This story is part of our editorial series, Work in Progress on design and restaurant labor.

There’s an irony in how inhospitable the hospitality industry can be to people with different abilities. From the lack of accommodation for disabled diners to the extreme constraints of professional kitchens, for those with differing abilities, the hospitality industry continues to perpetuate a cycle of exclusion. Breaking out of this cycle takes creativity and drive, qualities found simmering at the back of a Canadian food truck with a young man behind the wheel.

Aleem Syed grew up in the suburbs around Toronto navigating cold winters, hot summers and perpetually driving up and down highway 401. In the soft valleys and bold lines of this frigid city, Aleem’s parents, hailing from Hyderabad, India, used food to carve out a corner of community and belonging for their four kids. “I think food is the most important part of my family’s life. Everything is centered around food,” Aleem reflects. His parents would invite aunts, uncles, cousins, friends, even friends of friends over to share a meal. “Everyone would always say, ‘I love coming to your house. Your mom makes the best food,’” Aleem recounts. One day, a family friend asked his parents, as a favor, to cater his daughter’s wedding. “That was the first catering that we did. It was for a thousand people. Mom told me she didn’t know what to do. But she banged it out and it was perfect. And it just took off. From that day onwards, week after week, my parents were catering. They were doing these gatherings out of the garage in my house.” Everyone in the family pitched in and got their hands dirty, becoming intimately acquainted with the ins and outs of a hospitality business as well as the integrity behind a great meal. The fervor which Aleem watched unfold as his parent’s business went from an out-of-the-garage one time favor to opening Toronto’s beloved Taj Banquet Hall, sparked his drive to become a chef.

He took jobs in kitchens throughout highschool, attended the culinary institute of Le Cordon Bleu in Ottawa and worked successfully in fine dining at establishments such as New York’s BLT Prime and Toronto’s Canoe, Sopra Upper Lounge, Terra and Eagle’s Nest Golf Club.

The trajectory of his life and professional career changed in 2008 when he became paralyzed from the waist down. “I understand when I see people with disabilities, not just physical, but also other disabilities, such as cancer and ailments like that, it all funnels through the same brain in the same way,” Aleem recounts. “People still have that feeling of feeling bad. Then you feel bad for yourself. So you don’t want to be somewhere because you’re not up to par in your world.”

Very quickly, Aleem’s workspace became surreal and inaccessible to him. Yet his passion for cooking fuelled him to push the boundaries set for people with disabilities.

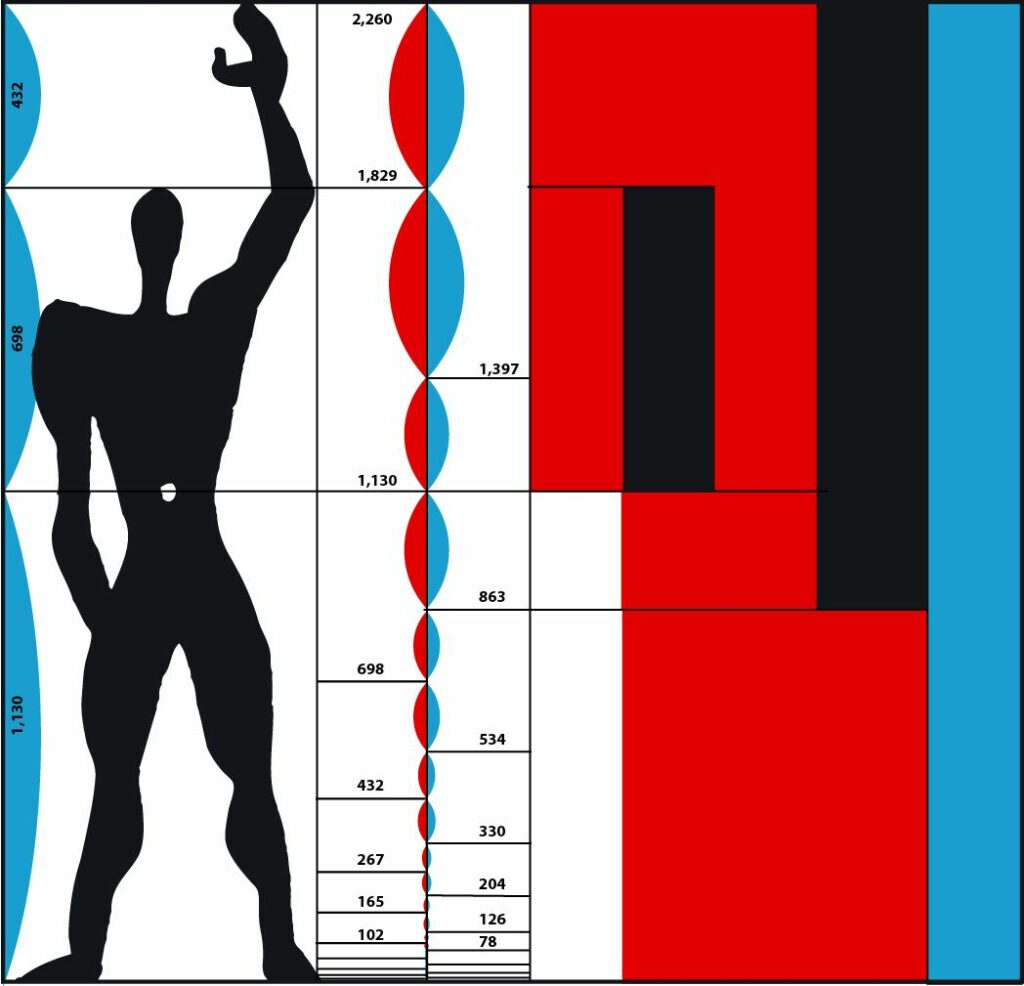

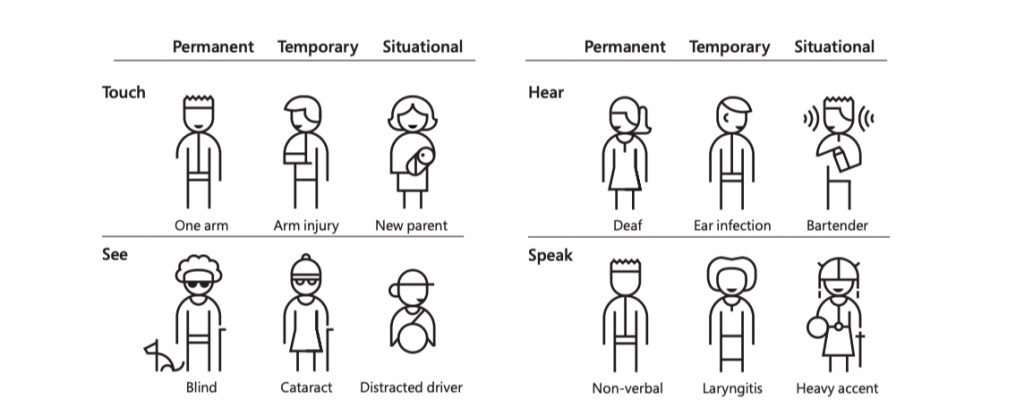

In a worldwide pandemic, this occurrence has become much more common. Especially within the hospitality industry which suffers from a longstanding aversion to inclusion. According to the World Bank, 15% of the global population suffers from a disability. Author Kat Holmes reframes this in her book Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design. “To put it another way, there are over 6.4 billion people who are temporarily able bodied.”1 She contextualizes this by explaining that as we age, we all gain and lose abilities. Abilities change through illness and injury, such as a broken arm or ongoing health problems from COVID-19. We’ve been sold an exclusionary myth of a “normal human being”.

- 1. Kat Holmes, Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design (2018), MIT Press

Kat Holmes breaks this myth down through an example of 1940s air jets designed by the US Air Force. After measuring thousands of bodies, fighter jets were designed to fit the average pilot. After experiencing a high rate of crashes which could not be attributed to mechanical failure or pilot error, a study conducted by Gilbert Daniels found that of four thousand pilots observed not one pilot fit all ten dimensions of the jet.

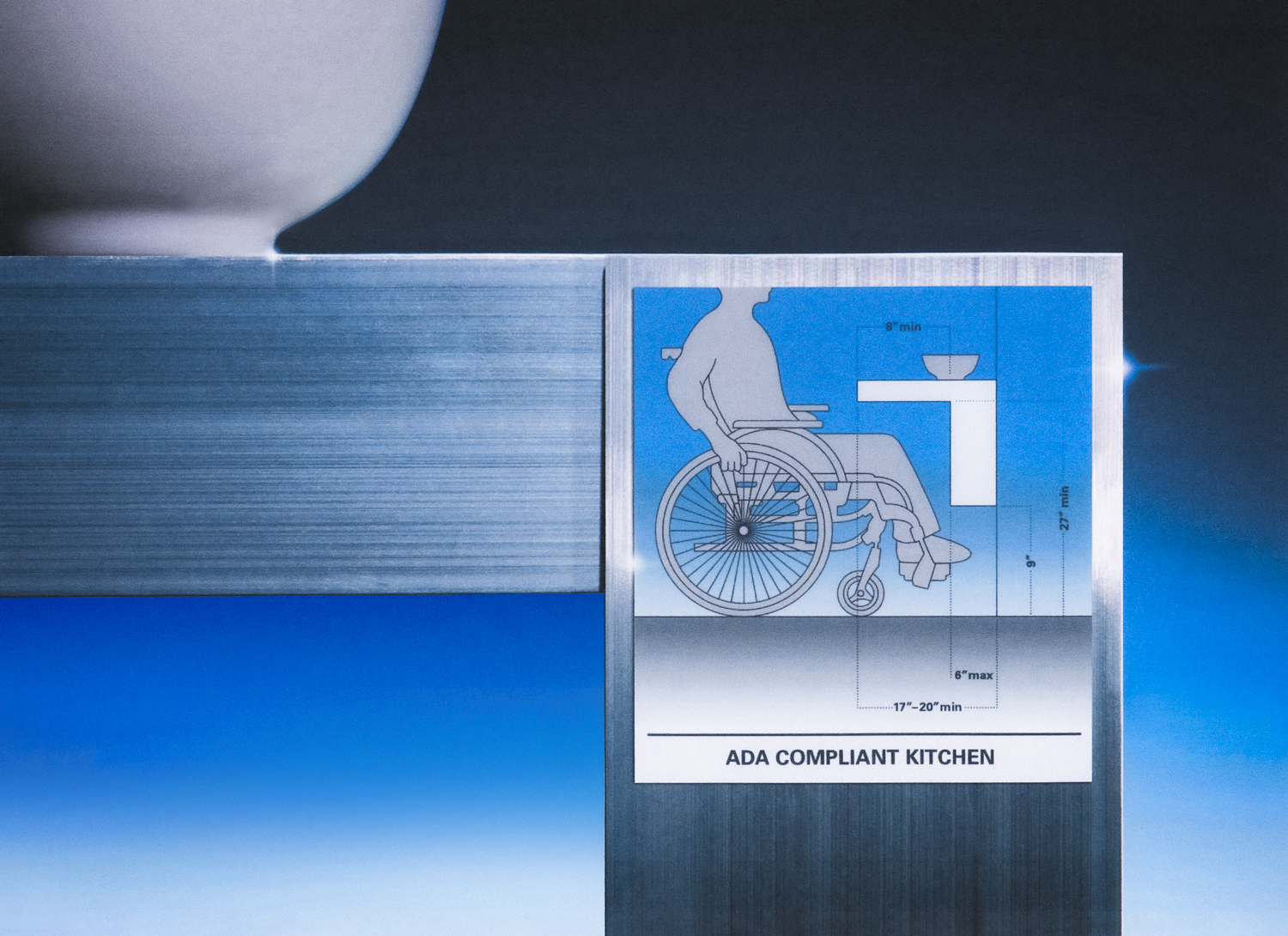

This led to the development of new design principles such as adjustable seats, belts and the positioning of controls. Understanding that all bodies are different allows us to better design our environments for the success of the collective rather than the expectations set on a single individual. This can be observed in the hospitality industry, more specifically the restaurant, its dining room and the kitchen. In the United States, an average commercial kitchen is around 1000 square feet. This size varies drastically depending on the number of patrons being served, type of operation and location of the establishment. Uniquely enough, the layout of a commercial kitchen, unlike any other commercial, institutional or public zoned space, is entirely up to the owner and operator of the restaurant. There are no ADA requirements and very little resource material on how to layout a kitchen beyond its culinary needs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) protects the rights of workers with disabilities and illnesses by stating reasonable accommodations must be made to an employee’s workplace or job duties to allow them to continue working, unless doing so would cause undue hardship to the employer. These accommodations must be decided and implemented through an interactive process between the employer and employee, which is often mediated by human resources for the sake of fairness. However, in the small and fast paced work environment of a commercial kitchen, there is rarely ever a human resources point of contact and the vacuum of inclusion is further widened through a rigid workplace ethic. In Mismatch, Holmes describes this process as the “cycle of exclusion,” where restaurant operators cite time limitations, an overwhelming workload and past precedents to layoff disabled staffers as the reason they cannot accommodate different abilities.

The hospitality industry’s lack of inclusion compromised its operations severely over the last few years due to the global pandemic insofar as more workers became disabled and in need of accommodations. Older workers who were otherwise healthy yet had preexisting conditions began needing accommodations such as working from home. Employees with pandemic related mental disabilities required accommodations too. These scenarios required sensitivity and interactive solutions-based design on behalf of employers which under the stress of the pandemic, were hardly ever met.

Interdependence allows designers to study human relationships and strengthen the way people bring their skills together to complement one another.

Kat Holmes, Mismatch

Holmes highlights our culture’s overemphasis on independence as a factor in limiting the success of a workplace in the hospitality industry which relies heavily on the wellbeing of the collective. People with disabilities often rely on assistive technology or human assistants to close the gaps in the implements of everyday life and a person’s abilities. In fact, all people are growing increasingly more dependent on technology. Interdependence allows designers to study human relationships and strengthen the way people bring their skills together to complement one another.

Aleem believes that disabled people would bring richness and quality to a workplace for this very reason, “Every person I came across with a disability pushed themselves so hard. There’s limitations to everybody. Limitations to what someone with a disability can and cannot do but trust the person to tell you their limitations. They will know when they need a rest or need to pull the plug. Being able to work in those situations is not easy but you can give someone with a spinal injury a six-hour shift instead of a twelve-hour shift. You can have multiple disable people instead of one abled person. The quality you are going to get on that shift will be worth it.”

When navigating life with different abilities, people are forced to consider their physical space in regards to their body in a more intimate and thorough way. This bodily awareness and sensitivity brings valuable insight and diversity to a work environment, especially one catered to serving others. However, people with disabilities are often considered liabilities and passed over for opportunities. Aleem believes this is due to a collective belief that disabled people are helpless and in need of assistance. This belief limits people with disabilities and minimizes their agency. “That’s the one thing that bothers me is that there are not that many people out there with disabilities working in the hospitality industry. A lot of these big establishments won’t give them any chances.”

Highlighting his experience when he became paralyzed, Aleem speaks on the lack of support from the government in helping people with disabilities take control of their lives.

“When I first became paralyzed, I had to go on the Ontario Disabilities Support Program (ODSP) for the first two years because my parent’s house needed to be wheelchair accessible and the only way you can apply for grants to have elevators, ramps or chair lifts installed is if you’re on ODSP. When I bought my food truck and my business started picking up, I was on TV for a cooking show and a case worker saw me. They contacted me to tell me they were upset about me being on ODSP and working, even though you are allowed to work while on the program. I was taken off ODSP and never allowed on again. It’s there for people but it didn’t make me feel good about my situation. You would just go there to pick up a check, there’s nothing else for people there.” Aleem’s story illustrates how government policy perpetuates the cycle of exclusion. He went on to say this lack of infrastructure is why people feel so helpless with their disabilities. “There are so many disabled people who are out there and they want to work but are unsure how and there’s no guidance or support for them.”

The lack of accessible infrastructure and accountability in the physical space of a restaurant begins in the kitchen and extends into the dining room. Restaurants are some of the least regulated spaces in terms of accessibility. Narrow passages, packed dining rooms, high table tops and eclectic multi-level layouts can almost never accommodate a wheelchair user. A rush to end plastic straws further limits disabled patrons. With such a difficult physical environment to navigate, diners can hardly look to restaurant staff due to the lack of accessibility training in order to accommodate disabled guests. These unanswered questions lead to disabled patrons, a sizable demographic with formidable buying power, to not engage and participate in culinary experiences in order to avoid unexpected disappointment, hardship and awkwardness.2

- 2. Baumann, Rachael Nicole, “Effect of Accessibility Information on Restaurant Selection of Consumers with Disabilities” (2014). Theses and Dissertations.

When learning of these discrepancies, both Aleem and Kat Holmes assert that people with disabilities aren’t looking for sympathy and don’t expect things to change overnight. There’s a general understanding that inaccessible layouts and environments are often due to limitations and constrictions. This is where people with different abilities would benefit from accessibility information. In Mismatch, Holmes redefines disability as not being a personal health condition, rather mismatched human interactions. This definition underscores the responsibility of the designer, whether it be the architect, host or chef, to make choices which either increase or decrease the mismatches between people and the world around them. Holmes writes, “It isn’t about needing help. It’s about making a personal connection. Guided learning is one way for people to understand why a solution works the way it does, which helps them feel more confident in their ability to utilize a solution.”

Programs such as Purple Table work to make disabled patrons more confident in engaging with the hospitality industry while simultaneously training workers to be adept at accommodating diners with different abilities and operators in creating a more inclusive workplace. If a disabled diner is considering eating out, a Purple Table certification will signal that accessibility information is available on how to enter, leave, sit and use the facilities including washrooms in the restaurant. This allows individuals to better plan their visit and not feel unprepared or worried about unknown limitations.

Where meaningful change can be made to allow for a more inclusive dining experience, the hospitality industry can design a more inclusive workplace in order to diversify their staff and encourage new talent. Aleem took part in this change when he pushed through rehabilitation after becoming paraplegic. Toronto’s first wheelchair bound chef, Pascal Ribeau, visited Aleem in the hospital and invited him to work at his restaurant Celestin for a night. That opportunity allowed for Aleem to prove to himself and those around him he was capable of not only being a valuable member of the kitchen, but an incredible chef. From there, Aleem moved on to handle the raw bar at Toronto’s Origin North. Working in fine dining confirmed Aleem’s passion for cooking was still intact and his skills had not deteriorated. He admits, “I had a really amazing life as a chef cooking for all these different places—in Toronto, in New York. There is a side of me that wishes I continued cooking for fine dining in my wheelchair. I did it for a little bit. But a part of me thinks I could have pushed the envelope further.” Aleem’s eyes were set on a different goal. He wanted to create his own space and cook on his own terms. “I decided, I don’t have the money for a restaurant right now and I wanted to start building myself. I had a really nice car that I sold and bought my food truck.”

With the launch of The Holy Grill, Chef Aleem became the owner and operator of Canada’s first wheelchair accessible food truck. Aleem made simple modifications to the truck which allowed him to maneuver inside and operate it independently. “The modifications I did on my truck was to put a back door in. I made sure I had more than thirty inches clearance—I have sixty inches inside the truck. That means I can do a turn at different points in the truck. Everything else like the counters are standard. But I also put in a wheelchair accessible ramp, so that’s why it is considered ‘Canada’s First Wheelchair Accessible Food Truck’.” He jokes, “But that doesn’t make the food taste better, honey.”

Rediscovering his work environment and designing a system which worked for him and his team is an ongoing journey. Aleem emphasized how fortunate he is to be able to make this a reality and how every obstacle encourages him to push further and focus on fulfilling his ambitions. “My work environment became surreal to me when I was sitting in this wheelchair in my kitchen in my food truck. Just being able to maneuver and not maneuver, how to pick this up or not, with no one’s help, was not easy. I purposely had to go through that for the first five years of opening the food truck. Call it ‘Trials and tribulations of opening a food truck when you’re paralyzed,’” he jokes. Aleem emphasizes how cooking is his purpose and The Holy Grill (THG) allowed him to pursue his passion. “My functionality is there, I’m capable of cooking up a storm in my food truck, but I had to alter a lot of different things in my life in order to do that. Every single day from the first day of service to the last day. I have to give it my all and go a little further than other people. For me it’s a physical and mental exercise.”

This focus is evident in Chef Aleem’s charismatic, energetic and genuine personality. He does his work with a lot of integrity and holds a lot of pride in the community he has created. Serving up a bold yet simple menu, Syed believes that the power of a meal to comfort and excite people is unparalleled. “And what I’m doing with our franchise, with THG’s Hot Chicken–specializing in Nashville-style Hot Chicken Tenders—is very simple. But I just finished telling my chefs today, “Listen, when you clock in, we have a system. A system that we’ve built.” It’s going to be me, my three guys, including my sous chef and chef de cuisine, and we’re going to rock the house. That’s all we need. The epitome of team.” Throughout all these goals and achievements, Syed keeps family and community at the center of his story. “Community wise, I stuck to my roots, I listened to what my parents told me, “Take care of yours first.” So I would always cater to the Indian/Pakistani community. Make everything halal. It didn’t matter if you are Muslim or not. I was just targeting the Indian/Pakistani demographic specifically. That became us doing events where people recognized me as my parent’s son. It would be an order of burgers, tenders, tacos, but also they want two trays of biryani.”

Within the next week, Chef Aleem will be opening his first restaurant, THG’s Hot Chicken, in Scarborough. The restaurant is designed to be fully accessible to both employees and patrons. In ten years, Aleem hopes to have ten more restaurants across the Northeast. “At the end of the day, I’m doing this because that’s what I want to do. And it was what I was doing before I became paralyzed. And it’s the one thing I’m really good at. I’m just following my heart.”

When asked where he feels like he most belongs, Chef Aleem took the opportunity to quote a mentor of his, Uncle Chin, who taught Syed that it’s not about finding a place you belong, rather making a space for yourself to be. “He told me this when I was freaking out and didn’t know what to do. ‘Everyone’s a star, Aleem. It’s up to us to dig down into our hearts and pull that star out and show it to the whole world.’”