This essay is part of our editorial series, Work in Progress on design and restaurant labor.

I often feel like I am playing a superficial role in the world around me, simply going through the motions, growing ever distant from nature. Working as a chef at the London udon restaurant Koya Bar, I recognized that a meal points to the intersection of nature and culture. The experience helped me realize that nature is not a romanticized or pristine vision of unlimited bounty or wilderness. Nature does not stand apart from human activity––I have to actively restore and collaborate with organic agencies, people, and natural resources to carry on. I noticed how the restaurant’s culture shaped my values—my food choices and how I perceive and correspond with the environment. I eventually understood that as a chef, my labor and effort creates the quality of a meal. I can produce better, more sustainable meals through continuous correspondence with the conditions of my environment. This correspondence also describes a new model by which today’s “sustainable restaurants” can operate.

Today, people are forced to consider the sustainability of everything. According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, the “sustainability of everything” does not refer to or consist of the sum of individual things. Everything is not a totality but rather a “carrying on.”1 In an attempt to provide a new ecological perception of the environment, Ingold looks for other ways of knowing. Instead of acknowledging specific boundaries or differences between things, he seeks a “correspondence of parts” and discusses how things are interrelated and always in motion—becoming instead of being. Since everything is in motion, when things bump into each other and intersect, not only do they become something new, but he imagines that they form knots. Given the power of human agency in nature, Ingold’s assembly of “knots” is handy for recognizing that humans are the most influential creators of knots on earth. Everything we produce is a knot. Depending on the process used, knots can have positive and/or negative environmental consequences.

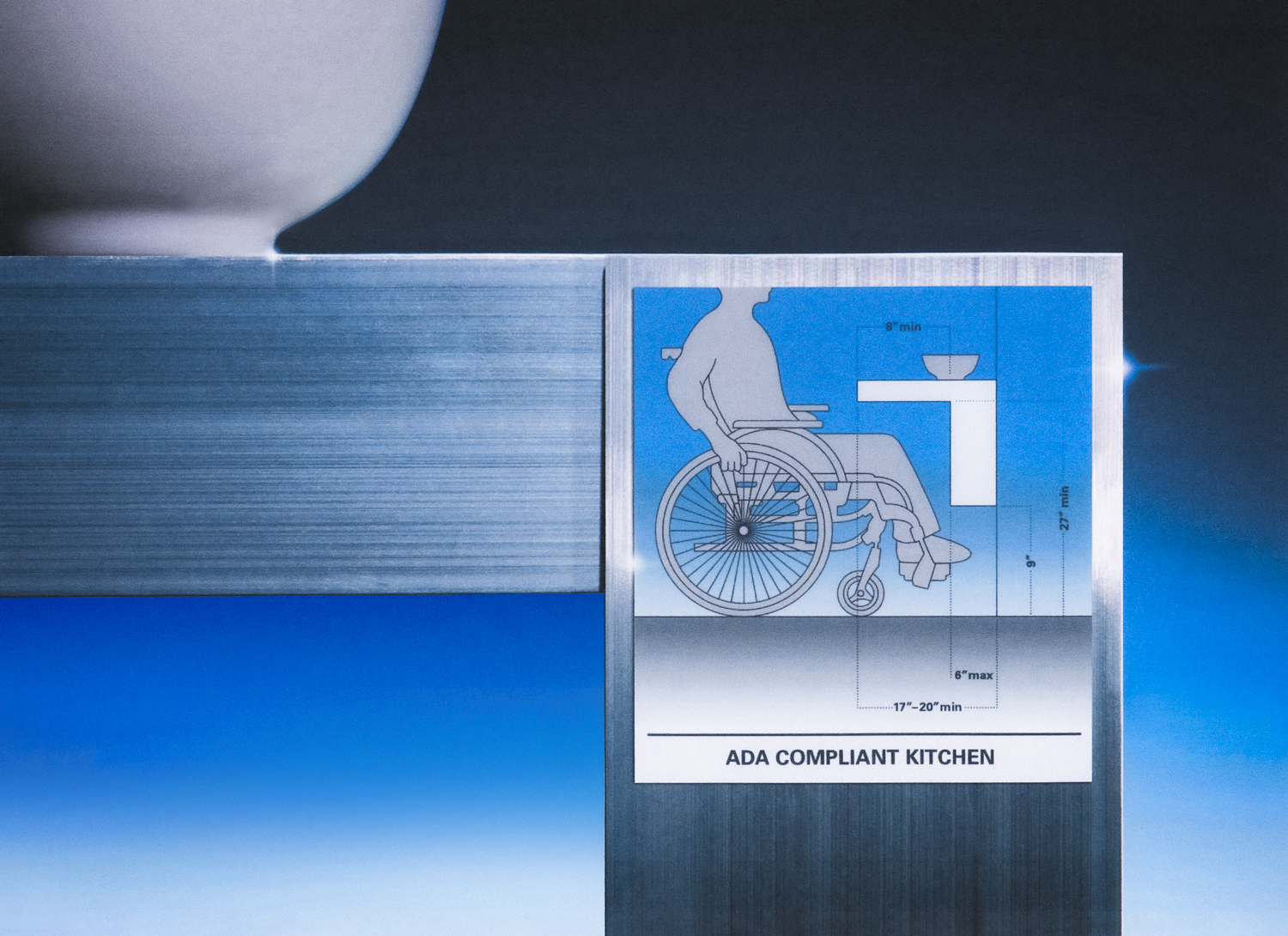

A restaurant is a knot of nature and culture created by people. This third space outside our homes and workplaces weaves a city’s fabric, nourishing its people and the relationships they have with each other, community, and economy. It offers an antidote to the seemingly inevitable momentum towards standardization and uniformity that permeates almost every other part of our lives. The restaurant is perfectly positioned to support diversity in production and consumption—promoting new and local crop varieties, animal breeds, and under-utilized crops; nurturing biocultural heritage and traditional knowledge; and catalyzing change through innovative kitchens that focus on research and development. Chefs function as a resource for the restaurant and the environment. Their labor and identity can steer a restaurant toward sustainable change by advocating for the use of biodiverse ingredients from their own cultural perspective. The knowledge of chef-artisans can therefore reinforce new linkages between biological and cultural diversity within urban landscapes.

***

Throughout the years I spent working in food marketing, Koya Bar provided an oasis of calm and relief from the pace of London’s city life. The restaurant was a regular yet unintentional self-care ritual. I purposefully came to dine alone, nourish my body, and restore my mind. After a long day of commuting and running errands, I often joined the queue for a seat at Koya’s bar. With only a counter between the chefs at work and me, I was forced to pay attention to my surroundings. While enjoying a bowl of udon, the norms of everyday life appear to suspend in time. When a customer referred to the restaurant as his “temple to pleasure,” I considered our commonalities. I quickly observed how many customers also shared the ritual of the repast in splendid solitude. What was it about the restaurant that had brought us there?

At the time, I craved a shift in my career from working at an office job selling food to working directly with food. So I applied and got a job at Koya Bar as a chef. Upon reflection, I grew conscious that my experience working on the other side of the counter provided specific insights into how Koya gives diners a chance to encounter something so ambiguously special––something different. These insights could also pave a way forward for other restaurants which seek to balance their commercial priorities with their environmental concerns. My primary observation, and shock to the system, was the level and intensity of the work. A restaurant meal became notable because it possesses magical properties that have become separated from the laborer that produces them. The characteristics of the chef’s labor appear to be the natural characteristics of material objects, finished products, not processes. Second, therefore, was Koya’s approach to sourcing ingredients nearby.

Chefs function as a resource for the restaurant and the environment. Their labor and identity can steer a restaurant toward sustainable change by advocating for the use of biodiverse ingredients from their own cultural perspective.

Executive chef and co-founder Shuko Oda explains that she associates food with memory. Although she was not raised in Japan, she still carries on her own adapted taste for its cuisine. “I guess I grew up everywhere. Many Japanese people say I’m not Japanese, and many English people say I’m not English because I sound American too.” Buying from a local farm, known as NamaYasai, which experiments with growing crops from Japan, made perfect sense. It was a lot more sustainable, but it is also what makes the restaurant unique, in a way, for people who are Japanese or not Japanese to work with and enjoy these ingredients. “The kind of vegetables that NamaYasai provides feels really natural to me. I think the dishes I make from their vegetables and the palate and the idea of the dishes are more a result of flavors I ate in the past; maybe it was something my mom made in Los Angeles. But she’s Japanese, and it probably had soy sauce in it somewhere; maybe that is how I remember flavors. And that’s how I put a dish together. I make sure that there is a Japanese feel in the dish somewhere.”

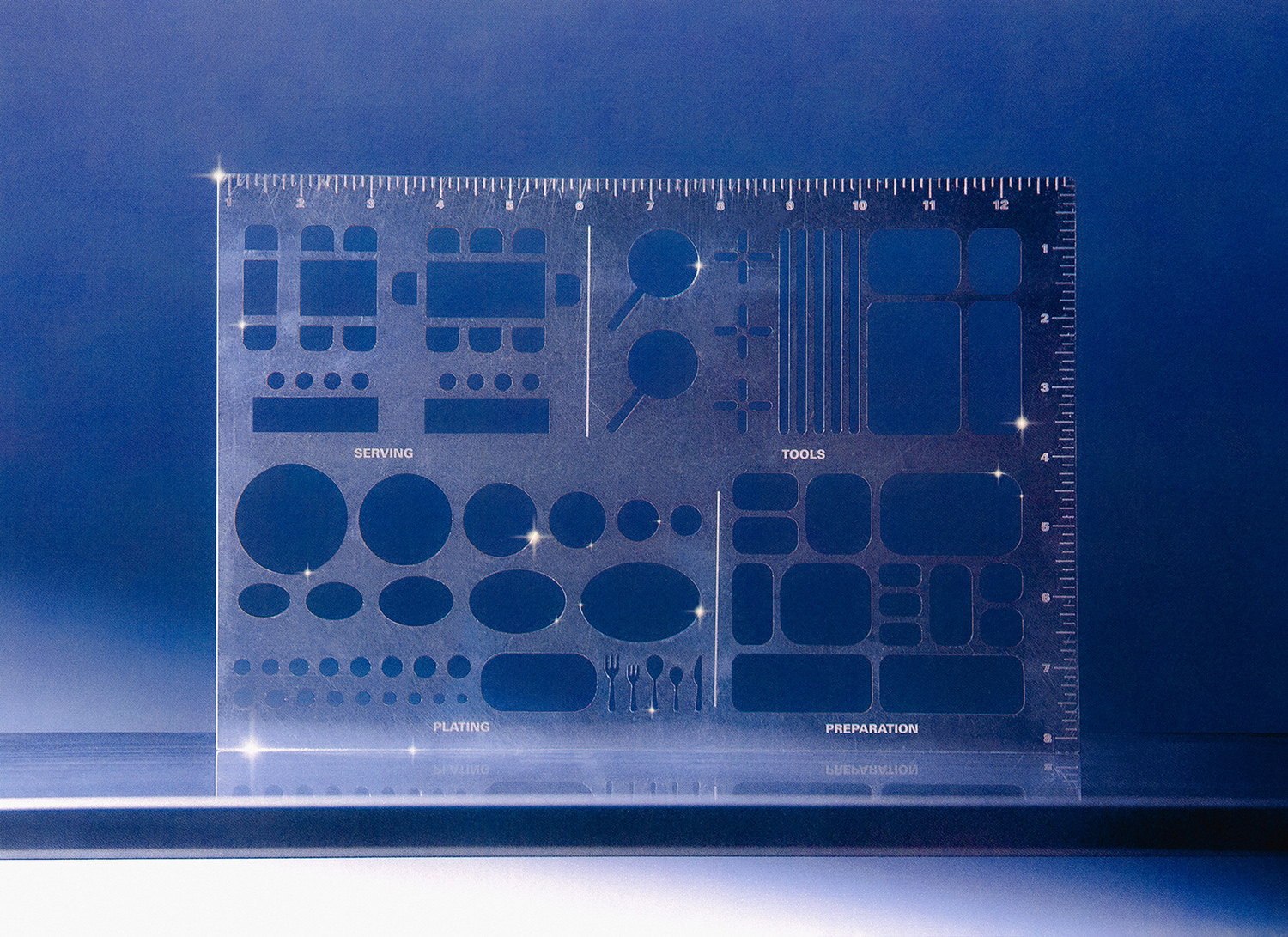

While Koya specializes in traditional udon noodles, the menu has become a different thing to different people––it is the kind of place where anyone can build their own experience. As former head chef turned farmer Edgar Wallace explains, the menu has two levels: the macro and the micro. The macro creates the framework for Koya’s menu diversity. There is the noodle bar, which is the restaurant’s foundation. Its concept is repetitive and consistent, “in a good way,” he emphasizes. While the restaurant tries to get things as locally as possible to reflect the seasons, it is good to have some routine to fit these new variables into. Layering the seasonal “special stuff” from smaller suppliers on top of staple products like dashi and udon creates the specials board (the micro), which changes weekly.

Ingold’s reference to the “sustainability of everything” does not look for new ways to carry on doing what we have been doing in the past (with less detriment to the environment). Instead, he considers the kind of world that will have a place for us all in it, including future generations. For chef Oda, all chefs must have a space to talk, demonstrate their ‘feel’ for things, and renegotiate their ideas and knowledge, even if it does not end up on the specials board. The restaurant’s kitchen is a space that allows different people to share, learn and combine other cultural ideas they never imagined would work together. As a result, it produces sustainable ‘Koya’ versions of the dishes that the chefs grew up eating. Chef Oda says that these versions remind her of Japanese dishes––only new ones. She describes the “sweetness” and “warmth” of those ingeniously creative “sparkle moments” as the thing that keeps her going. Chef Oda, therefore, carries on the taste of Japanese udon noodles by defining her sense of belonging through personal relationships and various geographic locations. She combines locally sourced ingredients with memories of the meals she grew up eating and the memories of others, creating a rooted yet knotted taste of local and global.

Today, a tremendous amount of time is spent trying to mimic past “traditional” practices for conservation purposes. However, Ingold highlights the static nature of this approach. He argues against the assumption that the earth is a still-standing reserve. Instead, he reminds us of the dynamic relationship and direction that a knot represents. Regarding our future, he favors the idea of carrying on, continuing to learn, grow, build, connect, and teach, as that is the cycle of life. In Ingold’s view, artisans—including chefs, cooks, designers, and farmers—offer alternative ways of understanding the world, which can create new conditions for intervention and possibility. Chef Oda, for example, doesn’t directly replicate the dishes she grew up eating, but instead, reinvents them in a way that feels honest yet integrated with her local environment. She cultivates an economy based around community and inclusion which is the type of politics that is needed to embark upon a process of sustainable economic change––create knots that are entirely different from those created in the past.

NamaYasai combines British and Japanese perspectives of the environment to seek parallels between these geographic locations in order to foster previously unimaginable biodiversity and consequently provide its customers with something unique and special that they can serve to cosmopolitan diners. The farm, its laborers, landscape, and weather conditions determine what restaurants will dish up instead of the other way around. Like nature, the relationship between this farm and its customers is unpredictable. Despite the uncertainty of what the farm will have to offer, Chef Oda likens the farm to a continuous source of inspiration. Due to the farm’s proximity to urban restaurants, NamaYasai can bring nature and all of its compelling attributes, such as freshness and flavor, back into the city, via the restaurant. Therefore, the dynamic relationship between the farm, the landscape, the restaurant, and the creation of a meal, takes place in an ongoing cycle that continuously creates something new––something special.

A meal represents a web of entanglement, interdependent relationships, and multiple dimensions (connections and layers), each benefiting the other for sustainability. It demonstrates our role in nurturing the environment while also nurturing ourselves—the harmony, fluidity, and hardship of this coexistence. Creating a meal encourages an understanding and engagement with nature that does not exist outside what it means to be human. This comprehension encompasses a realization that we too are a part of and play a role in nature—we cannot outsmart or control it, but our culture can influence and shape it. This understanding connects us to the material and non-material forces surrounding and inhabiting us, like the microbes that live in our guts and the nutrients that grow within our soils. At Koya Bar, this is a process that is continually carrying on, painting a dynamic picture of nature, culture, and the human and nonhuman relationships that play a pivotal role in the business of sustainability.