The choice, often deeply political, of a staple material/medium for an artist to work with can be both career-defining and a signature in her oeuvre. London-based Laura Wilson’s preoccupation for most of the last five years has been with dough—bread dough, to be exact—as a material to think through the politics of food, movement, embodied knowledge and a host of other themes. Her recent work Resting (2021), a new iteration of the dough performances she has been making across venues and projects since 2016, is too, an examination of the microbial lives that collaborate in the craft of bread making. Coming at (what is hopefully) the trailing end of the Covid-19 pandemic, this reflection on the role of microbes in food-making offers viewers of her work a segue into thinking about the ubiquitous nature of these microorganisms.

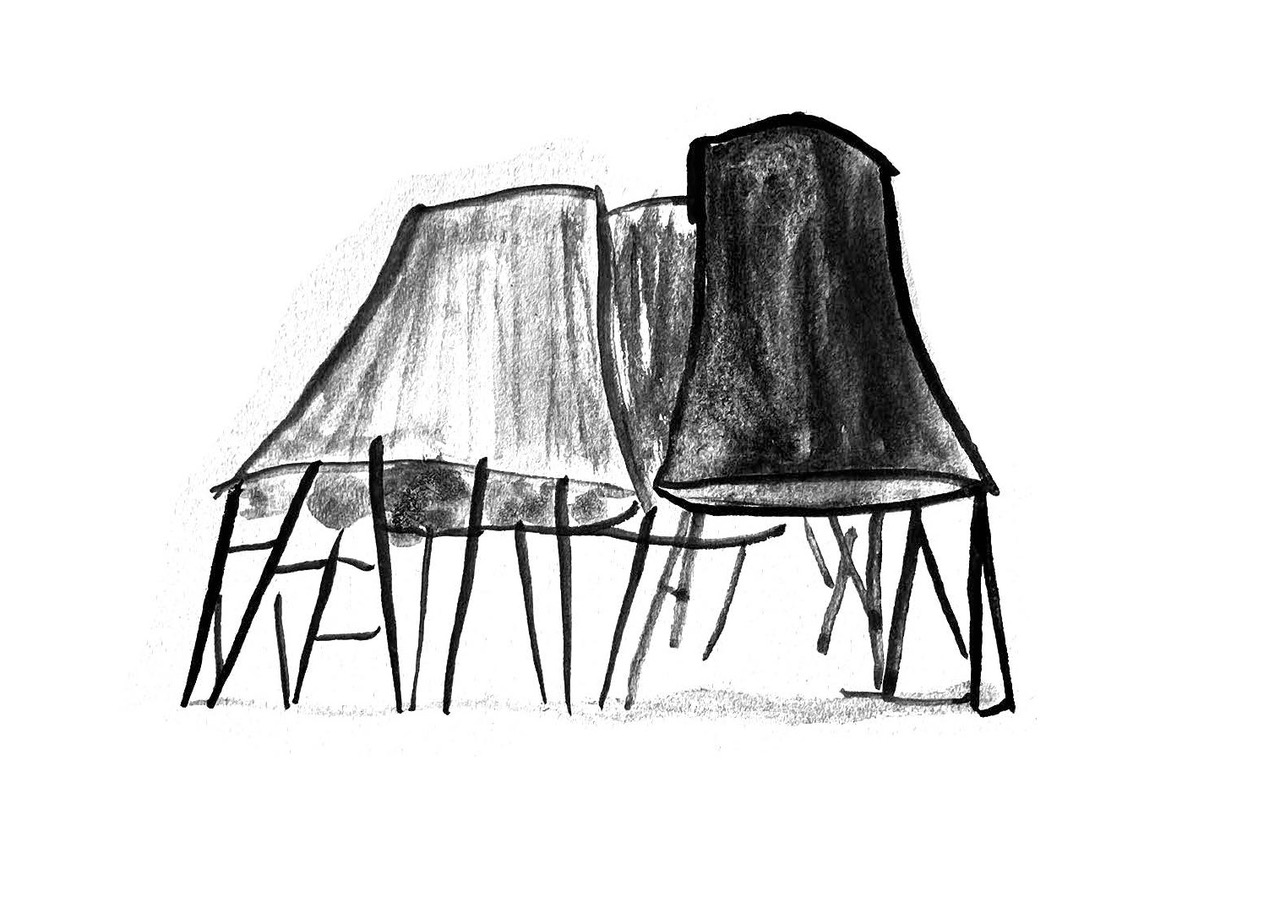

The performance of Resting activated Sofa-Bread, a piece of furniture designed by the London-based interdisciplinary design collective, The Decorators, for their Stanley Picker Fellowship project Portal Tables. Shown first during September’s London Design Festival at the Victoria and Albert Museum, with plans for a larger show at the Stanley Picker Gallery later in the year, Sofa-Bread, “is designed to provide moments of conviviality across humans and bacteria during the fermentation process involved in making bread.” The sofa includes two ceramic bowls for bread dough while inviting visitors to rest on the sofa, either with their feet up or down, sitting upright or lying down. While leaving bread dough to proof, or rest, is common terminology among bread bakers, Wilson told me over our video call, the dough is hardly ‘resting.’ That time is when the chemical reaction happens, she explains: “Things are happening all the time, but we can’t really see them.”

This interest in dough as a material for thinking about collaborations with microbes and the influence of terroir—the ways environment and geography influence taste—has led Wilson to look at various aspects of breadmaking, from the growing and harvesting of wheat, to threshing and milling flour, and the slow rigor involved in kneading the dough to bake a loaf. These investigations are realized in both Trained on Veda bread, an ongoing project that seeks to revive the popularity of the Irish malted bread throughout the United Kingdom, and through her dough performances where actors work with their bodies and the body of the dough: rolling it, stretching, folding; letting it and themselves change and move, emphasizing the physicality and the intimacy involved in bread baking.

Supposedly discovered by accident in the 1900s and popularized as a healthy, nutritious bread with a long shelf life in the UK until the 1950s, Veda bread is now sold only in Northern Ireland where Wilson was born. Her project, Trained on Veda (2016 – present), aims to connect bakeries and galleries through Veda bread. She worked with the baker Marc Darvell to develop a recipe for the malted loaves. Though the organic growth of the network of bakers and stockists slowed down during the pandemic, Wilson told me that her interest, apart from sharing the recipe, is in how recipes can shift and change from person to person based on their memories, cultures and embodied knowledge.

Her dough performances like Fold and Stretch (2016), Rolling (2017), You Would Almost Expect to Find it Warm (2018) and various iterations in-between stem from her interest in bread dough as a living material, “constantly responding to body heat, the air around it, it is absorbing the yeast from our skin, from its environment, but also the heat of the day or from who handles it [during performances]. So it can take on, in a way, a bit of a personality. Even your own mood can influence the dough,” she said.

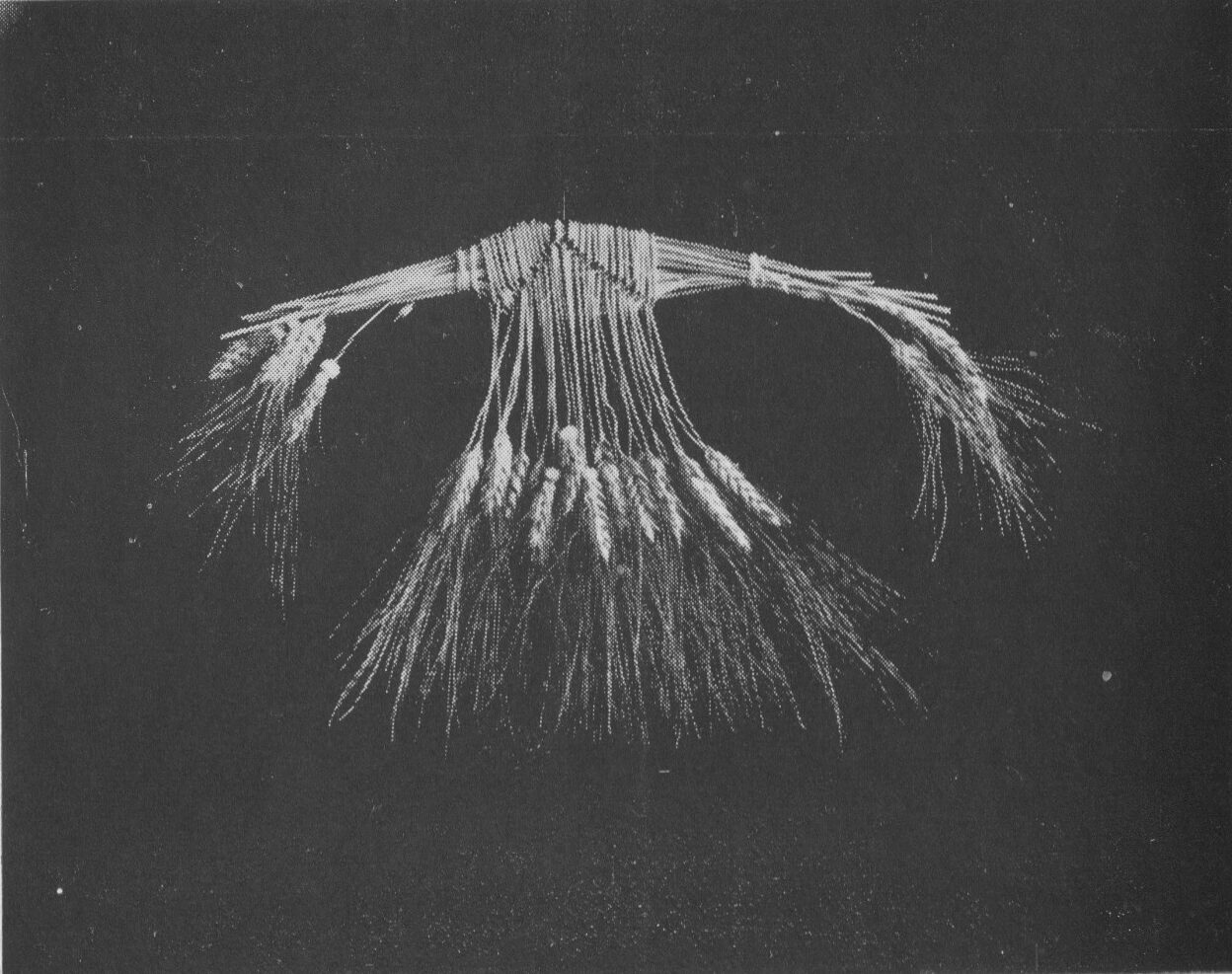

The actors in her performances thus move in tune with the other body mass of bread dough—the movements are meditative, slow, repetitive and adapted to each actor handling the dough. Elsewhere, Milling About (2017) reflects on the labor involved in milling wheat for flour, while a new site-specific work To the Wind’s Teeth (2021) / I Ddannedd y Gwynt (2021) uses choreography that mimics the learned movements required to thresh and winnow wheat to separate the grain from the chaff. The performance “investigates how the body learns, adapts, responds to and performs manual work, posing questions around labor, regaining lost skills, the link between food and well-being, and passing on knowledge through embodied practices.”

Breadmaking has always been a conversation in food politics, and perhaps more so during the pandemic when a lot more people leaned toward the craft and its associations with slow living, gut health, self-reliance and other such hashtags. With her videos and sculptural performances, Wilson’s works push such conversations further to ask questions and reflect on why and how we eat what we eat. Her interest is in having, “a broader conversation over bread and the politics of food, of course, but also our memories and recipes associated with that, conversations about food and where our ingredients come from.”