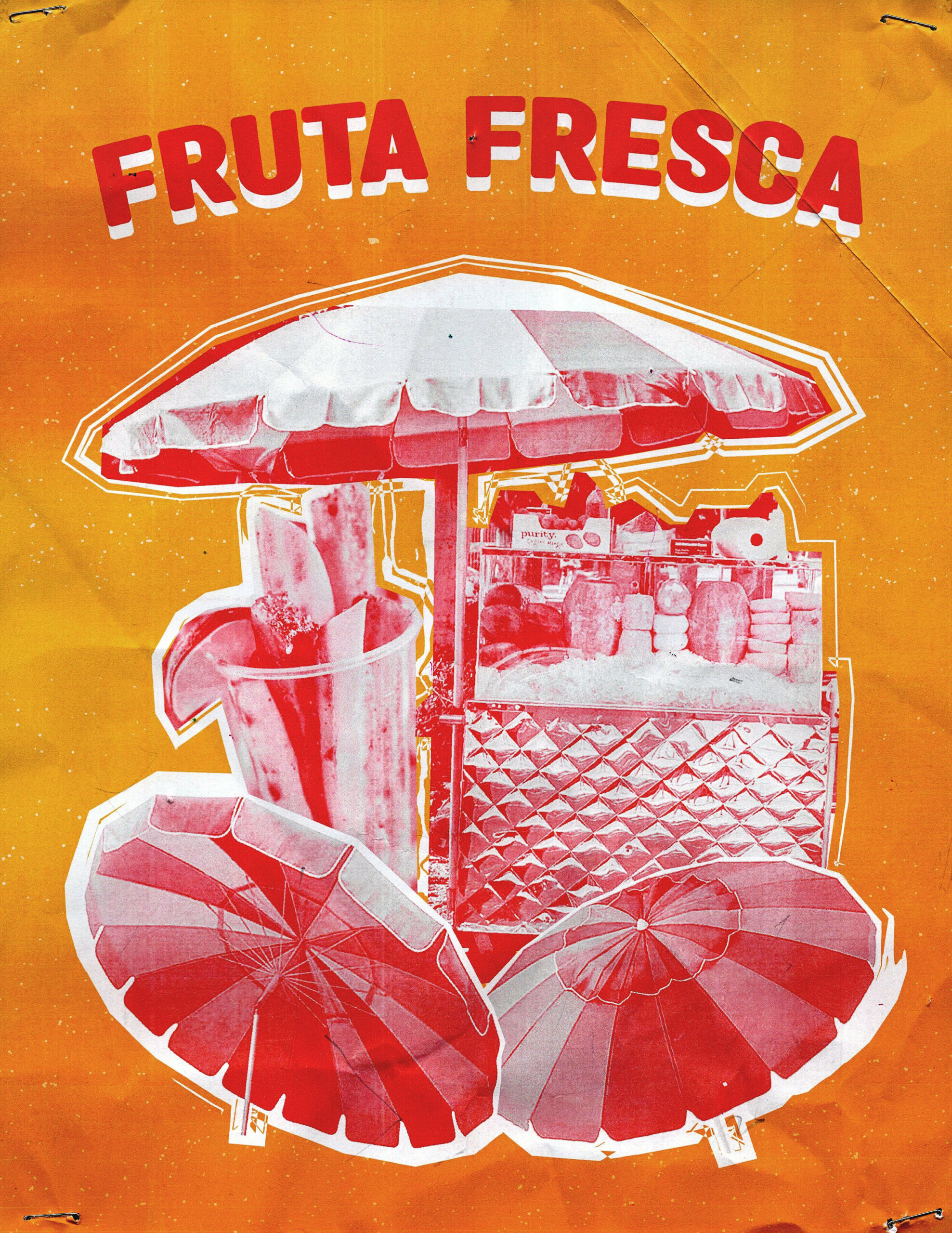

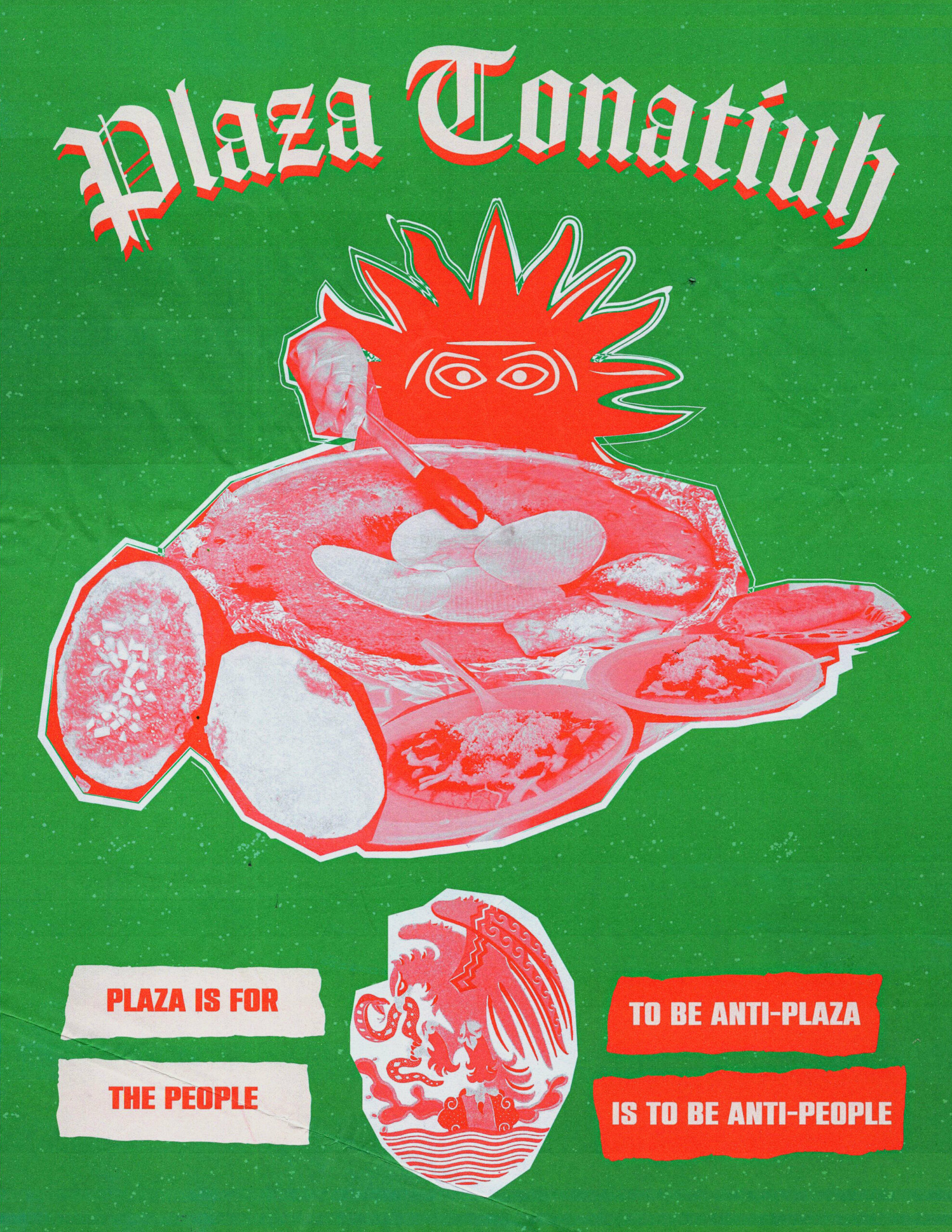

In this year’s annual list of 100 best restaurants to eat in New York City, Pete Wells, a longtime food critic, included Corona Plaza’s vendors in between Michelin-decorated establishments like Rezdora and Jean-Georges’ ABCV. However, earlier this year, on July 27th, officers from the Department of Sanitation and from NYPD swept through the Plaza, disbursing the vendors, shuttering the canopies and closing it all down. Last week, the Adams administration signaled that the Plaza would be opened once again, albeit at a much smaller scale—allowing only 14 of the 80 stalls to return. This story of Corona Plaza is just one snippet of a century-old tussle between vendors and city administration. From bagels to biriyanis and churros to fuchkas, New York City’s food carts and its street vendors make up a core part of the city experience for residents and visitors alike. And yet, these hard-working, mostly immigrant vendors, who have gone on to enrich not just the gastronomic landscape but the overall cultural fabric of the city, often have to negotiate complex bureaucracy, an exploitative black market, and relentless harassment from oversight and law enforcement personnel. A look back in history, however, shows that street vendors have always played a part in New York City’s history.

Vending and the City

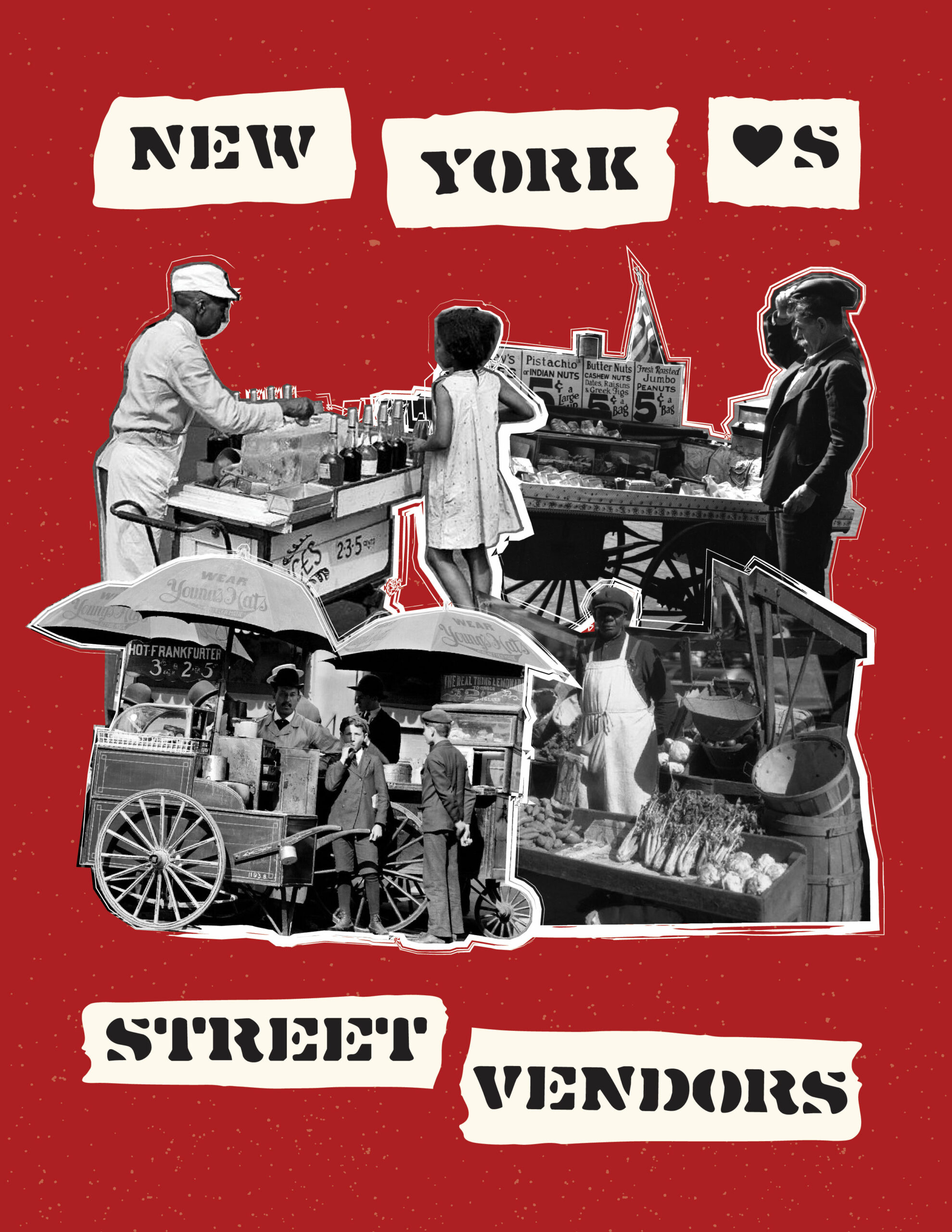

The first ‘street vendors’ in New York were pushcarts hawking oysters that had been harvested from the New York harbor in the 1700s. Around the 1840s, New York experienced a new wave of European immigrants—mostly Irish and German—who moved into the tenement apartments of the Lower East Side. These newly arrived immigrants further contributed to New York’s bustling streets, and would rent a pushcart for a quarter a day and set up shop on the sidewalk selling foods from their home countries. The turn of the century coincided with the arrival of Eastern European and Jewish immigrants, who had to jostle for space to sell knishes, pastrami, pickles, and salmon over cream cheese-smeared bagels. Hard as it might be to imagine today, most of New York’s flagship stores like Bloomingdales, Macy’s, D’Agostinos, even Goldman Sachs, first began as humble pushcarts.

In the aftermath of the second World War, the newest New Yorkers were coming from places like Puerto Rico in the mid-1940s to early 1950s and Dominican Republic in the 1960s. Fast forward seventy years and the city’s street vendors today are a diverse mix of immigrants hailing from over 80 different countries. Among the street vendors who are members of the Street Vendor Project (a membership based advocacy organization), an estimated 25 percent were Mexicans, followed by Ecuadorians (20 percent), Senegalese (15 percent), Egyptians (14 percent), Bangladeshis (6 percent), Chinese (3 percent), and U.S.-born war veterans (5 percent). But even as falafels have replaced pickles, the tensions between street vendors, brick-and-mortar stores, and government agencies have largely remained the same.

Despite growing demand, vending licenses and permit caps are fixed in time

In the decades from the time the first street vendor was formally recorded in Hester Street in 1866 to when Mayor La Guardia created the Department of Public Markets in the 1940s, the number of open-air pushcart vendors swelled from an estimated 2,500 to around 14,000. The dramatic increase was a result of the arrival of millions of new immigrants, who resorted to vending to find an economic foothold in a period of massive unemployment during the Great Depression. The resulting overcrowding of open-air pushcarts forced the then City administration to heed calls to ‘reform and regulate’ the vendors. In response, Mayor La Guardia created the Essex Market and the Arthur Avenue indoor retail market spaces, both of which continue to thrive in their present-day iterations. It was during this time that Mayor LaGaurdia also instituted the street vendor licensing system that required street vendors to register for a license in order to sell their products, capping the number of vending licenses at 1,200 in 1945. While general merchandise vendors need only a license to sell their wares, mobile food vendors need a license as well as a permit from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Vending licenses had remained at 1945 levels until Mayor Koch’s administration in the early 1980s, which saw the cap for food vending permits rise to 3,000, but capped the number of licenses available to general merchandise vendors at 853. Since then, while the number of licenses available to general merchandise vendors has remained unchanged at 853, the number of permits for food vendors has increased to 5,100. The waitlist for vendors who have applied for general merchandise vending licenses is estimated to be over 12,000 long and the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP), the agency in charge of handling street vending applications, has closed the waitlist to new entries since 2006. In an attempt to address the shortage of licenses, the de Blasio administration and the City Council passed legislation in 2021 to allow 4,000 supervisory licenses for food vendors to be issued over the next ten years, but none of these new licenses have been awarded yet. The current waitlist for vendors waiting to receive supervisory licenses is around 2,900.

Street vendors continue to be harassed by law enforcement

Lack of permits and licenses opens street vendors to harassment by City agencies, including NYPD, as in the case of Corona Plaza vendors. Continuing the legacy of Mayor La Guardia, most of the city’s Mayors have focused on making it harder for street vendors to operate by increasing enforcement (Dinkins), restricting more streets (Giuliani), and increasing fines (Bloomberg). However, Mayor Bloomberg is also credited with increasing permits for ‘green vendors’ in low-income neighborhoods. Under Mayor de Blasio, NYPD was advised against ticketing street vendors for minor violations of citing rules and availability of permits, and the oversight of street vending was transferred to DCWP. But the harassment has continued unabated. Even as Mayor Eric Adams has shifted the oversight of street vendors to the Department of Sanitation (DSNY), vendors continue to be cited, fined, arrested and even convicted for vending illegally. Beyond NYPD and officials from other city agencies like DSNY and DCWP, street vendors are under constant threat from Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), real estate developers, owners of brick-and-mortar storefronts and occasionally from residents in nearby buildings. Physical stores, including restaurants, view street vendors as competition, even though research has shown that they each serve different clienteles and are unlikely to be competing in the same market. In fact, there is also research to show that street vendors can increase the likelihood of New Yorkers opting for sit-down dining since their presence can attract more foot traffic to a neighborhood.

Street vendors have to live in a chronic state of financial precarity

Permits and licenses cost only a few hundred dollars in administrative fees, but vendors typically have to pay $6,000 to $8,000 thousand dollars on the black market to rent a permit. Many vendors accrue considerable debt to make this payment, often resorting to informal and predatory lenders to borrow the money and are forced to live in a state of chronic financial precarity, especially when their annual earnings are estimated to be around $30,000. The COVID-19 pandemic, and the related lockdowns and shift to remote work had significant negative impact on street vendors, often wiping off 80 percent of their businesses, by reducing foot traffic and customers. Given that a majority of these vendors were immigrants, many did not qualify to receive any kind of public assistance provided to small businesses e.g., the Paycheck Protection Program or the Small Business Administration debt relief.

Street vending can be reformed to improve the lives of the vendors

There are several straightforward solutions to making street vending a win-win for all New Yorkers. It is a productive economic activity that is generating important value to consumers. One study estimated that street vendors generated as estimated $71.2 million in city, state and federal taxes and contributed nearly $293 million to the city’s economy and supporting almost 18,000 jobs. Instead of penalizing it and relegating the vendors to the fringes of the city’s economy, we should legitimize and regulate vending as much as possible.

Echoing the recommendations of the Street Vendor Advisory Board, a pathway forward is outlined in a package of four bills that has been put together by the Street Vendor Justice campaign which is currently planned to be presented at a City Council hearing on December 15th, 2023. The package will put forward the following asks to address the various issues that we have discussed above: (1) gradually lift the cap on licenses and permits over five years so all those who want to vend can actually do so without having to pay extortionary rents in the black market or being harassed by law enforcement officers; (2) decriminalize street vending violations so that vendors face civil summonses and fines up to $1,000; (3) create a sub-division within the Department of Small Business Services that is dedicated to providing resources, training, education, outreach to all vendors regarding local laws and regulations; and finally (4) reform the siting rules so vendors can have greater leeway in locating their carts while not interrupting traffic, impeding pedestrians or blocking hydrants.

Proposed by a coalition of diverse non-profits seeking to improve the lives of vulnerable New Yorkers, and championed by Councilmembers hailing from all five of the city’s boroughs, the deliberation (and possible voting) on these bills represents momentous progress for street vendors. For the first time in decades, the City Council has a chance to formalize the street vending industry and fold it into the mainstream fabric of the city’s economy. If street vending is what makes New York, it is up to New Yorkers to make their voices heard in support of our fellow community members.