Subject to Change is a series about the anarchitecture of New York City foodscapes and the makers that are designing new ways of working.

Cooperative Economics 101, a free Zoom workshop coordinated by the Food Issues Group, references the studies of economist Dr. Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, a founding member of the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives and author of Collective Courage: A History of Cooperative African American Thought and Practice.

“African Americans started using cooperative economics from the moment they were forcibly brought to the Americas from Africa, at first for practical reasons. They realized that their survival depended on working together and sharing resources. They had collective traditions from the African nations and civilizations they come from, that they applied in the Americas when they could,” said Dr. Gordon-Nembhard in an interview with Shareable in 2014.

In their opening for the workshop, Ora Wise, of the Food Issues Group, offered context for why cooperative economics is a critical principle to employ at this moment. The historical confluence of a global pandemic and the Movement for Black Lives must be leveraged for necessary systemic change and a radical redistribution of resources within the food industry and beyond. Wise, alongside other facilitators on the call, has been organizing within FIG since 2015 around sustainability and equity in the hospitality and food industry, and has been providing food relief to four New York City boroughs since the pandemic began.

“Now, in this Black-led movement for reparations and accountability for hundreds of years of land-theft, genocide, enslavement, and coercive labor structures, we know that the changes we are going to effect are not going to be big enough or deep enough in the current industry. So, collective ownership, cooperative economics, and community control are necessary for rebuilding and transforming our food system to be a part of the [environmental, political, ethical, and financial] solutions that are being called for,” Wise explains.

In this moment where interlocking systems of oppression can no longer be ignored, and structural change is required, community members are organizing and sharing resources. About 100 attendees tuned in for a facilitated discussion on how to employ cooperative frameworks and horizontal relationships of solidarity and mutual aid in businesses and community spaces. Esteban Kelly, the Executive Director for the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives, co-founder of AORTA (Anti-Oppression and Resource Training Alliance), and co-founder of the Food Justice and Anti-Racism working group at Mariposa Food Co-op began the meeting with this acknowledgement:

“Transforming our food system and building up a solidarity economy is part and parcel of the freedom and liberation of Black and Brown people and Indiginous people and everyone who works the land,” says Kelly who has also been a policy advisor for the Movement for Black Lives.

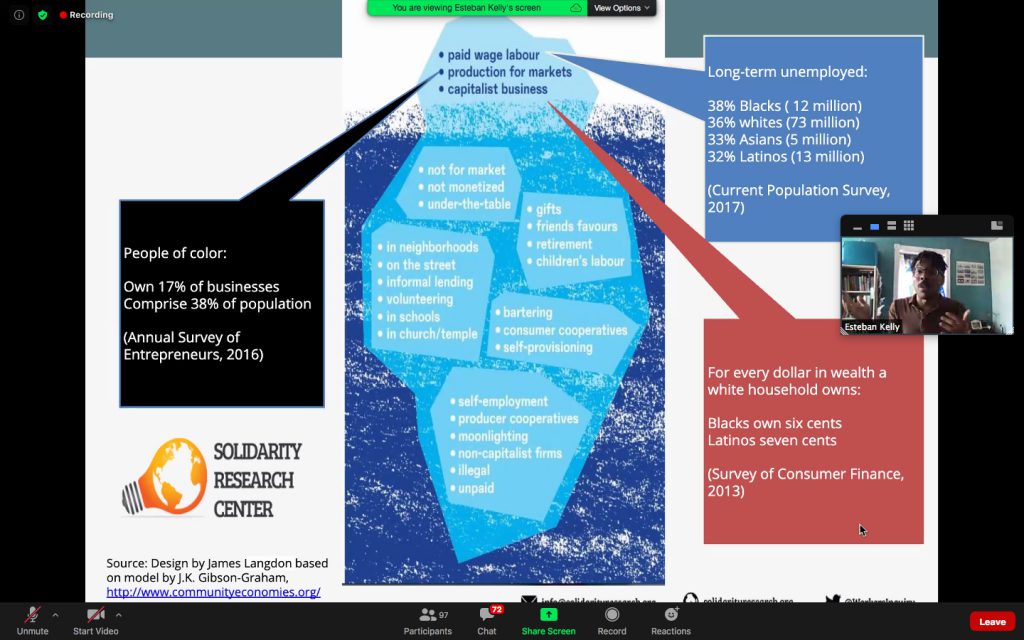

As organizing language floods our media feeds, Kelly expands upon what words like divestment, solidarity, and reparations mean in practice through Cooperative Economics. Understanding the current capitalist economy (top of the iceberg) helps us understand the vast, racialized wealth gap that a linear and extractive economy perpetuates, and the unaddressed ancillary components that are necessary for survival (bottom of the iceberg). In order to divest from these exploitative structures, there must be a reinvestment in projects that increase access to capital such as a Solidarity Economy and Worker Ownership. This means investing in shared prosperity, minimizing risk, and expanding democracy across race and class lines in order to build the foundation for a regenerative food economy.

The Solidarity Economy puts people and the planet before private profits and power, and seeks to supplement globalization with community-based social safety nets. Worker control, collective ownership, and democratic decision-making structures are the foundation of the Solidarity Economy. Health, food, water, shelter, education, community, and energy are at the center of the Solidarity Economy as areas that need to be continuously replenished. These foundational components drive creation, production, exchange, consumption, and surplus allocation, and need continued reinvestment in, in order to sustain the Solidarity Economy cycle. Communities nationwide have already responded to the current food, health, and social crisis spurred by COVID-19 by creating mutual aid networks, resource sharing, and employing free to sliding scale pricing. This cooperative crisis response is based on community need and democratic decision making.

COVID-19 has pushed us towards more cooperative structures as businesses work to address the needs of their communities. Those who have lost their jobs are creating new ones for themselves. Successful crowd-funding and the emergence of locally rooted jobs serve to provide reparations to the Black community by meeting demands not met by capitalism. For example, Activation, Venmo @Activation, a Black Trans-led arts residency and cooperative, is crowdfunding to provide a permanent homestead, artist residency, QTBIPOC sanctuary, permaculture farm, and healing space on 15 acres of land has reached $90K out of $750K. The Future Farm Fund, a project by Amber Tamm, a Black farmer, Vemmo @ambertamm, has raised $100K out of $150K for collective land ownership in order to regenerate soil, create safe space, foster community healing, and grow local food. Grassroots organization, Herbal Mutual Aid Network, Venmo @chat_noir, founded by Yves B. Golden and Remy Maelen, provides free plant-based care for Black people seeking support due to the ongoing crisis of racial violence and injustice among many others.

The workshop was a necessary introduction to a conceptual understanding of cooperative economics for many of us, however, the fact that Dr. Gordon Nembhard was not mentioned was a glaring omission. The long history of economic cooperation founded by Black communities, necessitated by anti-Black capitalism, must be credited as a model when contextualizing Cooperative Economics today. The origins of this framework are owed to Black thinkers and theorists such as Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard. “Many of the same leaders who promoted political rights for African Americans and petitioned the government in many different ways, also more quietly and in practice promoted economic cooperation as the way to help Black communities survive racial and economic discrimination: W. E. B. Du Bois, A. Philip Randolph, Marcus Garvey, E. Franklin Frazier, Nannie Helen Burroughs, George Schuyler, Ella Jo Baker, Dorothy Height, Fannie Lou Hamer, and John Lewis, as well as Halena Wilson, Jacob Reddix, W. C. Matney, Charles Prejean, Estelle Witherspoon, Ralph Paige, and Linda Leaks,” includes Nembhard. From pre-Civil War to post- Civil Rights many systemic exclusionary tactics have sidelined the contributions of Black intellects. These individuals form a collective legacy of resource redistribution and community cooperation. They must be cited and honored.

After doing some research, here are five takeaways to turn theory into action for the restaurant industry:

- Start a study group to drive self-study and pool publications and resource share

- Inquire at surrounding Co-ops, CSAs, Barter Clubs, Community Land Trusts, and Credit Unions about sustainable cooperative structures

- Organize with owners and workers in order to shift towards worker-owned structures

- Partner, trade, and gift with local food purveyors, farms, other food businesses

- Contribute to, fund, and support your local organizing efforts i.e. food relief programs, bailout efforts, collective land ownership, cooperative housing, paid political and educational sabbatical etc.