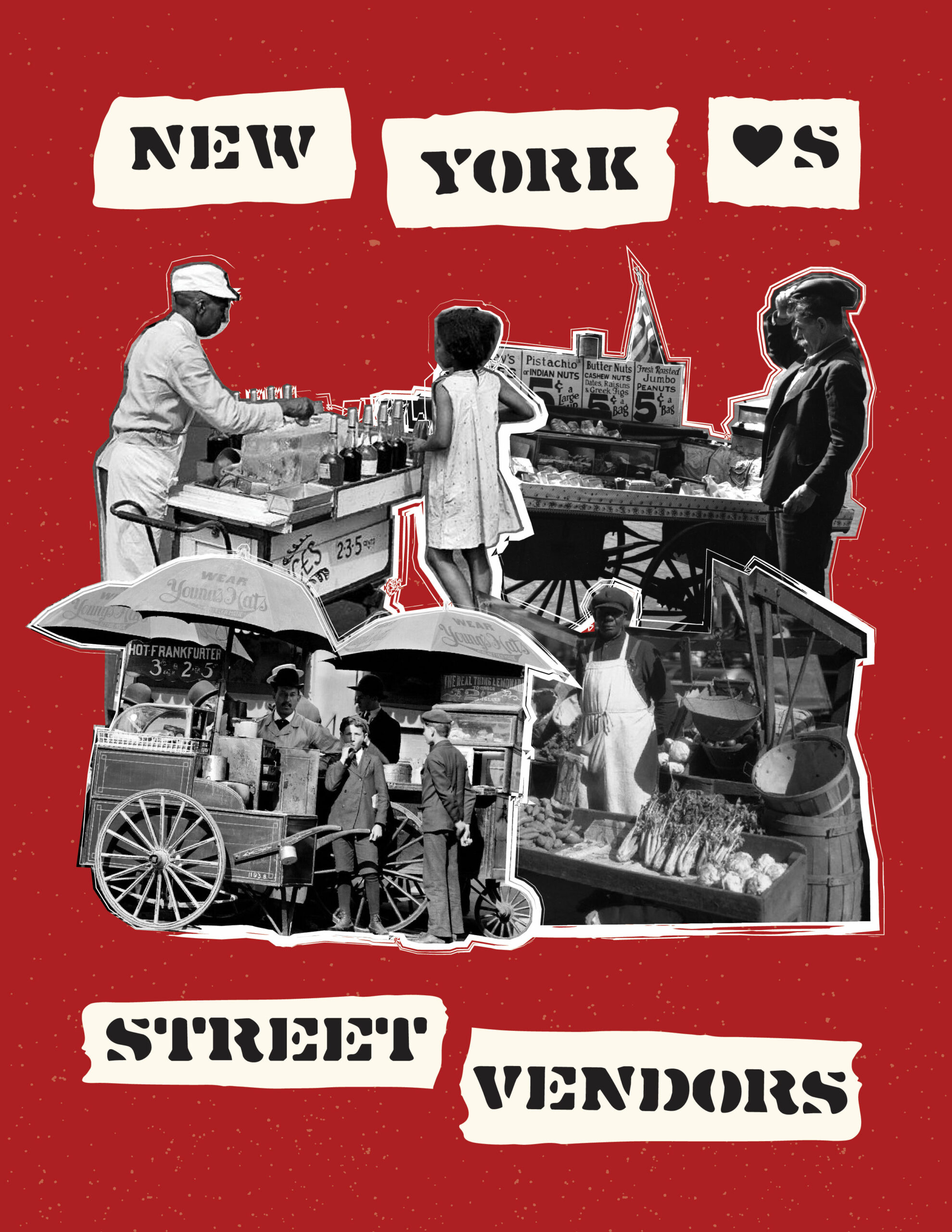

Who is the city really for? In this month’s editorial series from MOLD, we return to the streets of our publication’s hometown, New York City, to ask this question. In a dining landscape that is known for extravagance and hype, many New Yorkers will tell you that some of the city’s best food—from sizzling tripa mishqui to perfectly crispy dosas—is actually found in the street carts and stalls that line the city’s busiest avenues. However, for the past year Mayor Eric Adams has spearheaded a city-wide crackdown on street vendors, an extension of a wider ramp-up in policing across the city’s public spaces that has resulted in the targeting of the city’s immigrant and Black and brown populations. As a result, we have seen the suffocation of previously vibrant community gathering spaces and economic hubs such as Jackson Heights’ Corona Plaza or Sunset Park, rich cultural and economic ecosystems that expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic when many turned to street vending to make ends meet. In the pieces we’ll be publishing across the next few weeks, we highlight the voices of organizers, vendors, economists, and planners on the future of vending, the role of public space in the fight to preserve New York’s essential informal economies and what it looks like to build a more equitable food system.

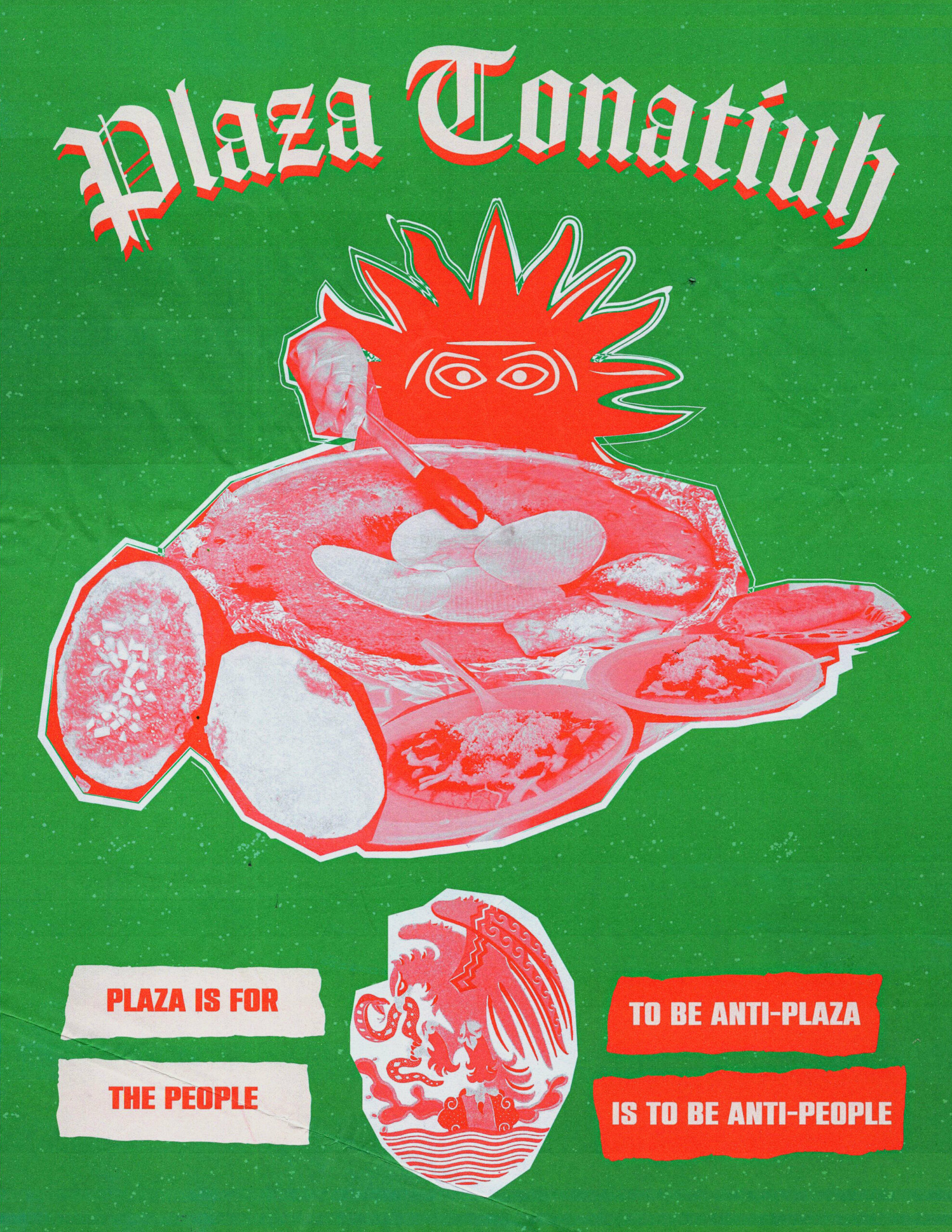

Earlier this fall, the MOLD team paid a visit to Sunset Park, where the activist group Mexicanos Unidos hosts Plaza Tonatiuh, a bustling Sunday market for street vendors to gather and hawk their wares, eat, and dance in the Brooklyn neighborhood. Up until this spring, the market was located in the neighborhood’s namesake public park, before police and parks enforcement officers moved to shut down the market, forcing them to take up residence in a private lot on the outskirts of the neighborhood. We kick off the series with a podcast with community organizer Brian “Leo” Garita as well as the Plaza’s street vendors speaking on the current landscape of vending in New York as well as what it means to build solidarity among street vendors as a workforce. We also have a conversation with series contributor Ryan Devlin, who studies street vending and design solutions for vendors.

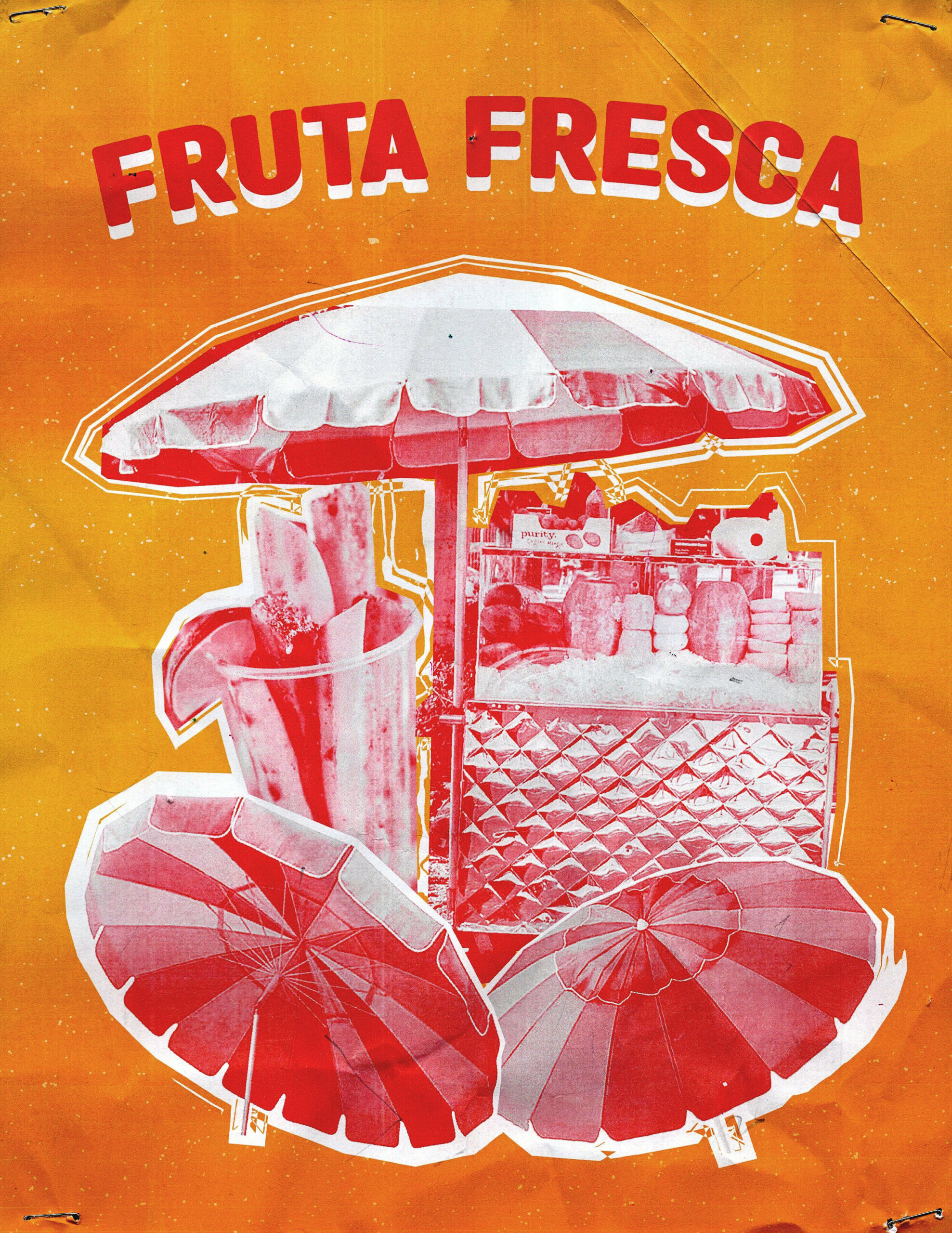

In Ryan’s piece, the urban planning scholar examines the spatial, political and design barriers that New York’s street vendors face every day through the lens of the street carts, which so many of New York’s fresh-cut fruit vendors use, as a design object. Economist and researcher Debipriya Chatterjee rounds out the series with a piece recounting the impact that vendors have had across the city’s history in shaping the New York we know today. She delves into what steps must be taken from a policy standpoint, outlining a path forward in order to build a more viable and safe future for street vendors across the city.

In our meditations around food and our celebration of the flavors, textures, and dishes that shape and excite our palates, we recognize that food does not exist in a vacuum, but is rather the product of interconnected systems of labor and capital. Through this exploration of how many New Yorkers live and eat in the city, we hope to hone in on the relationships of interdependence that true nourishment often demands. For us at MOLD, interdependency has remained present in our minds during this period of immense worldwide grief. By peering into the sutures of that which binds us together, particularly with our most vulnerable neighbors and comrades, we search for new ways of turning toward one another.

With gratitude,

Isabel