Profiling systems bridging the urban, the periurban, and the rural to complicate our understanding of the geography of our cities.

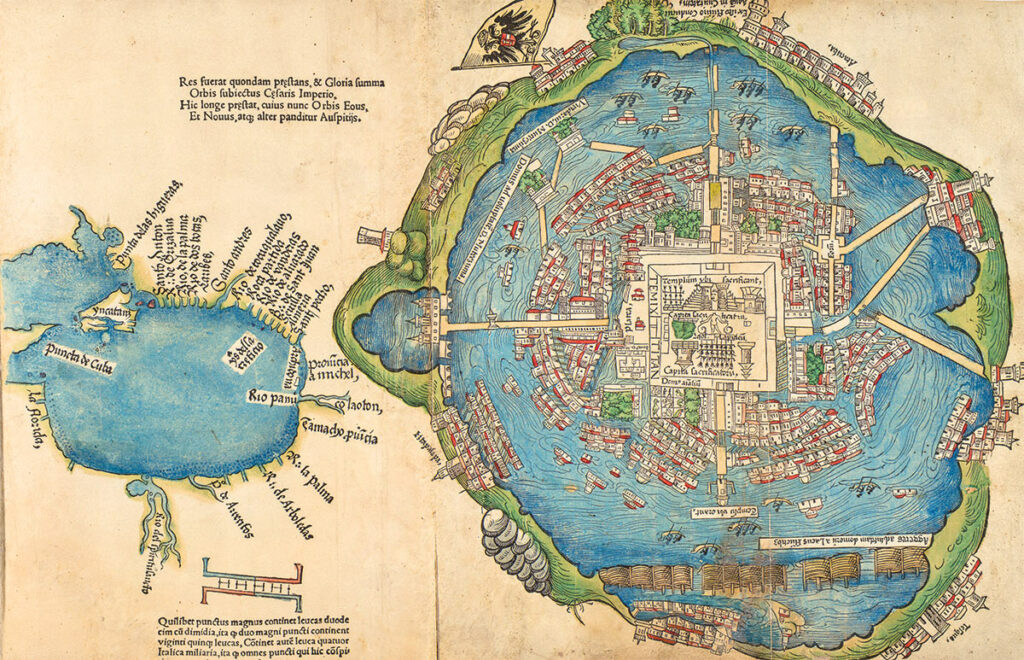

Next morning, we came to a broad causeway and continued our march towards Iztapalapa. And when we saw all those cities and villages built in the water, and other great towns on dry land, and that straight and level causeway leading to Mexico, we were astounded. It was all so wonderful that I do not know how to describe this first glimpse of things never heard of, seen or dreamed of before…large canoes could come into the garden from the lake through a channel they had cut, and their crews did not have to disembark. Everything was shining with lime and decorated with different kinds of stonework and paintings which were a marvel to gaze on…But today all that I then saw is overthrown and destroyed; nothing is left standing.

Bernal Diaz del Castillo

Reading descriptions by Bernal Diaz del Castillo, a conquistador in Cortés’ army who participated in the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlán and later documented his experiences1, it is impossible not to long for a glimpse of this dreamlike world that rivaled ancient Rome and Constantinople– and to mourn its destruction. Chasing this glimpse is, in part, the work of Ana María Durán Calisto’s Yale School of Architecture research course “Territorial Cities of Pre Columbian America.” Over the course of this semester, my classmates and I are attempting to visualize our research on one Native American city, leveraging our skills as designers to produce maps, plans, and diagrams.

Durán Calisto is an architect by trade, and her work centers around the history of urbanization in the Amazon basin. The intention of the seminar is to both build a more robust architectural accounting of pre-colonial urbanism in the Americas and for design students to learn from these urban ecologies as we seek to reestablish a sustainable relationship between human settlement and environment.

As I investigate rural-urban systems for MOLD over the coming months, a conversation with Durán Calisto about these profound (and prescient) American cities seemed like a fitting place to start. Below is our conversation, edited for length and clarity, in which we discuss her work, the course, and the design ingenuity within indigenous cities of the Americas.

- 1. Diaz del Castillo wrote his account, “Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España” in the late 1500s as an old man, many years after the fall of Tenochtitlán.

Ben Derlan:

In this 6 part series, I am attempting to trace the systems which connect our cities to the hinterland, urban to rural. I feel this tie is captured in the title of the class “territorial cities.” How do you understand the territory in relation to the city?

Ana María Durán Calisto:

The relationship between the city and its hinterland is absolutely fundamental; there’s no city without the hinterland. To see what has happened with globalization is very disturbing. The natural relationship, if you wish, between the city and the hinterland that feeds it, that provides water, that provides fresh air, that provides so many resources for the well-being of the city has been disrupted. What happens now is that the hinterland of our cities is an ocean away, kilometers away, it is disjointed from the city. How can you take care of an American city’s hinterland if it’s in Indonesia, or the Amazon? It is very difficult. So that is one of the outcomes of globalization we are really going to have to tackle. How can you take care of that hinterland that is taking care of you?

BD:

In our course, we’ve spent the first few weeks studying the ontology of the city– how do we define a city. Perhaps to reaffirm that these pre-columbian cities were in fact, cities. Where does this doubt come from?

AMDC:

There’s always this doubt, which I have found fascinating because I have encountered it over and over again. Why is it that for the western ontology of the urban, these cities somehow don’t fully qualify, don’t fully fit the definition and expectations of what a city should be? That’s why we’re investigating (in class) how the west has defined terms like urbs, civitas, polis, communitas, and questioning the narrative of evolutionary, linear urban formation that we inherited from the Enlightenment and social darwinism. An assumption which, in a way, stagnated archeology in places like Amazonia for decades.

The prevailing narrative, since V.G. Childe, an archeologist writing in the early 1900s, stated that intensive agriculture precedes the emergence of cities2. In Amazonia soils are very poor and very acidic. So Betty Meggers and the other archeologists first studying the region believed, if soils here are very poor, and incapable of supporting intensive agriculture, cities couldn’t have existed in the region3. But this condition was based on a specific understanding of agriculture in the European or Mesopotamian style, not in terms of forest agriculture, polyculture or agro-ecological forest: the multi-species, highly biodiverse agricultural systems of Amazonia. So Amazonia has been sunken underneath all sorts of preconceptions about what agriculture is and how it looks and what urbanism is and how it looks. The widespread existence of terra preta and terra morena, fertile and anthropogenic soils, brought this hypothesis under scrutiny.

An important Amazonian archaeologist we spoke with last semester for this course, Clark Erickson, told us that “wherever you start carving the ground in Amazonia, you find ceramic shards.” It makes you wonder about the myth of the “pristine forest”4. He said that he still has yet to find it, because every site he had visited personally had delivered some sign of human occupation.

- 2. Childe, V. G. (1950). The urban revolution. The town planning review, 21(1), 3-17.

- 3. Betty, M. (1971). Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Chicago.

- 4. Denevan, W. M. (1992). The pristine myth: the landscape of the Americas in 1492. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 82(3), 369-385.

BD:

It is truly shocking to me that an urban network existed in the Amazon. We know so little about these forest cities. How was it that this knowledge has been lost?

AMDC:

Native American knowledge has unfortunately been placed [almost in its entirety] under the umbrella of anthropology and its many branches. The west has had this difficult relationship with America, a place that was not mentioned by the Bible nor classic authors. From very early on, native knowledge was exported back to Europe in the form of reports. I should note that this is not a phenomenon of the 18th or 19th century, it does not start with the La Condamines or the Humbolts of the world of science but in the 16th century with the Spaniards and their thorough chroniclers, and the hybrid codices. Doctor Diego Álvarez Chanca, who accompanied Columbus in his second voyage, was the first European to write reports on medicinal plants, the biology and zoology of the Caribbean, even the dual stance towards the “Indians:” they were simultaneously described as the “natural man” (Rousseau’s “noble savage”)5 and the brutal savage, the cannibal, the perpetrator of human sacrifice (traits that would be used to legitimize the conquest and its brutality). Voyagers started incorporating indigenous knowledge into European epistemologies early on, eventually categorizing it into the taxonomies of existing sciences (medicinal, biological, etc.) and creating a silo specifically focused on casting the inhabitants of the Americas as the object of study: anthropology and its branches. Indigenous science –and it is a science, highly empirical– is incorporated in European science, but not acknowledged as such, nor acknowledged as one of its sources.

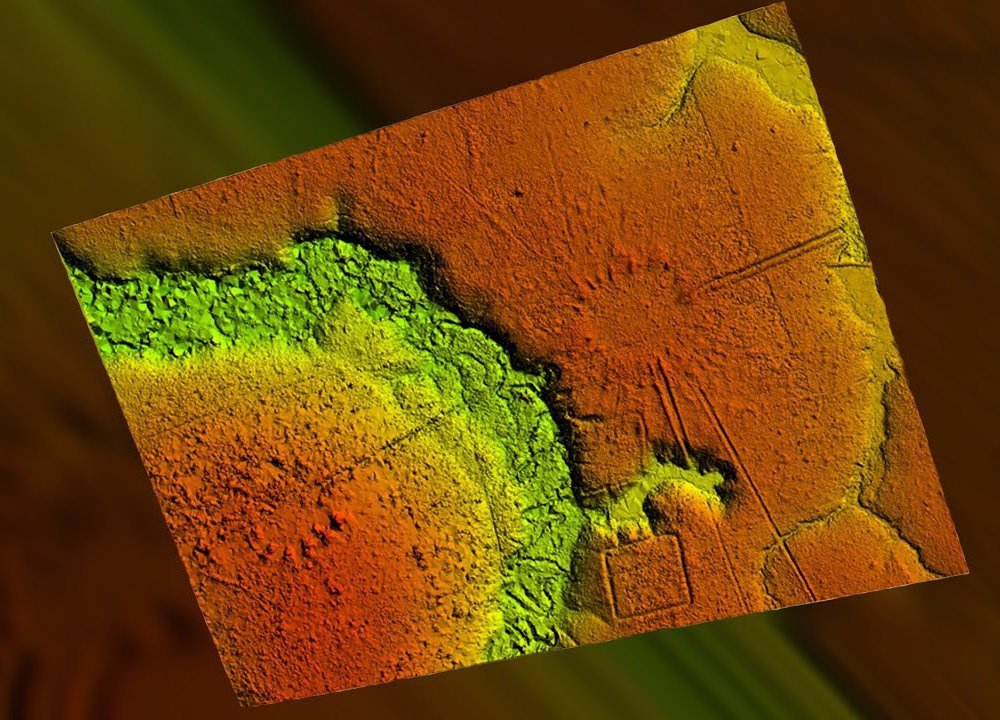

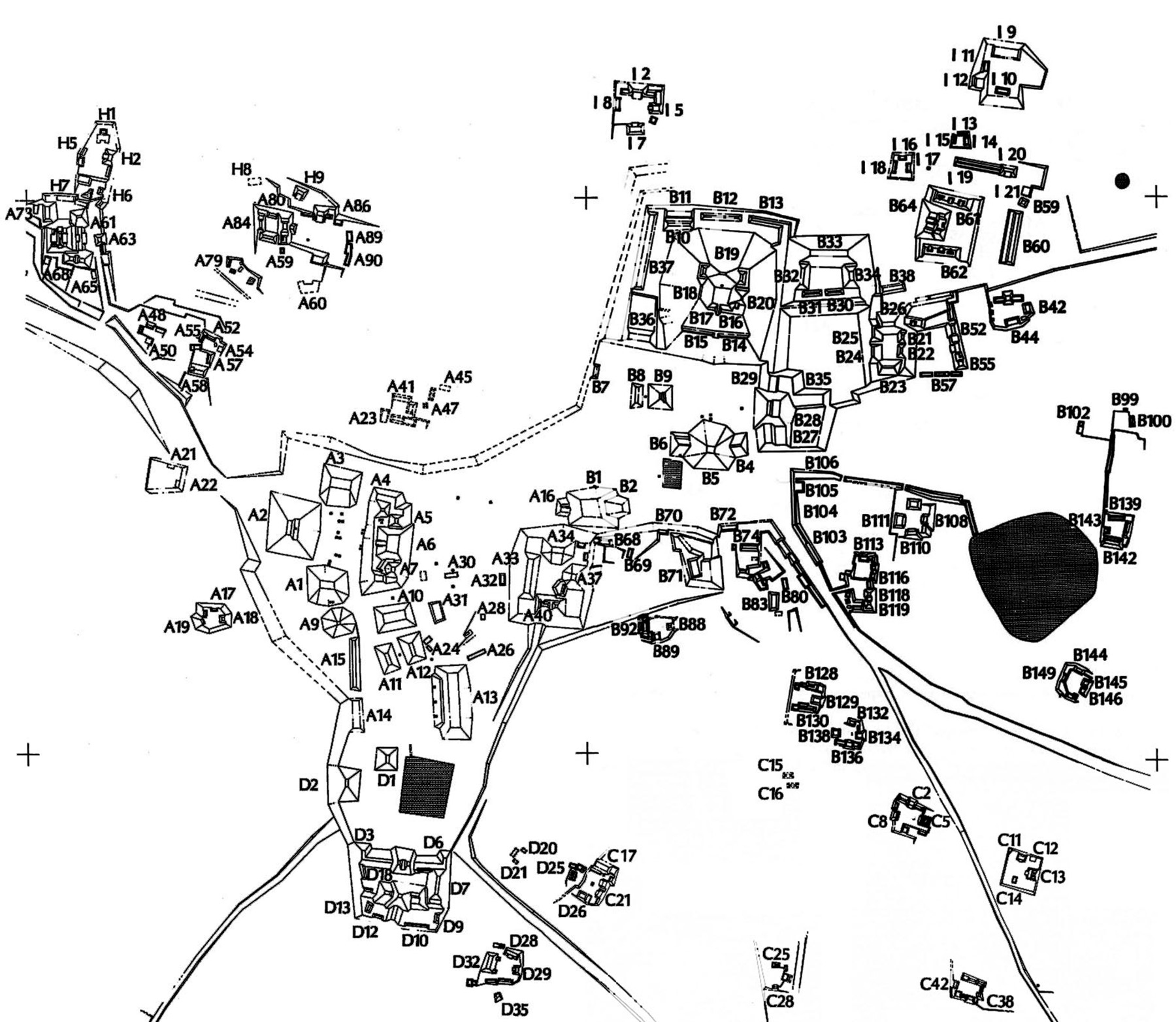

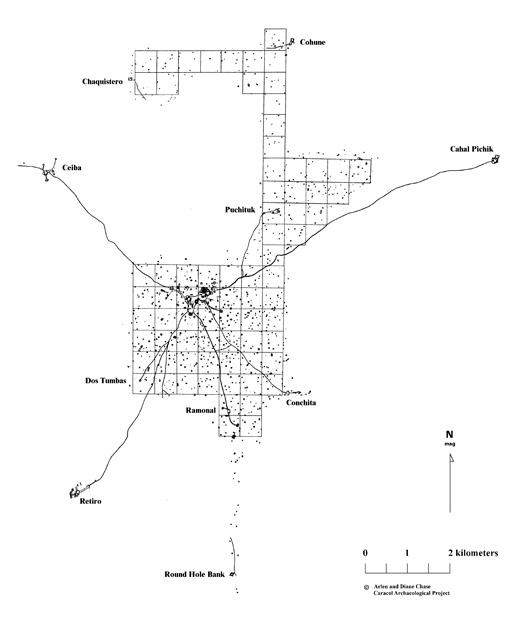

At the same time, the modern study and understanding of indigenous towns has been halted by prejudice. At Caracol, in Belize, archeologists had focused their work on the civic center: the monumental temples, the plazas, the administrative and residential precincts. As such, Caracol, like other Maya cities, was described as “a ceremonial center,” not a city. But the archaeologists were not seeing the whole picture. When LiDAR satellite imagery emerged, American archaeologists Diane Zaino Chase and Arlen Chase started applying the technology to their research and they uncovered the whole constellation6.

- 5. The writings of Bartolomé de las Casas must have also profoundly influenced Rousseau´s construction of the “noble savage.”

- 6. Chase, D. Z., & Chase, A. F. (2017). Caracol, Belize, and changing perceptions of ancient Maya society. Journal of Archaeological Research, 25(3), 185-249.

BD:

In this course, and in your upcoming book, we are trying to unite a diverse range of cultures and city-states, from Cahokia in present day Illinois, to Tiwanaku, in Bolivia, under this term “territorial cities.” I wonder if you could talk about what unites them?

AMDC:

Because the American world developed in relative isolation, and I mean relative because we know of earlier European and non-european contacts, it developed its own socio ecological systems. There is really an “American Exceptionalism:” one that is deep and ancestral. The Americas, in terms of developing urban ecologies, were incredibly advanced.

What is amazing about Amazonian urbanisms, and other Amerindian territorial cities, is the line between built environment and environment blurs– Amazonians designed and built productive forests, a diverse array of what Shuar architect Fernando Huambutzereque calls “micro-ecologies,” highly productive and collectively managed, highly diverse socioecologies. These are built environments, but they are working with biological materials such as trees, soils and root systems. They are incredibly complex cultural habitats that from our western perspective we would consider “the environment.”

In the documents of the 16th century, over and over again the colonial priests or missionaries complain that the native americans are “claustrophobic.” They can’t get them to come into the church, they hate being inside. These are outdoor people. Perhaps that’s why they had gigantic plazas, of scales Europe had not seen. The largest plaza in Europe was tiny compared with those in Tenochtitlan or Cusco. These large, open public spaces were not just about civic life– the plazas of the native americans are always related to astronomical elements, geographic features, sacred components of the topography, the hydrological system.

They tend to have axes that are just mind-boggling in terms of the geography. You will experience it when you walk, for example, to Machu Picchu. The visual axis is geographical in scale, it is beyond metropolitan. Take, say, a baroque axis in Paris– the Avenue des Champs-Élysées which takes you all the way to the Arc de Triomphe. In Cusco, that would take you all the way to an Andean peak, or a star. It is another scale entirely. You feel that very strongly in the Andes. The scale in the Americas was beyond belief.

BD:

How does this scale factor into the arrangement of food production in the city?

AMDC:

I am convinced that Native American cities are built from the ground up. Take Tenochtitlan: the domestic agricultural unit of that city is an extended family that lives in multiple households within an area of chinampas, which they manage and construct through collective work, sometimes in association with other residential units, through reciprocal exchange. Tenochtitlan displays centralized power. Households are probably paying a percentage of their produce in tribute, keeping some for sustenance, and exchanging the rest in the grand markets of the city. You have a system of land management founded on extended families managing their commons. They have the right of use, but the land belongs to no one. It’s not private property nor the property of the lord.

In Mayan cities you see the same substructure, analogous agro-ecological systems based on collective design, construction and management of the land. In the case of Caracol, each one of the domestic ecological units is managing an area of terraced milpa and/or agroforestry. Each extended family manages a micro agroecology. The system is additive, and can scale up and generate centralization as some groups acquire an always unstable supremacy over others. Each domestic unit builds on its sustenance economy, but also exchanges surplus and specialized crafts with other groups.

These territorial cities can not be described in binary terms: they are open, yet closed, interconnected but isolated, inter-dependent and autonomous, rural and urban, hierarchical and horizontal, and its citizens are peasants. In them, one can hunt, gather, cultivate, develop a specialized activity or function; the paleolithic, neolithic, and urban revolution coexist in a non-linear time.

BD:

Can you expand on that ambiguity? How don’t these cities fit within our western framework?

AMDC:

Let’s look at Tenochtitlan, a city that is acknowledged by the west as a city because it has the kind of central state that we look for and clear statecraft. It displays monumental architecture, which speaks of a social hierarchy, which in turn speaks of specialization, division of labor, wealth accumulation. This is recognizable, this is closer to a city in Mesopotamia or the Mediterranean.

But there is something about it that does not fully match our definition of city. You don’t have this stark division between an internal nucleus that is densely populated and an external agricultural area and hinterlands beyond. Think about all the binaries that break down in this city: is it open or is it closed? It is open and closed at the same time. Is it urban or is it rural? It’s both. Are these citizens or farmers? They’re both. Centralized or decentralized? Both. I love these cities because they break down all our binaries, and that’s why we need to look at them.

BD:

What can designers learn from studying these cities?

AMDC:

This is a way of making the built environment which is extremely brilliant in its ecological understanding of a place. These were builders of ecologies. Their built environment is really an environment. The new generation, I hope, is going to integrate these cities into the larger urban knowledge. With most urban history books, the pre-Columbian chapter is not there. And it should be.