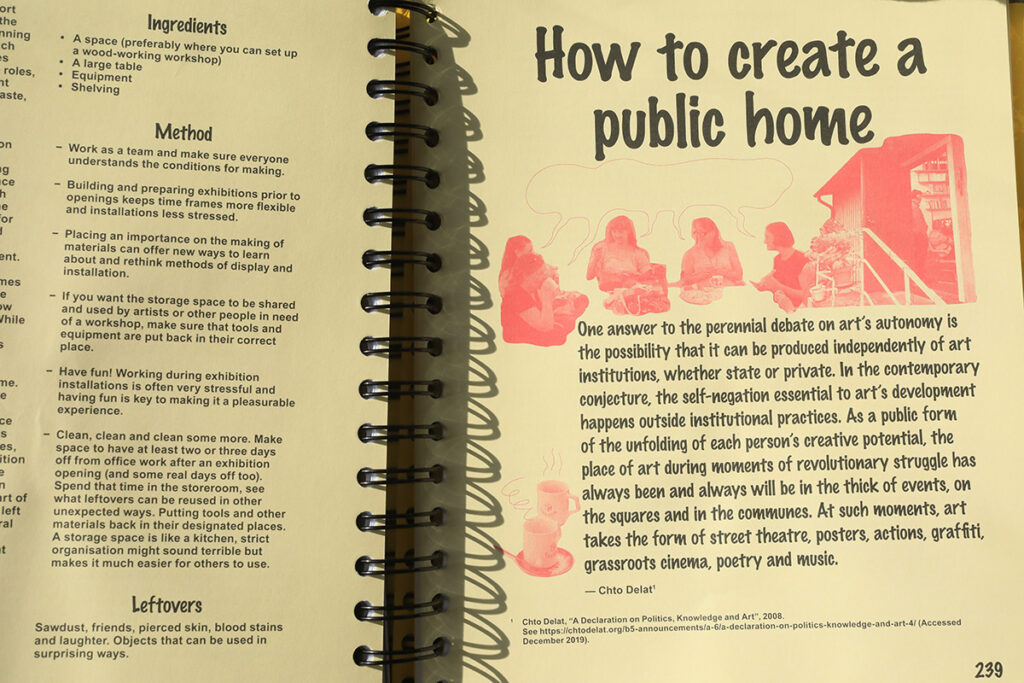

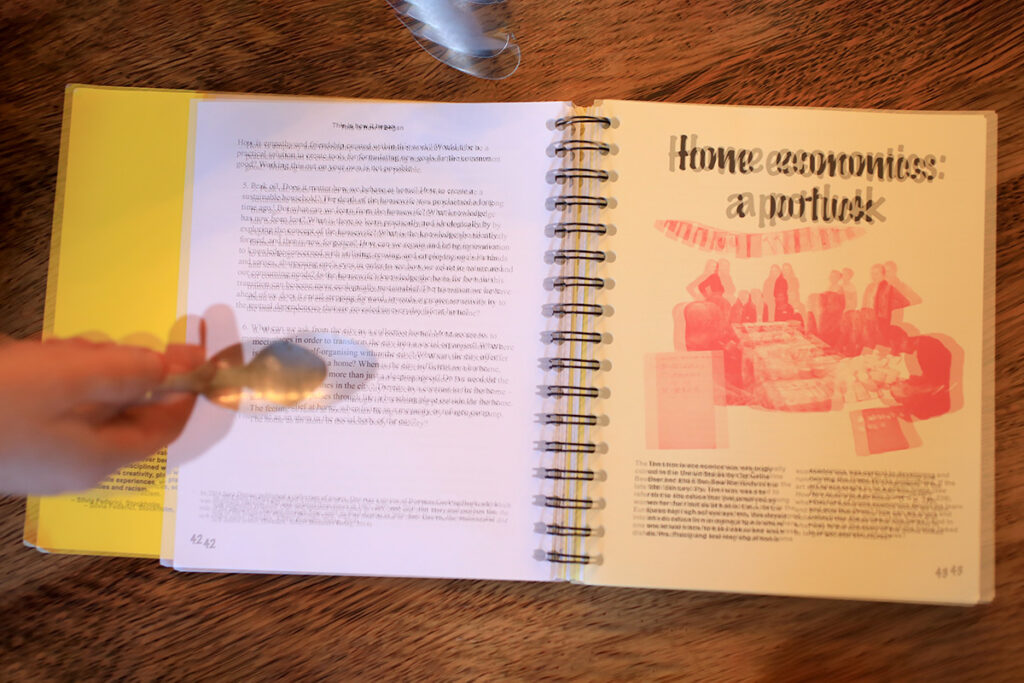

The books reflections on the public home program restructure the often rigid concept of “home” entirely: where it can be found, how it can be shared, and what can be created from it. Federici describes in an interview with Home Works that the struggle for change must encompass the reclamation of space and resources, emphasizing the importance of spatial dynamics in organizing efforts: “Our struggle must include the re-appropriation of space. Struggles need an infrastructure of space and resources” (170). Embedded within spatial reconfiguration is a transformation of traditional domestic dynamics, such as those between hosts and guests. Collaborating journalist Gunilla Lundahl discusses in the book that unexpected yet familiar spaces can serve as participatory environments that connect rather than separate. “What can we ask from the city as a collective home? More access to meeting places in order to transform the city into a social organism? Where is there a place for self-organizing within the city?” (42)

Food’s transformative power is central to the book’s ethos, serving as a tool for nourishment, activism, and liberation.

Emphasizing communal dining experiences and providing loose, adaptable recipes, (Home Works) underscores the importance of gathering in art and political organizing spaces, with food as a vehicle for doing so. The book posits that eating together is an act of cultural exchange through experimentation, conversation, and communal work, which is a practice of solidarity and shapes embodied knowledge. The recorded recipes engage these gathering experiences in new ways. “Manuals and recipes are one way to gather and save experiences. […] Recipes that in themselves can be brought into new intellectus1 reflection and new specific contexts and situations. In this way, recipes are tools, which outline important insights that we want to share. This is how I think recipes and manuals should be used. That said, an important philosophical question lies behind the production of recipes and manuals, which has to do with the relationship between generalization and specificity. Humans often move between these, and it is in this movement that problems arise, since we tend to forget the point of what we are doing” (129).

- 1”Intellectus is the human capacity to stand in relation to horizons of ‘not knowing’ and explore what is important to and how” (Bornemark, 126)

(Home Works) draws attention to similarities between participatory art practices and shared dining experiences, and that food involves all our senses, facilitating moments for connection and negotiations with art, our direct communities, and nonhuman species. Fedrici asserts: “the struggle over food, then, implies much more than the question of food itself. It also implies the continuity between us and the earth, the animals, the waters. Food connects us to a complexity of relations none of which can be ignored. For me, thinking of food in cultural and ecological terms is to go beyond the periphery of our skins. Our bodies are not self-enclosed; our skin does not set the frontiers of our relation with the surrounding world. Our bodies are porous. They extend and continue into the surrounding environment. They respond to and connect with other bodies. Food brings this reality to us in a very concrete way, we are made of the food we eat, but the food comes from the earth, the trees, the air and the labour of other human beings. Out of food we can expand our perspective into interlocking universes continually merging into each other” (169). The most fruitful part of cooking and eating may be an awareness and appreciation for the shared experience.

(Home Works) challenges conventional notions of materiality.

In the pursuit of connecting with one’s environment, the book advocates for a mindful relationship with matter and the transformative potential of repurposing. Their curatorial approach, as articulated by the editors and co-directors, emphasizes: “[the ingredients] are discovered through gathering resources and forging relationships, becoming familiar with people, spaces, and interests in your community” (37). Every material holds significance; it doesn’t necessarily have to be revolutionary. “Rather than categorizing materials as primary or secondary, view all materials as equally valuable and in need of being incorporated into the main mixture at different stages, or composted to enrich the soil and nurture the growth of new ideas. Given the long-term nature of this process, leftovers generated along the way can often find new purposes in other recipes, enabling established collaborations and artistic relationships to evolve and be integrated into different aspects of the research” (37).

In the context of reproductive labor, materiality encompasses both maintenance and preservation, as well as the concept of renewal. Jonna Bornemark delves into this notion in the interview within this book, stating, “To maintain a thoughtful relationship with material is, to me, inherently political. In today’s culture of consumerism and mass production, our connection to material is often obscured. We tend to fixate on what we lack, and once acquired, it swiftly loses significance. However, how do we attune ourselves to the material surrounding us and cultivate meaningful relationships with it? Establishing intimate connections with material transforms it from mere objects into relational entities” (133). For instance, repurposing kitchen appliances as musical instruments not only brings joy to seemingly mundane items but also prompts a deeper engagement with the material and its broader implications.

While the Home Works program initially took shape within a physical space, its principles extend much further.

The book anchors the program’s core ideas and metaphorically composts the experiences. Encouraging us to apply these lessons within local contexts, (Home Works) is a framework for seeding community within the structure of our everyday routines. It urges us to expand and share our embodied knowledge as a radical opposition to oppressive, market-driven systems. Echoing Federici’s concept of “joyful militancy,” the book emphasizes the belief that communal activities like cooking, dancing, and art-making propel political movements. The work may be light, playful, and familiar. The book proposes the notion that home-work is an act of world-building, with each exercise inviting readers to contemplate alternative ways of shaping these worlds. As we explore the traces of experience within our food, material, and spaces, we deepen our understanding of their inherent political implications and the opportunities to construct mutual care at home, whatever shape that may take. Through experimentation, we may lessen the grip of these systems by making public and doing in community what may usually be confined to solitude.

Typesoftcover with Wire-O Binding inside

Dimensions185 x 230 mm / 7.3 x 9 inches (portrait)

Pages280

ISBN978-94-93148-37-6

Editor: Jenny Richards, Jens Strandberg

Author: Samira Ariadad, Jonna Bornemark, Marie Ehrenbåge, Silvia Federici, Sandi Hilal, Dady de Maximo, Temi Odumosu, Jenny Richards and Jens Strandberg, Khasrow Hamid Othman, Halla Þórlaug ÓskarsdóttirGraphicJohnny Chang and Louise Khadjeh-Nassiri, based on the Home Works graphic profile by Maryam Fanni and Rikard HeberlingArtistStephan Dillemuth, Hildur Hákonardóttir, Gunilla Lundahl, Ciara Phillips, Kristina Schultz, Nathalie Wuerth

Language English

Release date 2020/10.01

Font Times New Roman, Arial and Marker Felt