Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

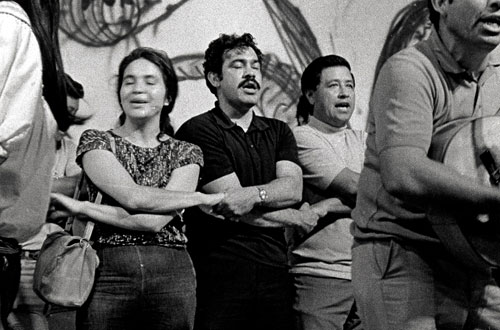

In an age where strikes and protests are largely publicized and strategic tactics and information are easily shared across social media, it can feel as though unions and activist groups for many causes are being given the airtime that they may not have received in the past to reach people. The efforts of The New Yorker Union this year averted a strike, finally reaching an agreement with publisher Conde Nast after almost three years of negotiations –– while Amazon workers are uniting for better warehouse working conditions, sparking backlash from the anti-union company.

Historically, unions and organizers have rounded up support through word of mouth and inexpensively printed and distributed flyers. Now, the click of a button or the tap of a touchscreen can send information to millions of people at once.

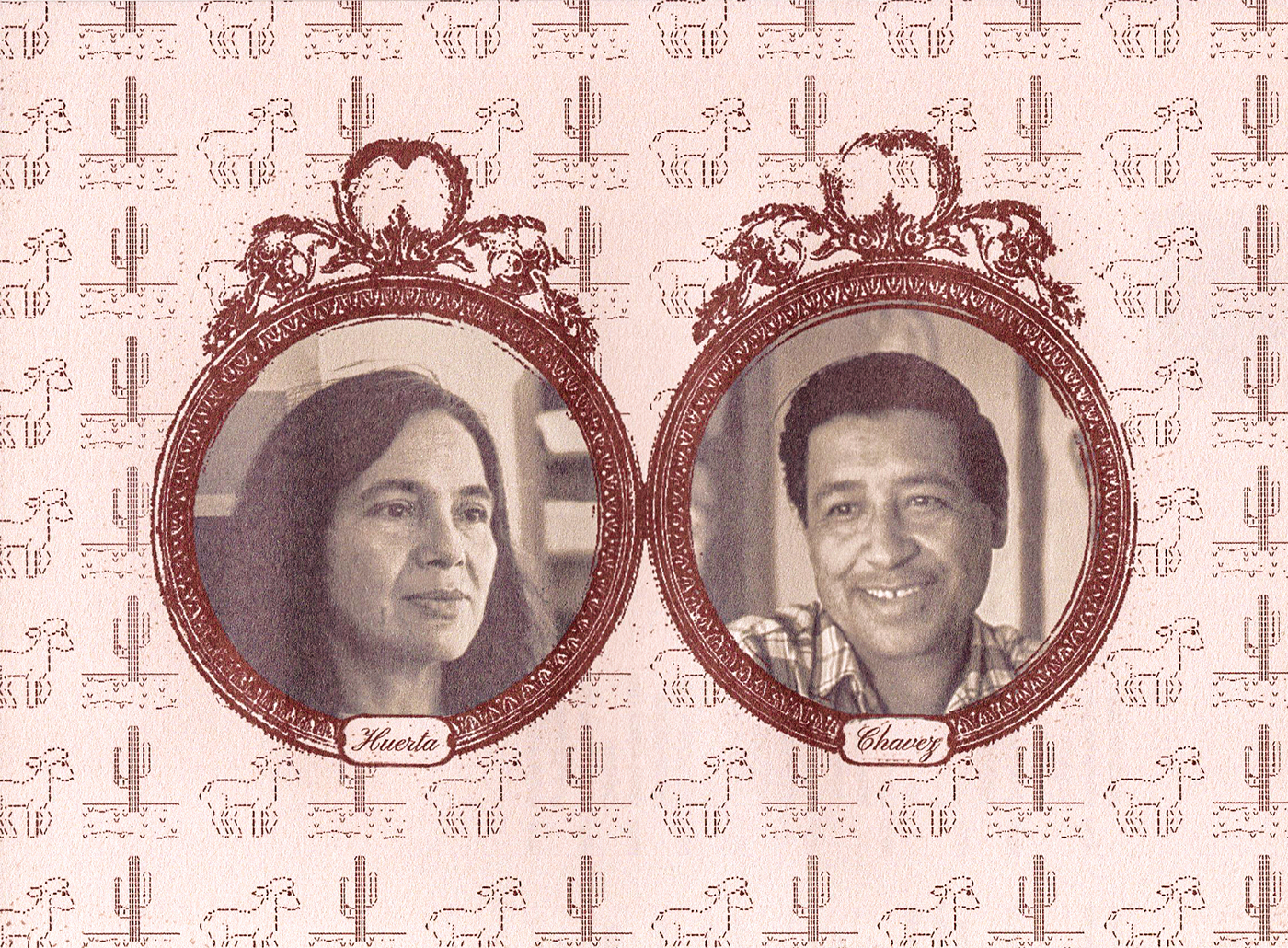

However, with recent news that the Supreme Court has ruled against protecting union organizers’ access to farms –– erasing an almost 50-year-old California law –– it is clear that the fight for the rights of underpaid and overworked farm laborers is ongoing. The law passed in 1975 following the work of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta’s union organizing efforts, was intended to “‘ensure peace in the agricultural fields between workers and growers” (The Washington Post).

Now, the Supreme Court has ruled that the law “unconstitutionally appropriates private land by allowing union workers to go on farm property to drum up union support” (NPR). NPR quotes Mario Martinez, general counsel for United Farm Workers, who points to the racism underpinning the exclusion of farm workers unionizing:

“You double down on that exclusion and discrimination by saying that a state law that’s been in existence for almost 50 years is not respectful of the growers’ rights…But there was no discussion of the workers who are essential workers to feed America. There was no discussion of their rights at all.”

At the same time over in Colorado, farmworker bills have just been signed into law by Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, providing state minimum wage, overtime pay and labor organizing rights, amongst other measures to improve immigrant rights (The Colorado Sun). The bill was lobbied for by Dolores Huerta herself, who worked closely with local farmworkers’ rights groups and Latino advocacy groups. Today, the organizing efforts of these unions are still just as important –– they encourage employees to share experiences, extend support, and apply pressure in the right places to destroy discriminative and unethical practices. So how did Chávez and Huerta organize and publicize the farmworker strikes that made American history and improved conditions for migrant workers, and how did they design a union with such a powerful identity?

Forming a Union

United Farm Workers of America, or UFW, was formed in 1966 by uniting the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) – led by Larry Itliong, a Filipino-American cannery and agricultural worker – and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), led by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta. The two unions, in joining forces, brought together communities of Filipino and Mexican migrant workers, in the fight for better wages, working conditions and workers’ rights.

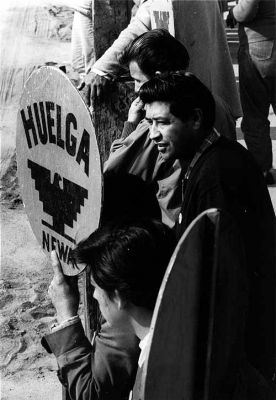

The predominantly Filipino farm workers of the AWOC had initiated a series of strikes against grape growers in Delano, California. Just a few days later they were joined in solidarity by a mainly Mexican-American union, the NFWA. Recognizing their strength in numbers and the struggles that both communities faced as migrant workers being denied the right to decent working conditions, it made sense to merge both unions, bringing about the birth of the United Farm Workers the next year.

In Chávez’s autobiography, César Chávez: Autobiography of La Causa (first published in 1975), he recalls organizing for the grape strike:

“We put out different leaflets every day going door to door in Delano, McFarland, Richgrove, Earlymart, parts of Wasco, Porterville, and Bakersfield…During that first week, the strike spread to about two thousand workers and some twenty farm labor camps.”

UC San Diego Library

Designing a Movement

The unions’ organizing power, distribution of information and close relationship to their communities helped the movement grow rapidly –– and visual design played a huge role in that. Each picket sign, banner and flyer was emblazoned with the union’s logo, bold type and sometimes humorous illustrations.

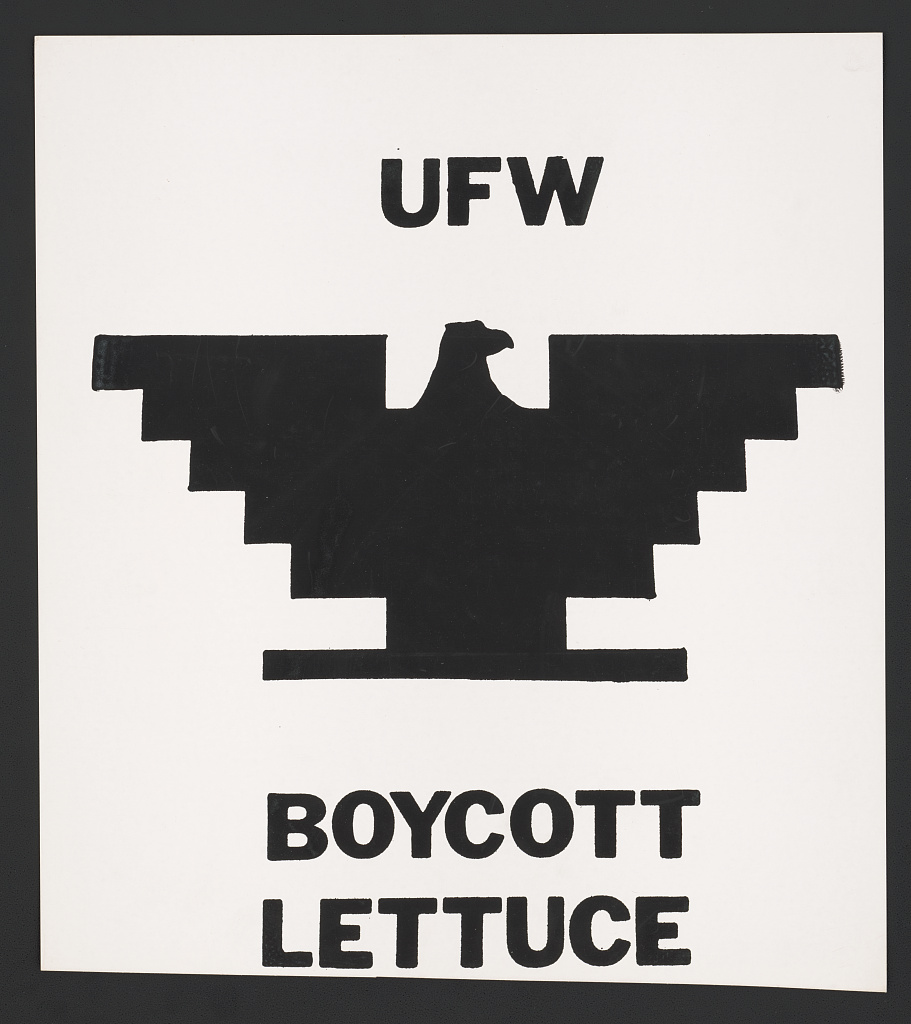

In describing the founding of the union, Chávez admits, “Dolores and I were the architects” –– the planners, authors and speakers. However, the union had several other leading figures, including Chávez’s family members. In 1962, Richard Chávez, César’s brother, designed the black eagle logo that became the iconic insignia of the NFWA and later the UFW, and a symbol for Chicano people. On the design of the union’s emblem, César writes:

“Many ideas were suggested, but we wanted something that the people could make themselves, and something that had some impact. We didn’t want a tractor or a crossed shovel and hoe or a guy with a hoe or pruning shears… It was Richard who suggested drawing an eagle with square lines, an eagle anyone could make, with five steps in the wings.”

The importance of the black eagle was replicability, accessibility and of course, communicating strength, with its angular forms and bold colour palette. Chavez chose the colors red, white and black, likening it to the “impact” of the Nazi flag –– also citingthe commercial logos of Texaco, Marlboro and Safeway.

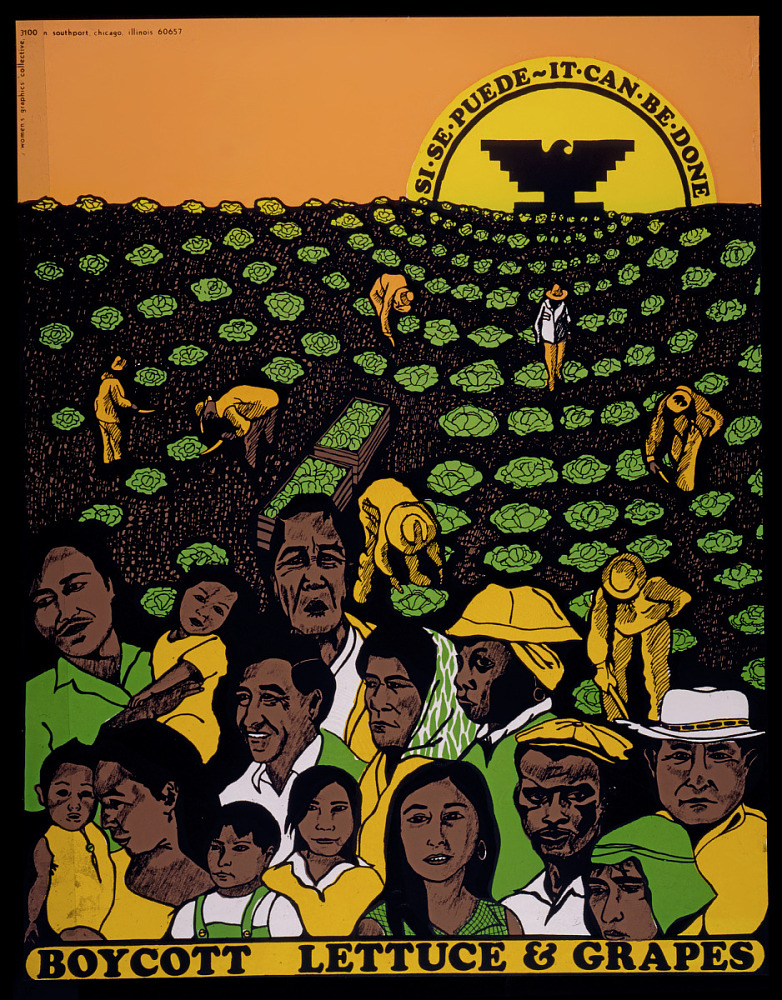

The Aztec style of the black eagle is seen throughout UFW material, which formed a key part of the Chicano art movement. The Chicano art movement created a space for Mexican-Americans to form a unique artistic identity in America — and the UFW’s design and distribution of posters, leaflets and symbols created a call to mobilize and politicize, using visual art as a tool for social change, equality and justice. Making ‘something out of nothing’ was the essence of the Chicano art movement — as Max Benavidez wrote for the Los Angeles Times just a few days after Chavez’s death in 1993,

“In the mid- to late-’60s, there were no grants, no art degrees; just a burning need for artists to say something about themselves and their situation. That’s what the work was about then.”

Printing for the People

The UFW even had its own “merchandising arm” and printing workshop known as El Taller Grafico, which allowed the movement to print protest materials in-house –– from silkscreen posters to picket signs, brochures to badges. It didn’t take long for the union’s activities to gain national media attention, and their archive of printed ephemera displays why.

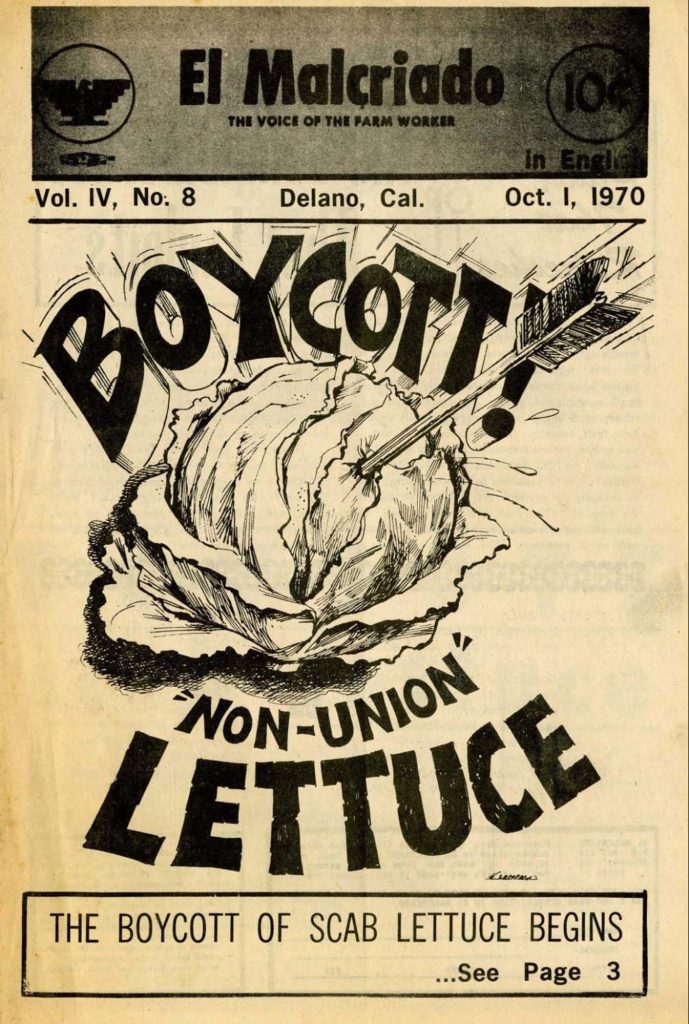

Below is the front cover of an issue of El Malcriado, an alternative newspaper that became the United Farm Workers’ official publication. The cover shows a detailed illustration of a lettuce to mark the start of the Lettuce Boycott of 1970. Inside are articles highlighting current and upcoming activities, members of note, and satirical cartoons. These illustrations were also turned into pin badges and stickers to be distributed to the public, encouraging them to boycott purchases of all lettuce that had not been picked by UFW members.

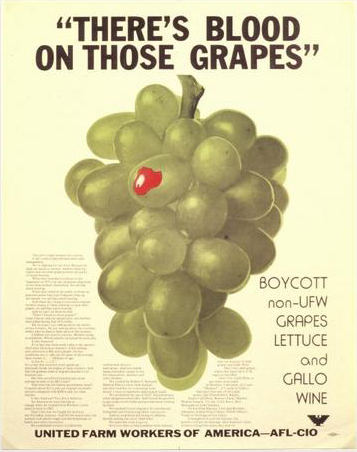

UFW printed ephemera, now recognized not only for its historical but also aesthetic influence, can now be bought for hundreds of dollars online, and online archives can be browsed of the posters, artwork and flyers distributed by members to communicate La Causa.

Fighting for the Future

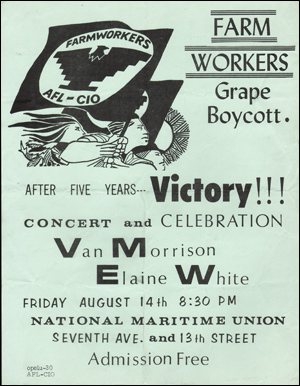

The United Farm Workers led a series of successful strikes campaigning for decent wages, healthcare and protection for exploited migrant workers. The Delano Grape Strike ended in victory after five long years in 1970, with the majority of grape growers signing UFW contracts to improve working conditions and wages. This was the result of the union’s pledge of non-violence and their dedication to communicating with workers and growers, through speech, performance and visual art and design.

Shortly afterwards began what became known as the Salad Bowl Strike, a series of strikes and boycotts in the Salinas Valley that led to the largest farmworker walkout in U.S. history. The campaign resulted in Cesar Chavez himself going on hunger strike, and later being arrested for picketing.The strike ended after seven months, but the UFW’s boycotts continued until the late ‘70s.

Today, United Farm Workers of America are still based in California, and live and work by the union’s original motto, “Si, se puede” –– “Yes, you can,” or “It can be done”. Currently the union is campaigning for a national heat regulation bill that would require the implementation of a “national heat stress standard”, to protect agricultural workers from the dangers of working in high summer temperatures.