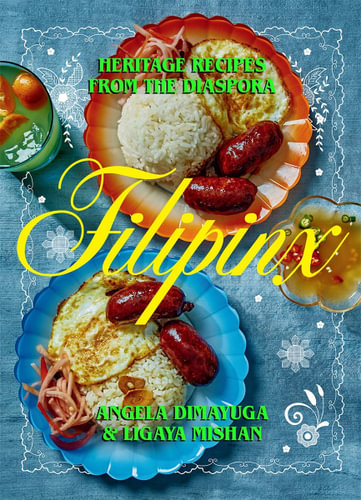

A footnote greets readers in the opening page of Filipinx, a new cookbook from chef Angela Dimayuga and The New York Times food columnist Ligaya Mishan. It reads: “The pattern here and throughout the book is inspired by piña cloth, which is made from the thorny leaves left over from harvested pineapples…It’s a testament to frugality and the insistence on wasting nothing, and a marker, too, of the colonial history of the Philippines…For Filipinos, embroidery became a way to take ownership of what they wore, to express their characters as individuals, and to make themselves seen and known.” This short statement highlights the ingenuity of the Filipino people. Piña cloth represents material innovation, design, and an anti-colonial identity and presents a sharp framework for understanding this deeply personal collection of recipes and stories.

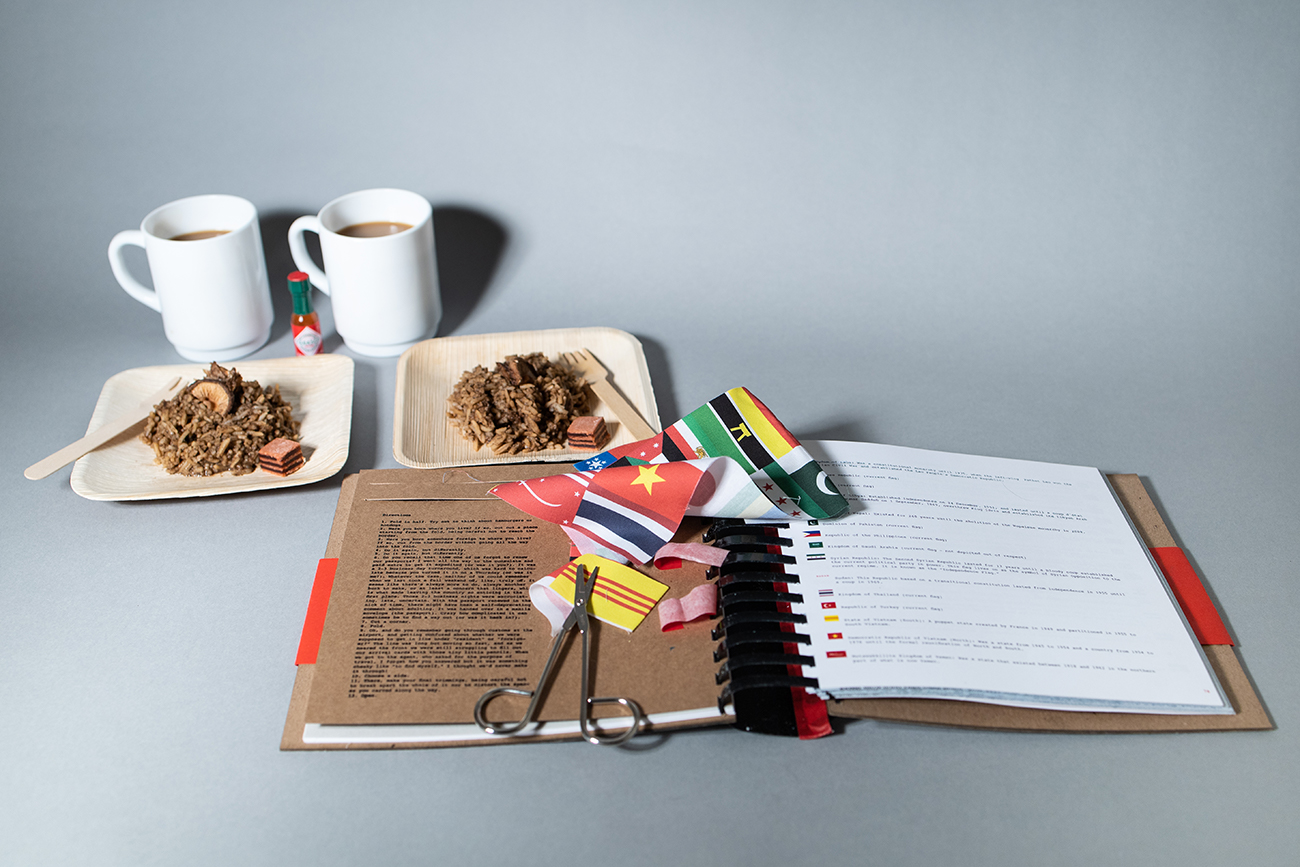

For many first generation Americans, food becomes a proxy for “home” — an imprecise place that is both geographically distant and suffuses the lived experience. For Dimayuga and Mishan, both children of the Filipino diaspora, the book becomes a vehicle for sharing stories that are at once personal—family photos and memories pepper each chapter of the book—and deeply universal. One of my favorite pieces from the book is an interview with the writer Jessica Hagedorn. In it, Mishan asks if Hagedorn’s 1990 novel Dogeaters was difficult to get published, to which she replies: “When publishers talk about the ‘universal,’ they usually have a very narrow idea of who their readership is…I think my job is to show that it’s no big whoop being Filipino. We are part of the world, not a trope or a catalyst.” The food of the Philippines also reflects this ethos—its flavors are rooted in the ingredients (banana leaf, coconut, cassava, ube) provided by the island archipelago and nurtured by a history of global entanglements.

Banana Ketchup is just one such example. The ubiquitous Filipino condiment is a radical innovation by “early 20th-century chemist and World War II hero, Maria Orosa,” the introduction to the recipe explains. Besides captaining the guerilla resistance to Japanese occupation, Orosa developed the banana-based ketchup in the face of a tomato scarcity during the war. Orosa’s lifelong dedication to championing ingredients from the island make her most enduring legacy a powerful representation of food as resistance.

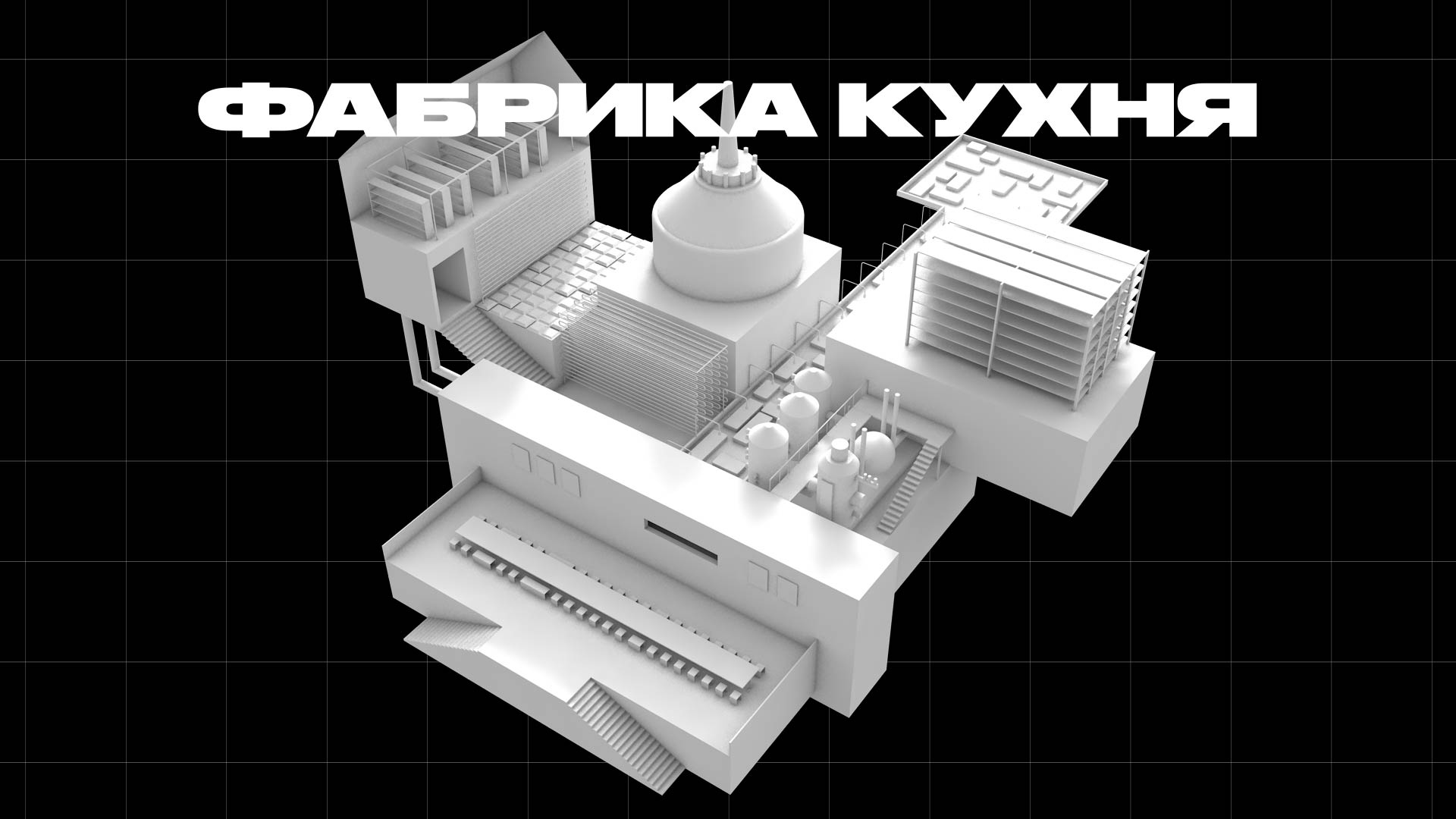

We wanted the design to be generous and abundant, a typographic pot-luck.”

Studio Ella

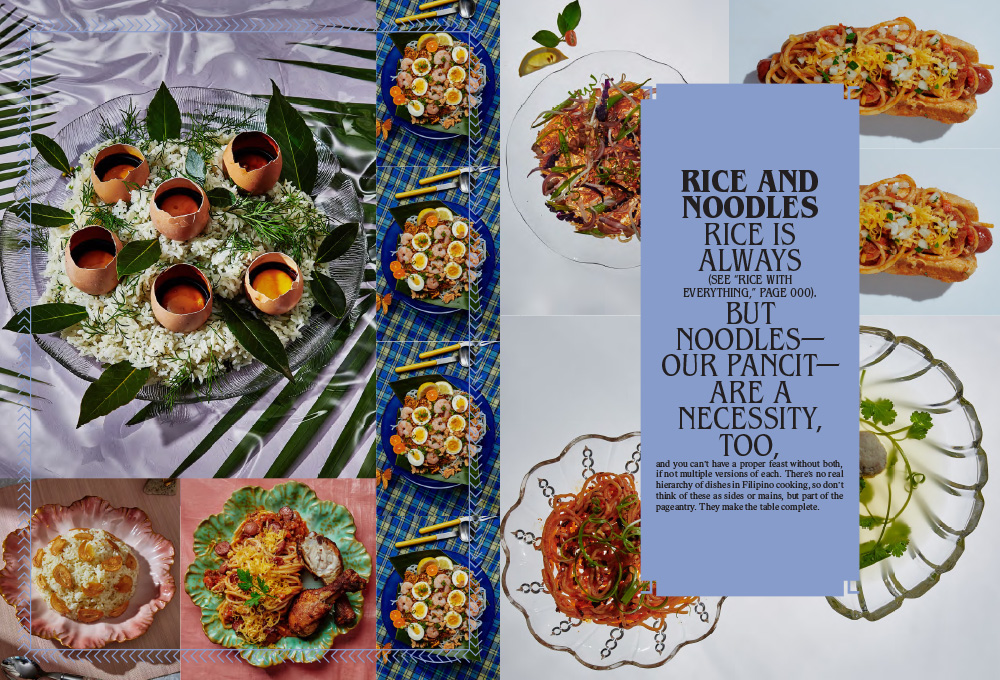

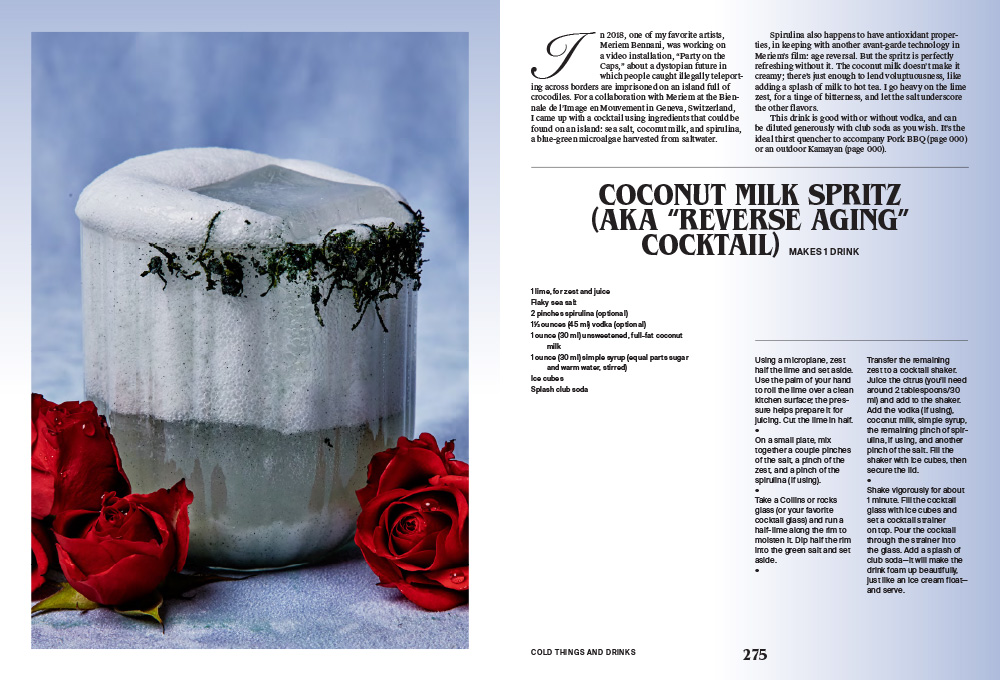

With 100 recipes ranging from the familiar flavors of adobo and lumpia to the highly involved chicken relleno recipe passed down to Dimayuga from her lola Josefina, the book pulsates with joy. The ultra-saturated photos by former Bon Appetit staffer Alex Lau seemingly float above the ombre fade of the recipe pages. The experience of paging through the book is anchored by the thoughtful design by the Los Angeles-based Studio Ella (helmed by Stephen Serrato and River Jukes-Hudson). “Angela came with a plethora of references—piña cloth, embroidery, tattoo symbology, plus the amazing photos she worked on with Alex Lau and Sue Li,” River and Stephen share. “They also documented a beautiful selection of food packaging. We loved the boldness, unexpected typeface combinations, and vivid color. The book design responds to these references, layering them together like halo-halo. We wanted the design to be generous and abundant, a typographic pot-luck.”

With the phonetic pronunciation accompanying each Tagalog recipe title, the book is an invitation to host a kamayan, a celebration feast that holds its own chapter in Filipinx, with your loved ones. As Dimayuga reminds us in her opening note, “Sometimes we didn’t need an excuse; we just celebrated our continuing, in this place far from what my elders once knew as home, in a country they had finally made their own.”