Colmena is a project by Pablo Bolumar Plata that builds upon Swarm Shepherd, a project proposing alternative research in existing apiaries through material and spatial design, aiming to expand bee cultures beyond honey production. He is investigating alternative methods to bee farming, and how these methods might cultivate new relationships with these social insects.

Only after months of researching beekeeping did I understand its real meaning: to keep the bees inside the hive. “Bee-keeping”. Because trust me, they will try to leave at some point. It was spring of 2023, and I was visiting apiaries both in the Netherlands and Spain to conduct field research for my master’s dissertation. What I didn’t know yet is that it was just the beginning of the most active and exciting season for beekeepers, swarming season.

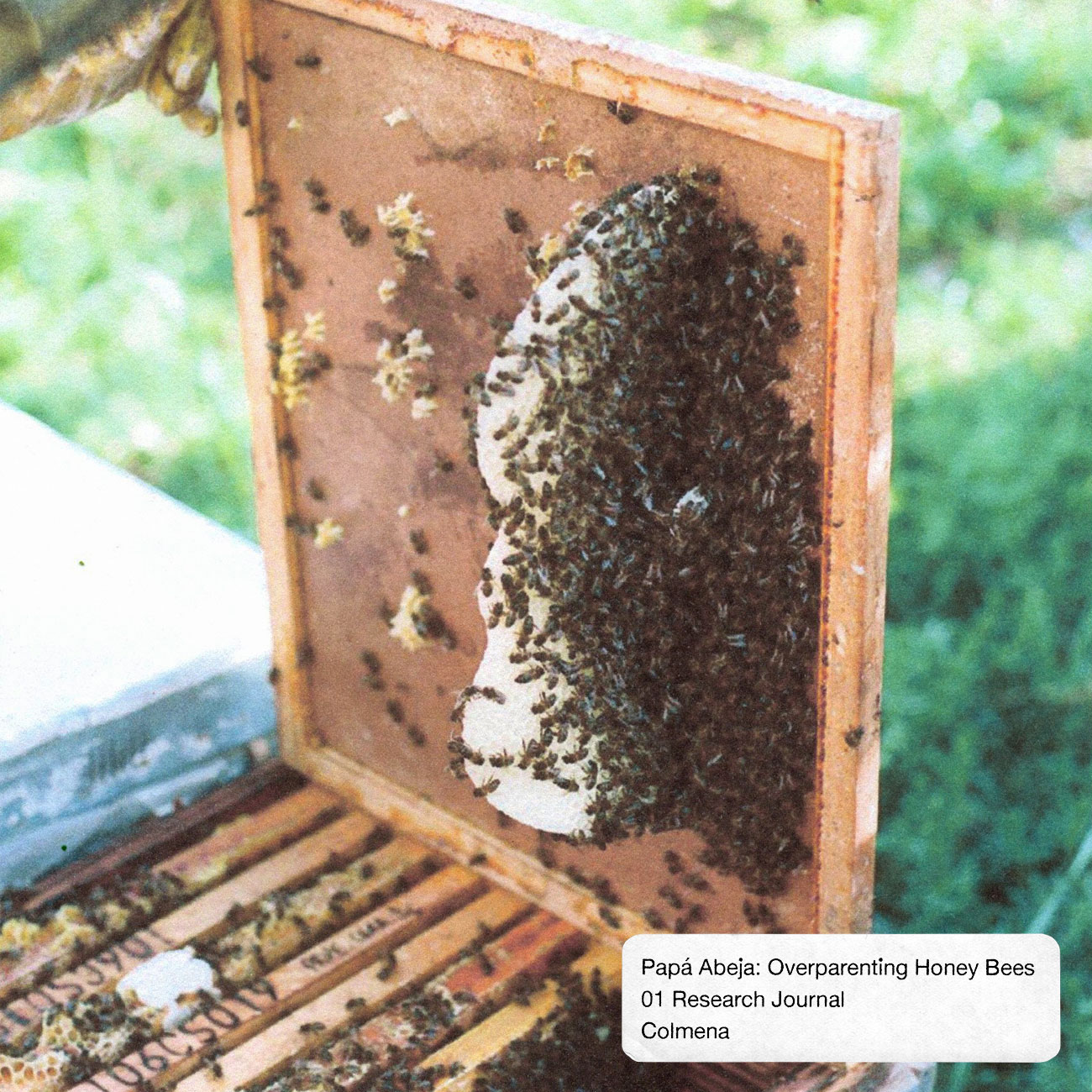

Swarming1: oh god, the nightmare of the beekeeper, “the devil”. In almost every beekeeping manual, it’s the enemy. To avoid swarming, you must check on the queen cells2 and break them. You must give the colonies space. You must give them ventilation. They might be too hot, so they will swarm. Or they might not have enough space. They swarm around 12 PM, in the hottest hour of the day. If they swarm, then half of the cattle is gone. Bad beekeeper. The nearby beekeepers will laugh at you. Or they will catch your swarm. The neighbors will complain when they nest inside their roofs, or in their windows, or inside their wooden floors. Another beekeeper will catch them, for sure. Your cattle, that took you so long to place inside your hive. We should avoid swarms at all costs. That’s what modern beekeeping is about.

- 1A great number of honey bees massed together emigrating together from a hive in company with a queen to start a new colony elsewhere.

- 2A type of cell raised away from the rest of the cells, where the new queens spend their juvenile stages as they develop from egg to larvae and then pupae. The workers feed the larvae on royal jelly.

But swarms are beautiful. Unexpected. Incredible to look at. So much bee, so many bees. They must be organized to do what they do so elegantly. And to find a spot that suits their size so nicely. By swarming, a bee colony splits into two or more colonies and it reproduces. It multiplies and diversifies the genetic line. It’s a honey bee thing to do, swarming. As they swarm, bee colonies spread over the landscape. They find a suitable home, with the best climate conditions, far from human reach (although humans will always eventually reach them). “Those hairless beasts, addicted to our honey!”, they must think. Bees try to spread over the landscape, to leave enough distance between colonies, to leave pollen for everyone, but no, humans will put them together, very together. So many colonies, on the same piece of land: hypercolonies.

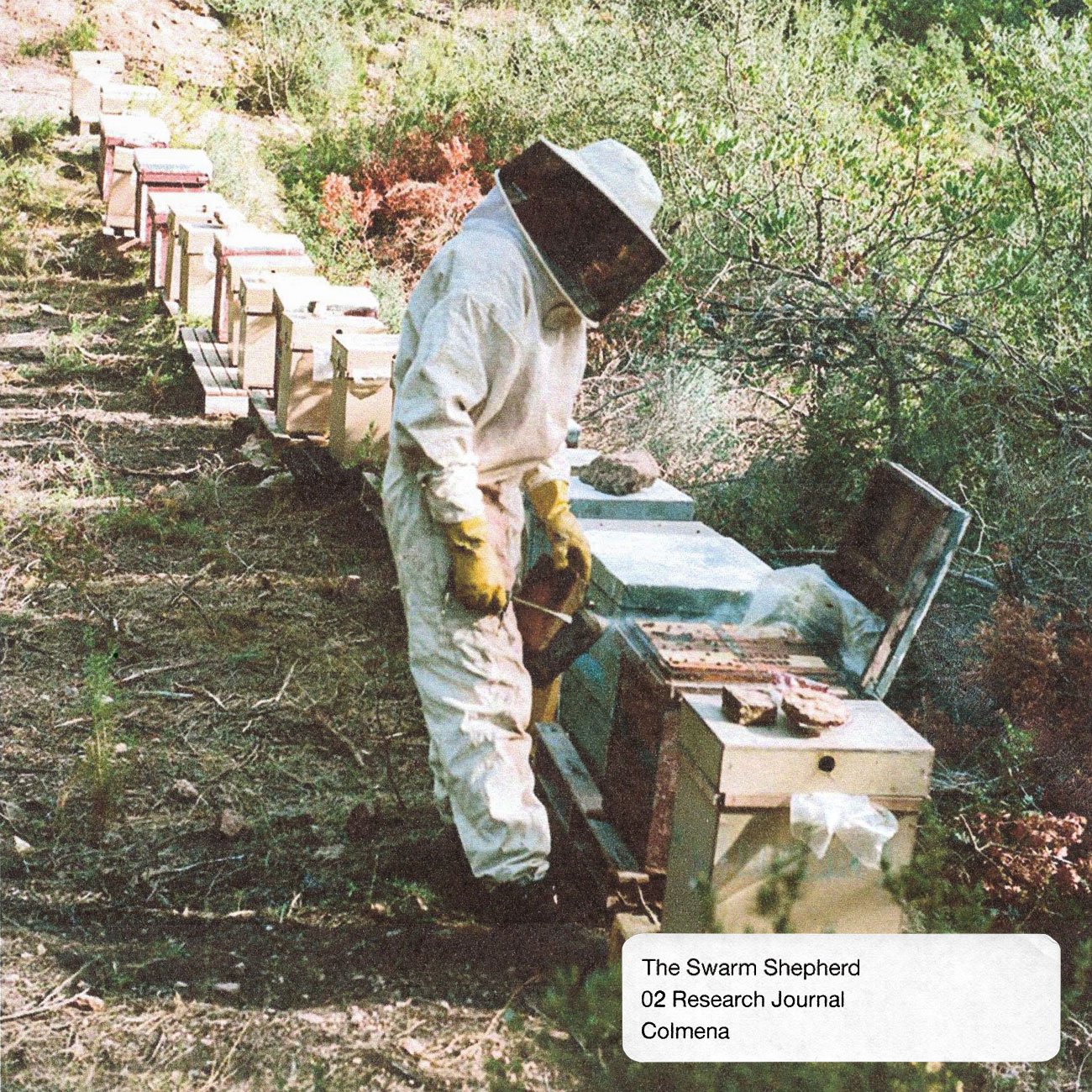

Beekeepers move their colonies around to search for more pollen because they want more honey, and different flavors too. Transhumance3 is called upon. Hives filling trucks, or perhaps a little van, or a pick-up with twelve boxes, all on the highway—it’s the beekeepers driving their bees around. Once, an elder beekeeper told me that what honey bees like the most is gas. Gasoline, in order to move around and taste all the different flavors, from monoculture fields, to abandoned fields, low mountains, high mountains, your grandma’s flowers, nectar, and sugar. But they wouldn’t drive a car and move themselves, would they? No. Beekeepers like to do that, commercial beekeepers, hungry beekeepers. They tie the beehives together, close the doors, and drive them around. The hypercolonies are in transit.

- 3The practice of moving livestock from one grazing ground to another in a seasonal cycle, typically to lowlands in winter and highlands in summer. In beekeeping, transhumance follows flowering seasons.

My friend Lolo brings their bees to the avocado flowering. WTF is an avocado flower? Must be as tasteless as its fruit. I have no idea. Either way, there are forty colonies in the same field. Lolo’s bees produce avocado honey. It’s yummy actually, tasteful, it does taste like avocado, more than the actual fruit. But not worth it, because Lolo’s friend got robbed of about 20 hives. I knew beekeepers robbed honey from their colonies, and also that honey bees robbed honey from other colonies, but beekeepers robbing other beekeepers of their colonies? That must be Karma. Hundreds of colonies all together, moving around… the universe didn’t want them all together. That must be it.

I’ve read about the detriments of the hypercolony, especially in moving them all together to a new place. Imagine a boat of tourists arriving in Venice, eating all the food in the city, and leaving with their stomachs full. Those poor Venetians. They will starve. That’s what happens to native pollinators, the cute little insects that go around doing the same thing as honey bees. In actuality, they do their thing way better than honey bees. Honey bees are generic pollinators, trained to gather as much pollen as possible as fast as possible. However, some insects have evolved in parallel to the plants they pollinate in their locality. Both these plants and insects have complementary organs, so when they gather nectar, the plants reproduce. For example, some orchid species can only be pollinated by male wasps, and to attract them, they’ve learnt to imitate the smell and appearance of female wasps. Male wasps provide pollination services to the orchids without even tasting the nectar. But honey bees are global, worldwide insects, pollen cheaters, so they don’t care. They will gather all the nectar, leaving nothing for the native insects, and without even pollinating most of the flowers. Some insects will starve, some might die, and some plants might die too. Honeybee colonies might die after depleting the ecosystem as well. They will eat everything, every type of nectar, in order to make honey for their beekeeper.

Thinking about keeping bees, and keeping them together for the convenience of the beekeeper, I thought: what about letting them swarm? Letting them spread over the territory? Making sure they have space and resources? Could they manage? Some beekeepers say that nowadays, honey bees can’t live unsupported by beekeepers. I think honey bees are very intelligent. In this scenario, they would not live in the “wild”, but instead inside human built structures. But of course, there are the neighbors. The neighbors! What if a swarm ends up in a cavity in their roof?…

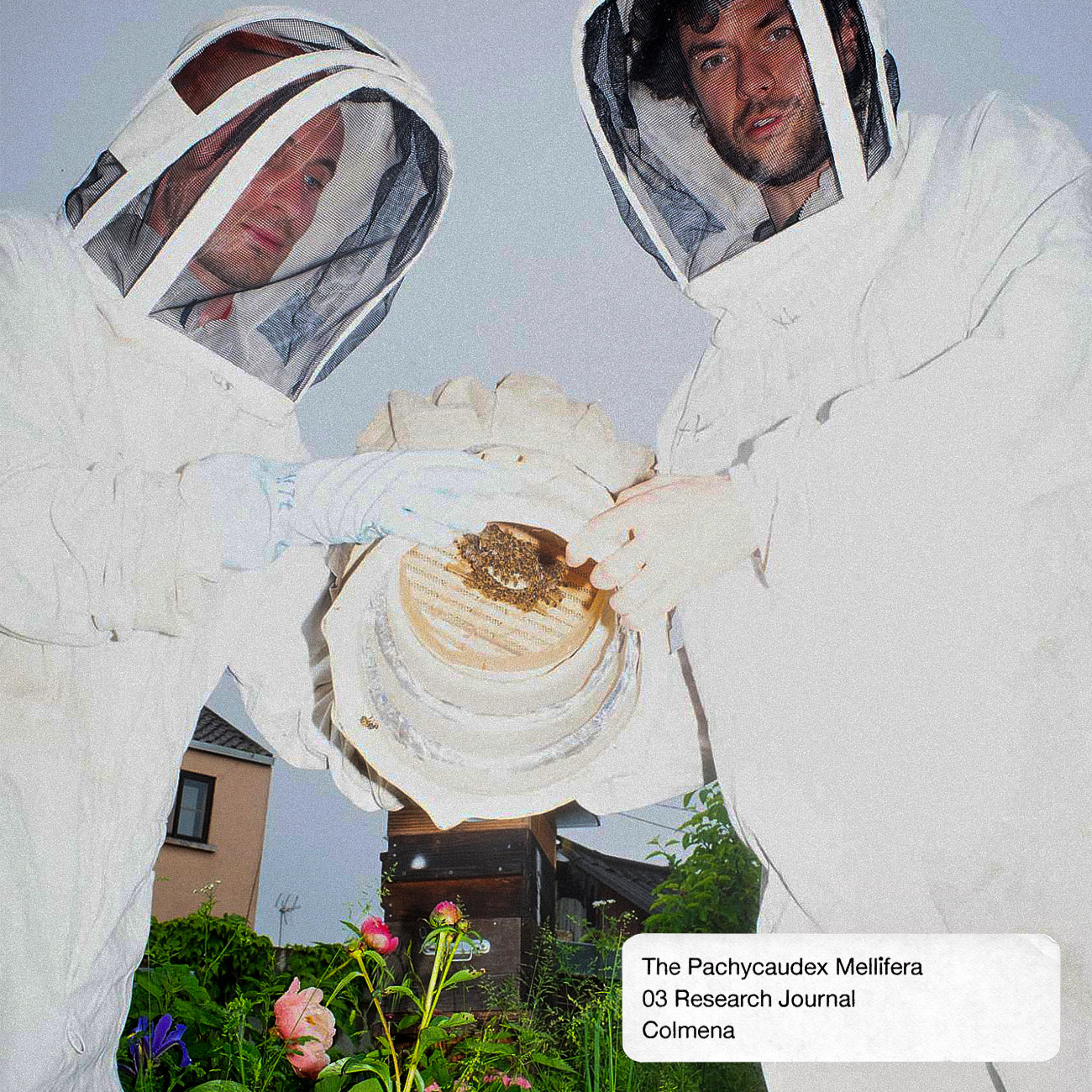

How about guiding the swarms? Or just letting them be? It would be easier than trying to keep them inside the hive, which just negates their nature. And what about following them, or rather making them follow you? Some sort of “shepherd”, instead of a “keeper”. I liked this idea of swarm guidance, instead of keeping the bees, forcing them inside. So, I took this speculative scenario and started thinking as a swarm shepherd. I would have swarm traps, lots of them, very different, made of all materials. Inexpensive and insulating materials, to make sure they’re warm in the winter and chill in the summer. I would place them everywhere, in safe spaces, so the neighbors don’t complain. With the swarm traps everywhere, in Spring the colonies should spread and reproduce, under the beekeeper’s, or the swarm shepherd’s guidance.

I made some swarm traps of waxed textile, so the honeybees would feel it’s their own structure. I placed them in a couple of apiaries in Valencia, Spain and Eindhoven, the Netherlands, during the swarming season. Scouting bees4 were attracted because the trap was infused with wax and lemongrass oil, which I learnt imitates the pheromones of a queen bee. They visited the trap, scouted it, probably commented about its design, and eventually left it. “Too thin, too cold”, they probably thought. A piece of textile, a beehive tent, what I was thinking? Maybe for a summer night, but not for an entire life cycle. My friend Lolo told me they like to feel safe and warm. Solid, climate stable, dark—a proper beehive.

- 4Mature female honey bees that help to direct the swarm to a new home. They’re elite foragers with a good understanding of the local area and excellent flying skills. They must search, return, and communicate their findings for the colony’s survival.

So I added some cork bark, for insulation purposes. There used to be cork bark hives, called “vasos” in Spain, which means glass, like a glass of water. They were cylindrical, following the shape of the cork bark—although there were some made of flat cork slabs, starting to look like a contemporary beehive box. Honey bees were cultivated there, without frames, with only some sticks to hold the honeycombs. When there would be enough bees and enough queen cells in the spring, they would take another hive and move half the population there with the old queen, making sure there were enough queen cells in the old hive. A colony split, which is a pre-swarm technique to keep the bees under control.

Pablo Bolumar Plata is a designer and researcher focused on the transformation of material environments. His ongoing research in the apiaries analyzes the relationship between bee colonies and humans through spatial design, aiming to expand bee cultures beyond honey production.