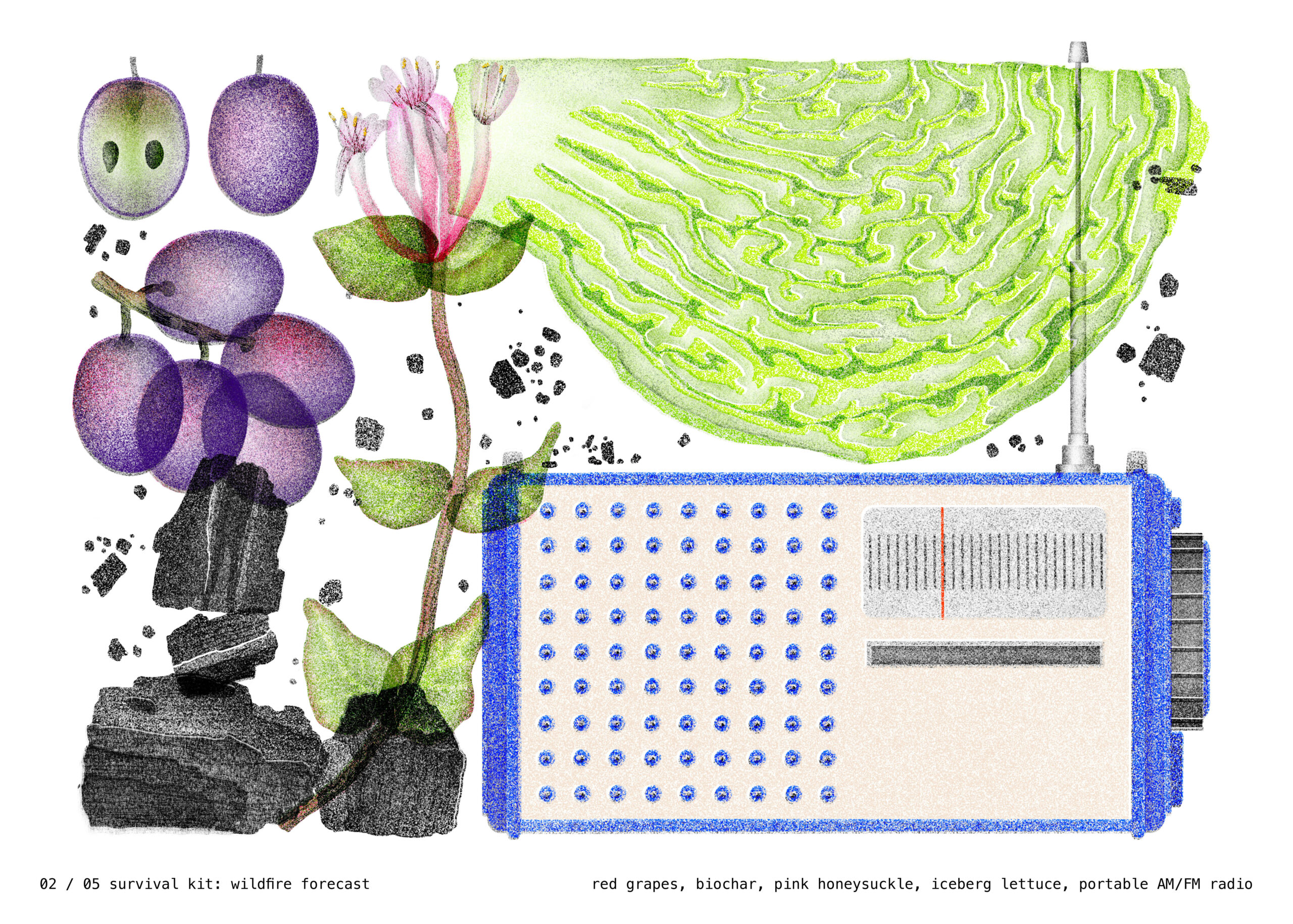

The piece is part of Food Forecast, a series that offers a glimpse into the way our shifting climate will impact our future diets.

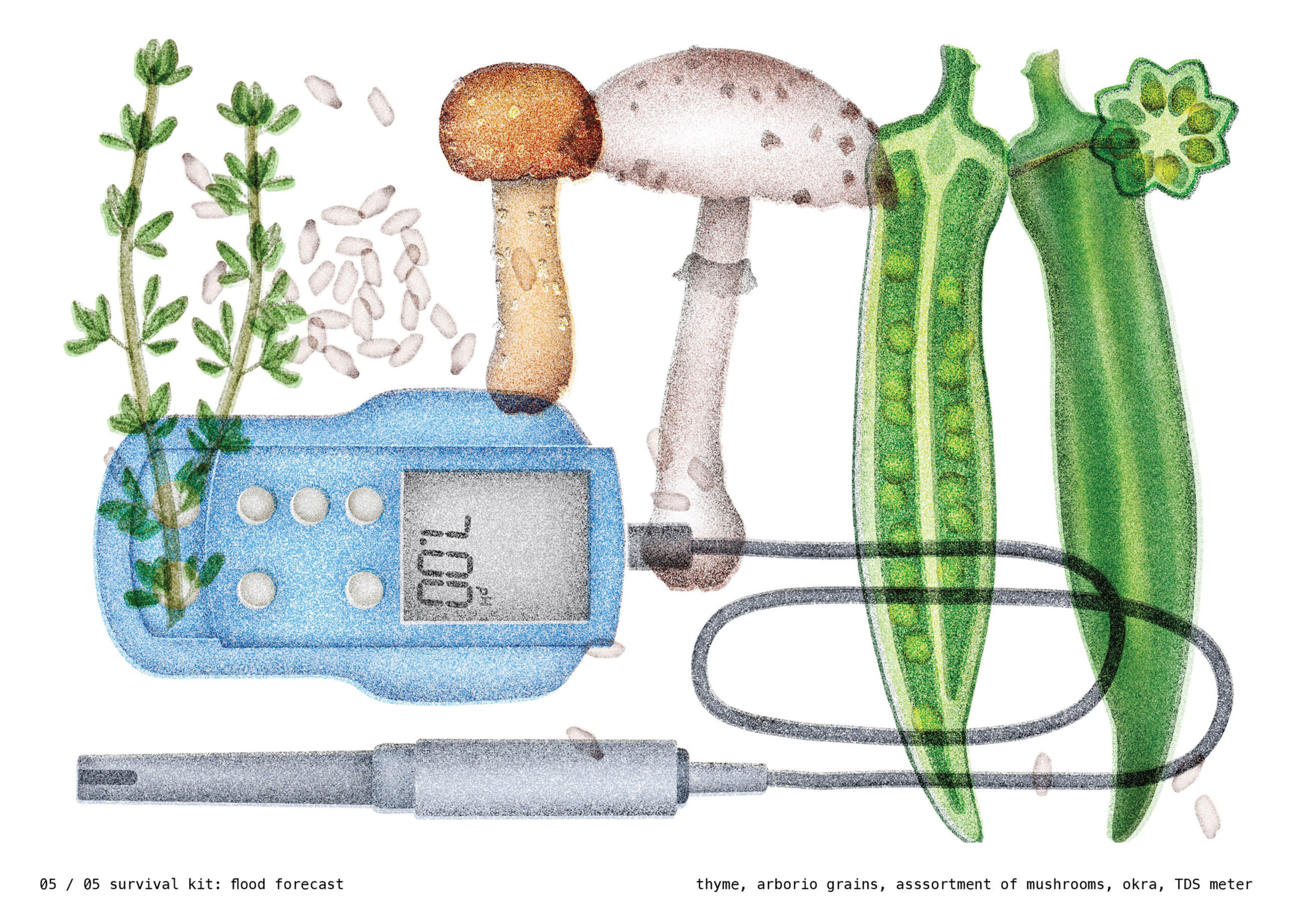

I recently learned about a farming technique that reads like a dream: floating gardens on rafts made of woven hyacinth plants up to 200 feet long, gliding over glossy water and steered by farmers with wooden oars. Okra, cucumber and amaranth seeds are embedded into small balls constructed of local aquatic plants, and nestled into the organic structures where they are cultivated by farmers until maturity. Called baira or dhaps, these crop islands were developed by farmers in Bangladesh to sustain agriculture during the flooding typical of their 8-month long monsoon seasons. The structures rise and drift above the water buoyed upwards by the buildup of heavy rain. Annual floods, monsoons or rainy seasons, are as old as human records. In response, countless designs have emerged to sustain agriculture in these drenched lands. Among them are the intricate stepwells of India that hold monsoon rains in ornate architectures, or the terraced rice patties across southeast Asia that often host fish alongside the grains.

However, beyond rainy seasons, floods are rising in places they never did before and with more frequency. Hot air holds more moisture, and with rising temperatures, that means more rain and unusual weather patterns. Paved with impermeable concrete and asphalt, our cities are grossly unprepared, behaving like giant empty swimming pools easily filled by just inches of rain. It would only take 2 inches of water for the NY subway to stop working, which happened during Hurricane Sandy. Outside of cities, when this rain falls heavy on dry land, the land can’t soak it up quickly enough and leads to flash floods.

Measuring rain droplets in inches inadequately communicates the massive scale of recent global floods. Sudden and unexpected, in just the past few months over 31 inches of torrential rain poured down on North Carolina, 20 inches in Valencia, 19.7 inches in Thailand and heavy rain is currently falling in California and Northeastern Australia. It’s hard to visualize what these numbers mean, until you see a picture of a neighborhood underwater, or entire orchards turned into lakes. A flood’s presence lingers far after the water has drained.

This has led farmers and food providers to imagine new ways of collaborating with one another and with the water by preparing croplands and what is planted there. While there are many tools and ancient strategies that could be employed, if you don’t own your land and the first responders are the government or National Guard, prepping is not straightforward.

The way a flood arrives quickly but recedes slowly necessitates collaboration. In Valencia, after last November’s floods, hectares of farmland were submerged. With treetops barely bobbing above the surface of floodwaters, two-thirds of Spain’s mandarin, persimmon, and almond crops for the season were drowned. In response, thousands of people from across Spain brought their tractors, trucks, shovels, buckets, and brooms to help their neighbors alleviate the pressures of the water. Many blame the government for not adequately preparing residents. As it becomes more widely accepted that the 100-year flood is an antiquated notion, farmers across the world are trying to keep up.

When I talked to Seth Mose he was on his way back home after cleaning up the damage from a flood at the Vermont dairy farm he runs with his wife, Monika. The rain had fallen quickly and ruined vital hay for the cows’ meals. A first-generation farmer on leased land, Seth told me that he’s learned that, “Floodings [are] inevitable, it’s the world we live in now, and as farmers, you just have to really enjoy doing it… and realize that you can’t control everything.” For a dairy farmer, flooding brings in a whole host of concerns: floods can damage cows’ hooves, standing water allows for the breeding of biting insects and muddy, soft ground means that the cows have to stay indoors so that they don’t crush the grass with their body weight. “All our decision-making is based on the quality of [the cows’] lives. If we have happy cows, we have good milk to sell and drink,” said Seth. He emphasized that with floods occurring year-round it’s a constant dance. He told me ideally, in anticipation of future flooding, he would raise the hay and buffer their barn as well as create some drainage lanes. I personally imagined some little cow boots to protect the cow’s tender hooves.

A few miles away in Upstate New York, Choy Division, a no-spray farm specializing in East Asian heritage crops such as head mustard and napa cabbage, is no stranger to floods. Three years ago a hurricane hit the region mid-September, wiping out crops like tomatoes and eggplant, essentially washing away days of labor alongside the vital produce. Choy Division leases land in the historic Black Dirt Region, an area known for especially fertile soil that developed at the bottom of an ancient glacial lake that was itself formed through years of flooding. Although the marshlands of this region were drained in the 1880s, the land retains memory of its past life. Choy Division founder, Christina Chan told me, “Black Dirt is always in some sense trying to return to being a wetland.”

Knowing this, Choy Division has installed drainage tile under the fields, and a semi-functional water pump. But, even with these technologies, lower-lying farms can get turned into lakes. After the floods, there was a land grab for less flood-prone farms and an overall effort from farmers in the region to diversify crops. On the other hand, weather is unpredictable and this year the farm experienced drought. “I have to do a little bit of everything to end with some level of success,” Christina said. While she is now building some raised beds to be more flood-resistant, the farm’s most effective form of resilience comes from their surrounding community of fellow farmers. When the floods came, neighboring farms gifted them vegetables to account for their losses, and they do the same when there are sudden frosts or other unforeseen climate events.

“Before the storm, Asheville was considered a climate haven,” Silver Iocovozzi, owner of Neng Jr.’s, a small Filipino restaurant in Asheville, North Carolina, told me. Then, there was Hurricane Helene. Sweeping through an area that had already sustained heavy rain two days prior, the torrential downpour brought on by the storm overwhelmed the city’s infrastructure. Within hours, Asheville’s entire infrastructure was shut down. It was so sudden, that there wasn’t even an evacuation notice for residents to respond to. The systems in place to respond—FEMA and the National Guard—were either incompetent, mismanaged, or outdated. To this day, residents have only received $750 dollars from FEMA. During our conversation, Silver emphasized that Asheville is not an island, and that aid could have been brought in much sooner. However, instead of waiting, Silver and his husband, Cherry, immediately filled in the gaps by getting to work feeding people. “As restaurant people, chefs, and service workers [we] know how to anticipate people’s needs,” Silver said.

Although there was no electricity or running water, together with friends they collected food donations and cooked hot meals for people in need affected by the hurricane. Uniquely positioned to be of service feeding people, and moved by the galvanizing of community support, this experience has changed Silver, altering their outlook on the future. Croplands were drowned and water systems remain extremely contaminated. “I don’t think being a prepper is a bad idea at this point,” Silver admitted, “I’m thinking of ways of how I can conserve water at this point because water is going to be one of the main things we fight over in the future of climate change.”

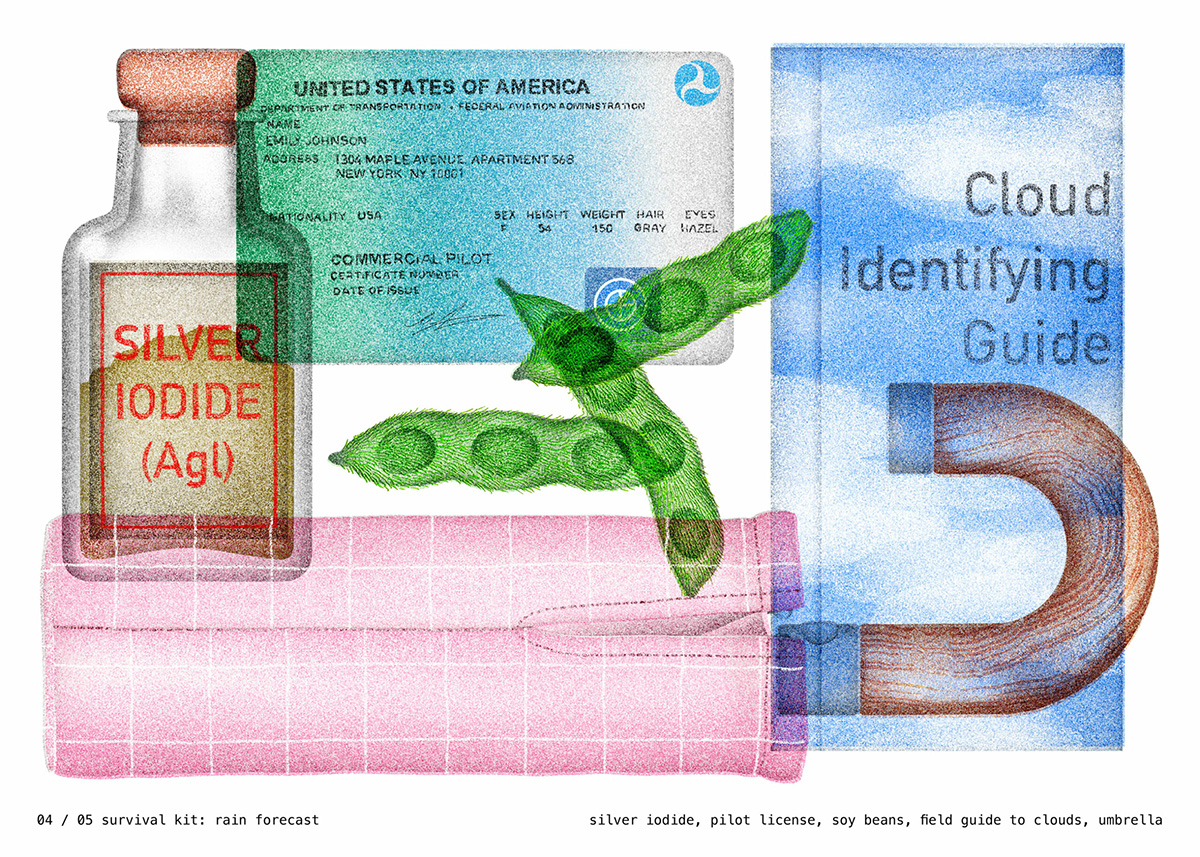

While writing this piece, I kept asking myself how I could talk about flood in a way that isn’t depressing, that doesn’t pull us underwater too. But perhaps, it’s important to feel the weight of our reality as well. We will fight over water. We already do. However, there are also new ways of existence that we can adopt to adapt to our new relationship with water. In China, Kongjian Yu popularized the idea of Sponge Cities, porous soft-scaping that would allow stormwater to seep back into the ground and replenish natural aquifers rather than building up on hard surfaces. Studio De Urbinisten in Rotterdam is building “water squares,” areas that double as a public space and a pool to gather stormwater runoff.

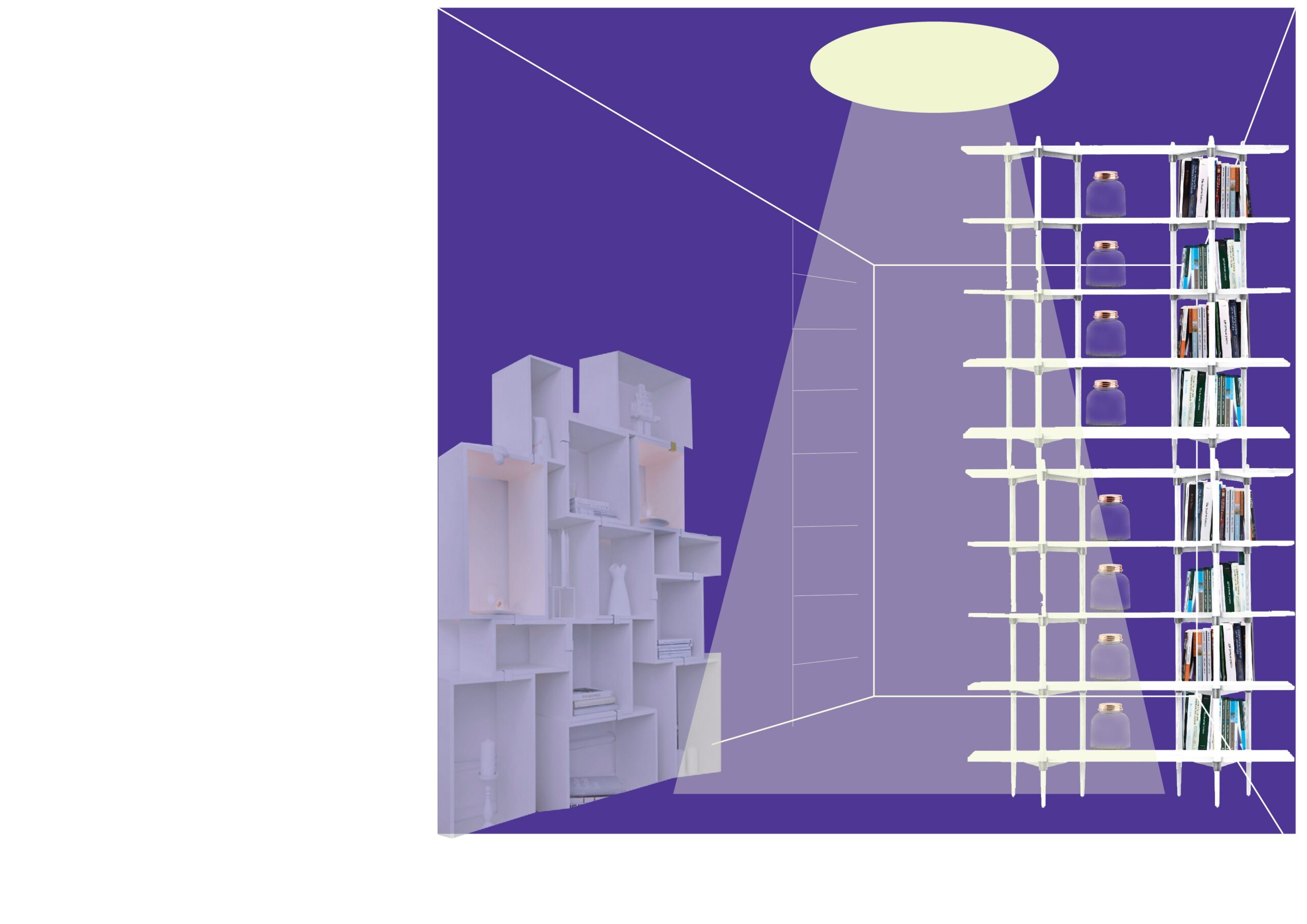

A few years ago as a member of New Inc’s Ideas Cities in New Orleans, I imagined a system of knowledge exchange where people were linked not by their geographical borders, but by their climate zone. This included new identification cards and a material and tool library where each floor was a different altitude above or below sea level rise. I pictured this library on a boat, floating along coastlines gathering and sharing methods of coping with our climate realities. I see a future of interglobal solidarity, where people share their techniques for managing floods with people across the world who have been in the same circumstances.

I predict we will start to recognize the importance of autonomous and decentralized water infrastructures that don’t rely on the government or private interest groups. I predict floating gardens, suspended gardens, rain gardens, and raised bed gardens that float. I predict little rain boots for cows and umbrellas for leafy greens. I predict mutual aid will continue to be more effective than governmental.There are endless methods to working with floods and very little risk of overpreparing but it will require resources and new methods of collaboration.