Design has been championing the call for “human-centered design” since the 50’s as an extension of design’s role as a handmaiden to the business of selling things.1 But as we confront the consequences of our consumer culture in the form of global warming and the toxicity of the anthropocene, designers are calling for a shift to a more-than-human design framework that includes the perspectives of living and non-living entities. We believe the future lies in embracing our interdependent, interwoven, interspecies reality. After all, what is being human if not being a loose conglomeration of human cells and microbial collaborators? As we look towards our collective future, the path forward only makes sense when we imagine it together.

- 1. Victor Papanek’s Design for the Real World, 1971.

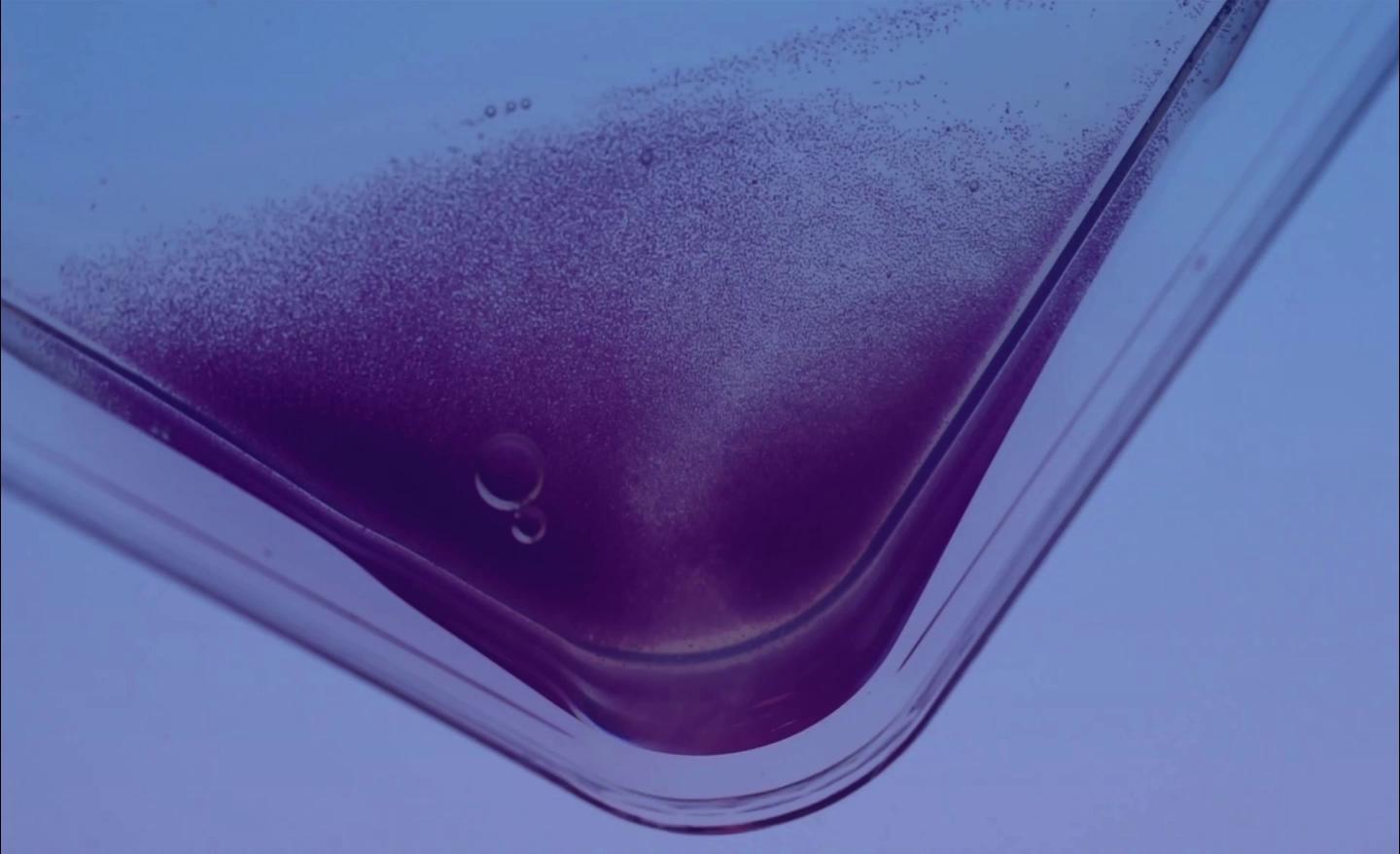

We’ve been fermenting as long as we’ve been storing foods. In our current print issue on Seeds, Dr. Johnny Drain writes about the long relationship between humans and a specific set of flavor-inducing microbes. As he writes, “When we ferment, we build and design systems that center care-giving as a practise.”

How can bug-based pet food curb climate change? What are some of the ways people have been incorporating bugs into their diets? These are just some of the questions that Tansha Vohra explores in her research journal, Boochi. In this particular piece, Tansha explores the relationship between women and insects. Her fascinating research highlights how eating insects has served as social and dietary nutrition for women operating in hunter-gatherer societies.

As a part of our Urban Ecologies series, Avery Hill meditates on what wilderness means what the future of wilderness will look like. Avery investigates the potential that cities might hold to provide sanctuary for species driven from their historic habitats by climate and land-use change.

Somnath Bhatt speaks with Arjun Potter on his research on herbivores in Gongorosa National Park in Mozambique. In this piece for the series Gut Vision, Arjun, whose research centers around using methods such as DNA metabarcoding to break down the diets of grazing animals in great detail, explains how building an understanding of the diets of herbivores can inform the future of our own diets.

The act of sharing has always formed the backbone of Haenyeos are women who maintain the traditional profession of harvesting edible sea creatures from the ocean on Korea’s Jeju Island. In this interview with Faith Kim, a graphic designer who left New York City during the pandemic to return to Korea to be with her family, we talk about her time spent free-diving with the haenyeo community. In this conversation for our series, Methods + Provisions, Faith explains how these women function as stewards of the ocean through their commitment to preserving traditional haenyeo practices. Faith’s reflections on haenyeo rituals and routines paint a portrait of the relationship of interdependency between these women and the ocean.

A community-centered food system requires a reimagination of our current system on every level. Star Route Farm, an organic farm in Upstate New York, has done just that, shifting all of its production toward mutual aid under the belief that everyone ought to have access to fresh, delicious produce. In this piece for our series on Degrowth, MOLD speaks with Star Route’s farmers about the transition into full-time mutual aid production and about farming as an artistic practice.

Early this winter we visited Daughter, a coffee shop in Crown Heights, Brooklyn as it prepared to open its doors. The cafe, which was founded upon community-centered values, has embedded mutual aid into its business model, promising to donate a portion of every quarter’s profits to local organizations. Since the publishing of this piece, Daughter has quickly become a community establishment, hosting food pop-ups, readings, fundraisers and a meal contribution initiative with a local women’s facility, the Anchor House.