Sustainability. A few terms may come to mind when reading the word. Climate crisis, environmental action and eco-friendly for example. A professor of mine once shared a slightly different take some years ago: “If someone asks you how your relationship, partnership or marriage is going, if it is a healthy one, you wouldn’t say ‘yeah it’s great, it’s super sustainable’…” There is something about this example which emphasises sustainability as the ‘just about good enough’ option. For the sake of understanding the impact of language and how it shapes our cultural values, behaviours and design approaches, it is worth analysing the definition of the word sustainability and to rethink our dependency on it in order to nourish a healthier world.

According to our most relied upon search engine, in the broadest sense sustainability refers to the ability of something to maintain itself or continue over a long period of time. Sustainability is also often broken down into three pillars of development: environmental, economic and social. Zooming out further, ‘sustainability’ appeared for the first time in the Oxford English Dictionary during the second half of the 20th century. By contrast, the equivalent terms in French (durabilite´ and durable), German (Nachhaltigkeit, literally meaning ‘lastingness’) and Dutch (duurzaamheid) have been used for centuries. Whilst many people attribute the rise in eco-consciousness and use of the word sustainability to the environmental movement of the 1970s, the demand for raw materials and an awareness of their impact on the environment has been a consistent concern throughout human history.

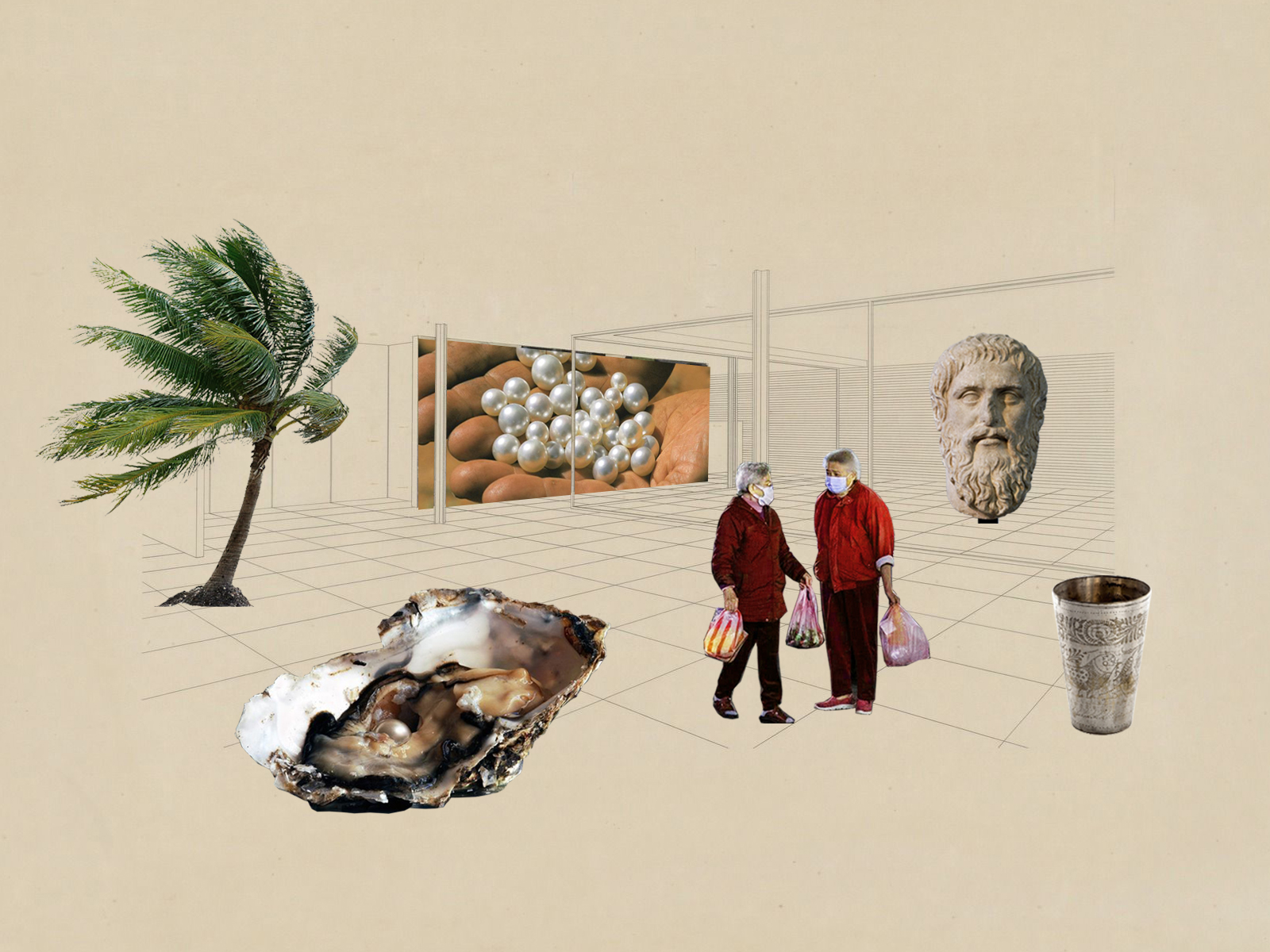

The roots of sustainability can be traced back as early as the ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek and Roman civilizations, when there was awareness of environmental issues related to deforestation and loss of soil fertility. Plato in the 5th century BC and Pliny the Elder in the 1st century AD for example, discussed different types of environmental degradation resulting from human activities such as farming, logging and mining. They were not only aware of environmental damage, but also recommended what we would call sustainable practices to maintain the ‘everlasting youth’ of the earth.

Fast forward to 2022, sustainable development continues to be a highly used term and compromise between growth and conservation. However, one could argue that genuine sustainability and genuine development from a puristic point of view, are irreconcilable.

Beyond the oxymoron element of the term ‘sustainable development’, the word ‘sustainability’ can also have negative connotations when considering its desirability or accessibility. For example, some sustainable, organic and responsibly sourced products are unaffordable for multiple communities. To be in a position of choosing whether or not to buy sustainable products in the first place, depending on cultural contexts and demographics, can be a privilege. For others, making the ‘sustainable choice’ comes with pressure or being guilt tripped into doing something they should do over something they want to do. Moreover, in our convenience culture, many people are not willing to sacrifice ease and affordability for sustainability’s sake, as highlighted in this COP26 study sharing Glaswegians’ attitudes towards sustainable consumption. This study identified a gap between what people say they would be open to do for the planet versus what they actually do and why.

Even the sustainability of the term sustainable is in question according to cartoonist and satirist Randall Munroe. In his web comic Munroe predicts that the word ‘sustainable’ will be used on average once per sentence by 2061. The humour (or reckoning) in this cartoon highlights how frequently we use the ‘S word’, and how our reliability on it far surpasses our understanding or implementation of it.

This comic provokes us to reevaluate our dependence on the word sustainability. Some suggested alternatives that may strike a stronger chord than the S word include environmentally prosperous, environmentally respectful, bio-contributing, eco-abundant, climate relevant and so on… I hope you can think of more.

Dr Franzisca Weder, Senior Lecturer at the University of Queensland in Brisbane Australia, specialises in the areas of sustainability communication and corporate social responsibility. In her co-authored paper on ‘(Re)Storying Sustainability’, Weder explains there is no one meaning to the word sustainability:

“Sustainability means to reflect on the interrelationship between natural and social systems on various dimensions of space and time. This reflection is always connected with evaluations, it is “spiced up”with morality and value based decision-making processes and implies a variety of meanings of sustainability.”

Value based decision making processes is the phrase I would like to focus on. The consideration I am about to share does not diminish the powerful efforts in the realm of human centred design to research incentives for sustainable environmental prosperity through behavioural change. It is part of a fundamental journey that all design education and practices should embrace to care for our planet. Instead, I would like to highlight a distinct starting point that doesn’t have to do with explicit sustainability environmental prosperity at all. Or change for that matter.

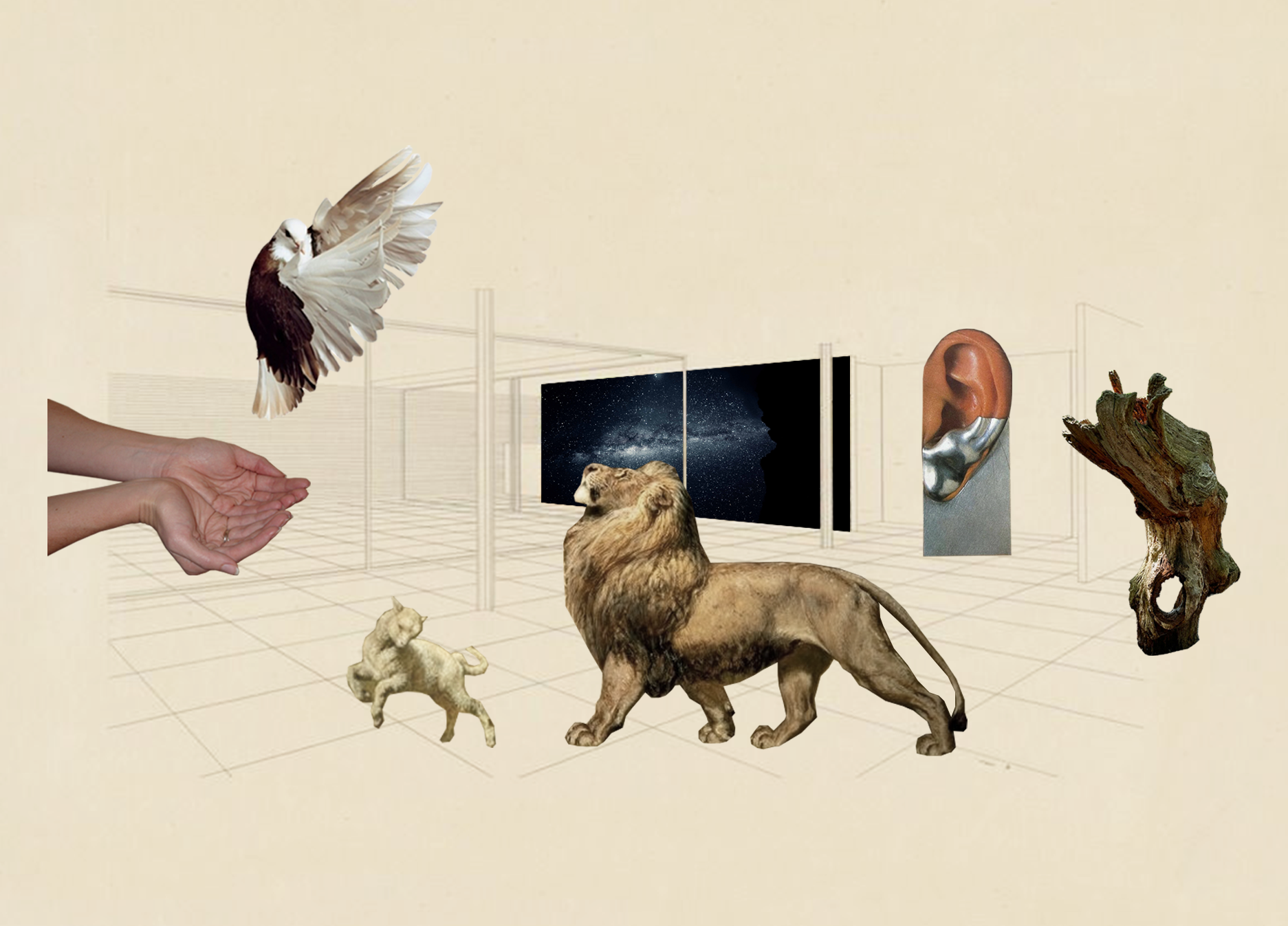

The idea is for designers and creators who want to cultivate greater environmental behaviour, to not focus on behavioural change but on behavioural consistency. There is enormous opportunity in understanding how human creatures across different cultures have behaved, currently behave and what they continue to value, before pushing for behavioural change that is overtly linked to the S word (and all the potential aforementioned connotations it comes with, such as sacrifice, inconvenience and expense).

In other words, what can we learn from consistent human behaviour that is not explicitly about ‘sustainability’ but is related to environmentally beneficial outcomes?

From behavioural change for sustainability, to rituals and habit creation that integrate environmental action.

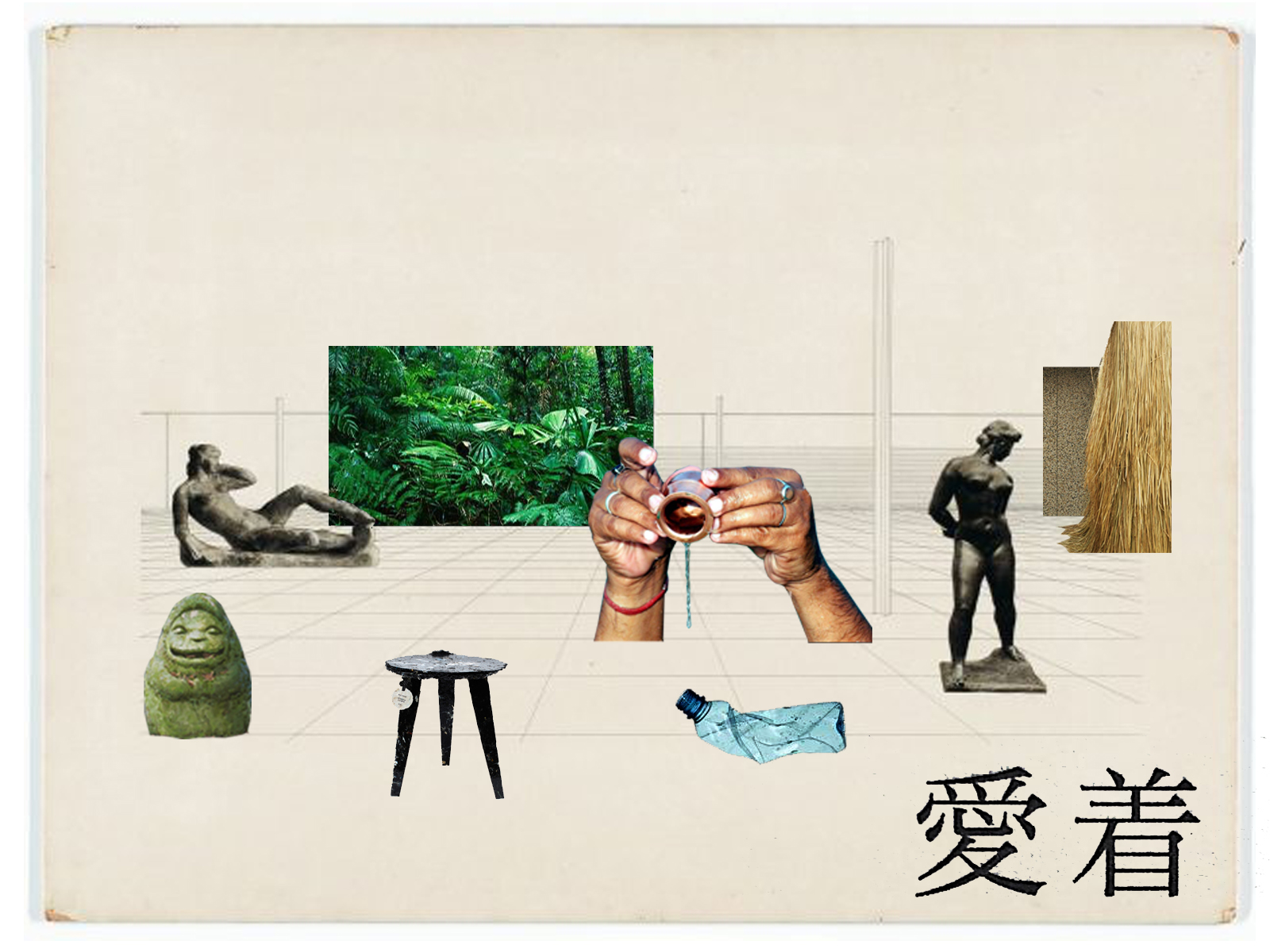

Take for instance, the waste management system in Taiwan. Residents are legally required to hand-deliver their trash to the trucks, which has transformed a polluted island into a clean and largely litter-free society. A tax on producing garbage combined with fines for littering, have incentivised people to throw out less and significantly reduce waste. The magical takeaway however, has to do with the social element. As the canary yellow garbage trucks play a jingle version of Beethoven’s Für Elise, residents gather to catch up with each other as they wait to hand deliver their trash bags and recyclable items. Taking out the trash becomes a social event for the old and the young alike, akin to small block parties. What can be regarded as a menial task in many cultures has become in some sense a ritual in Taiwan. This isn’t insignificant, considering how much waste is produced in cities like New York where there often aren’t any trash cans at all and residents rely on disposing their trash bags on sidewalks for collection. For those of us who have been lucky enough to visit or live in the city that never sleeps, the negative effects of that kind of waste disposal are clear. Alternatively in Taiwan the act of taking out the trash has become associated with a social gathering, providing a moment of community connection, resulting in less litter and waste. If our Taiwanese community has sparked any curiosity for further reading, this co-authored 2015 paper on habitual behaviours and climate relevant actions, published between The University of Exeter, University College London and University of Bath, dives deeper into the link between ‘habitual behavioural patterns’ and environmentally consequential activities.

Julia Watson, designer, activist, academic and author of Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism, describes Lo-TEK as a movement to rebuild an understanding of local knowledge to ‘generate sustainable, prosperous and climate resilient infrastructures.’ In her recent talk with SPACE10, Julia Watson states ‘the most effective technologies are those that are actually embedded in our communities.’ In light of learnings from the Taiwanese waste management system, I would extend this logic beyond technologies and further to community rituals or cultural values.

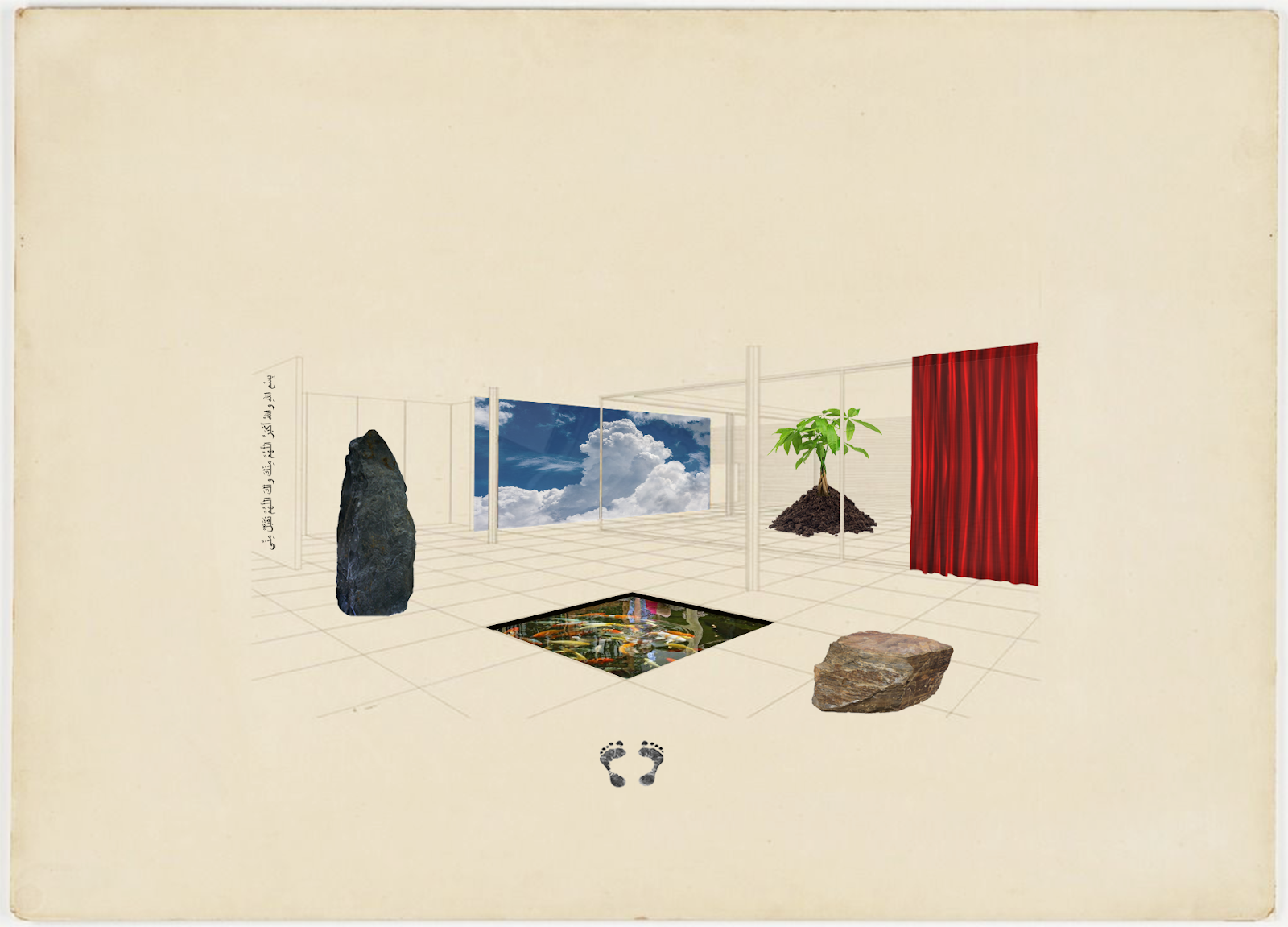

Take for example the subtle if not profound value based decision making processes made in India and Japan, both tangible and cherished in different ways. Stainless steel crockery in India is widely used in high end and high street restaurant settings. Plastic cutlery or paper plates are not mainstream. This may not be a consciously sustainable environmentally respectful choice. Stainless steel crockery for casual and celebratory dinners alike is a traditional, long lasting and economical custom. Their use is deeply embedded in Indian culture, and passed down generations. Its associations provide meaning and historical value, and it just happens to be sustainable a great example of reuse to avoid material waste in the food industry, despite the rise in western ideals of throwaway convenience culture that continues to percolate preconceptions of progress in many parts of the world.

In Japan the concept of luxury is distinct to other countries including the US, where a comfortable life is often linked to material wealth. The Japanese concept of whittling down one’s possessions and “Danshari” has been around far longer than Marie Kondo’s interventions. Many parts of Japanese society aspire to living minimalistically, in small and efficiently designed apartments with multifunctional products and furniture. This isn’t necessarily practised to consciously take care of the planet, but rather as a way of living that associates humble standards with great quality of life. The ‘less is more’ logic runs in parallel with the Japanese belief in the interconnectedness between man and nature, also common in many eastern countries including China and India. With this in mind, the concept of ‘sustainability’ can often feel imported from the West, as a ‘remedy’ for the modern ills of industrial society: instant gratification, waste, overproduction and overconsumption.

Colette Pichon Battle, climate activist, lawyer, and generational native of the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, shares this view of the modern ills of a post industrial society. In conversation with Krista Tippet, Colette reminds us that we have lost connection with our basic needs, and how we need to rethink our standards of living.

“We must have the courage to admit we have taken too much

It’s hard living in this country…even the response to disaster or harm is to go purchase something.

We don’t even know what we’re doing.

We do it unconsciously.

We are so wealthy.

We have to examine our comfort.

‘Just go buy it, go take it, it’s yours to take.’

It takes a lot of courage to examine that.

We’d have to examine our comfort, what we’ve worked all our lives for.

Our standards.

We have harmful standards harming the planet.

We love our comfort and our freedom…we are at the tip of the blame knife.

Our consumption is causing this problem.

If we believe in luck…luck comes responsibility.

We don’t just get to recycle and feel good about ourselves.

We have to show up at the hard places.

We are the engine of the harm.What’s the line between the blame that stops you from action and the acknowledgement that catapults you to do the right thing?”

I believe that line can be found in at least two places. One is represented by activists including Colette Pichon Battle or Scientist Rebellion (inspired by Extinction Rebellion), who embody and promote environmental action day to day, with every fibre of their being. As for other members of our global community that may feel guilt ridden, put off, or tired by the S word – the line between the blame that prevents action and the acknowledgement that catapults you to do the right thing may not be purely about conscious morality. Rather, it may be about redefining a good life by embracing our basic needs and leaning into joy, community, connection and cultural tradition to inform habit creation grounded in environmentally consequential activities.

A call for designers and creators:

Understanding human behaviour lies at the heart of responses to climate change. Some behavioural shifts need to be more extreme. By contrast, many environmentally relevant behavioural patterns are and can be frequent, stable, and persistent. Examining the key ingredients for repetitive feel good rituals could very well inform the shell within which the pearl of environmental prosperity can grow. As we know, the impact and effects of our value based decisions are often not immediately visible or tangible. But the pearl grows nonetheless, and mother nature does not rush for her to reveal herself.

As a final reflection, I encourage our creative communities to embrace the following three considerations:

- To reflect on practices in your own culture, or cultures distinct to your own. What traditions and rituals happen to be environmentally prosperous? What can we learn from them?

- To analyse behavioural patterns that are routines embedded in present everyday life (even if some are more environmentally relevant than others), prior to focusing on behavioural change for the sake of the S word. What can we extract from these patterns to inform environmentally consequential design solutions?

- To rethink the reliability and dependency on the s word. You may even come up with alternative pearls of wisdom.

I hope you enjoy the process.