MOLD’s series of Food and Abolition considers how the political, social and economic project of prison abolition, ending the prison industrial complex (PIC) and setting in place reparative networks of care, can inform our movement for redesigning sovereign food systems.

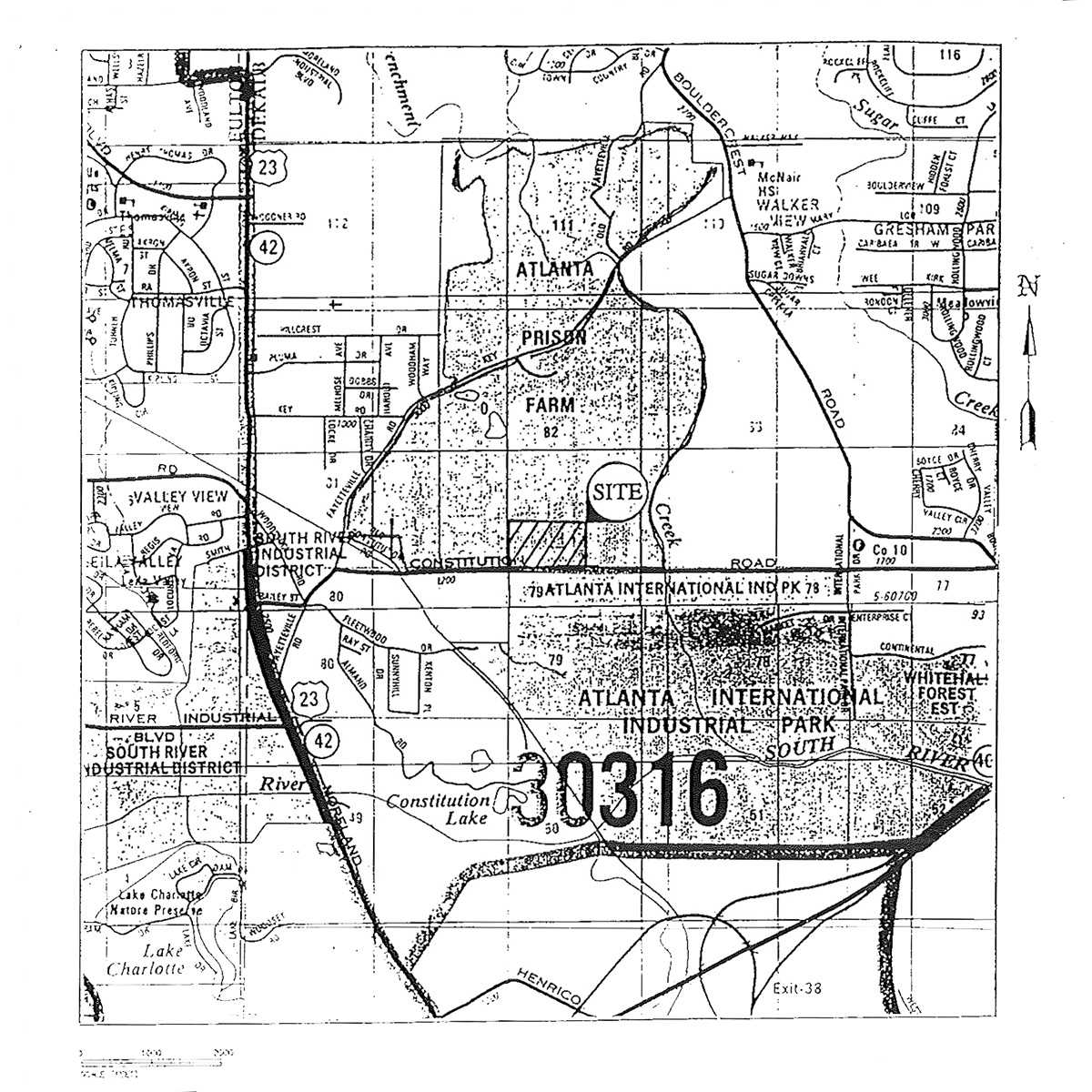

In an incomplete history of the Atlanta Prison Farm written in 1999, city planner Jillian Wootten asks, “Who has future plans for the property and what will it become?” The answer to the second question — what will it become— has taken on increased urgency as activists continue what is now a three-year long fight to stop the construction of a proposed $90 million police training facility in the city, more commonly known as “Cop City”. Nestled within the Weelaunee Forest—the largest greenspace in Atlanta, the proposed facility would become one of the largest police training sites in the country, located on the same site that formerly housed the Atlanta Prison Farm. This prompts a third question: do we continue the carceral legacy imposed on this land or do we do what abolitionists call for and reimagine it completely?

After the Civil War, Southern States addressed cash flow and infrastructure problems by following a well-worn playbook: subjugate earth and [Black] people in pursuit of capital and progress. As incarceration expanded rapidly and exponentially, physical prison infrastructures were soon exceeded. One solution for this was the convict leasing system. In Georgia, the prisoners were leased to private companies, which generated income for the state. From road construction to agricultural work on plantations, prisoners’ labor was an essential contribution to economic recovery and helped build the “new South” of the Reconstruction era.

From plantation to prison farm, the land that could become “Cop City” has been conscripted in the work of domination for centuries

By the turn of the twentieth century, however, the convict leasing system was losing public confidence. Some workers complained that the system undermined their ability to find fair-wage labor and public dissent grew after investigations into mistreatment of prisoners. Georgia abolished its convict leasing system in 1908, with other states soon following as well. The abolition of the convict leasing system did not end practices of uncompensated farm labor, however, it merely transformed them. Georgia and other states began running their own prison farms, meaning the state purchased land to be developed as income-generating enterprises. Under the guise of self-sufficiency and humanitarianism, historian Talitha LeFlueria makes it clear that these prison farms were “structured as a for-profit carceral entity.”1

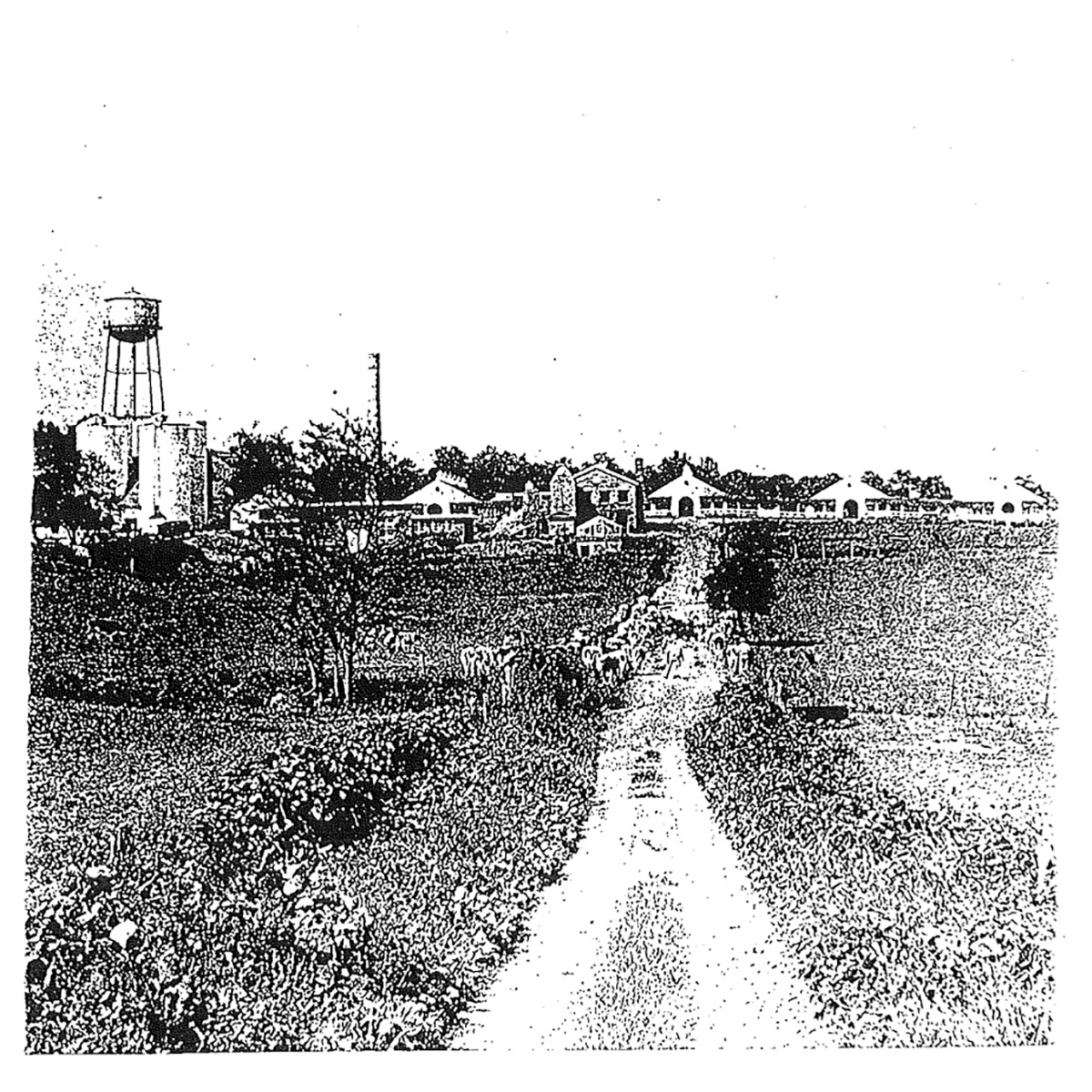

It was at this historical moment that the Atlanta Prison Farm entered the scene. Instead of being leased out as labor to private entities, prisoners farmed agricultural lands owned by the prison system itself. The plantation-turned-prison-farm operated from about 1920 to 1990 producing a range of crops that included corn, greens, and tomatoes. According to Wootten’s report, it also included dairy production facilities and a slaughterhouse for processing pork. Like the convict leasing system that preceded it, the Atlanta Prison Farm became an essential part of the prison system’s economic infrastructure. In addition to providing upwards of six thousand meals a day for prisoners across the system, the farm also generated a profit. By 1959 the prison farm had expanded to produce nearly 900 tons of food, which netted a $115,000 profit for the Georgia prison system.

- 1. LeFlouria, Talitha L., 2015. Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South. Durham: UNC Press, 141.

The Atlanta Prison Farm reflected a model of infrastructure building that was deeply anti-Black. Despite claims that prisoners on this farm were treated humanely—or at least more humanely than those at the federal penitentiary located about eight miles away—the practice of uncompensated state-building through farming was rooted and perfected in chattel slavery.2 From plantation to prison farm, the land that could become “Cop City” has been conscripted in the work of domination for centuries.

Given these histories of agriculture being intimately tied to unfreedom, the work of food justice is necessarily tied to the aspirations of abolitionists who propose not only the abolition of prisons but also a total reimagining of society. The proposed training center reinscribes that plot of earth in the Weelaunee Forest with the same carceral practices. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Those defending the forest and speaking out to #StopCopCity hold deeply to a belief that where harm and violence once thrive, healing and abundance can take its place.

Prior to the #StopCopCity movement itself, Black-led and multicultural organizations were already engaged in campaigns and actions to defund or abolish the police. After the murder of Rayshawn Brooks by APD officer Garrett Rolfe less than three weeks after the murder of George Floyd, protestors marched to the Wendy’s where Brooks was killed. Since the location for the proposed training city was announced in 2021, Atlanta-based activists and environmentalists have worked to halt construction plans. Some of these activists, known as the forest defenders, began to occupy the forest. In January 2023, the movement gained national and international attention and support when forest defender Manuel Esteban Paez Terán (also known as Tortuguita) was shot and killed by Atlanta police who claimed he fired first. Since then, large-scale rallies, bail funds, signature campaigns, and thousands of public testimonies have taken place. During a march on Nov 13, 2023, police deployed tear gas and flash-bang grenades to stop protestors from reaching the proposed site—despite the fact that the protestors’ plans were to plant 100 tree saplings. Where they sought to plant life, APD sowed violence and harm.

- 2. Atlanta City Prison Farm, Atlanta Community Press Collective.

Activists have been showing us every day that land that has been used for prison agriculture and confinement can be reimagined for food justice and liberation

The lands we inhabit—with fractured histories and debts owed—tell stories about “pasts” we do not want to repeat. The proposed training center poses a threat to land and body. But it also provides a lens through which to understand the intertwined histories of land, policing, and agriculture. Where some see the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, the rest of us see a “past” that created a foundation for over-policing and the devaluation of agricultural practices; a past where subjugation of land and body for profit was rendered acceptable because of ideologies that say some amongst us are less than human. Where some see safety, many of the rest of us see terror; a terror that is not only dangerous to those in its immediate surroundings but also to the world itself. And where some see inevitability, the rest of us see possibility.

In April 2023, the Weelaunee Coalition—a network of educators, parents, and children—posted a video showing their engagement efforts to Stop Cop City, which included planting gardens under the banner “Weelaunee People’s Garden.” In March, activists hosted the Food Autonomy Festival at the proposed site. Over the course of three days, attendees planted over 200 trees, took nature walks, and imagined other uses for the forest land, which is an important part of the Atlanta ecosystem. A different way of relating to land and each other is possible. Activists have been showing us every day that land that has been used for prison agriculture and confinement can be reimagined for food justice and liberation.

When I ask myself what (food) futures I want to see, that vision includes food forests, farms and farmers that thrive from feeding their communities, liberated lands that are stewarded by communities and not corporations, and workers being fairly compensated. All of that and more is possible when we thoughtfully reimagine places that were or could be used for punishment and imprisonment. Activists on the ground in Atlanta know this. I hope the rest of us can see it too.

- 1. LeFlouria, Talitha L., 2015. Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South. Durham: UNC Press, 141.

- 2. Atlanta City Prison Farm, Atlanta Community Press Collective.