“Cooking is planetary, even cosmic.” And so the introduction to Black Almanac, a speculative website detailing an array of possibilities for reimagining planetary food systems over the course of the next three decades, begins.

Engaging with planetary-scale phenomena can be challenging. Between mass extinction, global warming, mass migration, and global pandemics the many complications of human-induced climate change are as frightening as they are unfathomable for many people. Yet the urgency with which people must find ways of coping and ideally mitigating the ongoing impact of these occurrences can hardly be overstated, and in order to think about and discuss these planet problems, finding channels of accessibility is required. For Andrea Provenzano, Philip Maughan and Nikolai Medvedenko’s project Black Almanac, that channel is food.

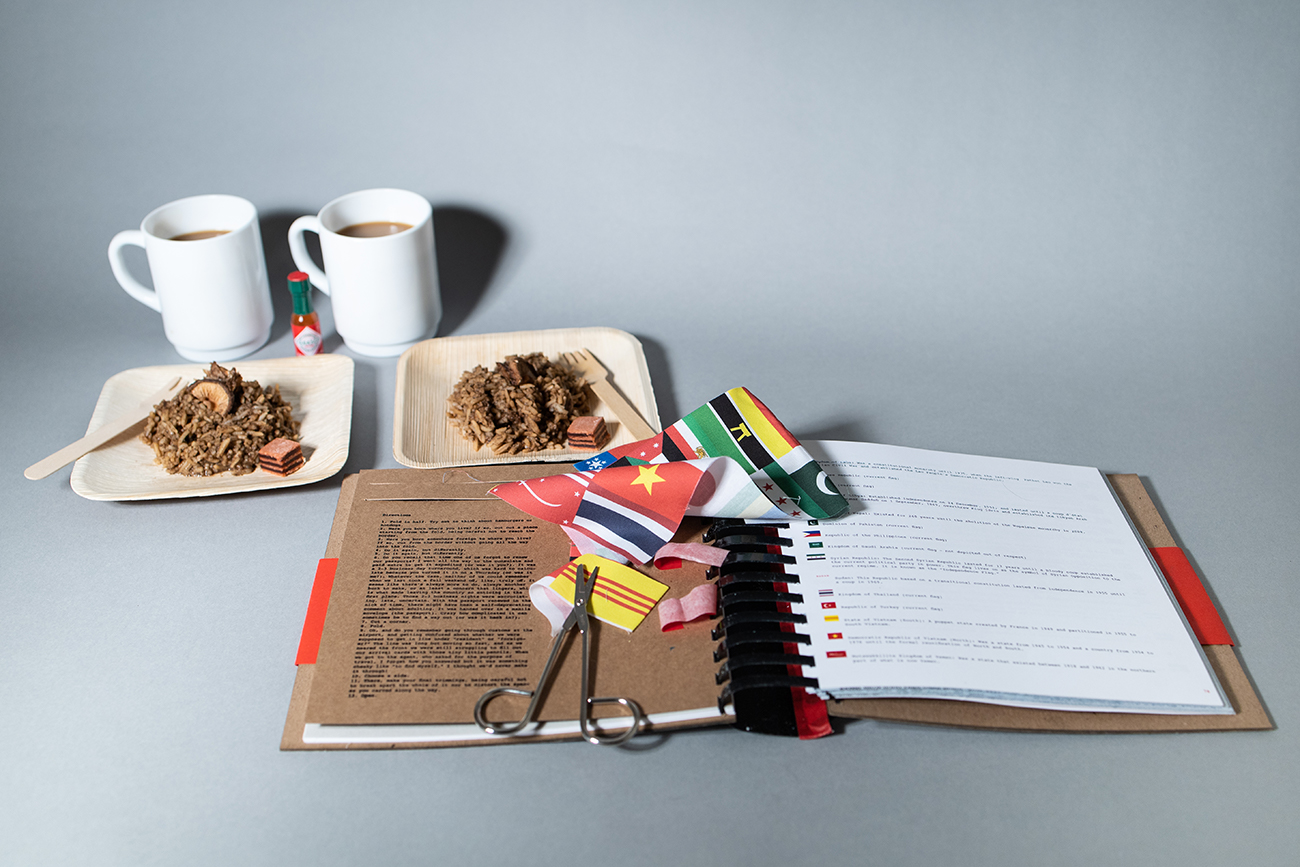

“I’d be able to talk to my dad about it and he wouldn’t just look at me blankly,” said writer Philip Maughan, one of the creators of Black Almanac. The Almanac is the product of five months of intensive research and design at Strelka Institute in Moscow as part of the institute’s three-year The Terraforming program that was, like most of the world, upended by global pandemic. Despite and perhaps because of the necessarily remote conditions of quarantine, the team behind Black Almanac created a novel interface for thinking about food—not merely as the material that we find on our plate everyday, but as a phenomenon that has and continues to change the Earth beneath our feet.

Manipulation of the Earth is exactly what Stelka’s The Terraforming program is about. The institute invites applicants from different disciplines for a 5-month intensive cycle to explore “urbanism at planetary scale, a venture that is full of risk—technical, philosophical, and ecological.” In the initial weeks of the program, participants were pushed to explore the possibilities of terraforming, the deliberate modification of a planetary body’s atmosphere, topography or ecology to make it more habitable for human life.

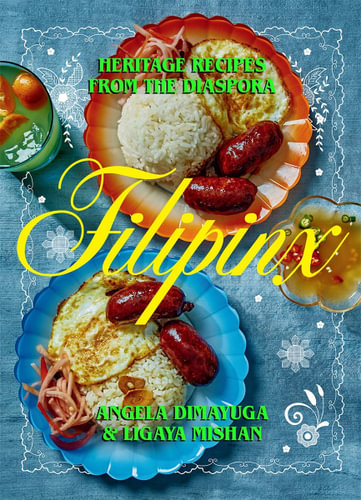

“I like to think about our project as a database,” explains photographer Andrea Provenzano, one of the creators of Black Almanac, “a database of the concepts that we all explored during the first weeks of The Terraforming.” Algae caviar, flavor engineering behind the taste known as “vanilla,” survey of contemporary farming infrastructure, a history of fertilizer, spirulina wastewater filtration, anatomical diagrams of “big food,” the nature of space food, and many more subjects are organized in a semi-chronological format in a scrolling catalogue of ideas on Black Almanac.

The almanac as an archetype is, “a technology that you can carry around. These are things that are really tied to human cultures as far back as Sumeria and probably beyond,” says Maughan noting that almanacs, for millenia, have been devices for thinking in accordance to the changes of the Earth. “It gives us a kind of calendar and allow us to think about pathways and deadlines—that are such a part of the climate conversation.” says Maughan. In this way, an almanac situates food not as something that is merely a packaged good—always the same color and shape, or an object frozen in an Instagram photo—but as something that has, is, and will continue to shift in the coming years.

While the three creators didn’t need any evidence to the fact of how quickly and dramatically food can change, the impact of the pandemic on industrial food production made it painfully obvious. “We were in the middle of a course about the need for large-scale planetary changes in response to Earth threats and things we know that are happening. Then it was happening in real time,” says Maughan. While the team of researchers had to forgo many planned research trips and working in the studio together, through remote working between Berlin and Moscow, they were able to persevere. “That affected the balance between research and production. I don’t think we would have been able to research as much as we did,” says Provenzano.

As the research found in Black Almanac reveals, food has so often been a matter of uncertainty. While subsidies for industrial food production and a recent cultural focus on the visual form of food can give the impression that food culture is static, and uneasily changed, but “even a cursory look at food history shows just how quickly food cultures emerge.” says Maughan. “I think that when the barriers, the economic barriers of subsidies are removed then amazing things can happen.” Between now and the year 2050, it is not a question of will food change for better or for worse, but how it will change and Black Almanac provides a medium for understanding what that might look like.