Fire and Ice. Sun and Moon. Yin and Yang. Good and Evil. Heaven and Hell. From childhood, stories we are told are sewn with the thread of contrast, duality and “opposite” characters with motives and lessons as old as time. We learn to analyse and differentiate between behaviours and choices that are beneficial or detrimental to the story and its characters. Eventually we may learn that, whilst the distinction between good and evil is a fundamental truth, the human experience is rarely purely one or the other. One character can be made up of many contrasting characteristics, paradoxical by nature and even contradictory. For example, some characters are both victims and perpetrators of pain.

Contrasting truths or contradictions are often the source of joy or delight in any form of food, art, music or design. A contrasting truth can be found in the double meaning of a word in your favourite poem or song. It’s the anti-hero in the series you’re watching, both brilliantly funny and carrying deep pain which they inflict on others. It’s the lightness of your favourite coffee cup that is designed to look luxuriously heavy. It’s that unexpected classical melody that elevates your favourite R&B track. It’s the umami flavour of a miso coconut curry that is deliciously savoury whilst also being subtly sweet. It’s what the late multidisciplinary designer Virgil Abloh described as “the compromise between two distinct similar or dissimilar notions.” It’s in the opening page of Charles Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” – Charles Dickens, The Tale of Two Cities, 1859

Dickens’ contrasting truths, or harmonising contradictions, are at the heart of the human condition and remain as accurate today as they did in 1859. It takes humility to recognise our own contrasts, such as the best and worst in ourselves. From one paradoxical human to another, my ask is that as you read this piece, you consider your own harmonising contradictions as dualities that are in flux. Whilst some attributes may be more fixed than others, they are capable of evolving and shapeshifting. Alternative perspectives can expand our horizons about a certain cause we care about, a group of other humans we share this earth with, and possibly even ourselves. There are four parts to this thought piece, and each ends with “How Might We?” statements, a popular ideation tool used by designers and researchers to reimagine how problems can be solved in a forward-looking future state scenario.

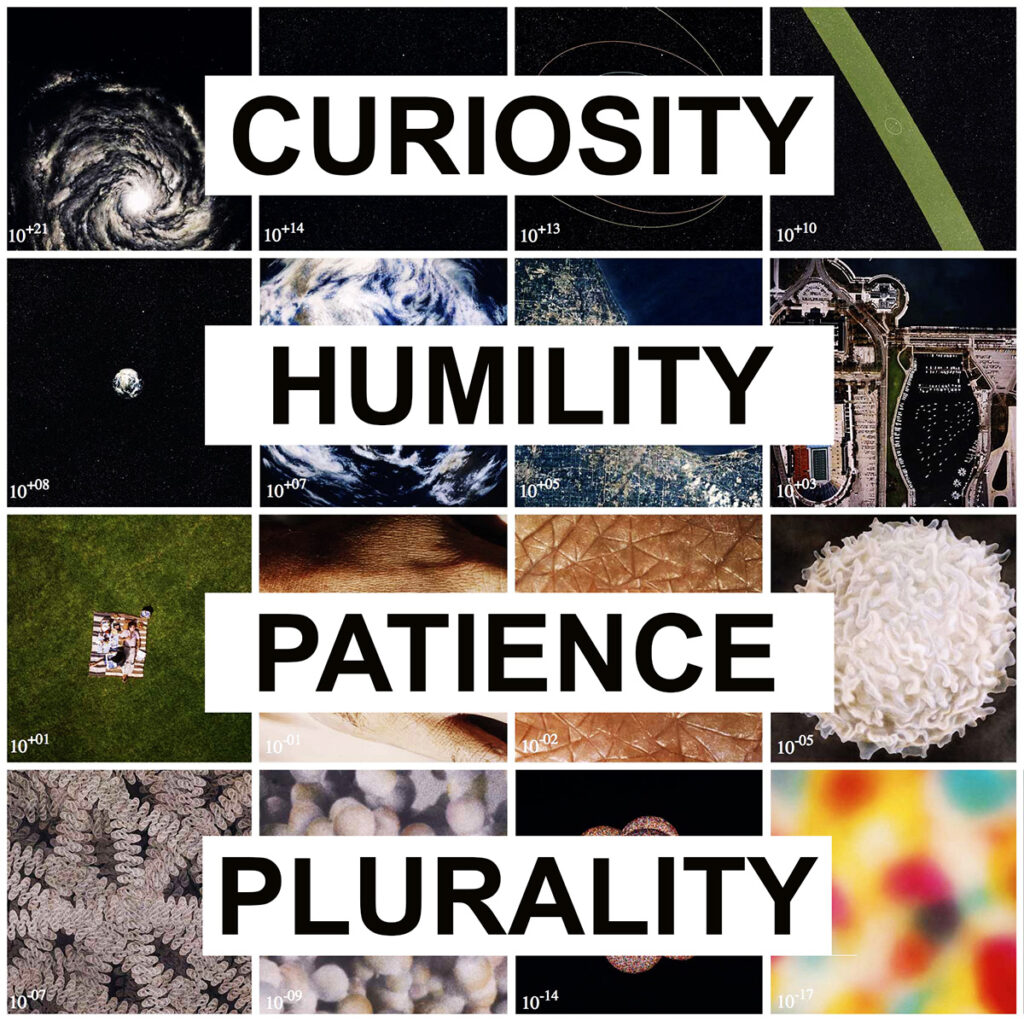

We’re at a cultural saturation point (or have been for some time) in which online discourse, so heavily dominated by polarized viewpoints and deterministic morality, is shaping how we communicate with each other. The quest for righteousness leaves conversations void of nuance and mercy, something Dr William Brady breaks down in conversation with Brené Brown. We’re lacking the patience to learn and respect multiple perspectives or contrasting truths. Consequently, it’s becoming the cultural norm to launch into chosen fortresses of fixed concrete and perceived singular moral superiority, instead of choosing a porous way of thinking, founded in curiosity and humility for experiences or opinions alternative to our own. Not only are curiosity and humility fundamental for creativity, they can also help us see through our own fortresses, to the several sides and perspectives that lay on the horizon.

We all share the same ground.

– David Lynch“The side effect of expanding consciousness is that negativity starts to evaporate; it goes away like darkness when you turn on a light.”

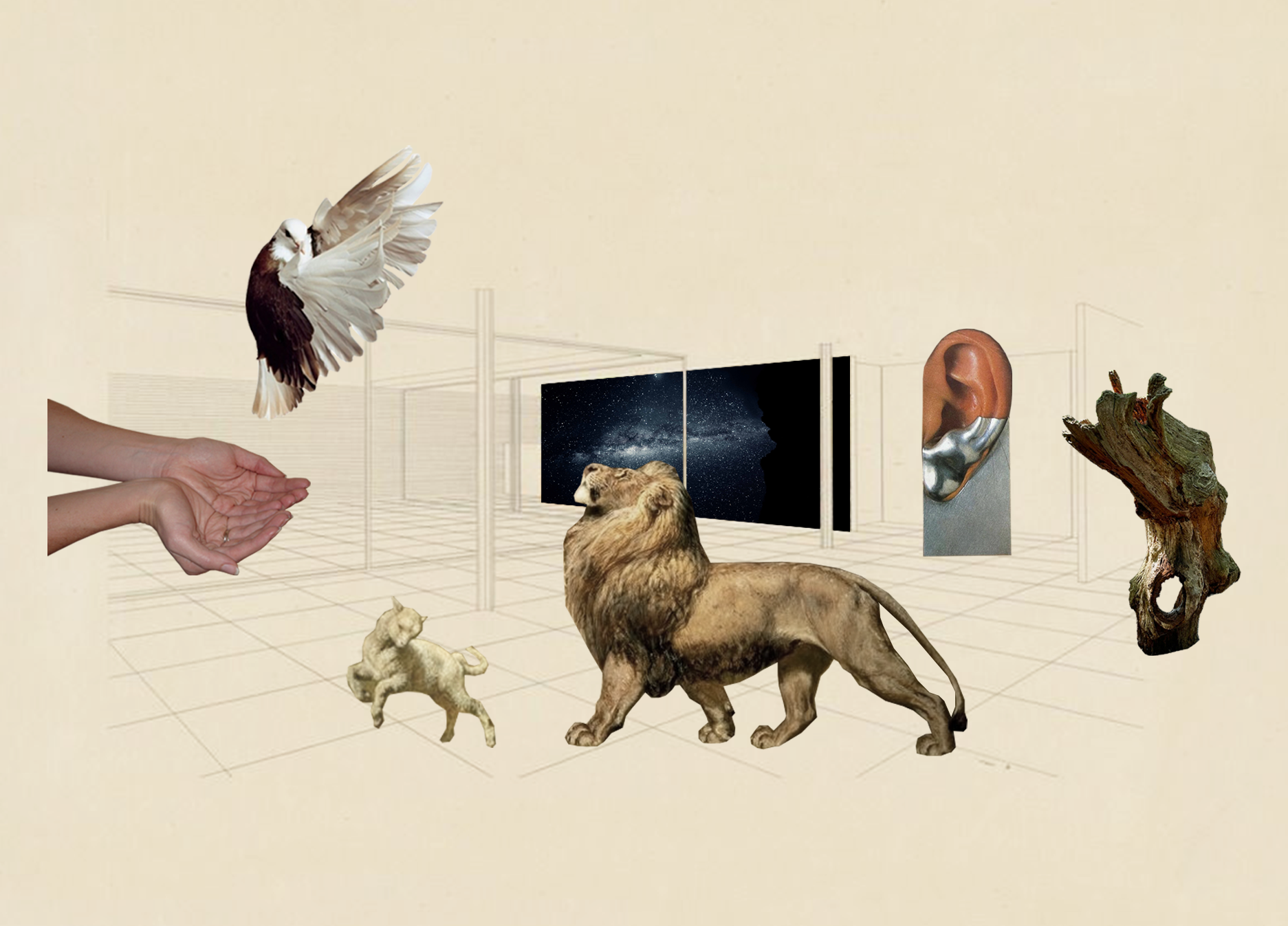

So what can design teach us about the positive impact of embracing contrasting truths? We can take inspiration from design research processes and the unbiased mindset needed to problem solve for as many people as possible. These processes start with accepting that your opinion is not the most important one in the room. Any designer or creative who severely restricts alternative perspectives, risks limiting their product, service or space’s potential for impact, and consequently making something that does not meet a range of diverse human needs. Luckily, curiosity can be a saving grace and empowering tool.

PART 1: Be curious before conclusive

To design any product or experience in 2024, without speaking to a group of representative people who it is meant to serve (also known as the product’s “users”) would be nothing short of ludicrous. Principles of human centred design grounded in behavioural science, sociology and anthropology are important to integrate into the design process, to garner reliable evidence on what works or doesn’t work about a product experience, as well as any insights that lie between or outside of those two contrasts.

Designers and researchers prepare questionnaires and interview guides through the lens of curiosity and assumptions, to gather as holistic and honest a picture as possible of people’s experience using said product or service. Responses are then analysed, to improve the design accordingly, and tested again with a new group of people until the most robust design improvements are achieved. Designers and researchers need to assess what may go unsaid, and stay open-minded regarding what may need further investigation. We are constantly reminded to challenge our own biases, to make sure we are doing justice to the truth of the individual and collective experiences we are documenting.

It’s not about what we think. It’s about identifying patterns and interweaving multiple perspectives to prioritise key improvements in order to make the product or service better for as many people as possible. If designers do not see outside of themselves and their own belief systems when designing, they threaten to create products, services and experiences riddled with bias that do not provide value to as many people as possible (if only more politicians and world leaders thought this way). Designers and researchers have a moral contract to hold each other accountable for zooming out and seeing things from afar for what they are, beyond their own personal point of view. In practice this involves leaning into the words of Epictetus, a 1st century C.E. Greek philosopher; “We have two eyes, two ears and one mouth so we can look and listen twice as much as we speak.”

Anthropologist and professor Christopher Davis describes the foundational principle of curiosity in how we can better understand other humans and cultures, in her taster lecture on witchcraft as part of her former SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, London) lecture series;

“Anthropologists ask two basic questions. One of them is, ‘How can this be?’

This question means we aren’t reliant on the fact that people are strange or wrong, belittling their way of thinking. You can ask this question about any situation. You can be at a dinner at home, with friends, in the library and ask, ‘How can this be?’ It can draw you to all the elements that make a situation what it is…

It’s a question that brings strange things closer, and makes familiar things feel strange.

– Christopher DavisIn that overlap, between the strange and the familiar, is where anthropology is at its best…to perceive things differently and to be interested in different things.”

The following Dr. Adam Grant quote builds on these research principles, and his words are not just for designers and researchers. Grant’s message is for everyone and anyone who wants to cultivate their awareness, expand their universe and consequently the richness of their life.

“How to keep an open mind:

1. Think like a scientist: treat your opinions as hypotheses and decisions as experiments.

2. Embrace confident humility: argue like you’re right, listen like you’re wrong

3. Build a challenge network: seek out people who sharpen your reasoning

4. Follow people you disagree with on social media. You want people who reach different conclusions to you, but you respect the integrity of their thought process…Who are the people who before I knew their answer, I would be impressed by the depth and thoroughness of their reflection and analysis, regardless of the conclusions they reach?”

- How might we be more unbiased and keep our minds curious about a range of lived experiences related to a certain topic before drawing a conclusion?

- How might we prioritise other perspectives before our own opinions or assumptions?

- How might we improve a situation or scenario in as representative a way as possible?

PART 2: Adopt the humility and expertise of an amateur

Amateur: a person who does something without professional skill or experience (Google definition)

Amateur: from French amateur “one who admires or is devoted to something,” derived from Latin amare “to love” (Etymology)

The former Google definition of amateur is the one we are most likely more familiar with. To lack skill or be described as unprofessional or inept is far from a compliment. However, the etymology of the word describes an amateur as someone who is devoted to something. True to the topic of contrasting truths and contradictions, I would like us to consider the two above definitions side by side; such as a devoted person who lacks experience in what they are devoted to. This does not make this person unprofessional or ill equipped to do the job, rather, their very “outsiderness” can often help in identifying design opportunities beyond the realms of what is considered possible. In other words, sometimes experts are too close to a problem to solve it, and being an inexperienced devotee to a topic is a contrast that can result in wonderous outcomes.

For example, many of the most successful and transformative startups were created by outsiders to their industries. Airbnb wasn’t started by a hotel chain or travel agency, Uber wasn’t started by a cab company. Why do internal experts in their industries miss these opportunities? Often it’s hard for experts to see innovative changes in their industries because it requires them to challenge their own assumptions that had previously served them well.

This is not a case for anti-expertise. Experts and specialists are fundamental to make any idea a reality. The appreciation for amateurism comes from its potential to increase collaboration to solve some of today’s most pressing challenges. For example, a room of biologists with similar academic backgrounds, focused on farming algae for carbon capture, are unlikely to provide each other radically different perspectives. However, a nutritionist or material scientist working with marine plant life will have enough foundational knowledge to understand what the biologists are doing, without the baggage of the field’s established assumptions. As a result, the additional perspectives and design output possibilities multiply, for example, identifying how a byproduct of algae farming can be used for its nutritional value, or as a building material and so on.

What does amateurism have to do with embracing contrasting truths? It is a reminder that great design, creativity, fruitful collaboration and responsible representation needed to unearth new ideas and solve problems in as valuable a way as possible, often requires working with and listening to those outside the area of expertise. Because all experts have blind spots, it’s necessary to cure those blind spots with new perspectives that sit outside of our histories, belief systems, education and view of the world. If we’re lucky, these alternative perspectives will challenge or elevate our existing opinions on the subject at hand. If we’re luckier, a contrasting opinion could give rise to a brilliant idea or solve a problem in a new way.

We can all strive to be an expert in what we do, whilst guided by the spirit of an amateur. We would be doing a great disservice to ourselves, each other and the power of creativity if we were to limit our thinking to fixed indestructible fortresses of perceived expertise or superiority in a subject, in which any remotely different angle is not only unwelcome, but deemed wrong. Africa Brooke extends this message beyond a topic of expertise, to that of a worldview;

– Africa Brooke“Do not fall into the trap of believing that those who view the world through a different lens to you, are automatically your enemy. In a world that profits from us being disconnected from ourselves and each other; give people the grace to surprise you. Walk out into the world trusting that it’s entirely possible for someone sitting on the ‘other side’ of the aisle to offer something that enriches and expands your own worldview.”

Keeping Brooke’s message of giving people the grace to surprise you in mind, musician, writer and rockstar Nick Cave shares a similar sentiment in his September 2023 Red Hand Files Newsletter, about two qualities he believes can improve one’s life:

“The first is humility. Humility amounts to an understanding that the world is not divided into good and bad people, but rather it is made up of all manner of individuals, each broken in their own way, each caught up in the common human struggle and each having the capacity to do both terrible and beautiful things. If we truly comprehend and acknowledge that we are all imperfect creatures, we find that we become more tolerant and accepting of others’ shortcomings and the world appears less dissonant, less isolating, less threatening.

The other quality is curiosity. If we look with curiosity at people who do not share our values, they become interesting rather than threatening. As I’ve grown older I’ve learnt that the world and the people in it are surprisingly interesting, and that the more you look and listen, the more interesting they become. Cultivating a questioning mind, of which conversation is the chief instrument, enriches our relationship with the world. Having a conversation with someone I may disagree with is, I have come to find, a great, life embracing pleasure…

Love, Nick…My advice, then, is to try to make more use of humility and curiosity – these attributes have a softening effect on our sometimes inflexible and isolating value systems. They allow us to remain true to our temporary selves but fluid and playful with our dealings with this strange and ever-changing world.

Nick Cave’s message reminds us that we are constantly evolving, and that our temporary selves deserve to be more fluid, and perhaps even playful in our dedication to addressing the challenges we come across in our chaotic world. The power of play in design and problem solving, teaches us to use our imagination, adopt different perspectives and collaborate better with others. Play is also closely linked to trialling out multiple versions of a design solution through the process of iteration and testing with different ways a product or service can come to life.

Building on Nick Cave’s message on humility, journalist, author and professor David Brooks sheds light on humility or “the knowingness of our unknowing” in his book, A Road to Character. Brooks describes humility to be as fundamental as the air we breathe, should we want to live a full and moral life. Published in 2015, Brooks stated, “I wrote [A Road to Character], to be honest, to save my own soul.”

“People who are humble about their own nature are moral realists. Moral realists are aware that we are built from ‘crooked timber’ from Immanuel Kant’s famous line, ‘out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made…’

– David BrooksPeople in this ‘crooked-timber’ school of humanity have an acute awareness of their own flaws and believe that character is built on the struggle against their own weaknesses. As Thomas Merton wrote, ‘Souls are like athletes that need opponents worthy of them, if they are to be tried and extended and pushed to the full use of their powers.’”

- How might we live with humility and be open and playful with the evolutionary nature of our own values?

- How might we appreciate an alternative or opposing opinion as interesting over threatening?

- How might we prioritise finding common ground?

- How might we prevent limiting our creativity and knowledge to inflexible or isolating value systems?

PART 3: Use patience as a superpower in our fast moving world

Author and journalist Oliver Burkeman writes about humans’ relationship with time, and how despite the average human lifespan being, in his words, “absurdly short” (about 80 years old), our perception of the time we have and how we organise it often leaves us feeling more busy, distracted and isolated from each other. In Burkeman’s BBC Maestro lecture series, he breaks down core teachings from his book Four Thousand Weeks, including prioritisation and patience in relation to how we can live a fulfilling life.

One key takeaway from his lesson on patience starts with the acknowledgment that in the modern world almost everything is geared for speed and moves quickly. Exercising patience in our fast moving environments becomes a power to resist the pace at which everything and everybody is moving – or forming opinions. To be able to find that quiet moment of reflection, according to Burkeman, will result in better work, more enjoyment in life, and problems solved more effectively.

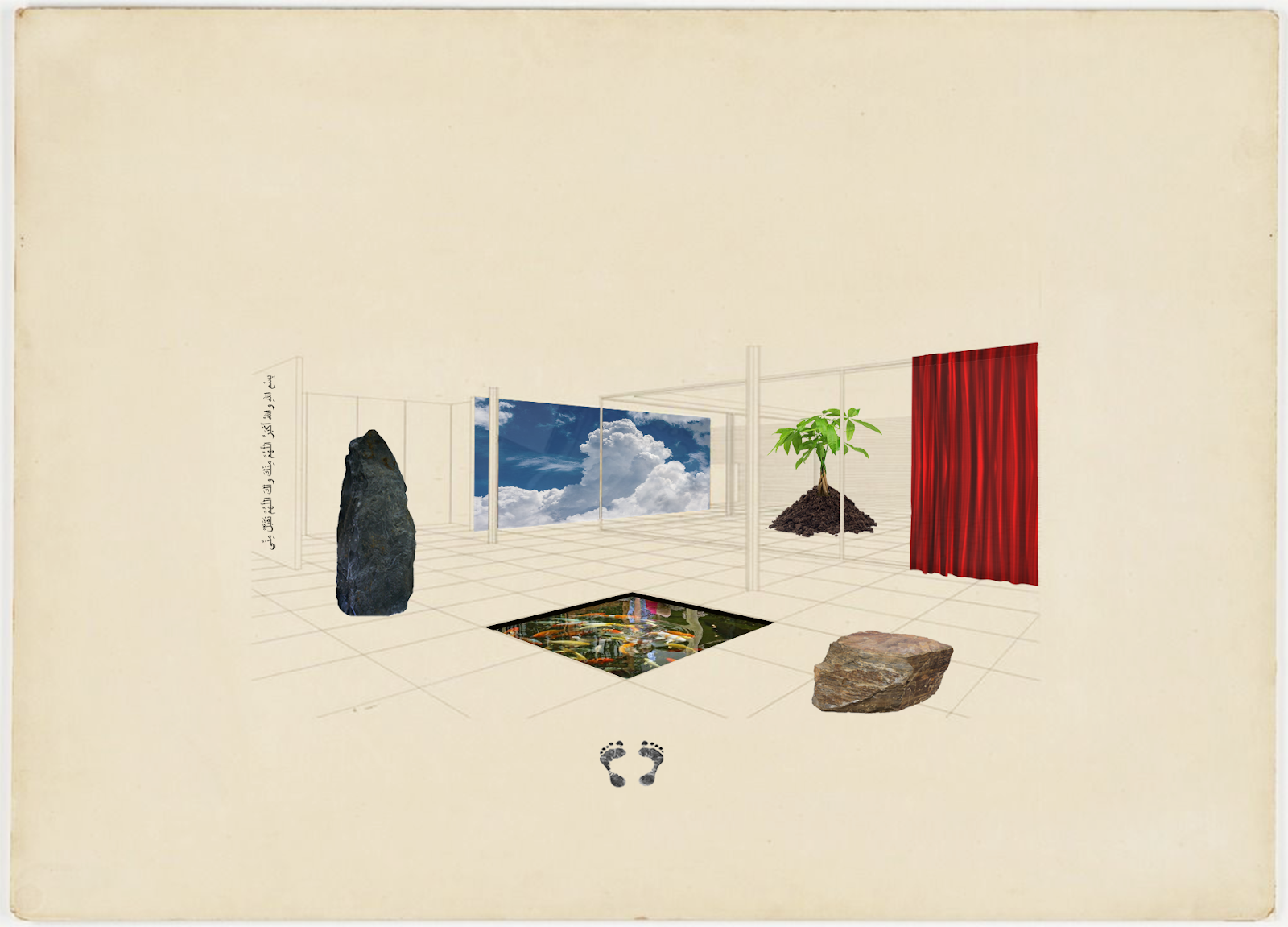

One way Burkeman learnt about the positive impact of patience, was from a practice taught by art historian and professor, Jennifer Roberts, of Harvard University. Roberts asks all of her incoming art history students to first find a painting or sculpture in a museum or art gallery. The next step of the assignment is to then look at their chosen painting or sculpture for three hours straight. Sound absurd? In some ways it is. Most people receiving this instruction would be outraged. It feels unthinkable, especially in the era in which we live, to spend three hours looking at a sculpture or painting. However, Burkeman describes this length of time as purposefully chosen by Roberts, because of what she has learnt about the fast moving world in which her students have grown up in. Roberts knows she needs to direct her students to slow down to learn an in-depth appreciation of art and a way of seeing, believing a person hasn’t necessarily taken in a painting or sculpture by just looking at it.

Oliver Burkeman took on this exercise, choosing a painting by Degas. Burkeman describes the first 45 minutes as being deeply intolerable. On the other side of the discomfort however, Burkeman then says he literally began to see things. Objects, lines, shadows and people that he had not seen in the first 45 minutes. Which left him with a heightened sense of appreciation and understanding for the complex layers, colours and combinations in the painting. For anyone interested in taking on this counter-cultural challenge, whilst you are not allowed to use your phone, you can indeed take notes of the details you uncover over the three hour period.

Beyond time and patience, the added factor in Jennifer Roberts’ art history exercise is one of silence. Mr Rogers, American TV host and minister who hosted the preschool television series Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (1968 to 2001) sheds some light on the value silence had in his life, and in relation to the noisy world we live in. In an interview with Charlie Rose in 1994, Rose asks Rogers “Who has made a difference in your life?” Rogers responds as follows:

– Fred Rogers“A lot of people who have allowed me to have some silence. I don’t think we give that gift very much anymore. I am very concerned that our society is much more interested in information than wonder, noise rather than silence. In our business [of television], how do we encourage reflection?…Oh my this is a noisy world.”

- How might we prioritise time to learn about the multiple layers and perspectives of a given subject?

- How might we embrace awe and wonder over information and noise? What myriad of contrasts and complexities would reveal themselves?

- How might we gift ourselves and each other the time to reflect and observe a topic with patience instead of forming an opinion at speed?

- How might we apply three hours of observation and study on one source of visual or verbal information before drawing a temporary conclusion?

PART 4: Put plurality over singularity

The term Overview Effect was coined by author Frank White to describe the experience of seeing firsthand the reality of the Earth in space, which is immediately understood to be a tiny, fragile ball of life, “hanging in the void,” shielded and nourished by a paper-thin atmosphere. From space, national boundaries vanish, the conflicts that divide people become less important. Differences are diluted and our commonality in our shared home stands out when we look at our world from a distance, similar to the awe-inspiring impact of the recent solar eclipse. We see our Mother Earth carry multiple experiences all in one place—an overwhelming range and simple unity all at once. As humans, we hold the singularity of the planet we share hand in hand with the plurality of our various lived experiences.

Physicist and author Carlo Rovelli elevates the beauty of plurality in our world, in his book The Order of Time, by explaining that scientifically speaking, our world is made up of a network of multiple events, not singular entities.

“We cannot think of the physical world as if it were made of things, of entities, separate from each other. It simply doesn’t work…What works instead is thinking about the world as a network of events. Simple events, and more complex events that can be disassembled into combinations of simpler ones, but their plurality is a common denominator.

– Carlo RovelliA few examples: a war is not a thing, it’s a sequence of events. A storm is not a thing, it’s a collection of occurrences. A cloud above a mountain is not a thing, it is the condensation of humidity in the air that the wind blows over the mountain. A wave is not a thing, it is a movement of water, and the water that forms it is always different. A family is not a thing, it’s a collection of relations, occurrences, feelings. And a human being? Of course it’s not a thing; like the cloud above the mountain, it’s a complex process in which food, information, light, words and so on enter and exit…”

In Rovelli’s poetic description of the plurality that makes up our world, we are called to see everything around us as layered in its multiplicity and in a constant state of motion, evolution and connection. In the words of the aforementioned lecture by anthropologist Christopher Davis, “As human beings we’re very adaptable—we’re not as permanent as we think we are.”

- How might we apply the concept of plurality to our own thinking and creative processes?

- How might we combine multiple elements and allow room for evolution in what we create?

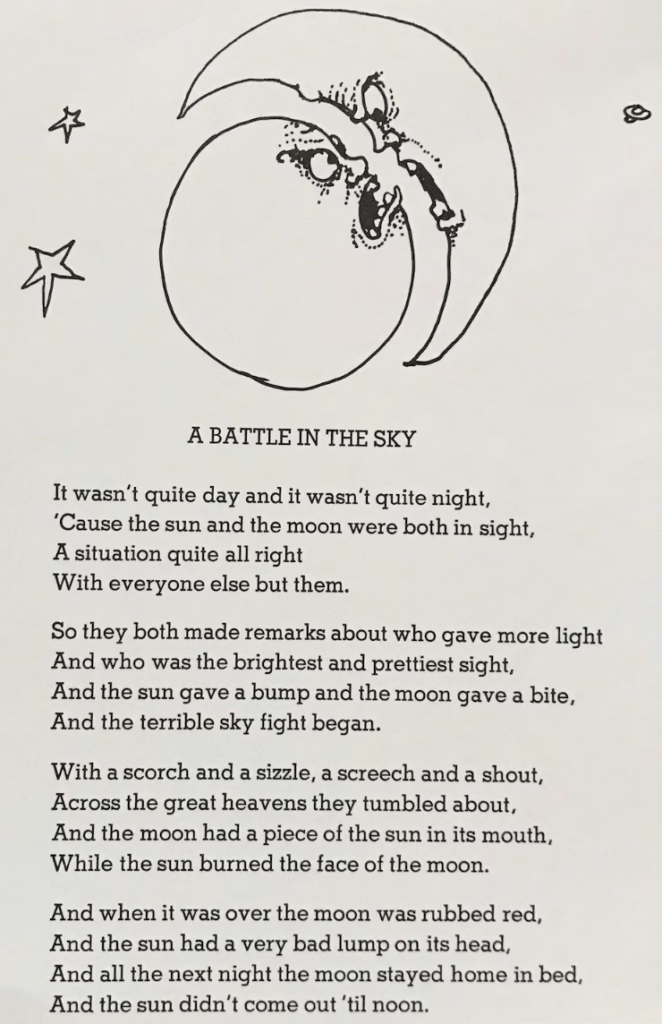

Shel Silverstein’s poem “A Battle in the Sky” from his children’s book Falling Up, 1996, is a slightly different take on physics. Silverstein illustrates the consequences of abandoning contrast and coexistence through two planetary beings that are in conflict; the sun and the moon. The battle in the sky resulted in a world without light. You and I need both the sun and the moon. They co-exist. If our sun is our truth, ideology, belief system, can we promise ourselves and each other to acknowledge and respect the value of the moon and other moons that may lay beyond our immediate line of sight? I hope that doing so will illuminate complex conversations, healthy discomfort, respectful disagreements and greater earthly coexistence.

In this spring season of 2024, may this month of northern hemisphere bloom bring you, fellow reader and evolving human organism, great peace of mind and an open heart.

May the contrasts and key phrases outlined in this thought piece help both you and I take inspiration from design processes and attitudinal approaches to converse with curiosity, listen with humility, and pause with reflection more often.

May we form our opinions at the pace of thawing ice, so pride and prejudice can melt and reveal a softer, malleable, porous mind. A mind that listens with intent, allows opinions to evolve, gifts itself and others grace, and respects distinct points of view.

May we dare to be counter-cultural. Our creativity and coexistence depends on this humble rebellion.

As a final offering, here are some sources that honour contrasting opinions and coexistence. Please feel free to get in touch with me if you have others you recommend.

Sources related to contrasting truths:

- BBC moral maze radio show and podcast: Combative, provocative and engaging live debate examining the moral issues behind one of the week’s news stories.

- Unlocking Us with Brené Brown and Dr. William Brady podcast, on Social Media, Moral Outrage, Polarization and how a new type of algorithm can foster points of view that are representative of people that don’t sit at the extremities

- The Rest is Politics podcast: Former Downing Street Director of Communications and Strategy Alastair Campbell and cabinet minister Rory Stewart join forces from across the political divide in their podcast The Rest is Politics. The show’s motto is “agree to disagree agreeably.”

- Can we learn to disagree better, The Economist

- What Do YOU Think? How to agree to disagree and still be friends, children’s book by Matthew Syed

- The Week news publication: covers news stories from a range of political perspectives.