This essay is part of our editorial series, Work in Progress on design and restaurant labor.

How might we re-conceptualize the role of a line cook? Cooking affords a skillset of time management, creative use of space, and execution that can be incredibly valuable and transferable to other professions. As Dylan Takao, a line cook at the wine bar and restaurant Four Horseman in Brooklyn put it, “Good or bad, that dish will stay with someone,” and while the idea of the food certainly lives on beyond the consumption of it, a lot of the real value within a dining experience cannot be perceived through taste alone.

All photographs by Emma Leigh Macdonald. Special thanks to Four Horseman.

The kitchen is the site of a collective process—line cooks are responsible for carrying out the execution of a chef’s vision, but they must bring their own creativity and strategy. My family owned a restaurant but it wasn’t until after graduating college and working at a human-centered design firm that I started cooking professionally. I quickly learned that the ability to make a béarnaise sauce and finish salads with the right amount of salt and acidity would prove insufficient for getting me through the rigors of an average workday in a professional kitchen. If I wasn’t completely set up when the first customer came in, my adrenaline levels would spike as each ticket came in. To succeed as a line cook, I was going to have to use strategic project management to cope with the constraints of time and space in the kitchen. I would constantly redesign my station as new dishes were added to the menu—grouping together ingredients by dish, carefully selecting the quantity needed on my station to avoid running out of product while simultaneously ensuring I wasn’t overcrowding my station to have enough space to plate my dishes. As I was working on the line, I realized that cooking is ultimately a way of thinking about problem solving. By thinking about cooking like a methodology, much like design, we can bring awareness to the complex skillset one needs to be a line cook.

Cooks spend their days working on many seemingly reductive projects that are assembled during service. Several cooks shared insights into their day to day routines and provided insights into the thought processes that afford them the ability to cook for hundreds of people each night. Dylan Takao, of the Four Horseman; Grace Brannigan from Lil’ Deb’s Oasis, Hudson, New York; Margot Timboe of Rose Mary in Chicago; Charmaine Lau at 181 at Fortnum & Mason in Hong Kong; and Jess Naldo, who has experience working the line as a short-order cook at the highest levels of fine dining both abroad and in the United States, all provided insights into a profession that can feel undervalued, misunderstood and, simultaneously, romanticized.

Time

Despite making hundreds of pastas and risottos during service, the work begins long before most cooks get to clock in. Margot Timboe plans out how she will divide up her prep on her morning commute: “We divide the prep up, usually between daily use and projects.” Daily use entails “lemon juice, any sort of dicing [or similar prep of fresh ingredients] or cutting butter. Frying or grilling any mushrooms for garnish is kind of like small stuff that you can do while you’re sitting upstairs on the station,” while braises and sauces are projects that can take multiple days, but can be completed ahead of time.

Line cooks are always task-switching; some projects require high levels of attention to detail. “I have five projects and another four or five knife cuts. Obviously, the projects are some things that can work in the background while you’re cutting vegetables or cutting fish. And then some projects are definitely going to need to be hands-on, like making a lemon curd or something—you can’t really step away from that project.” Some projects that take several days may not be, “super labor intensive, but the timing of it is what’s the most difficult part,” according to Margot.

I want to come in and not actually have to do anything for that day unless it’s a daily project and prepping projects for the next few days” says Dylan. Professional cooks also have to negotiate between scarcity of time and raw products that can spoil. Getting too, as cooks say, “up on things” can quickly become negative on the books of time. “You don’t want to get too ahead on things like that because celery will start to die, dry out, get a little weird” attests Dylan.

Time management can seem like a daunting concept to any professional, but as Charmaine Lau says, “There’s no choice in the kitchen, you have to do it. The order is here, the customer is here, they’re waiting. So, you just have to do it.”

Space

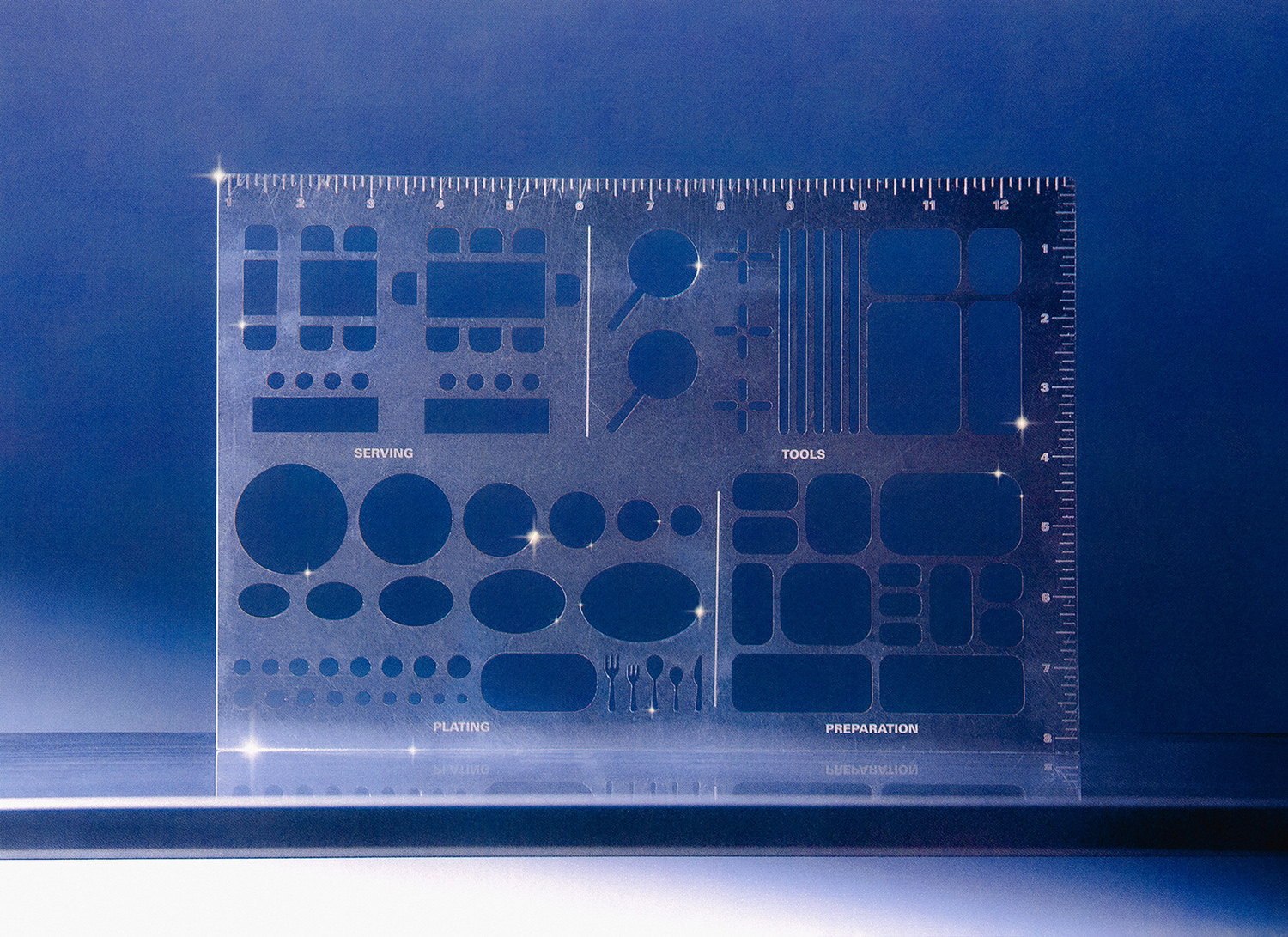

From inspiration to ideation to implementation beyond transforming the food itself, cooks are constantly prototyping the design of the space itself. As Margot shared, “Setting up the station always comes first”; cooks assemble their line with different permutations of third pans/six pans/nine pans testing out different frameworks and adjusting after each service to maximize the use of the space.1 There is a level of improvisation, and over time small adjustments are made until a final form is utilized for the duration of the menu. Line cooks create their own user experience, where they are at the center, from prep to the line. In addition to the line—where cooks assemble their reductive projects into cohesive dishes for the end user—they design and redesign their built environments to complete their prep. Charmaine, a left-handed cook, places unprocessed product to the right of the cutting board, saving themselves small movements. Margot layers a chinois—a fine mesh stainless steel strainer—over a Cambro to strain the jus directly into its storage container an efficiency that reduces the number of dirty dishes.

In professional kitchens, being able to identify usable outlets is advantageous: “Just finding an outlet downstairs is the biggest constraint of space, and a lot of the products on my station need a blender. We have six sauces that need to be blended, and some days I’ll just kind of group all my blender projects into one day,” says Margot.

Cooks are operating within an ecosystem of cooking tools and implements: cutting boards, ovens, burners, a Vitamix, a Robot Coupe, a Pacojet, and if you are lucky, a Thermomix. In scarcity, cooks have to reimagine the purpose of certain tools; Charmain had to prepare a savory aioli with a Pacojet, traditionally used to make ice cream, and when ”I forgot to wash the blade, [I was accused of making the] ice cream taste like pickles.”

Cooking exposes the physical and relational limits of what it means to be human, and I believe there is a lot of potential for cooks and designers to inform each other’s work and approach to solving problems. Cooks are designers with an audience, and designers can learn from their rapid ideation, improvisation and prototyping techniques. Design has the potential to help cooks make sense of their work and provide a framework to further optimize an intuitive process. Design can help surface the extent to which cooking is “skilled” labor,2 and provide fellowship with professionals in industries beyond design.

- 2. Ahem, a note to NYC Mayor Eric Adams