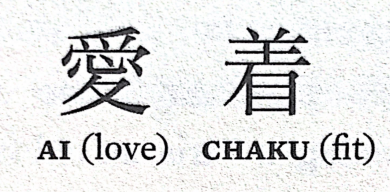

How often do you address your soul? Or the soul an object? Or piece of fruit? Do wood chip remnants have a soul?

There is something to be said about reflecting on the soul of materials that nourish us, provide surfaces for the food we eat and a shelter above our heads. Whether materials are edible or non-edible, animate or inanimate, raw or synthetic, permanent or impermanent, an attitude of animism could provide enormous potential for increasing our respect and care for the materials we use and how we treat them.

Animism is defined as: the attribution of a living soul to plants, inanimate objects, and natural phenomena. It is an ancient belief system prominent in many Indigenous cultures, as well as Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism and Shintoism. Animism is by no means the sole solution to our consumer throw-away culture and environmental crisis. However, the practice of animism could open up conversation and considerations around our approach to design and how we care for objects and materials that allow us to live healthy, safe and creatively fulfilling lives.

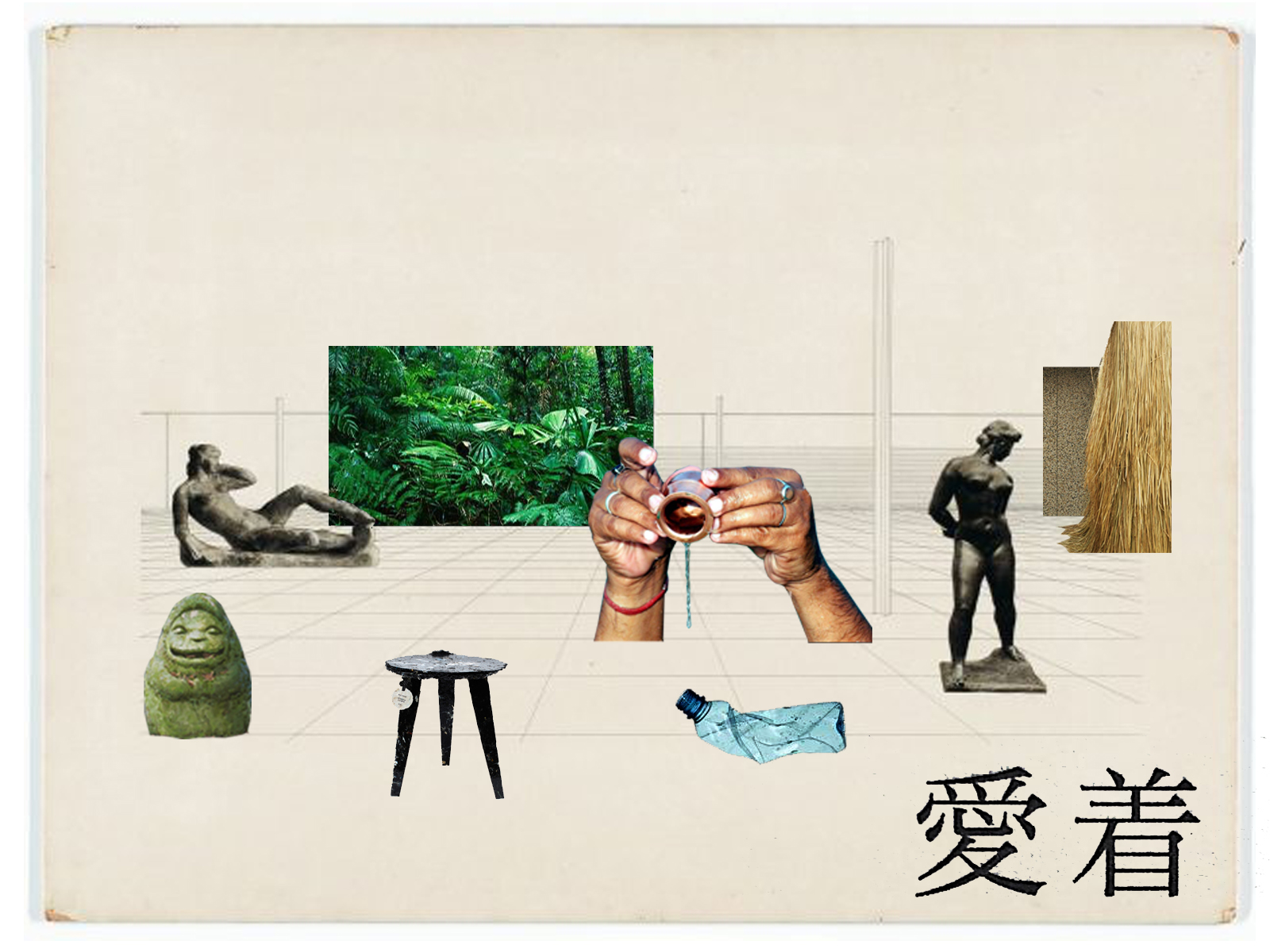

The technologist and designer John Maeda, in his book The Laws of Simplicity explains animism in relation to the Japanese term ‘aichaku’ which is based on caring for an object:

Aichaku (ahy-chaw-koo) is the Japanese term for the sense of attachment one can feel for an object. When written by its own two kanji characters, you can see that the first character means “love” and the second one means “fit.” “Love-fit” describes a deeper kind of emotional attachment that a person can feel for an object. It is a kind of symbiotic love for an object that deserves affection not for what it does, but for what it is. Acknowledging the existence of aichacku in our built environment helps us to aspire to design artifacts that people will feel for, care for, and own for a lifetime.”

John Maeda

Similarly, Robin Wall Kimmerer, botanist, member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation, and author of Gathering Moss and Braiding Sweetgrass, discusses the intelligence of plants in Krista Tippet’s OnBeing Podcast. Kimmerer describes how in the Potawatomi Nation language Anishinaabe mohan, it is impossible to use the term “it” to describe other beings that provide us with sources of nourishment and life. Could we argue that natural phenomena, objects, animate or inanimate, are made up of energies and matter that are beings in their own right?

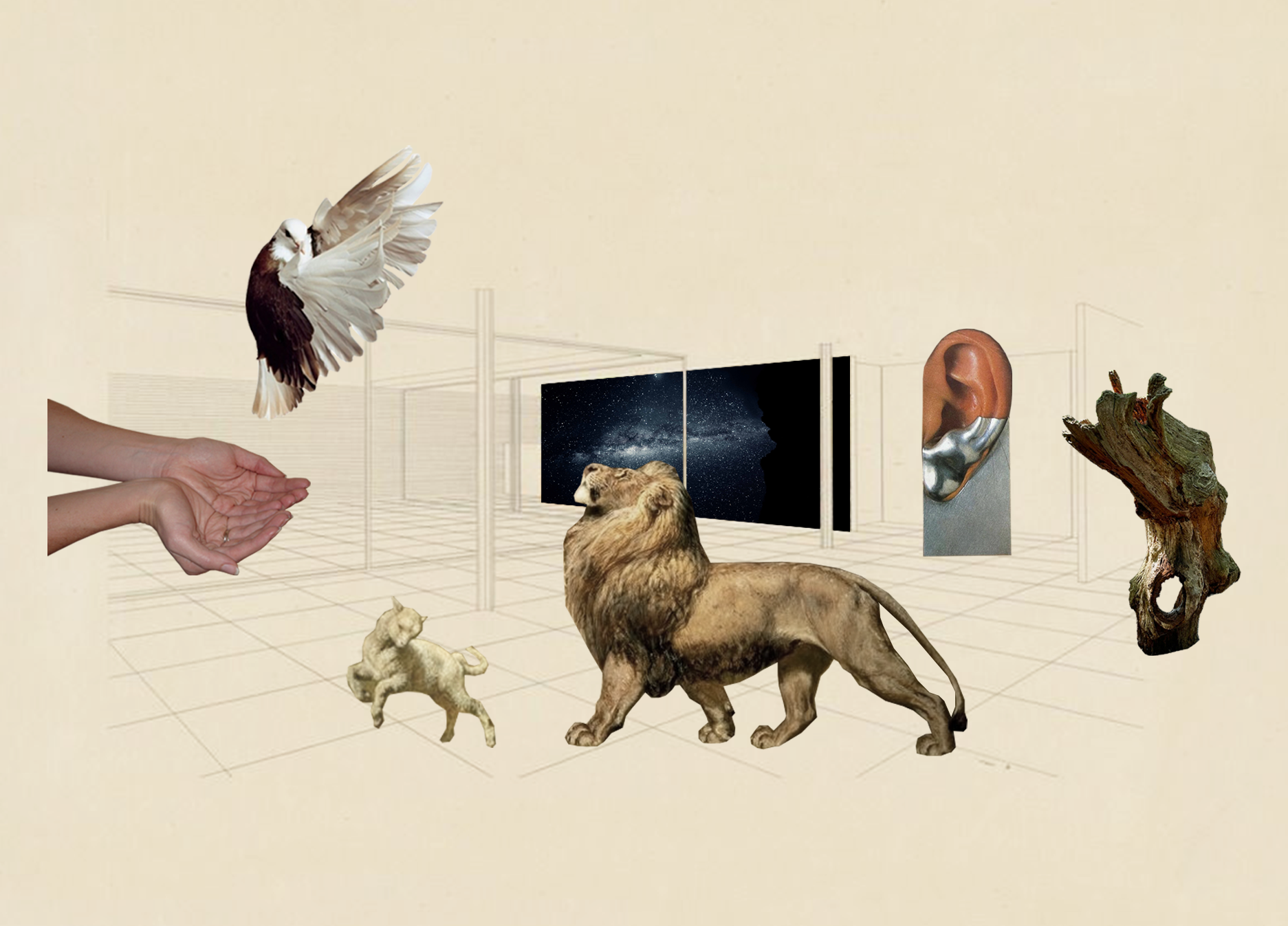

Even so, it is important to note that attributing a soul or spiritual power to natural phenomena does not necessarily guarantee greater care for a certain material or life source.

Take for example, how activist Vimlandu Jha in conversation with Poala Antonelli in MoMA’s Broken Nature podcast, describes how despite the fact that India’s Yamuna river is worshipped as female Goddess Mother Yamuna, she has been abused, abandoned and poisoned for decades, often even in the name of faith. Although animism is a belief that spirits inhabit natural objects or phenomena while religion is the belief in and worship of a supernatural controlling power—especially a personal god or gods—believing in the soul of natural objects can encourage humans to care and protect them to varying degrees. In 2017 the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, considered sacred by more than one billion Indians, became the first non-human entities in India to be granted the same legal rights as living human entities. However as Vimlandu Jha elaborates, despite their legal protection the rivers continue to suffer pollution at the hands of human activity and worship.

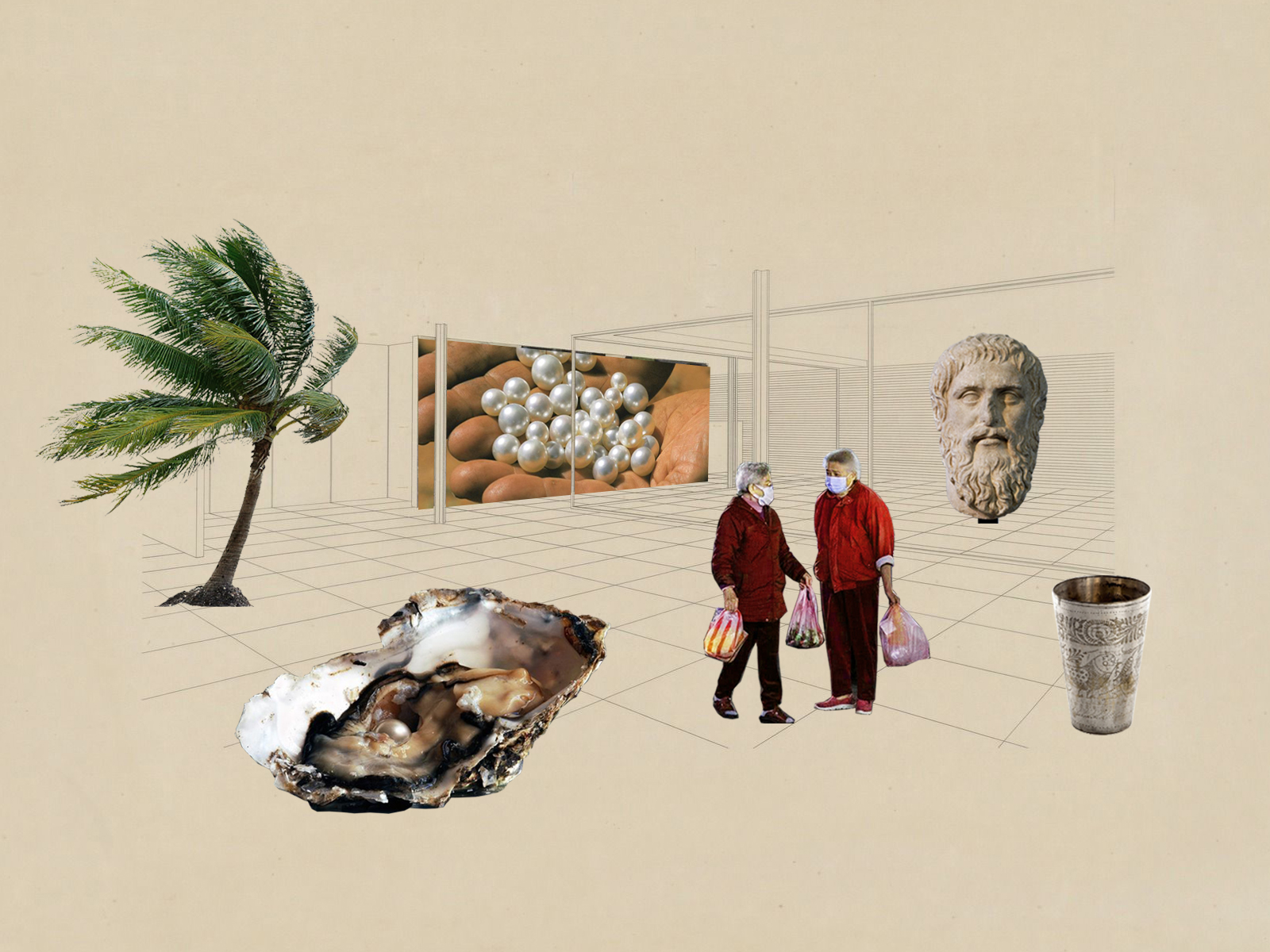

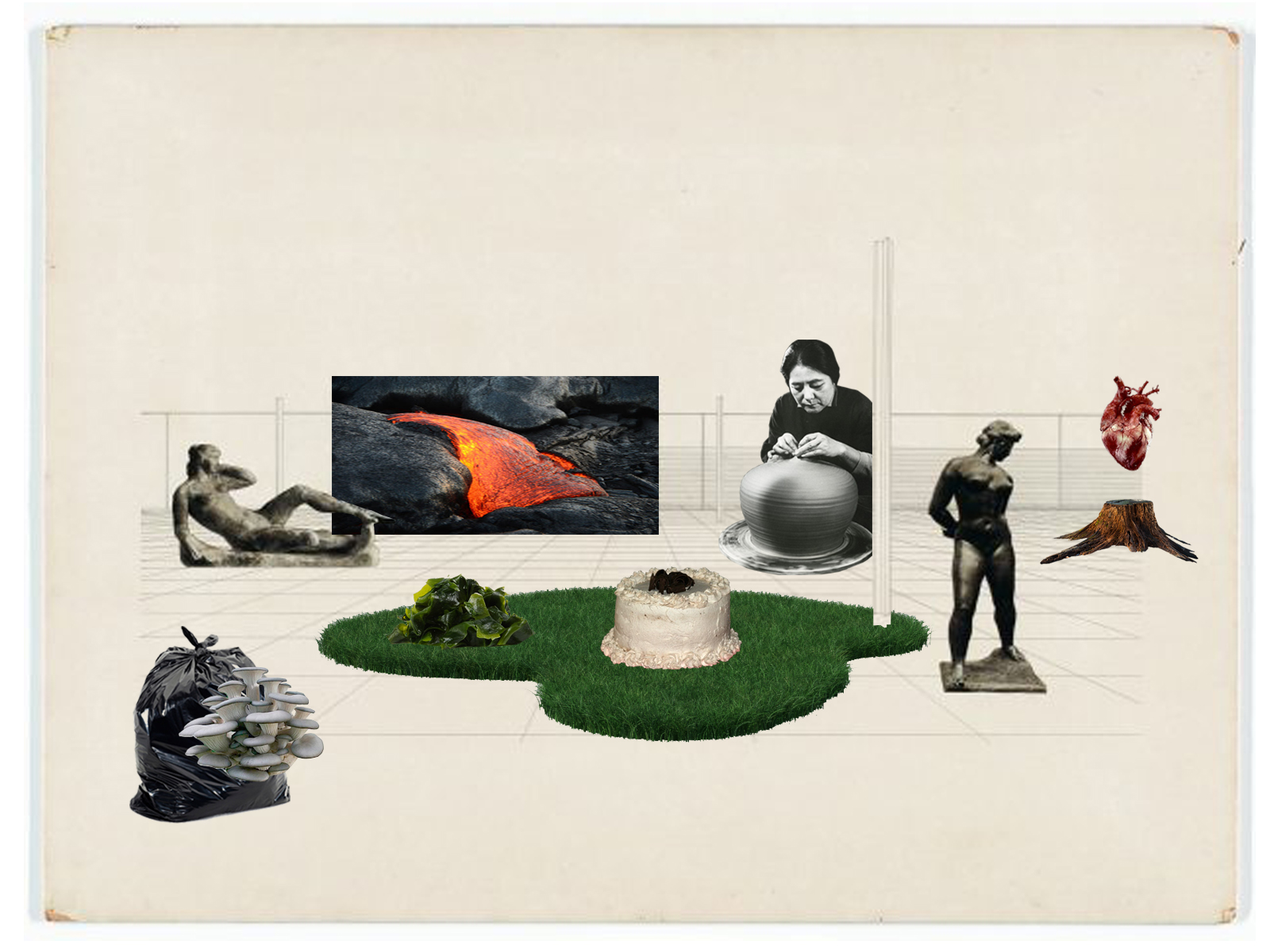

Animism’s effects on behavioural change are unclear and in turn may not guarantee greater care for a life source or object. However, animism in relation to a “love-fit” and a personal relationship that needs to be nourished, has potential to increase our respect and treatment towards the materials we use, how we interact with our day to day objects, and a way of working against our throwaway culture. Creative processes such as ideation, experimentation and interaction are commonly associated with varying degrees of material extraction and waste generation. With this in mind, below are two “what if” scenarios that frame animism’s potential to encourage environmental care and duration in design and purchasing decisions.

Through animism…

…would our design processes be less wasteful?

For example, could we create a world in which the fundamental prototyping process in design education, from architecture to product design, relies primarily on repurposed and recycled materials to improve the integrity and quality of the final project? Architect Barbara Buser may not consider the souls of old sinks and steel beams but is a champion of reusing scrap building material for her buildings. Listen to Buser’s BBC World Service podcast here.

…would we be more inclined to associate quality with regifting previously loved objects instead of relying on buying new ones?

For example, in the aftermath of the Christmas season, could we embrace the attitude of aichaku to create new “love-fits” for family and friends to enjoy previously loved second hand objects? And if all objects were assumed to live a second life, how would that affect the way we design and care for objects?

The above questions, although distinct in nature and scale, present possible applications for animism to increase the value for a previously loved material or object. The trickier part of the argument for animism in light of environmental behavioural change is asking ourselves, where do we draw the line of what is considered reusable, continuously valuable and worthy of long lasting love? Take for instance Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa’s concept of Supernormal, which determines the high value of an object according to our daily dependency on it, to the point that the object subsequently becomes anonymous in its ability to act as an extension of ourselves. This type of long lasting love of an inanimate object does not tap into the conscious effort of animism, but rather a subconscious relationship with the objects we use with effortlessness and ease, day in day out.

- Does an object have to form part of our daily lives to merit long lasting love? Maybe.

- Does plastic packaging embody a soul in the same way an endangered river does? Are they both worthy of the same care? Maybe. Or Perhaps not.

- Should a discarded sink be valued more than a new one? Maybe.

- Can waste material gain new life through beautiful reuse? Yes.

Hayao Miyazaki’s films including the infamous Spirited Away remind us of the power of animistic traditions such as Shintoism. In essence, Miyazaki’s stories show us that the souls and energies that make up our lives do not exist on a separate plane. There is no “other world.” Only this one. So whether or not we believe in the inherent soul of plants, inanimate objects or waste (valuable) material, may we revolutionise how we treat the world around us and what we consider worthy of our care and respect.