This story is a part of MOLD’s series on Decentralized Design. Through this series of conversations we explore how designers, thinkers, and artists are using decentralized approaches to seed a more resilient future.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, or so they say. Perhaps a more accurate, amended version of this adage would be that imitation is the most expedient way to secure a profit. As landlords and restaurateurs carefully tailor dining experiences to the tastes of the anonymous median customer, actual diners are seeing carbon copies of the same restaurants — same food, same decor, same graphic design— pop up across city centers. In a round table discussion between food writers Jonathan Nunn and Isaac Rangaswami we discuss this troubling trend of homogeneity, diving into the relationship between food and place and examining food’s role in facilitating dynamic, community-specific spaces. Jonathan Nunn is a writer and editor of the expansive food publication Vittles and most recently edited London Feeds Itself, a collection of essays that map the city’s numerous food architectures and cultures. Isaac Rangaswami is the writer and documentarian behind the prolific Instagram account @caffs_not_cafes which has become a living archive of sorts for London’s traditional caff culture. We speak about the relationship between food writing and gentrification, the merits of lingering, and how rising rents might be eroding the flavors that have defined London’s rich culinary landscape.

Isabel Ling:

Tell me a bit about yourselves. How did the both of you begin writing about food?

Isaac Rangaswami:

For me, it all started with walking. I find it very relaxing and for years I’ve spent my Saturday mornings walking for three or four hours around different parts of London. Usually I structure those walks by identifying a few old buildings I want to look at. Over time, I became interested in old eating places too, specifically really ancient caffs. I like old caffs because they’re so inexpensive and atmospheric, like canteens, or diners in America. London used to have loads of really old ones, many of which were opened by Italian people after the war. At first, I was drawn to them because I found their ageing interiors and signs so interesting. But after I’d visited loads of them and realised there were more left than I thought, I became passionate about showcasing them online, to get other people to go to them.

I don’t really see myself as a food writer. But I’ve been a copywriter for almost 10 years, working mainly for software companies, so that’s how I’ve learned to write. But more recently, I’ve been thrilled to be doing a lot of restaurant writing off the back of my Instagram.

Jonathan Nunn:

Me and Isaac have pretty much the same villain origin story. I started out walking too, usually with no real purpose in mind except to be alone. I went to the country’s most boring campus university and I didn’t enjoy my maths degree or my time there, so I came back to London feeling really depressed about having nothing to show for it but also wanting to throw myself back into the city. How I dealt with both of those things was to go on long, aimless walks at night, and I would eat on the way to break them up, mainly in Green Lanes or Chinatown. Actually, the first food piece I wrote was about Green Lanes, and I purposely structured it as a walk from one end to the other, which then got messed up by Eater’s map algorithm. I emailed my editor to ask that it get changed back to the order I wrote it – which looking back seems fairly ballsy for a first-time writer! But I’ve never been able to separate my writing from the experience of walking there, which is true for I think both me and Isaac. We are as interested in what surrounds the restaurant and how we got there, as much as the food. More and more I feel I want to write about the journey and never quite get to the destination – the journey is always the important bit!

IL:

I’m interested in the format of walking, because it feels like a very specific way of interacting with the built environment that opens up a new way of noticing. When you are on these walks, what draws your interest as an eater?

IR:

Signage has been a big thing for me for a while. I find it really fascinating and compelling when you come across a historical-looking sign, which makes me curious about what other old stuff might be inside. With a lot of caffs you can immediately get an impression of how old the place is, if it’s got a hand-painted sign, for example. It’s the same with Victorian and Georgian buildings, which you can try to spot based on their brickwork, or windows, or the kind of doorbells they have — there’s all these different visual clues.

IL:

Do you see any patterns between these architectural signifiers with the food or quality of food inside?

IR:

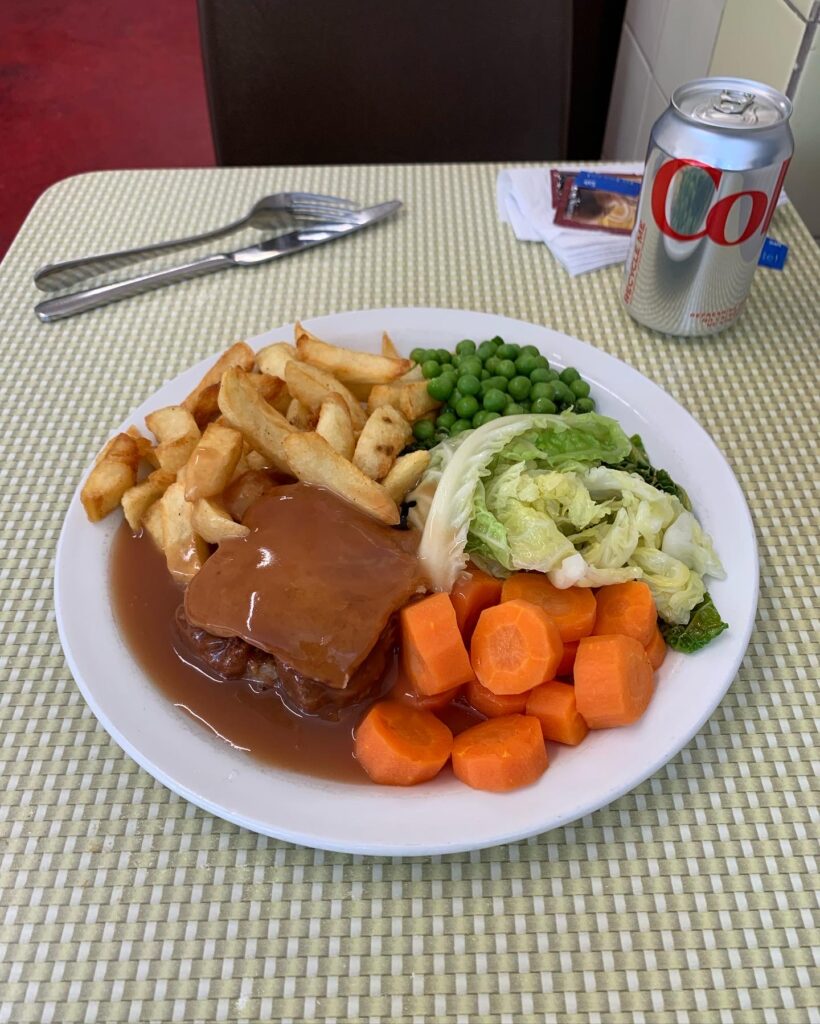

Not necessarily, as the caff could have changed a lot since its sign or other parts of its exterior were made. And to be honest, the quality of the food isn’t even my primary interest, as the food these places serve is so inexpensive and can be processed, like white bread and canned beans. I don’t think it’s fair to criticize food like that, because it’s so affordable and basic, in a good way. A lot of people love it, I like it too.

The main thing that interests me about old caffs is how they serve as shelter. Rather than a chain restaurant where somebody might move you along after like an hour and a half, in somewhere like this you could spend less than a pound on a cup of tea and then use the space in the same way you might use a public library or a bus stop. There’s a spot near where I used to live in Camberwell in south London that really got me interested in caffs, called Rock Steady Eddie’s. Inside there’s a painting of the place by an artist called Ed Gray, which has this great detail of a guy asleep with his head resting on his hand and a bottle of booze tucked into his jacket pocket. In the painting there’s also a student-looking guy eating a fry-up and a couple kissing in the corner. If you go inside today, it’s the same crowd; it’s a place where people are free to sit down for as long as they like, like a public space.

JN:

I think we’re both interested in spaces where you can linger, specifically those semi-public spaces where this loitering is possible and encouraged. The ability to loiter is very important in building a sense of belonging and security in a city, and these spaces are dying out. There’s definitely an equivalence between [Isaac’s documentation] of caffs and how I write about restaurants, and a big part of it lies in wanting to convey the pleasure of just being there, when you sit in that space, without much pressure to spend money or consume.

The enemy of resiliency is homogeneity. What is true for crops is the same for cities.

IL:

Both of your work highlights restaurants and food vendors that food media tend to overlook. What about creating this sort of representation is important to you?

IR:

[With @caffs_not_cafes] I wanted to try to draw attention to things that I thought were beautiful, but I know might be ordinary or mundane in a lot of people’s eyes. Caffs can often be historical and filled with these gorgeous, ornately decorated features, so I’ve always been interested in showcasing those details, which some people might miss. I really started off by wanting to preserve caffs and get people to go to these places, since they’re so under threat. There’s a handful of famous old caffs in London, like Regency Cafe and E Pellici, that have huge queues outside their doors every Saturday, which is brilliant. When I started the page, I wanted to highlight old eating places that don’t get that same attention or level of footfall, which are often just as pretty and interesting, like Scotti’s Snack Bar in Clerkenwell, River Cafe in Fulham and Mario’s in Kentish Town.

Of course, I suppose I am lucky that I feel so comfortable just walking into these places. My younger sister was telling me that she probably wouldn’t want to go into a lot of the caffs I write about, because she sees them as being like old pubs and full of men, which I appreciate can be the case. So I guess I’m also trying to reorient how people might look at these spaces, to show how welcoming they can be and that they’re historically interesting, like museums.

JN:

At the moment, you have hundreds of writers, chefs and PRs whose job is saying exactly the same thing: that London’s food is great and this is good for London. And I think there’s some value in someone whispering ‘but it could be better…’ Also, ‘is it really good for all of London?’ Because I think it’s important to note that the abundance of high-end restaurants in London aren’t accessible to everyone, and isn’t how most people eat. They’re also very much part of the same force that also keeps rents high and makes housing unaffordable to most people in the city. Obviously they’re not the same thing at all, but the same force drives both of them, and it’s worth asking who this narrative ultimately serves. The big thing here is the property market: because rent in central London is so insane, everything must be marketed towards the tastes of the median customer, which is such a homogenising force. So I try to write about other places and other forms of taste and design, not because they’re inherently better and these other restaurants are all bad, but to make the case for what food writer Riaz Phillips calls “a diversity of diversities”.

Weirdly, as London has become more diverse and as restaurants have also become more diverse, media representations of both London and those restaurants have become narrower and narrower. I don’t really see my city in those representations. It seems counterintuitive, but I think part of it is because in the 80’s and 90’s you had fewer restaurants opening each week, so if you were a critic or food writer you really had to do your research. You had to walk, essentially. Actually if you go back and look at those 90s reviews, they cover a real spread of London in a way that doesn’t happen now. For example Vrisaki, this Cypriot restaurant I grew up near — if you go in today they still have these national newspaper reviews and Evening Standard awards from the 90s on their walls, along with the bad celeb pics of Anthony Costa from Blue. That was a Zone 4 community spot that blew up and became a part of London’s mythology. I’m not sure that would happen today.

IL:

Are there any specific audiences you find yourself writing for?

IR:

When I’d share something, sometimes I’d check to see if Jonathan had written about that specific place before and choose somewhere else if he had. But that was way too hard and Jonathan and loads of other people probably already knew about them anyway; I now think that multiple people writing about the same place is a positive thing, as we all have different perspectives. So while I do try to draw attention to less well-known places, over time I’ve also seen the value in sending people back to places they already know and love.

Recently I’ve been trying to highlight caffs and other eating places in central London, many of which are probably actually suffering the most because fewer people are working in offices now, so they’re getting a lot less footfall as people spend more time near where they live. I’ve been going to Scotti’s in Clerkenwell a lot lately, for that reason. When I post about somewhere like that, often I’ll see people commenting saying stuff like, “I haven’t been there in years, I didn’t know they were still open! I’m going to stop by today”. So that’s really encouraging.

JN:

There’s a kind of tension between writing for people who already innately know that a restaurant is important, and writing for people who want to find restaurants that they don’t know about. It’s the same tension between who your audience is and who you’re really trying to write for. I think maybe Isaac’s audience skews more towards people who already know these caffs and just want to see them being written about, which is lovely. There’s that tweet ‘Men are happy sitting around for hours naming old football players’ – it’s like that, but people are just delighted to hear old caffs they know get shout outs! And my audience, if I’m being realistic about it, probably skews more towards people who want to find things.

I think both audiences are valuable, but you have to be intentional about who you really want your audience to be for a particular piece of writing. I know when an article of mine has been written with the care and research that it needed to have if it reaches the community who know the restaurant and they recognise it as truthful without being overly romantic or fetishistic. For me the best reaction is when people are like “Yes! This was an iconic place from my childhood” or “My cousin owns that restaurant” or just delight that it’s been recognised, because it then places these restaurants within a communal history of London rather than something I’ve ‘discovered’. That’s why the restaurant guide I’m most proud of is the Peckham guide for Eater. It found the audience I wrote it for – people who actually grew up in Peckham – and it lives or dies on that reaction. With Vittles, I’m very aware that my articles are now behind a paywall, and that means our audience is largely made up of people who can afford a paywall. That is a big source of anxiety for me because it shuts out a lot of the audience I want to write for.

IR:

This makes me think of something you said to me recently Jonathan, where I was telling you that sometimes I’ll go to a restaurant and I don’t write about it, because I’m worried that it’s not my place to. Like if it’s busy enough as it is with the people who already go there. And you said that sometimes you’ll just go up to the owner and ask, like “Would you mind if I wrote about this on the internet?”. Which really seems like the best solution to some of that tension.

JN:

I don’t think a single restaurant owner I’ve ever asked has ever said no to being written about or cared that a few more people outside of their regular customers have come in.

IL:

Yeah, do you ever find yourself gatekeeping when it comes to these places that you write about?

IR:

Generally no, because I feel like a lot of the caffs I’m writing about are already on their knees, so I feel like additional customers won’t hurt. One of my main objectives is to celebrate these places, to get people to go to them. I appreciate it can be more complicated than that though, depending on the restaurant and its existing customer base. I’m increasingly writing about a lot of places that aren’t caffs at all, so I try to be sensitive to what the impact of me sharing that place might be, which I’m thinking about more as my audience has grown.

JN:

The gatekeeping that goes on with people’s favourite spots can be completely counterproductive. Isaac, you mentioned Scotti’s – someone had a go at me recently for sending new people there who all ordered the same sandwich. It’s annoying for a day maybe, but if that doesn’t happen then it’s just going to die unfortunately and we’re stuck with bad escalope sandwiches.

I only gatekeep during the process of writing because I want to make sure what I say is watertight before sending someone there. But there’s an equal responsibility to the restaurant, and the community who uses it, as much as the reader. Restaurant writing is basically travel writing in miniature and it comes with all the same pitfalls, so you have to be very careful about how you write about places and who you’re telling to come and what they’re going to expect. I don’t exist outside of these ripples of hype and influence that I criticise, so something that I’ve had to think about more often as my audience has grown is that through writing you can change a place in unexpected ways. You can never predict what it might set in motion, or how that writing might be co-opted – one day you can write about a place, and the next the article is being used by Foxtons’ to sell houses! I called this phenomenon ‘Schrodinger’s chaat’ – it’s like the restaurant exists in a quantum state before the moment you publish.

There are also places I’ve purposely not written about or not written about excessively because it can be a very blurry line between public and private. Like there are times where I have to think: what is this place? Is it a men’s club? Are they trying not to be found? Even though it’s technically public, is it actually a more private spot for a specific community? For example, there’s this pub serving Ghanaian food I’ve recently learnt about, and they only serve one thing: grilled fish. The problem is that they’re hilariously understaffed for how many people go there, and the fish often takes 2-3 hours to come out. Their Google Review page is already full of people who are absolutely livid, leaving two star reviews because of the wait, and still saying ‘but the fish is really really good.’ Now, I’m going to go because I’m obsessed with the idea of this fish being so good that masochists are willing to put themselves through the experience, but then I do have the conundrum of whether it should be written about, and if writing about it would contribute to the frustration of the new customers, old customers and the people cooking. There are some times when the answer to ‘Should I write about this place?’ is ‘no’, or at least, ‘with some caution’. I try to say that if there are certain things that are important to your restaurant experience then do not come, because you won’t find them. Actually, it’s as important to say who the restaurant is not for as much as who it is for.

IL:

It seems that change and disappearance are factors for both of you in terms of what you choose to document and how you document. I’m wondering if you see yourselves as archivists at all?

IR:

I was definitely drawn to documenting caffs because of preservation, but I try not to be too sentimental about it. A lot of people will lament, like, “Oh we’ve lost all the caffs”, but then don’t actually go to the ones that are still around. And it’s the same all over the world — in New York, some people talk about the loss of that city’s iconic historical eating places, without necessarily frequenting the many old places that are still there, which may be hanging on by a thread.

So I guess I want to promote the idea of actually supporting these places while they exist, instead of mourning the ones that have sadly passed on, since there’s still loads left. I like approaching it less in terms of archiving or preserving, but instead normalizing spending your spare time in places like this and making it a part of your daily life, because otherwise they’ll die out.

JN:

Yeah, I didn’t initially see archiving as my role but more and more I find that’s exactly what’s happening. One of the first big writing projects I did was about Elephant Castle, which was based around the imminent demolition of the shopping center that is now gone. So if you read that piece now, it is basically an archive of various businesses as they existed in 2019. I’m often quite pessimistic about the change that writing can enact, because no amount of writing was going to save that shopping center against much more powerful forces. But at the very least it is an archive of what has been lost, and maybe it can inspire someone who is reading to think differently or be more proactive about the things they love in their area.

This goes back to how to write about restaurants while being scared you might change them. This is why I’ve moved from being very specific about restaurants I recommend and making it easy to locate those recommendations in one place, to being a little more vague. I’d rather try to shift what we perceive as being valuable or ‘good taste’, which then gives the reader some agency and allows them to take that lesson into their own neighbourhoods. I think at its worst, restaurant and food writing sells culture to an audience who only wants to consume and commodify it, but at its best I think it can encourage some kind of stewardship over food spaces. Hopefully this attitude of stewardship rather than ownership can help in actually preserving them.

IL:

Right, you both find ties between food and the architectures that house them. What are some of the things you’ve discovered in writing through this lens?

JN:

I would say the more I write about food and restaurants, the more I realize that everything is about land. You can tie every single thing I’ve ever written about restaurants back to rent and property development, maybe even more so than immigration. I’ve recently learned, Isaac, that a lot of the British-Italian caffs have managed to stay where they are for so long because they had the foresight to purchase the freeholds to the buildings they are in.

IR:

Right, that would make sense as to how they were able to survive the pandemic, too.

JN:

Yeah, and actually, I think a lot of the places I think are interesting in London – even the more high end places – have unique rent situations, and that allows them to be more generous and less in thrall to the median customer. I feel that as rent exerts this outward pressure on restaurants in London, the places where more interesting things are happening in terms of food have become more unexpected. For example, Park Royal, which is this industrial estate in West London that has become home to Lebanese, Syrian and Iraqi food businesses, is more alive than Edgware Road right now – because you can rent a warehouse there for the same price as a hole in the wall in Marylebone. Or Burgess Park, which is written about in London Feeds Itself, had a more interesting barbeque culture than any restaurant that spent money trying to badly recreate American southern BBQ in the 2010s. In some sense, it feels like you’re not in London there, but at the same time this exact nexus of Caribbean, West African, and Latin American communities could only exist in this artificial suburban south London park. That feeling of not being London, but actually being entirely London, is something I’m constantly looking for.

I went to Nine Elms the other day, which is one of the most straightforwardly evil parts of London, with these buildings that look like cancerous tumors. Most people were visiting the new Battersea Power Station which has been turned into this huge brick Westfield, and it has all the same food businesses you can find in any other development. But on the other side of the tracks there’s a car boot sale, and among these shambolic three to four hundred businesses, which range from legitimate to criminal enterprises, you’ve got food stalls. And there is nothing there for the median customer. There are Romanian workers coming from all over London to be there and eat barbecue, loads of young Brazilians having pasteles and sugar cane juice, Caribbean cooking on drums, funnel cakes over coals. No London street food market could ever purposely curate this mixture of businesses or people that come together naturally. How often do you come across spaces in London which are as well-used as that?

IR:

Yeah, it’s really about use. You mentioned those British Italian caffs, which haven’t changed for decades and that’s why I find them so beautiful. But I am increasingly aware that I shouldn’t only focus on those caffs, just because they’re so historical and I’ve personally found them more architecturally interesting. Lately I’ve been getting more into caffs which are a lot more plasticky and modern, the types of caffs that were built in the 80s and 90s.

I’d never really thought to write about them until recently, but now I realise these newer caffs are just as important a lot of the time and sometimes way more well-used. I guess they’re less under threat as a result too. There’s this enormous modern caff in Woolwich called First Choice Cafe, that’s like this mega caff with a hundred seats. Chef’s Treat in Lewisham is similar. These are local landmarks that people flock to in certain areas, where they’re one of the few non-chain restaurants on their high street. So I’m starting to realize that with so much of my focus on what I find beautiful about old caffs, it can come at the expense of emphasizing their community function. So I always try to come back to how these places serve as community gathering places, or just spaces where people can sit down for a while, without spending loads of money.

IL:

What does a resilient urban food system look like to you?

IR:

I’m really interested in the provision of inexpensive restaurants, where ordinary people can get something affordable to eat while they’re out and about. I was still a kid when a lot of the really historical caffs were wiped out in the early 2000s, so I didn’t really notice happening. But now I realise what replaced them were coffeehouse chains, like Pret and Costa, which I don’t think are fundamentally bad, just identical and slightly more expensive than they need to be.

A lot of my generation grew up eating in places like those. I find it really interesting that there’s this alternative that was here before, in restaurants that are even more affordable, sometimes way prettier inside and often family-run, where the owners greet customers by name and you can sit down for longer without being moved along. I’d love to see a system where these places continue to survive, so ordinary people have more options. I think a big part of it is being able to eat somewhere more interesting too, where you don’t have to spend much and you know that your money is going to a small business, rather than an enormous, ubiquitous one.

JN:

I think the enemy of resiliency is homogeneity. What is true for crops is the same for cities. In agriculture, homogeneous monocultures make crops susceptible to disease, and when one is infected, they all get wiped out. And I think what we need in a city is real heterogeneity and what resilient urban food systems look like for me, would be a true reflection of the people using it and running it. One question I would love to ask every restaurant owner in London is not necessarily ‘are you proud of your restaurant?’, because I think most people would say yes, they are. But I’d like to ask them, if you are being honest with yourself, are you serving the type of food you really want to? And I suspect that most people would say no. Because London doesn’t allow for it, there’s too much external pressure to stay viable. So I think what resiliency looks like to me, is for food to truly reflect the desires of the people who run them and of Londoners.