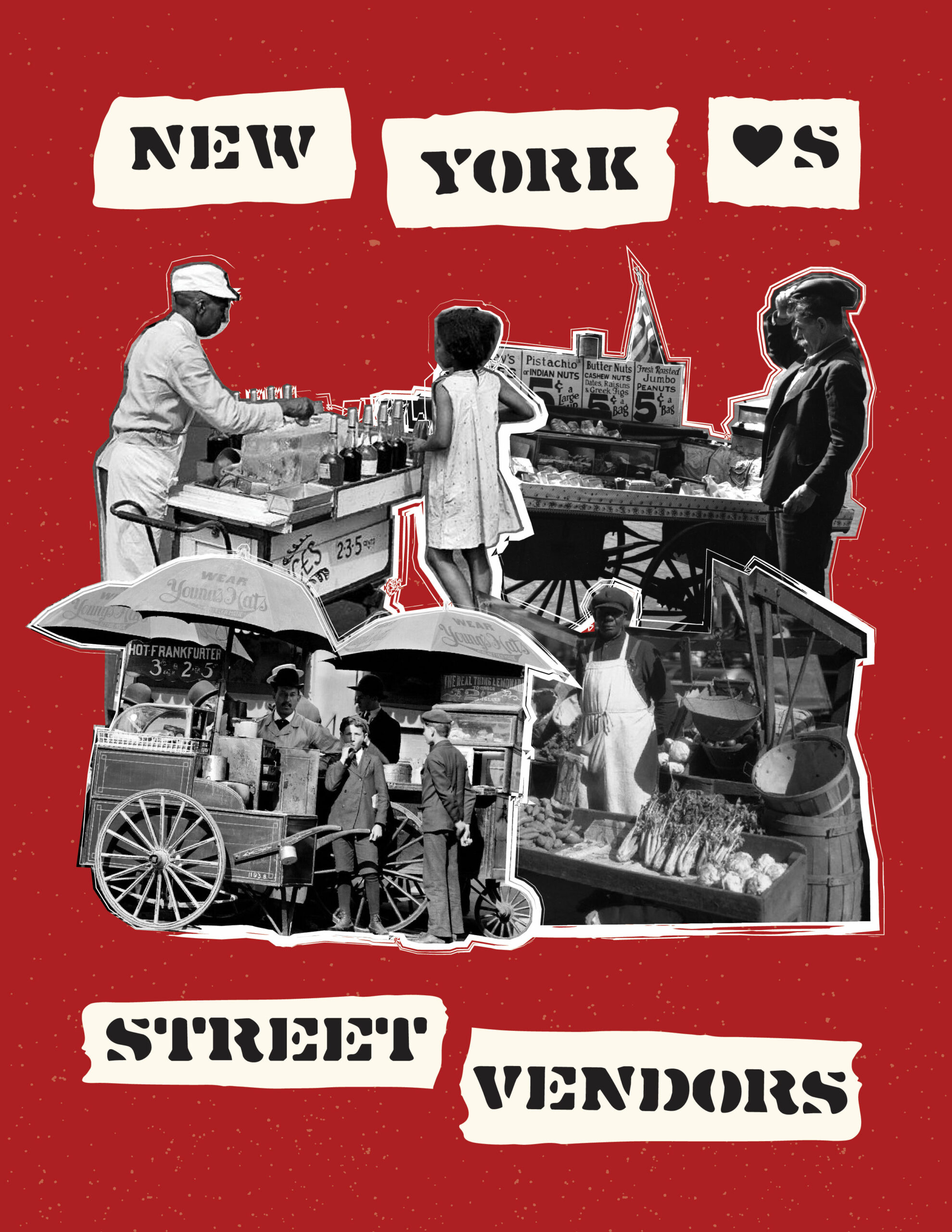

Walking throughout New York City — on sidewalks, outside of subway stations, and even down on train platforms— you are likely to find women, mostly from Latin America, standing behind shopping carts or wire laundry baskets, all selling fresh-cut fruit to commuters and hungry city dwellers alike. Their offerings often range from spears of sliced watermelon to perfectly cubed squares of mango with the additional option of condiments like hot sauce or chili flakes. A mainstay in contemporary New York landscapes, these women also represent a paradox at the intersection of policy, design, foodways, and livelihoods. The absurd reality is that in a city that is actively trying to increase access to healthy food, especially in low-income, Black and brown neighborhoods that have historically faced disparities in food access, through public education programs and policy interventions, immigrant women selling fresh fruit at affordable prices find themselves harassed, ticketed, and even criminalized.

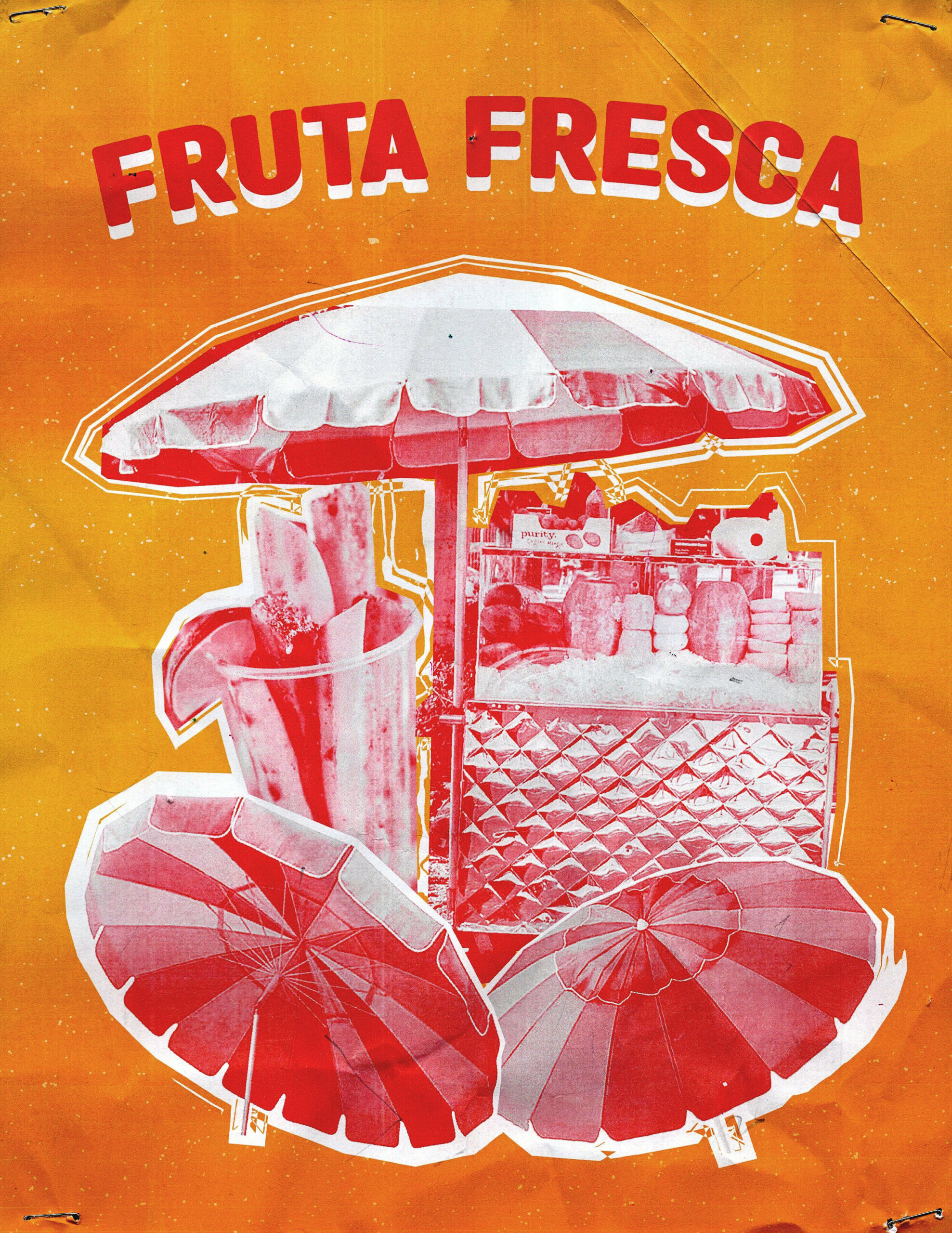

Selling fruit is a difficult business. The product spoils quickly and margins are thin. This is one reason bodegas and small groceries in low-income areas sell a limited selection of fresh fruit, if they sell it at all. But fruit vendors have managed to solve many of the practical, business, and design problems inherent to the practice. Though an informal cut fruit cart may look ad-hoc and haphazard, nearly every element is carefully designed to serve a purpose. Vendors use wire laundry carts or shopping carts because they are lightweight and inexpensive. The laundry carts also fold up and are easily transported between home and their vending spot. Carts are mobile, meaning vendors are free to move around a neighborhood to follow the daily rhythms of crowds. Vendors cut fruit at home, packing them in ready-to-go plastic containers, often kept cool with ice. The display of colorful cut fruit in clear containers, which sit on a tray atop the wire basket, is an important part of a vendor’s on-site marketing. As any vendor will tell you, customers have to be able to see the product. Their fruit can be an impulse buy, something picked up on the run. Appealing to customers’ senses, visually and aurally through cries of frutas! mangos! sandía! is all part of making the sale.

Working in and through informality recognizes the innovation and ingenuity of people making a living on the margins.

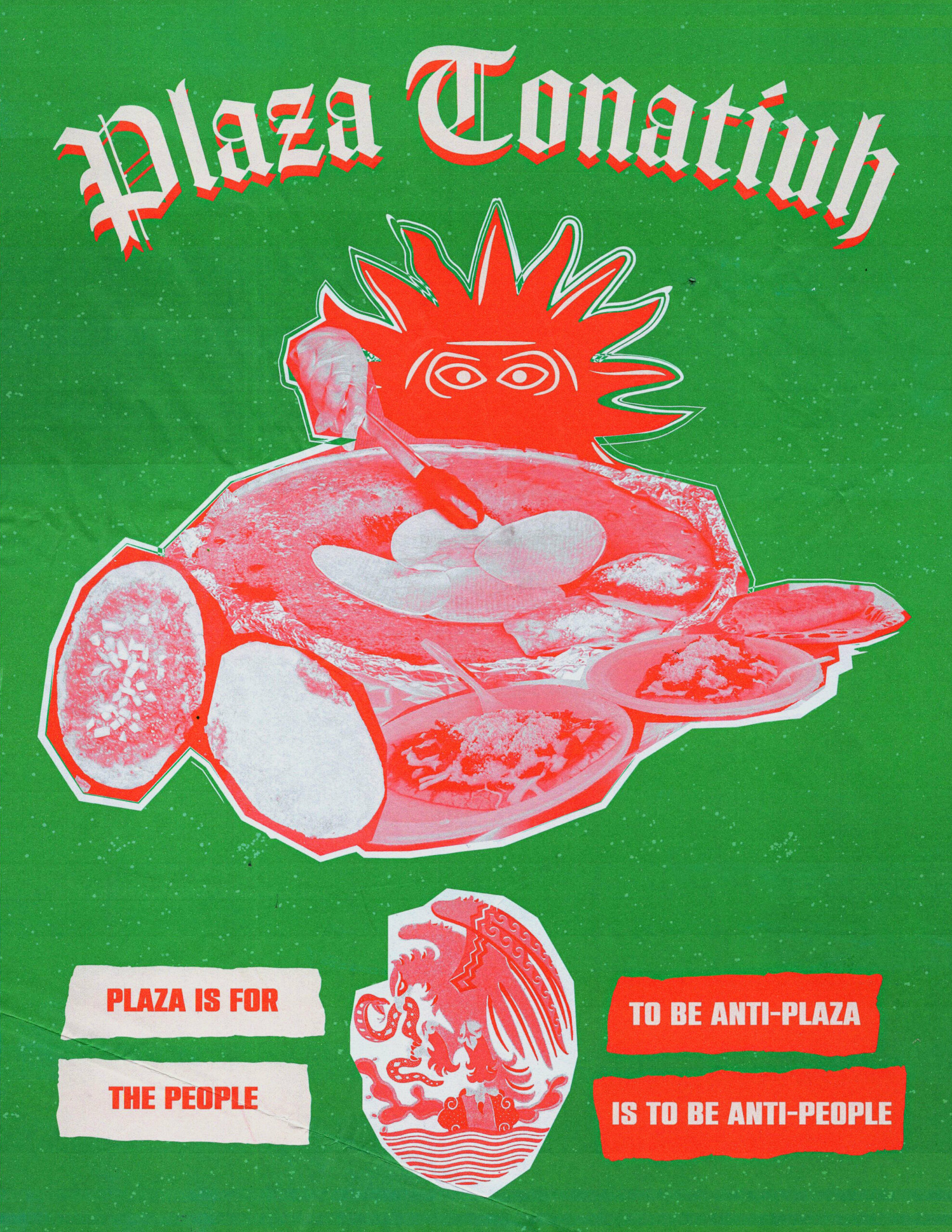

But none of this is technically legal. Most vendors of cut fruit do not have food vending permits. Until 2021, street vendor permits had been capped at 3,000—a number that had remained unchanged since 1983. A new law passed in 2021 lifted the cap, adding 4,000 new permits over ten years. But even with access to permits, cut fruit vendors face tremendous barriers to legalizing their businesses. In order to conform to New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) food vending regulations, fruit vendors would have to switch their wire carts out for stainless steel vending units. Not only would these units need to have hot and cold running water if the vendors were to cut fruit at the cart, but the goods would then also have to be stored within the unit, not displayed. Alternatively, if vendors cut fruit off-site, it would have to happen in a restaurant-grade cooking facility, rather than their homes. This would mean that the fruit could not be stored at home,but rather require storage at a commissary, where vendors would have to rent space. Just following one of these requirements would make it extremely difficult for vendors to make a profit, much less survive as a business. Taken together, DOHMH regulations make the entire proposition of selling cut fruit legally at affordable prices a non-starter.

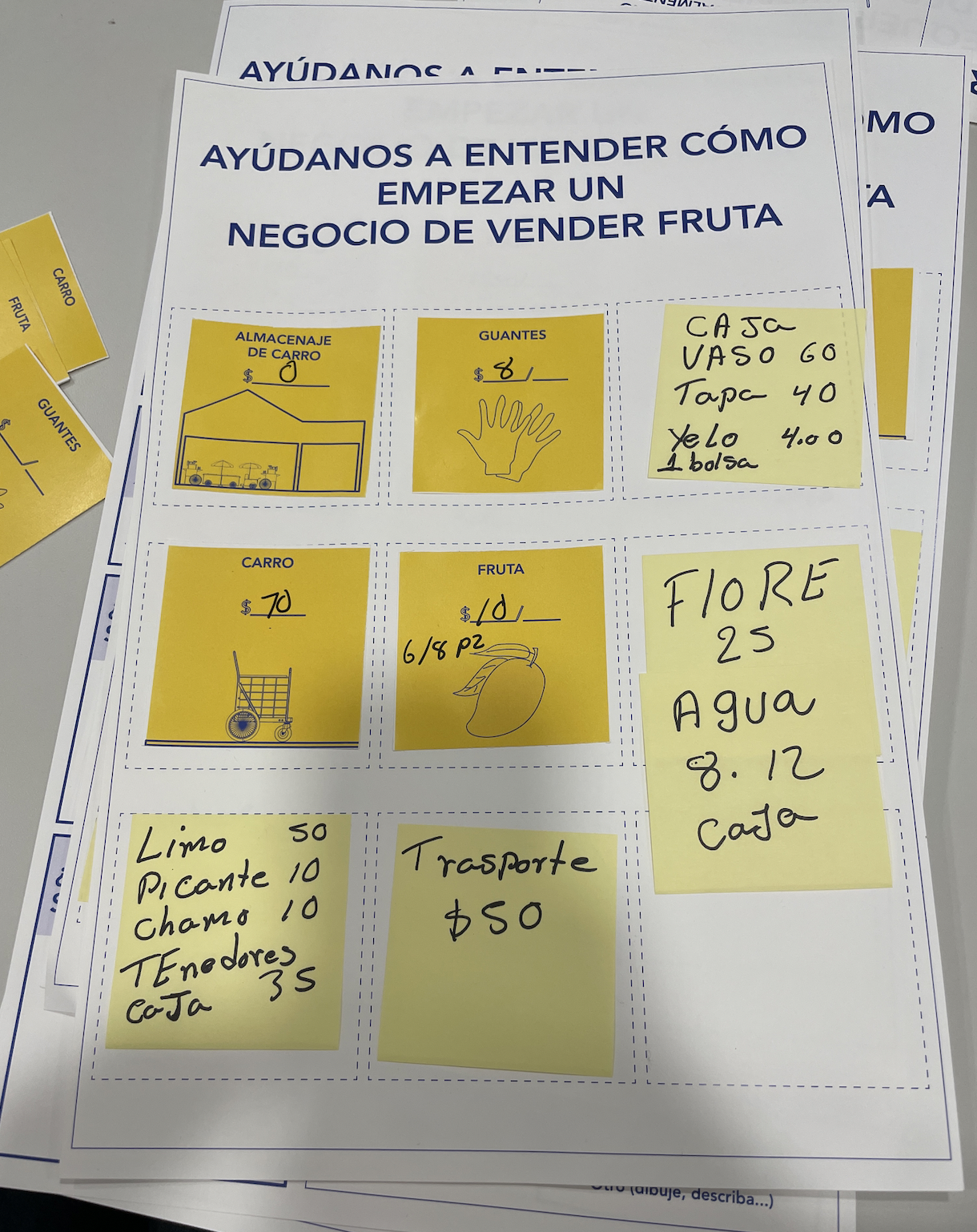

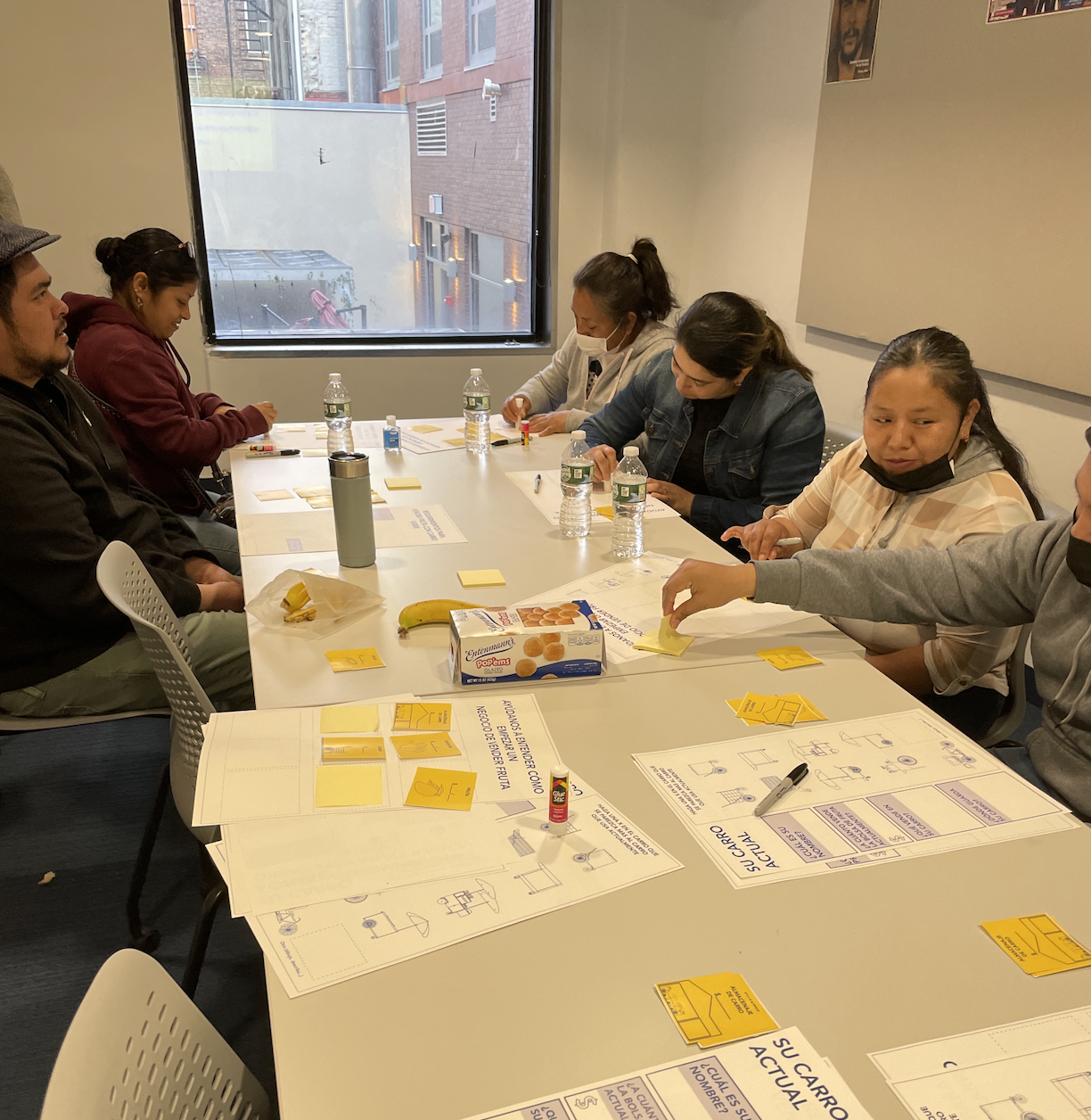

In the spring of 2022, I, along with architect Ane Gonzales Lara, worked on a project, funded by the Pratt Center for Community Development that sought to create an affordable prototype for selling fruit that met basic DOHMH requirements. This work was done in collaboration with fruit vendors and in conversation with officials at DOHMH. Two collaborative design sessions with vendors allowed the team to learn how vendors met logistical and design challenges through their own innovations. We also started a dialogue with vendors, making suggestions around materials, components, and other upgrades which would potentially allow carts to be approved by DOHMH. After a few iterations, initial prototypes were developed using input from vendors. These simple prototypes used the basic shell of the wire carts already employed by vendors, and added basins made of non-porous material to serve as spaces for the storage of fruit in ice as well as for meltwater. The prototypes were then shared with DOHMH officials. But as work proceeded, we began to realize that we were working across two vastly different design systems: the informal problem solving of vendors and the formal standards and compliance-based system of DOHMH. The priorities of the DOHMH, of risk mitigation through predictability, standardization, and overdesign simply did not translate to the lived realities of vendors. Nearly any conversation about design possibilities ended with the city’s lack of flexibility on elements like stainless steel, hot and cold running water, and requirements to prep the cut fruit in a commercial kitchen.

Even with only modest upgrades, the new designs were still costing nearly $1,000 and would have to be stored in rented space in commissaries. Given these new costs, many vendors balked. As one women said during a design meeting about a prototype, “Pago esto o pago mi rente.” (I pay for this or pay my rent). Ultimately, while the project did not produce a workable prototype, it was a valuable learning experience and helped identify specific rules that are based on principles of overdesign which serve as structural barriers to legal livelihoods for New York’s most vulnerable citizens.

If the city is concerned with social justice, access to healthy food and access to livelihoods, rules must emerge from the realities that currently exist.

The informal workforce in New York is only growing, with many recent migrants turning to street vending to make ends meet. If the city is concerned with social justice, access to healthy food and access to livelihoods, rules must emerge from the realities that currently exist. These design and policy principles are common in the Global South, evident in programs like incremental upgrading of informal settlements. Working in and through informality recognizes the innovation and ingenuity of people making a living on the margins. It posits that those like the women selling healthy snacks of cut fresh fruit to hungry New Yorkers are innovators that should be part of a design and policy conversation; that they should be listened to and worked with, rather than simply being punished for their own conditions of need.