In 2018, I worked at a permaculture food forest in Goa, India where I learnt how to grow food using regenerative and resilient systems of design. One morning, we found an army of weaver ants taking over a cacao fruit that we wanted to harvest for ourselves. As a means of integrated pest management, we cut the ant nest down into a garbage bag, ran with the bag to the kitchen while trying not to get bitten, and threw the whole thing into the freezer. In a couple of hours we ate the whole lot of them. As we dipped ants in chocolate and blended some with chilli, salt and shredded coconut I wondered why I didn’t eat more insects regularly. Who actually eats insects in India today? Which ones do they eat? How do they harvest them? Where do they find them?

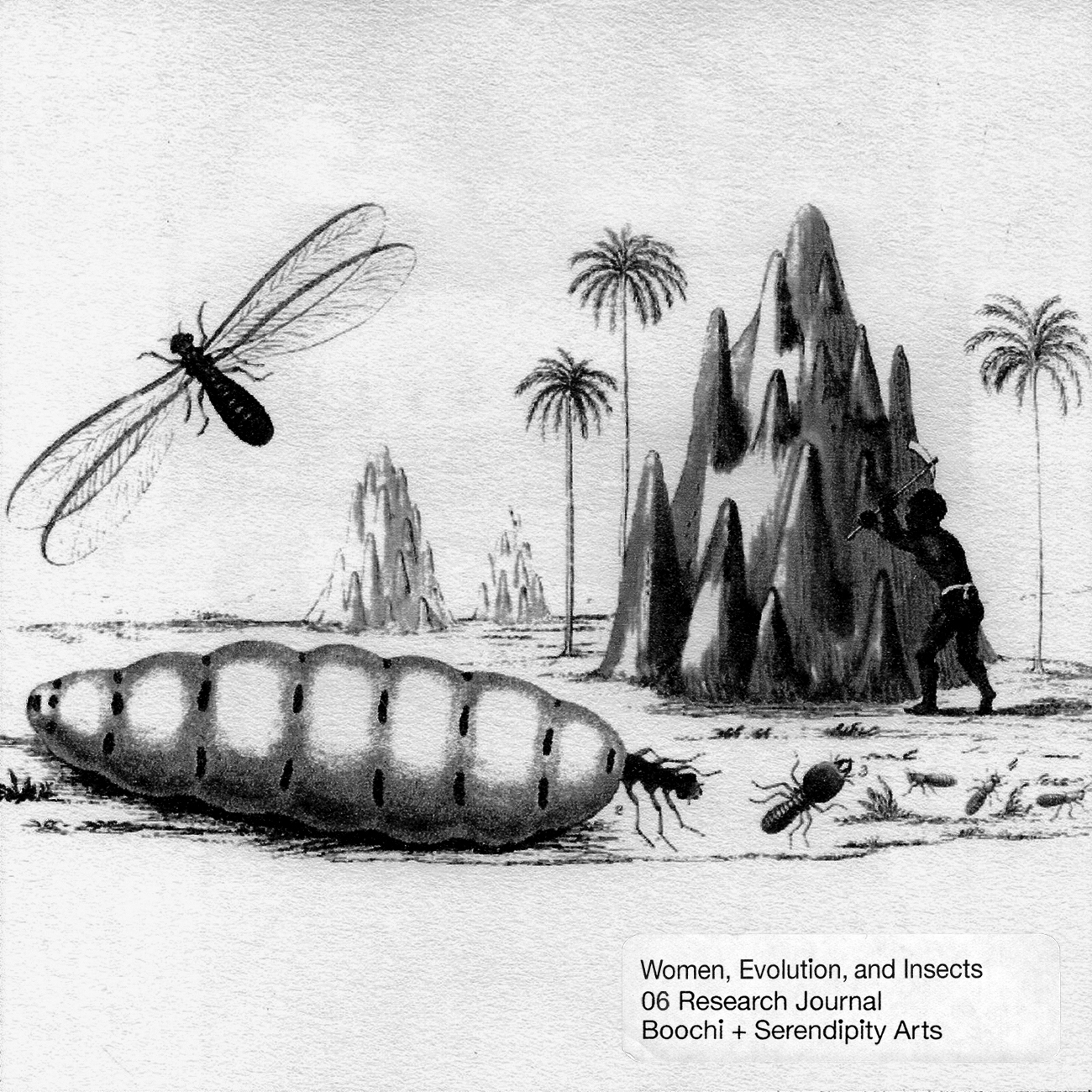

Insects are a part of over 2 billion people’s diet globally, and India has an exceptionally rich heritage of entomophagy, the practice of eating insects. As I began to do my research, I found that the communities across the country that still eat insects are typically historically excluded, with their culture and traditions on the margins of the majoritarian national identity.

The seasonal fluctuations of temperate regions made meat the prominent source of protein, and with each passing generation, people in these regions ate less and less insects until they vanished from their plates and culture entirely. When European colonists came to the tropics and saw indigenous people eat insects, they likened them to beasts and savages who ate food unfit for human beings. By othering the indegenous population, it became possible for the colonists to indenture the local people and treat them like beasts for colonial gain. India also had its own prejudice hierarchy in the form of the caste system that existed long before colonial rule, where the aspiration was to live a “bramanical”, essentially vegetarian lifestyle was enforced.

Under both these circumstances, the position of power was held by people other than small tribal communities. Today, as India rapidly urbanizes and westernizes itself, the tribal communities are the only ones who have held onto their culture and traditions. Urban upper caste India continues to view their practices as backward, savage and “lesser” than their own ways. Tribal communities have been grossly neglected and under-represented in the national socio-political sphere, and continue to be “othered” even today.

I didn’t realize how opaque the colonial and casteist lens across our eyes is when we think of our food, especially my own. What would a decolonised, de-stigmatised diet taste like, and what might that mean for us, our food and our ecosystem? The UN FAO’s report on Edible Insects and Food Security says that by 2050 there will be 9 billion people on this planet, and not enough land to produce the food needed to feed them all if we continue to practice agriculture the way we do today. It identifies insects as a very real future food, delivering nutrition and security to communities across the world.

Today, as a resident of the Serendipity Art Foundation’s Food Lab 2021, I get to explore where India is with insects on our plates through my project Boochi (which is a word in Kannada used to describe all crawly things to children). Over the next two months, I hope to:

- Collect and archive insect recipes from different communities across the country, and decode them to arrive at sustainability metrics of eating the insect

- Record the experiences of 20 people who will be tasked to cook with a fermented ant amino sauce

- Interview and engage with entomologists, chefs, anthropologists and innovators alike to gauge the landscape of entomophagy in India, and map its trajectory into the future.

Recipes are treasure troves of hidden information – they inform us of taste preferences, seasonality, superstitions, processes, specialised equipment born out of necessity and innovation, the cost of ingredients and perhaps even its journey through the supply chain. By archiving these recipes at the core of my project, I hope to understand the contexts in which communities eat insects, and apply this information to design smarter food systems for the future.

This is the starting point of my quest to discover what our future might taste like.

Boochi and its learnings have been initiated at and facilitated by the Serendipity Arts Residency Food Lab.