MOLD’s series on Urban Ecologies is an exploration of how the ever-evolving built environment affects the way we think about, grow, and eat food.

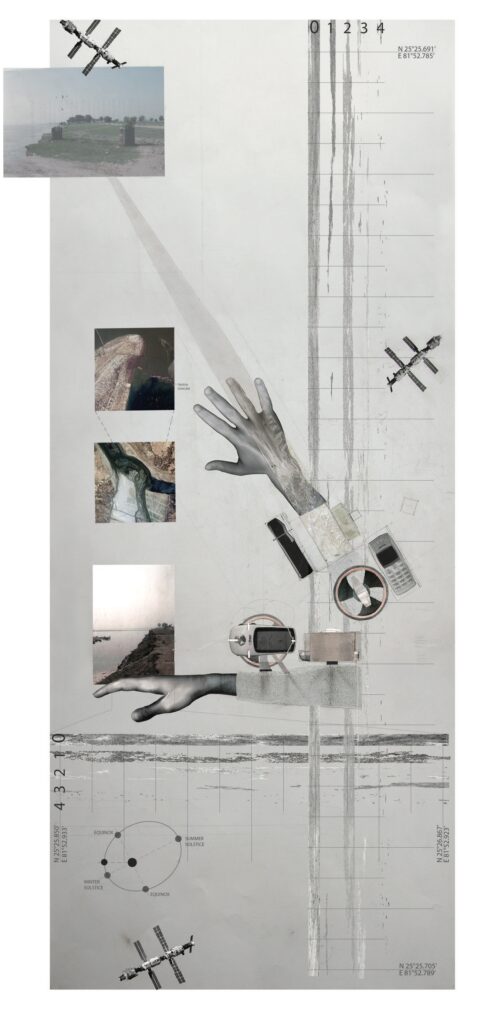

For almost two decades, the architect and geographer, Anthony Acciavatti, has been tracing the riverbanks of the Ganges River. As the world’s most densely populated river basin, the Ganges has provided an evolving laboratory for water infrastructure. Subject to seasonal monsoons, the infrastructure of the Ganges River basin as well as the agricultural practices and adaptations of those who live alongside it provide a case study for a water future constantly under flux. The author of Ganges Water Machine, Anthony combines cartography and historical context to create what he calls a dynamic atlas—a tool for understanding the transformations of a body of water. In our conversation, Anthony unpacks how water infrastructure can be used to subvert attitudes of scarcity and also makes an argument for transforming infrastructure into monuments through design.

Isabel Ling:

In this moment of climate anxiety, what is your experience studying water?

Anthony Acciavatti:

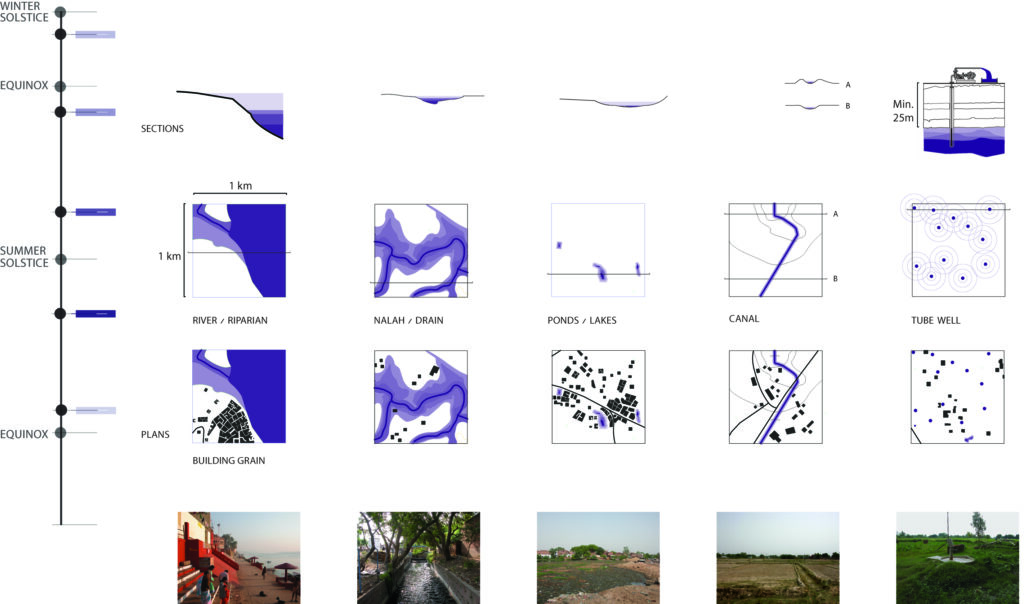

Ecologists often look through the lens of “indicator species” to measure and explain environmental change. By focusing on say hawks, an ecologist can learn a great deal about all the other constituents that make up the habitats of hawks. For me water is an equally potent lens to measure and draw social and political changes together. Drawing the ways in which surface water bodies, like lakes and rivers, overlap with sub-surface water bodies, like aquifers, can tell us a great deal about the ways in which biophysical processes like rainfall and groundwater recharge interface with urban growth and agricultural production.

IL:

There has been a shift in our collective consciousness toward treating water with scarcity— as someone who works/interacts closely with water/ water infrastructure, how do you see this influencing and evolving our future relationship with water?

AA:

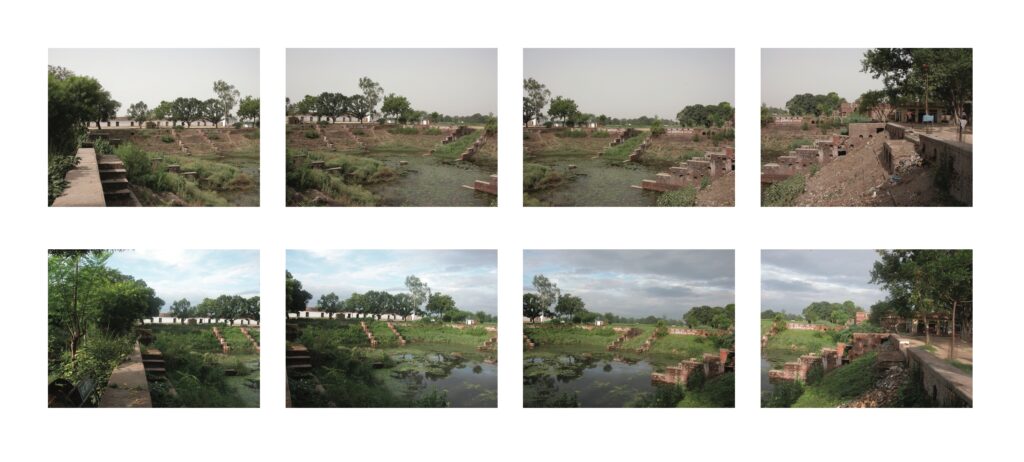

I see scarcity and abundance as being integral to how we can collectively shape new forms of civic architecture and infrastructure for water harvesting and distribution. For nearly two decades I have been working in India’s largest and most populous state of Uttar Pradesh. It is home to nearly 200 million people living in an area half the size of California and produces close to 20 percent of the nation’s food grains. A patchwork of farms and cities, it is one of the most flood and drought prone states in all of India. In short, inhabitants annually experience extreme bouts of water scarcity and abundance. As more and more of the world faces similar cycles of extreme environmental uncertainty, it behooves us to see how systems of water harvesting and distribution, like stepwells and tanks, along with canals and bore wells, can shape new forms of civic hydraulic architecture. This region can lead the way in models of water banking that other parts of the world can learn from and adopt over time.

IL:

Could you tell us about your current work studying water infrastructure in the Ganges River Basin?

AA:

Currently, I am working on a series of proposals to reimagine water infrastructure like stepwells and bore wells. For stepwells, which are these water tanks developed centuries ago to store rainwater from the monsoons for irrigation and bathing as well as drinking, it is about hallucinating how we can design these infrastructures in a way that addresses some of the basin’s most pressing and overlapping issues: water insecurity, public space, and housing. Rather than placing water collection in one silo and public space in another, we’re developing a 21st century stepwell that makes the collection and distribution of water a new civic spine for organizing the growth of neighborhoods and public space, which is in real demand. In order to move away from dispersed forms of settlement that are ubiquitous today and cultivate a larger commons, housing and public space can be clustered around these civic monuments to create new models for domestic space and recreation. Historically, stepwells just kept water in the excavated space itself. What we will be doing is looking at how to incorporate housing and public space as well as tubewells, which are bore wells that draw up groundwater for drinking and agriculture. These are typically privately-owned, and we want to think about how to repurpose them with community-based systems.

Today, water table levels are dropping so dramatically in some of these areas that it really requires thinking in terms of community cooperation as opposed to thinking and acting individually. The proliferation of privately-owned tubewells really began in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and l guided by this idea that if you can afford [a well] you can sink one. As a result, tubewells began to replace other surface water bodies like canals and stepwells. It is paramount to incorporate or adapt tubewells to other existing infrastructures, as opposed to being monofunctional about them. It’s super important as well because so much of groundwater is used for crop irrigation. If groundwater levels drop and are not recharged, there is a real threat of drought and food shortages. So that’s quite critical in addition to everyday consumption of drinking water.

New forms of civic infrastructure like stepwells can create a new form of monumentality that can draw the public in so there can be a visceral, palpable sense of what this infrastructure is contributing to that people can also enjoy.

IL:

In your research you talk about decentralization in the existing infrastructure of the Ganges River Basin, specifically with bore wells. Could you speak about that as well as its ramifications?

AA:

Decentralization of water, especially in the middle of the 20th century, is a result of the state putting the responsibility of drawing up groundwater to irrigate agriculture in the hands of individual farmers and landholders, rather than creating networks of water distribution. Which, in some ways, sounds really good and sometimes did work really well. The issue was that people who could actually afford their own tubewell were far from the majority, so it really created a have and have-not situation. Community tubewells would often fall into disrepair for a whole host of reasons that varied from there being no money set aside to for maintenance and repair or no way to repair them because all of the parts were produced abroad and India had stringent import restrictions of foreign products. In short, the tubewell economy became very privatized and unregulated.

Although there have been some new regulations more recently in some parts of the country, it’s still a very bottom-up system that is not regulated or closely monitored by government or non-government organizations. When you are extracting groundwater faster than it is being replenished by the monsoons, then water table levels drop and there is a cascading effect. For instance, imagine a farmer with limited means who depends on a shallow hand pump to draw water for drinking and irrigation is adjacent to a wealthier farmer who has a deep tubewell. The shallow hand pump will go dry before the tube well. So in some cases, it’s having a ripple effect in terms of exacerbating economic differences. The resilient part of it is that people who have tubewells have created secondary water markets, where they will sell access to their tubewells to their neighbors, to irrigate their crops. So people do find ways to adapt to these precarious conditions. New Delhi is an object lesson when it comes to these cascading effects. It’s a city with a population around 20 million people. There are probably 1 million operating tubewells there, which makes one for every 20 people. Yet there are huge water disparities because some of those tubewells might just be servicing less than 20 people or a single family. Another externality is that in a place like Delhi, you’re having subsidence, where water is being extracted so fast it’s causing buildings to sink into the ground. The lack of oversight, combined with incentives to work individually as opposed to collectively, produces all kinds of side effects. I’m not proposing that we count all of the tubewells and figure out where they are all at but how do you build incentives for people to want to work together on them as opposed to thinking about them so individually.

IL:

As someone who has studied the same body of water for almost two decades, how has your work changed as a response to climate change?

AA:

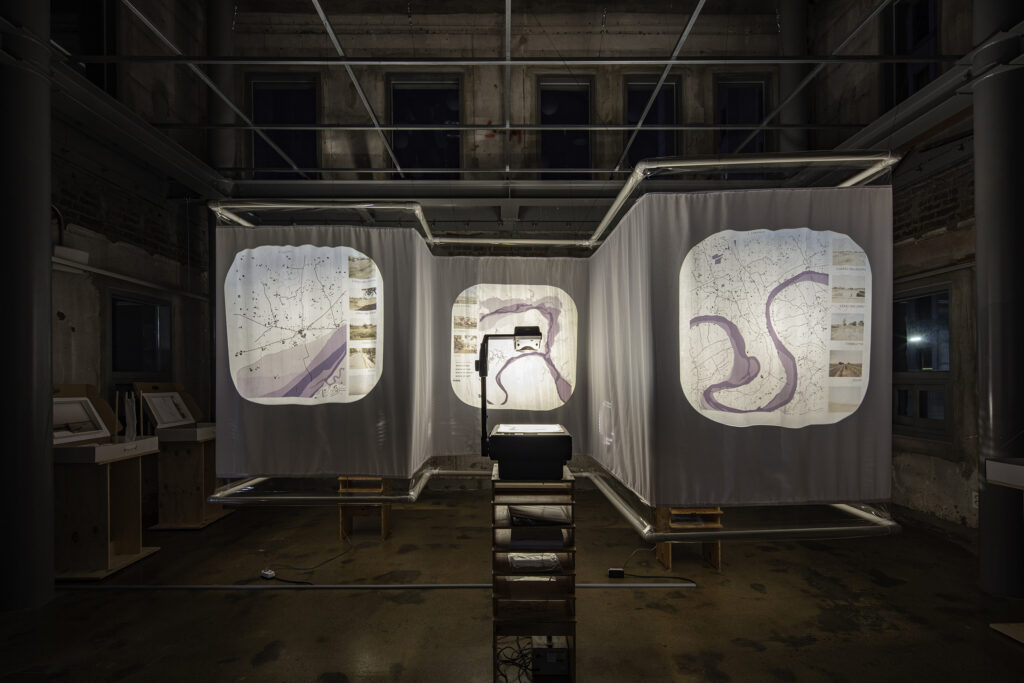

When I speak with people in the basin about how they imagine climate change to disrupt their lives, I am met with some surprise. More often than not, people tell me that the monsoon is and always has been capricious and that they will adapt. Some years they will have droughts followed by years of floods. In short, people are saying, “We’re always confronting extremes.” For me, as a designer, I am invested in understanding how people already incorporate the deep rhythms of the monsoons into their lives. The challenge has been to make drawings that incorporate the dynamism of the basin—to create what I call a dynamic atlas. The best way I know to explain this dynamic atlas is to speak about it in terms of couture versus ready to wear. Most cartographic drawings are made like couture from Christian Dior or Givenchy, which is to say that it’s custom made to fit a single person’s body. My drawings are more like ready to wear from Uniqlo or H&M, you can gain a few kilos or lose a few kilos and they still fit. I do that by drawing the ways that surface water bodies, like tanks and river channels, along with the underground water conditions, like water table levels, expand and contract with the monsoons. This kind of flexibility to alter a garment is known as a seam allowance. And my drawings of the basin are full of these kinds of seam allowances.

IL:

What necessary changes and investments need to be made to water infrastructure in order to create a more resilient future?

AA:

Investing in a middle scale to reframe environmental uncertainty is important. Over the past two decades, I have seen how governments and non-government organizations have vacillated between supposedly top-down systems of water management, like the Army Corps of Engineers in the United States, and more supposedly bottom-up systems, like bore wells in the American southwest and much of South Asia to supply drinking water and irrigation. What remains missing is a middle scale that ties these different scales and politics of water management together. Drawings are needed at this middle scale to not only show overlaps between these seemingly juxtaposed systems, but also so that people can have a meaningful conversation about how to negotiate environmental uncertainty together.

One of the things that is super crucial in a place like India, with population growing in the way that it is, is thinking about planning and urban design in a four dimensional way, including groundwater recharge as a way of starting to plan out where growth happens and use that as a structure. This provides a way to incorporate real estate pressures and growth to better meet water needs for drinking and agriculture. The fascinating part about it, from the point of view of an architect, is that it puts pressure all the way on the scale of an architectural building to an urban block, a neighborhood, a city, even regional scales. Thinking across scales is crucial. Synthesizing part-to-whole relationships becomes really important. And that is as much about educating non-specialists as it is educating policy-makers and government officials.

I would just say one of the things that I always find is that one of the reasons that politicians are never crazy about soft infrastructures that abate and filtrate pollutants, like bioswales and wetlands, is because they can’t point to it as a monument. Whereas a sewer treatment plant you can. Even if that sewage treatment plant only has electricity a couple of hours a day to operate, it still has that sense of monumentality. So I think also building new forms of civic infrastructure like parks and stepwells and other water bodies that have a public aspect to them can create a new form of monumentality that can draw the public in so that there is just a really visceral, palpable sense of what this is contributing to and that people can enjoy. I think that is where design has something to offer in terms of how to create those kinds of spaces in a densely populated and agriculturally populated area.

IL:

Beyond monumentality, what other things do you think designers should keep in mind when designing for water infrastructure?

AA:

I think one of the things that really affects groundwater recharge in India is the proliferation of non-permeable surfaces; like roads and buildings. So there’s actually a real environmental incentive to build more densely, compactly, and even taller in some cases–all in an effort to occupy less space. Less diffuse kinds of urban growth offer more opportunities to create the kinds of social and physical infrastructures that I’ve mentioned.. Pairing water distribution and extraction with groundwater recharge and building heights as almost a new form of zoning is, I think, something that designers can play an important role in. Another great thing about that, is the open spaces that end up getting created [when density is distributed vertically], is how can we create new forms of parks, even pocket parks, along with larger scale parks. The more we can engage the different scale and density of these patches, the more opportunities there are for increasing groundwater recharge.

IL:

What is something you think people should know about water? What is something people can do to change their personal relationships with water?

AA:

Reorienting our sense of water from the singular to a plurality of waters is crucial to the issues many people and regions are facing today. When we think of waters and their myriad mixtures, groundwater and rainwater tell us where waters are coming from and how we can better integrate them into our lives.