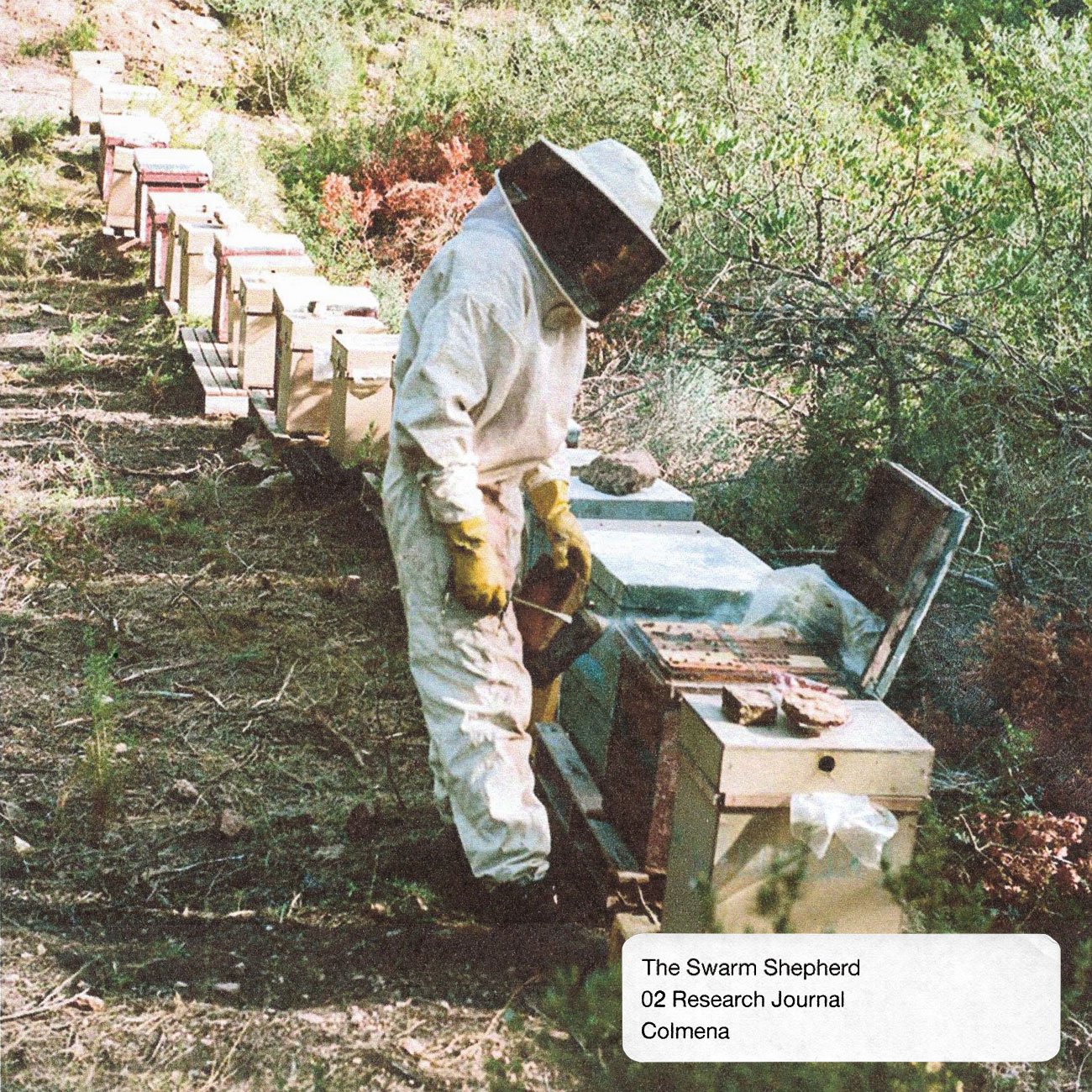

Colmena is a project by Pablo Bolumar that builds upon Swarm Shepherd, a geo-design project which proposes a new path for research on bee health in existing apiaries, aiming to expand bee cultures beyond honey production. Recognizing crisis as a catalyst for change, he aims to investigate alternative methods to bee farming and how these methods might cultivate new relationships with these social insects.

The first time I looked inside a beehive was in México. I was traveling around the country for a couple of exhibitions at the beginning of 2023, and at the same time I was starting to research about beecultures for my master’s dissertation. After three weeks of bumbling and eating tacos, we ended up in Oaxaca, a hot, dry, and colorful city in the south.

When we arrived my partner got sick, so we gave up on tourism and I decided to do some field research while she recovered. As a design researcher, I’m diving into the intersection between design and agricultural practices, specifically within bee farming. My goal is to establish a network of beekeepers to understand the realities of this practice, delving into its ecological, economic, and cultural dimensions as it evolves over the next decades.

My research is contextualized within the ongoing beekeeping crisis, marked by the deterioration of bee health and its abandonment due to economic challenges. Recognizing crisis as a catalyst for change, I aim to investigate alternative methods of bee farming and cultivate new relationships with these social insects.

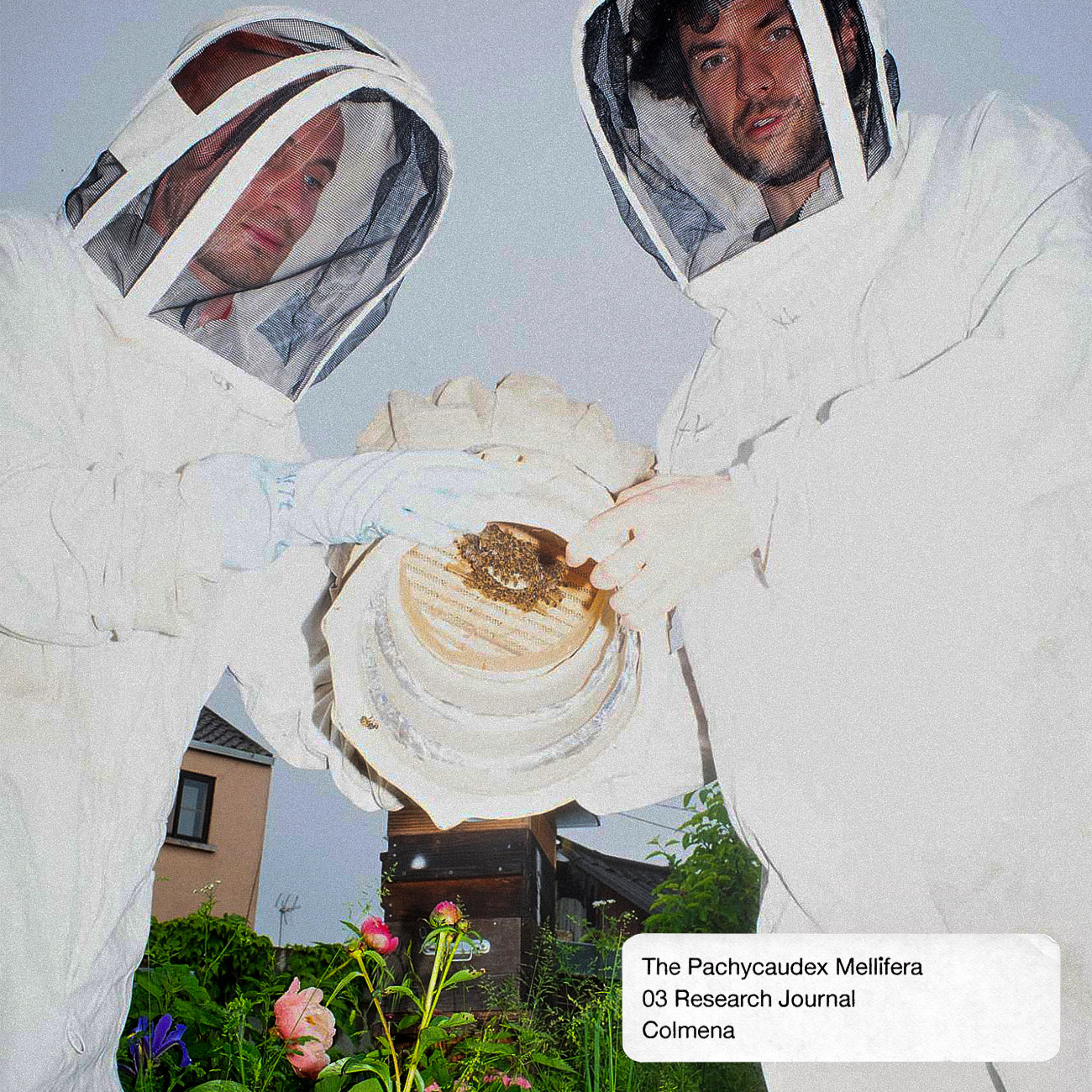

Our Airbnb host connected me with el señor Don Marcos, a generous and welcoming indigenous man teaching beekeeping to young teenagers at a farming school in the outskirts of the city. Papá Abeja (the self-proclaimed name was embroidered on his shirt) led a group of excited kids, unafraid of disturbing several bee colonies on a hot summer day.

For years, I had been curious about what lay inside a beehive. These gray boxes dotting the landscape only obscure the intricate reality of a bee colony. The cubic beehive is ubiquitous, you find it in every corner of the globe, and only later I learnt that this standardized object is a product of the principles of modern apiculture. The box allocates the frames, which deconstruct a honeybee nest into slices. While everyone has heard about the hexagons (they are actually circles stretched by gravity), picturing the actual structure of these insects’ nests would be quite challenging without this technology.

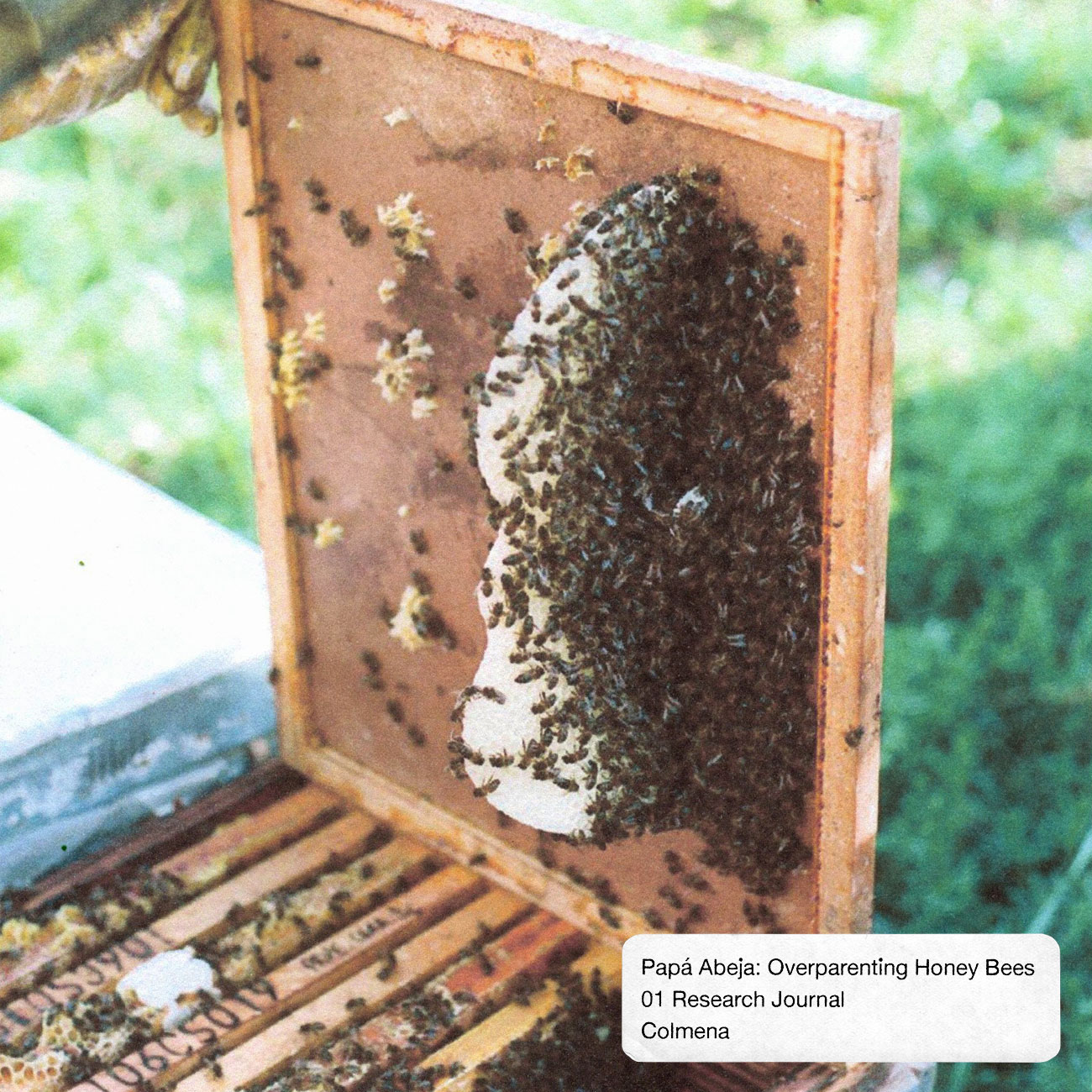

As Papá Abeja’s disciples opened a hive box, a buzzing cloud of bees emerged amid the smoke that was billowing from the smokers which were being manned by other students. When I managed to refocus on the hive, all I could see were parallel wooden bars covered in a sticky substance. Don Marcos began removing propolis and beeswax from one of the bars, pulling out a frame.

Sociobiologist Jurgen Tautz describes a bee colony as a superorganism comprising thousands of insects working collectively. The colony produces an external organ, the honeycomb, designed by the bees to support the entire group’s survival. This mass of beeswax is continually transforming into an organic storage device for brood and honey, while also serving as a shelter and a communication platform for the colony. I wonder, how did all of this end up in some sort of file cabinet?

Don Marcos examined both sides of the honeycomb-filled frame, observing and pointing out the queen’s spiral egg-laying pattern. The frame hive allows the manipulation of an otherwise sticky and complex bee structure, which would be impossible to access without damaging. Many beekeepers still argue that this technology developed 150 years ago, enables better pest monitoring and, therefore, improves colony health. After inspecting both sides of the frame, Papá Abeja brutally scraped the comb and sprayed it with water to “refresh” the colony.

A bee colony is remarkably intelligent and strives to maintain optimal conditions. In winter, the colony seals every tiny hole in the hive with propolis to prevent cold air from entering. Propolis is the sanitary concrete of honeybees, they use it to build and disinfect their nests, and is made of a mix of saliva, beeswax and botanical sources like tree sap or resin. In summer, bees bring water drops on their legs and fan the hive with their wings, creating a buzzing “beard” of bees at the hive entrance—their version of air conditioning. If bees are good builders, they are the best climate engineers, as the stalactite-like structures of the honeycomb follow cold and hot airflow currents. Attached to the top of a cavity, the honeycomb organ is built to retain a bag of heated and scented air with pheromones, crucial for the colony’s well-being and survival.

Papá Abeja opened another box from the top, releasing the scented and sanitized air from the hive, and removed all the beeswax bridges that his industrious insects had built for weeks between the frames. I remember Don Marcos explaining that a skilled beekeeper must keep the frames clean for easy removal. His well-intentioned yet occasionally disruptive interventions align with the set of unwritten principles of rational apiculture. What Papá Abeja learned and continues to impart to his students pertains to modern beekeeping, an intensive farming practice developed during the last two centuries that frequently clashes with the ingenious decisions of the colony. Bees operate autonomously, without anticipating any assistance.

Pablo Bolumar Plata is a designer and researcher focused on the transformation of material environments. His ongoing research in the apiaries analyzes the relationship between bee colonies and humans through spatial design, aiming to expand bee cultures beyond honey production.