A couple of weeks ago, I got to talk with the world’s only Entomophagy anthropologist, Julie Lesnik. This was a huge deal for me – when I started down my edible insect journey, Julie’s episode on the Ologies podcast was one of the first pieces of research I came across and suffice to say, my mind was blown. Here was a person who had spent a considerable amount of their time digging up the past and using insects to decipher and piece together human history—I had so many questions! What could learning about our ancestor’s eating patterns tell me? Are insects and human evolution interlinked at all? I got myself a copy of Julie’s book, Edible Insects and Human Evolution and dove right in. Turns out, A LOT and OH YES.

During our conversation and in Julie’s book, one aspect comes up that I’d like to discuss in particular—the relationship between women and insects. I remember being told the story about how men would go out hunting together to bring food back for everyone, while the women were busy looking after the children. I don’t know about you, but I certainly can’t imagine a group of women not having plan b and c at the ready, in case things didn’t quite go per plan. Something about the story I’d been told suddenly doesn’t seem right.

In her conversation with me, Julie explains:

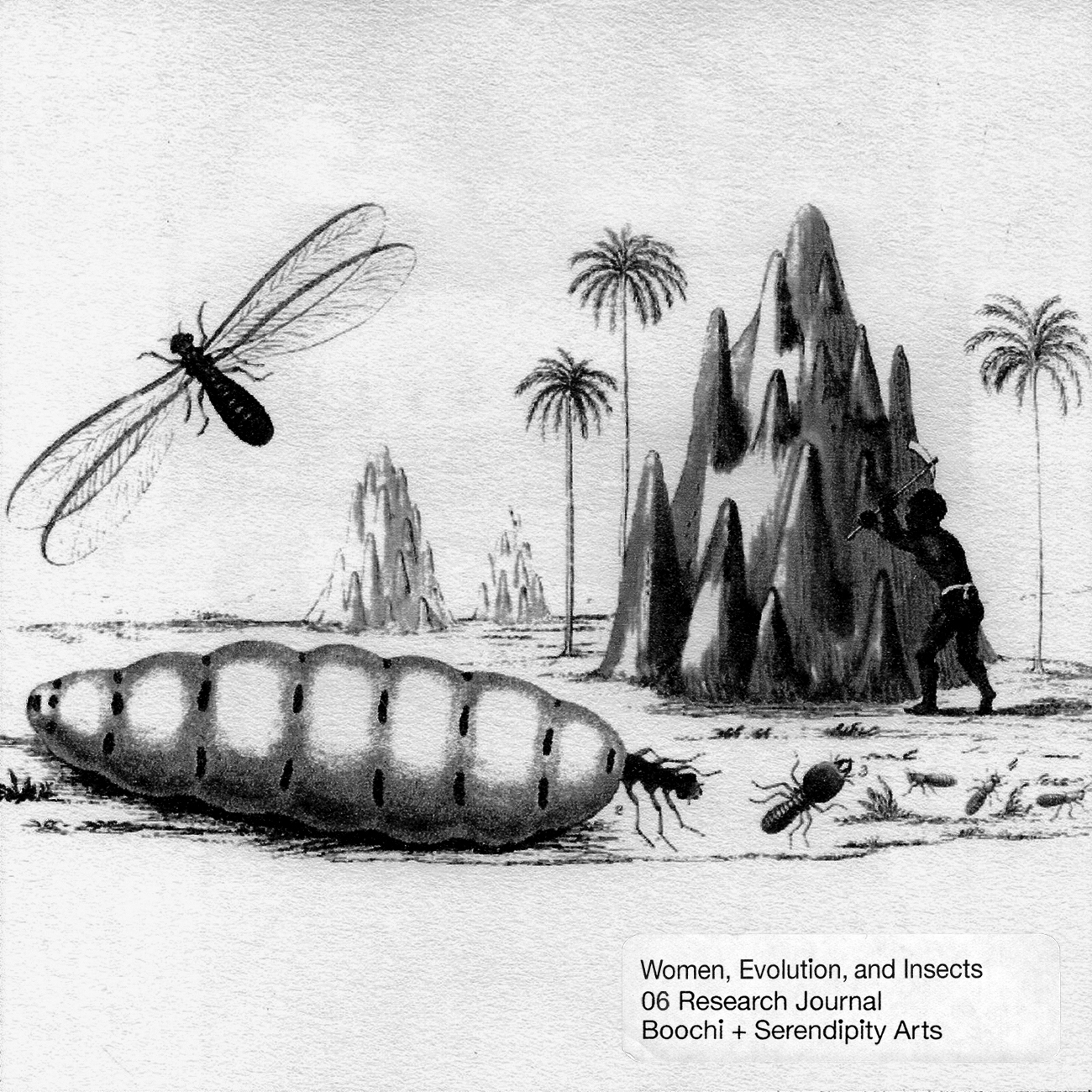

It doesn’t make sense—nutritionally, or going by people’s personality—no one’s just going to sit around and wait for food to come. If you look at foraging groups in the tropics on different continents, any time we have data that shows what the women are gathering, insects are a part of what they’re gathering. From what I can see, in published research when people acknowledge insects as food, you see that the women are gathering them more than the men.

We have this idea that women go gathering, and they bring everything home and share it equally, but when you start actually looking at the accounts from South Africa you see instances where women come across an active termite mound that they gather and bring home to cook, but also you see that they sit around, socialise and eat those termites until they’ve had their fill. This shows us that while insects are a part of men and women’s diet, women are consuming and relying on the insects more.

In the chapter “Nutrition and Reproductive Ecology” of Edible Insects and Human Evolution, Lesnik goes into more detail:

Relying on the capture of large game is a risky way to meet dietary demands, especially when many of the same benefits can be received from visiting a termite nest for a short period of time. Insects thus provide an appealing resource option for individuals who cannot afford to take risks in how they procure food. Although some hominin individuals may not have been affected when they had to endure short periods without game, female hominins, who for much of their adult lives were responsible for meeting their own nutritional demands plus the needs of a gestating foetus or nursing infant, would have benefited the most from the dependability of insect foods.

Hearing Julie speak about the relationship between women and insects, I started thinking about how this information would have been passed down. If insects were so nutritionally significant to ensure optimal health of women and their infants, it seems to me like women have been the secret keepers of this knowledge, and have passed it down to a long line of women. It makes me wonder how many contributions made by women have been ignored, or misread to be a man’s contribution. I continue to be baffled by this, but primarily, I am in awe of women’s resourcefulness since the beginning of time and their intuitive ability to harness their ecosystem to provide for their health.

Boochi and its learnings have been initiated at and facilitated by the Serendipity Arts Residency Food Lab.