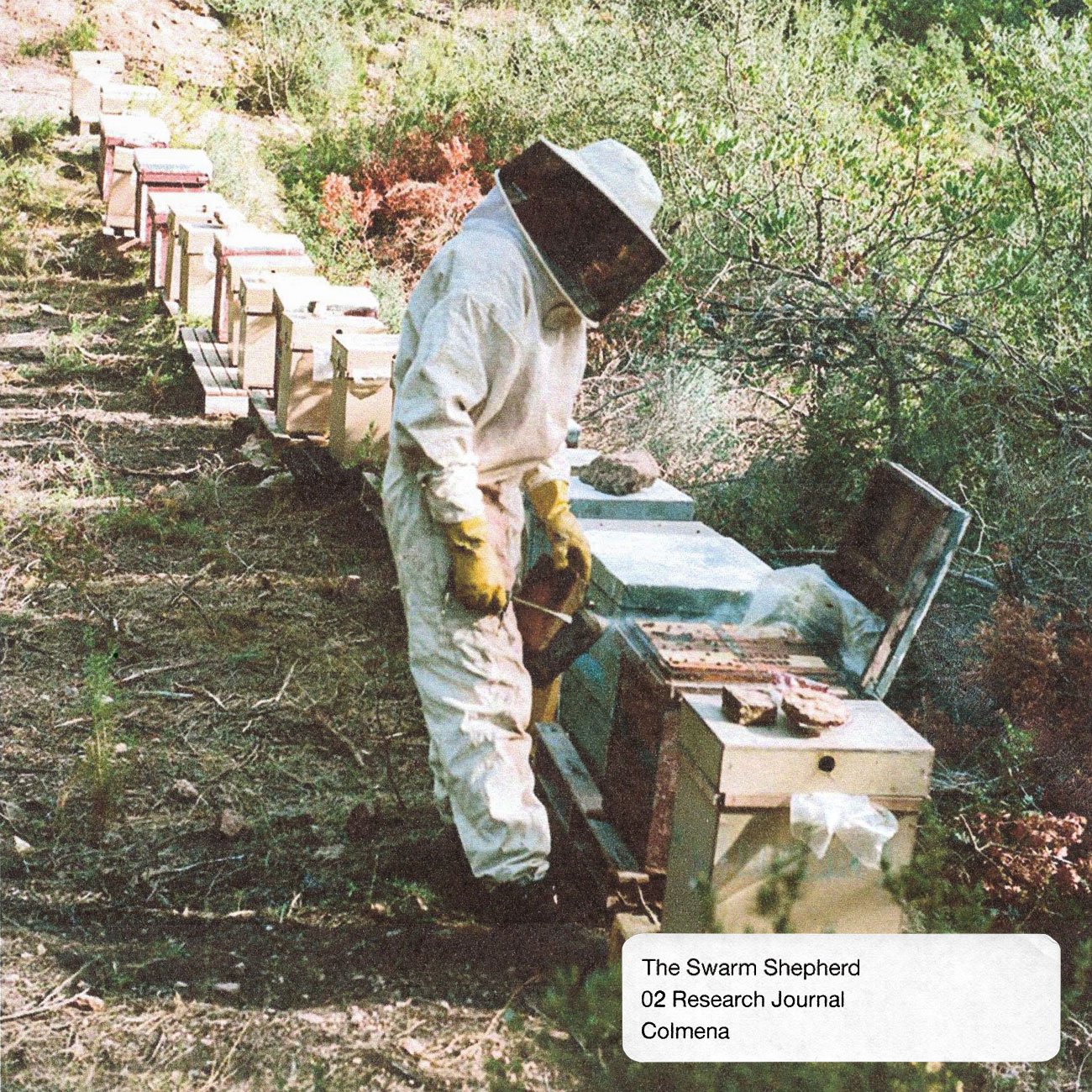

Colmena is a project by Pablo Bolumar Plata that builds upon Swarm Shepherd, a project proposing alternative research in existing apiaries through material and spatial design, aiming to expand bee cultures beyond honey production. He is investigating alternative methods to bee farming, and how these methods might cultivate new relationships with these social insects.

It was January of 2024, and my studio mate Raphael Serres approached me to start a collaboration. He is an eccentric and brilliant ceramicist and illustrator, and his artistic universe mixes plant and animal features into monster-like clay creatures that seem to come alive. We were both in a creative low and needed some fresh inputs in our work. Raphael was interested in learning about bees and designing a sculpture to host living things, and I really wanted to prototype something new, so we decided to work on a ceramic beehive.

We decided to work on a stack of cylindrical vases that would assemble into a vertical hive. Raphael started modelling right away, as he always does, and his gestures brought us into a conversation about evolution in the plant kingdom. Some spikes and leaf-like surfaces appeared, and all of a sudden we clearly saw a cactus shape.

Raphael knows a lot about plants. He mentioned his favorite plant family is the caudex type, a botanical group characteristic for a hollow water reservoir in their thick stem, like a baobab. We started wondering how the symbiosis of a caudex plant and a bee colony would interact.

Building upon our beekeeping and botanical knowledge, we started designing with a mixture of fantasy and natural logic: wild bee colonies used to nest in hollow tree trunks before human structures dominated the landscape, so it would have made sense that they could nest in a hollow stem of a caudex plant. If it would be a symbiotic relationship, our caudex plant would allow the colony to live inside in exchange for some of the honey the bees would produce. We began envisioning how over time, the plant would receive nutrients through their guests and develop defense mechanisms to protect the bee colony from predators like the Asian hornet. The spikes, a movable entrance borrowed from carnivorous plants, would ensure the bee colony was well hosted without disturbance. On the top of the structure, the plant would also digest the colony’s old beeswax and propolis into a single wax-coated petal that waterproofed the structure and provided temperature insulation at the top of the structure.

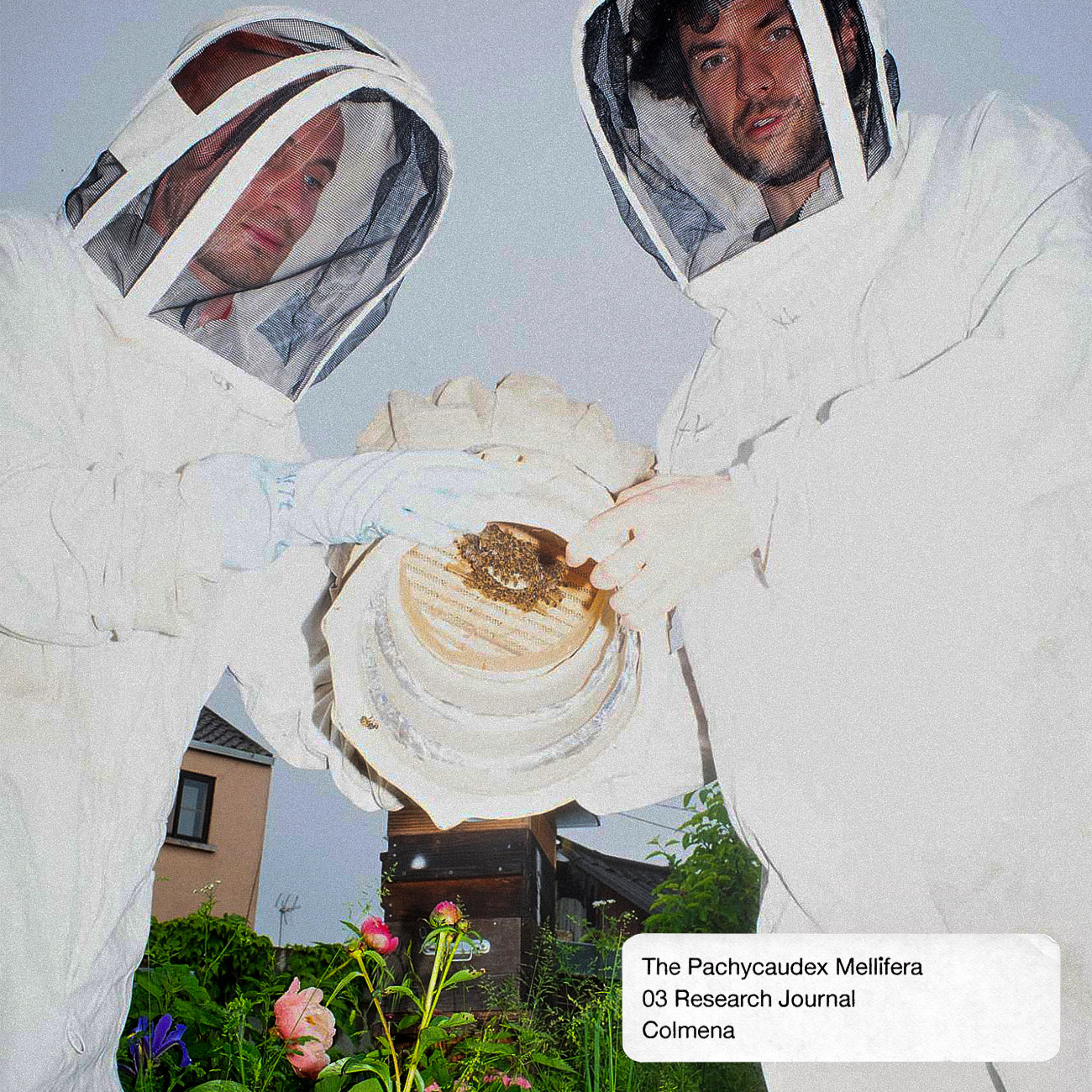

This type of evolutionary and speculative mindset brought us into an interesting design methodology where we were conceiving an agricultural tool as a living organism. Although it could seem stupid too, we were really into it. The hive was almost finished. We really wanted to test it, we were so convinced about it. So, Raphael made a couple of calls and he found a buddhist beekeeper on our street. You should’ve seen his face when we explained to the beekeeper the project with our excitement and my broken french:

“The Pachycaudex mellifera is originally a shoreline plant that adapted to dry environments by developing a water reservoir in its thick stem. Over time, its hollow caudex became an ideal receptacle for bee colonies. The species has since then evolved to partially absorb the honey produced by its bee guests, and digest other substances like the wax into a coated single petal. On its top, the plant produces a glucose-based poison to attract honey bee predators. Here the individual is in its juvenile stage, which can be distinguished by its small size and its immature exterior appearance.”

Khagan, the beekeeper looked at us like we were two stoners. “What have you been smoking, guys?”, he said right away. We looked at each other and started laughing. After this funny intro, we delved into the practicalities of the beehive. I noticed right away he was an ecological beekeeper by the kind of questions he asked. “How does the colony grow in this hive? Where do you remove the honey from? Why ceramic? Do you leave the colony an empty space on the top or on the bottom?”

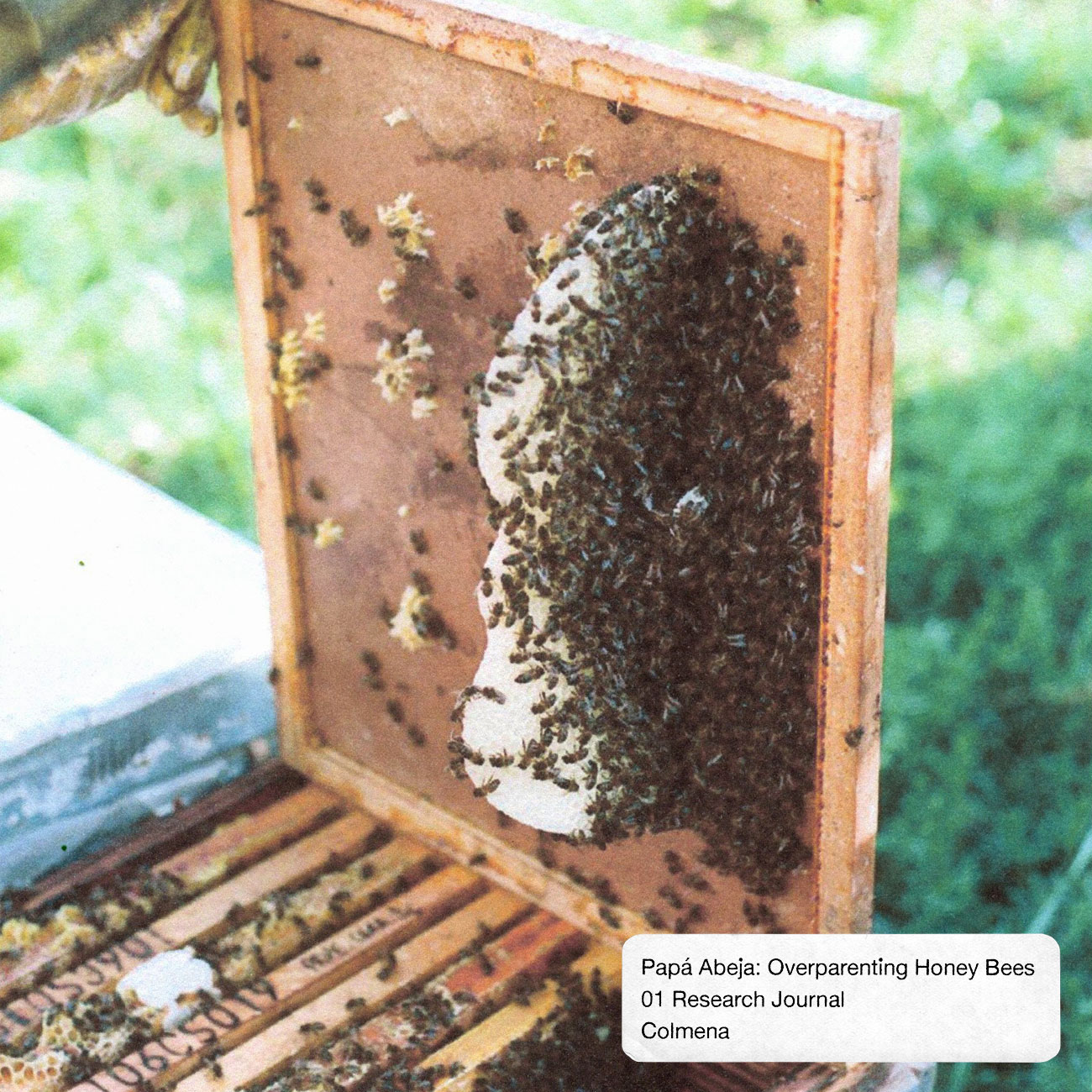

At the time, we conceived the hive based on the principles laid out by Oscar Perone, the founder of a beekeeping style that he named PermApiculture, based on the ethical principles of permaculture. Like other ecological beekeepers, he proposed a beehive where you only open it to harvest. Easy until here. He proposes a vertical hive composed of modular floors, where the bottom half is left for the nest and honey reserves, a sacred space for the honey bees that the beekeeper never touches. Then there are a series of top floors, “the beekeeping area”, where the beekeepers adds empty modules and rub them full of honey and wax. In our hive, we decided to clearly differentiate the nest and the beekeeper parts through material choice. We built the colony area in ceramic, and the honey modules with bamboo steamers.

To answer our questions, Khagan invited us to one of his ecological beekeeping courses. First, he told us ceramic had a very low thermal coefficient, meaning the bees would be cold in winter and hot in summer. Bravo, Raph and Pablo, brilliant material choice. Second, he asked how we planned to cultivate and harvest the honey, and we explained that we would through the empty bamboo steamers on top. He found it interesting, although explained to us a climate concept I will never forget: the isolated honey.

Over centuries humans have tested ways to cultivate honey and developed the honey supper concept, which is basically adding empty space to the top of a bee colony. Honey bees never have empty space on the top of their colonies as they always grow hanging downwards. When they have this empty space, they produce honey storage very quickly, not because they need it, but because they need isolated materials for climate stability. This honey produced is of very low quality, as it’s placed in freshly made cells that haven’t been propolized1 as much as cells that have kept a lot of larvae in the past. When we add honey suppers on the top of a colony, we extract honey with less medicinal properties.

- 1Propolis is the sanitizing material bees use to keep the hive out of bacteria, and it contaminates the honey, adding lots of beneficial properties for health.

To sum up, Khagan made us understand that in beekeeping everything “depends”. There are no rules and every decision is informed by specific contexts and conditions. In our case, ceramics were not the best thermal material for a cold humid climate like Paris, neither was bamboo. Our beehive could have worked well in a temperate climate closer to the equator. Anyway, our buddhist beekeeping master managed to place a tiny swarm in the hive, which immediately began producing beeswax combs.

Pablo Bolumar Plata is a designer and researcher focused on the transformation of material environments. His ongoing research in the apiaries analyzes the relationship between bee colonies and humans through spatial design, aiming to expand bee cultures beyond honey production.

- 1Propolis is the sanitizing material bees use to keep the hive out of bacteria, and it contaminates the honey, adding lots of beneficial properties for health.