In our wellness-world, we know what ingredients make up our granola bars, jean jackets, ice tea and body wash — but what about our walls? The roof over our heads? Where is the nutrition label for vinyl flooring or masonry veneers?

In a world growing more hazardous by the day, what do we consider impactful to the wellbeing of our bodies and selves? There’s a general consciousness around the impact of substances we consume, from the food we eat, the liquids we drink, the clothing we wear and the elixirs we cleanse and beautify our bodies with. All of these make up our “second skin”.However when we expand our understanding of the “self” to our “third skins”, or the environments we live in, the conversation around health and wellbeing shifts from individual choices to environmental, social and economic structures.

Our “third skin” encompasses everything from the air we breathe to the water we shower with. 80% of our time is spent indoors, surrounded by walls that most people have no clue the composition of. Unlike food, the homes we live in seem less within our control. With a tumultuous real estate market growing more precarious by the day, many of us feel fortunate to even have housing, a working sink, a stove, a window or enough space to pace around, let alone worry about what may be in our floors and walls.

Healthy Materials Lab is a design research lab at Parsons School of Design, committed to a design philosophy which centers people’s health in all design decisions. When stories like lead poisoning in Flint, Michigan and fire disasters due to flammable insulation in London at the Grenfell Towers break news, Healthy Materials Lab creates awareness on toxic building materials and their prevalence in our communities.

Apart from raising awareness, Healthy Materials Lab creates resources and supports designers and architects to make healthier places for all people to live. Their goals are to improve common building materials to reduce exposure to toxins and improve health; foster knowledge and awareness of today’s healthier material alternatives by making them more marketable, accessible and popular; empower communities living in poverty to remove toxins in their built environments; educate professionals, teachers and students about the issue of material health and enable them to change current practices; and work with manufacturers to promote transparency while driving innovation.

Earlier this year MOLD sat down with Jonsara Ruth and Allison Mears, Directors and Co-Founders of Healthy Materials Lab, to understand the importance of healthy buildings to personal, communal and environmental wellbeing.

Hiba Zubairi:

In what ways can the material composition of our built environment be bad for our health? What prevalent threats or health risks exist in our building materials and how we interact with them?

Jonsara Ruth:

I’ll just start by saying that we look at materials through every stage of their life cycle. I think an assumption is that we start with the installation phase in our considerations of how people are exposed [to toxins] living with the materials. But we start before that, looking at the impact of the materials from the raw materials origin. So, from where the ingredients were harvested, mined or collected through to the processing and production of those ingredients into building materials. We also look at the transportation and installation of those materials into the people’s homes and living places, and after that, the de-installation and disposal or recycling.

We look at each of those stages through the lens of human and environmental exposure. One example is the trend of vinyl flooring, or luxury vinyl flooring (LVT). Flooring isn’t harmful anymore to people in the in-use phase because it no longer carries the chemical called phthalate. So a lot of manufacturers are touting this “great, new invention” that will no longer expose people to phthalate.

But as we know from the recent train accident in Ohio, which was carrying the ingredients used to make LVT flooring, those materials are harmful outside of the in-use phase. Because of the accident,so many people have been affected. They’re many more examples in the life cycle of even just LVT flooring where we could pinpoint all these places where that particular material is harmful to people’s health, and contributes to degrading cultures.

Alison Mears:

[Through Healthy Materials Lab] we really focus on the interrelatedness of the decisions that we make as architects and designers. We can be part of a system that is complicit in building with materials that have a toxic content, or we can actually make a change where we create better systems by specifying better products. The relationship between what we do and the bigger ecosystem is really important. Sometimes we think of ourselves, as architects and designers, having very little power, in the scale and magnitude of the changes we are confronted with. But single decisions that we make can sometimes have a really profound impact. And so when you ask that question, ‘What ways are buildings bad for our health?’ They’re bad for our health because we’re making bad decisions but they can also be really good for our health. They can be good for our families, for the contractors that are installing, for the shipping and handling staff, for the manufacturers that create those materials, for the industry, for your neighbors and community members who live and work across the road from the manufacturing facility where they can live in healthy and safe environments. It’s important to have an ecosystem-based approach.

JR:

There are good examples too. If you live near a field of flax for example, then the soil is getting better across the street and the air that you breathe is getting better as well. If you live in a home that’s built of HempLime, the air inside is naturally modulating the humidity so everything about it becomes healthier. Production-wise, if you’re in a job where you are producing building materials out of HempLime, the ingredients you’re exposed to every day are naturally antimicrobial, so they’re naturally better for you. You are not exposed to vinyl chloride, or all these other crazy chemicals. The whole system gets better, as a result.

HZ:

I hear that and I think, “Why do we not live like that?” Why is there this norm of using such chemically enriched materials? Is it because of how we’ve set up our supply chains or is it, you know, some part due to ignorance?

AM:

I think it’s a market force in the U.S. market. Forces are incredibly strong and they create these financial economic systems that make a lot of decisions for us. Why are so many synthetic toxic chemicals used in building products? We could say for a number of different reasons, there’s a financial incentive to make and sell chemicals. Using synthetic chemicals benefits the chemical industry, which is the third largest industry in the U.S. The government is highly motivated to keep its profits strong so it can continue to make money on the backs of the fossil fuel industry. Basically, those two industries are interrelated.

JR:

That is a really good point that Alison’s making, that is, it is an economic issue. The fossil fuel industry pulls a natural ingredient out of the land, petroleum—which is ancient plants that are degraded into this oil—but in order to make it usable for all the ways that we use the fuel, they need to distill and process it. There’s all of this waste from the reaction. The idea is to use the waste and put it in other stuff. It’s free for them to make it but they charge money and make a margin by putting it in flooring and all these building products we know. Then they can rally around these lobbyists and have all these other ways to make it really hard to move away from these practices.

Design is portion, position, phenomenology, light, air and space. We have to understand that as designers, we create people’s environments and experiences. It’s not just materials.

AM:

In other places in the world, they have governments that actually look to protect the people who live in that country so they have policies and regulations that protect those people but in the U.S., there’s a real absence of regulation. There were and there have been some policies that have attempted to regulate the petrochemical industry. But of the 86,000 chemicals currently in use, only five of them are partially banned.

That is because of lobbying in the US where these companies are as powerful or more powerful than the US government because of their resources. These chemicals are not required to be tested for their human health impacts. So people don’t typically understand that. They imagine that anything that comes into the marketplace, there is some kind of regulation or testing done so that we know that it’s not harmful to us, but that isn’t the case with these chemicals.

Some might ask, ‘Why do we not know about this?’ ‘Why isn’t it part of the education of an architect or designer?’.

And part of that is the tactics that the chemical industry uses, they understand the dangers of the chemicals, but want to suppress that research and not have that part of the discourse around the use of chemicals and products. They actively negate any of that research by others as well. They’re incredibly litigious in terms of their actions, to protect the industry.

JR:

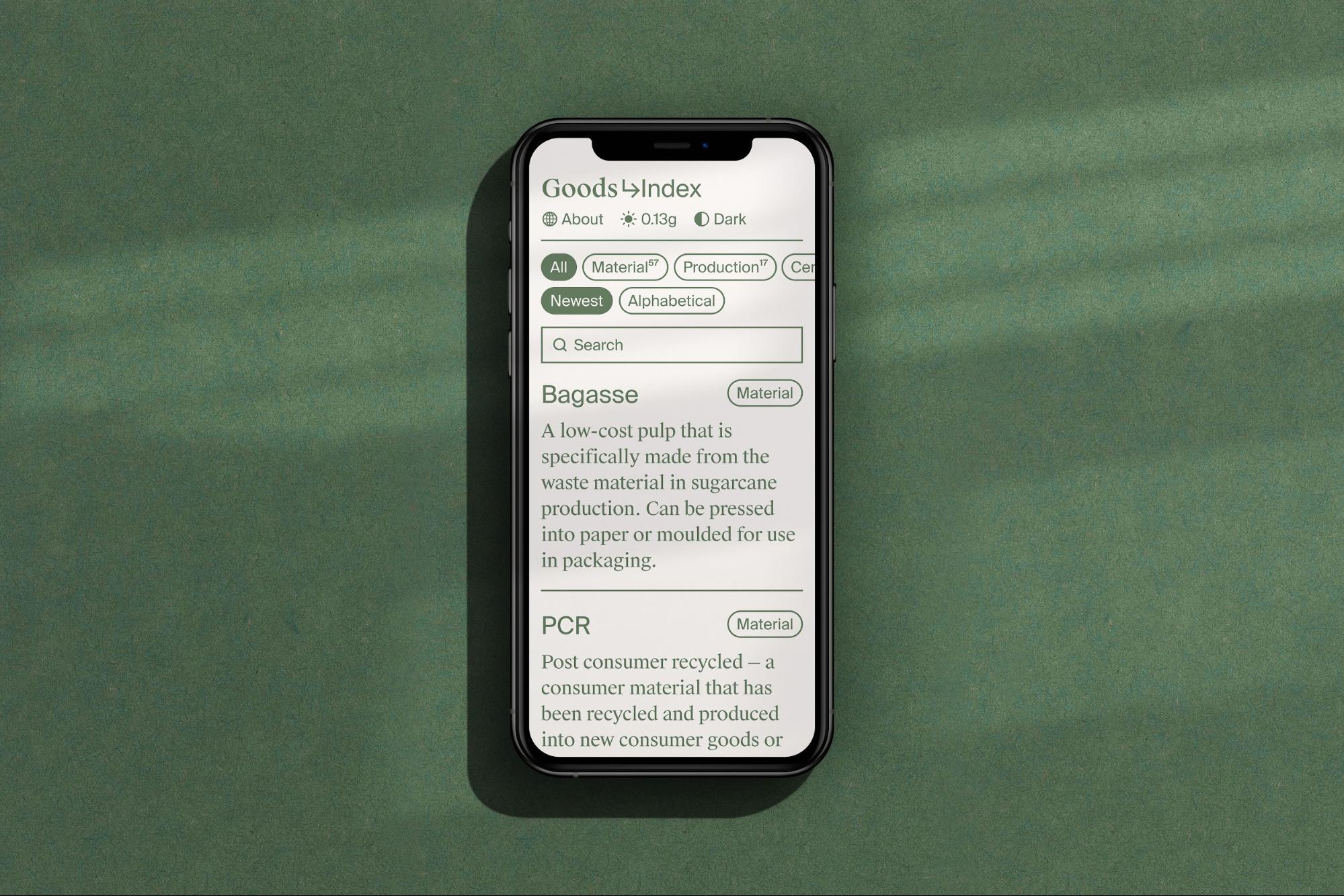

With regards to MOLD, the thing that we found to be intriguing was the relationship between food and building materials.

There’s a lot of aspects of building material manufacturing that are also applicable to the fast food movement or food production industry. Things are super processed, there are tons of preservatives put in them and synthetic colors added so that it looks appealing or so that it stays on a shelf for longer.

AM:

Most factory-produced food has an ingredients list, whereas building products don’t necessarily have that. When you look at the ingredients label you see what’s in it. And you can make a choice based on that knowledge.

JR:

And with building products, there isn’t an ingredient label. Although, in the last few years there have been voluntary “ingredient labels” introduced by a small percentage of building manufacturers.

There’s the Health Product Declaration and Environmental Product declarations, which mandate that manufacturers report ingredients and statistics about their building materials for transparency.

JR:

But it’s not perfect because they only need to declare the things they want to declare on those labels. So they might declare 50% or 60% or 70%, or maybe they’re really progressive and want to declare 90% of the ingredients content of their product, but they can retain that other percentage because it has some intellectual property value, and it can be that last 10% or 20 or 25% is all the toxic ingredients that are in the product that they don’t want to share with us.

It’s a better system, but it’s still incredibly flawed.

HZ:

If you look to the past, as in pre-industrialization, walls would have one or two materials, at most. When large-scale housing development emerged as a building strategy that all began to change. I’m wondering how that change has resulted in our current context and how it impacts our building materials. How does our current socio-political context impact how we interact with our built environment in terms of its materials composition?

JR:

Because climate change is felt by everybody, what [you] hear about now is carbon. There’s a lot of attention being paid to how we can stop using concrete, steel and glass and yet, it doesn’t stop people from building with all of these materials.

From a grassroots perspective, the safest, healthiest and most responsible way to build buildings is not to build new buildings, but to restore old buildings. So one way to build healthier, is to look at the burgeoning materials that can be used to remediate [existing structures].

We want to redirect efforts to build with things that are actually going to, if not eliminate, at least balance out the toxins that are present. So thinking about how you build, how you insulate or re-insulate with healthier insulations, or how you coat the surfaces of a space so that it’s healthier. These systems can be used to design the renovation and restoration of buildings. It doesn’t eliminate the toxicity but it’s a path forward to making healthier spaces for people to live in.

AM:

The reason why there are [now] so many different components in a wall system is because of economic forces. We used to build with massive components that had substance, but newer, lighter-weight materials allow for easier installation. That means you reduce the labor component, the amount of time it took to construct buildings and the level of expertise in construction – you’re able to rapidly construct buildings. At the time, there was a drive to build at rapid rates for less cost. It was a driver in the creation of the 20th-century city and the suburbs.

With HempLime we were trying to re-envision building materials by seeing if we could get down to two or three different building materials in construction. Not only are we simplifying but we’re using better products within that system. We have this benefit of simplification and health as part of that equation.

Part of the education of an architectural designer is that there is an open palette, you can do whatever you want and be creative in terms of the materials you use. But by having a limitless palate we are in some ways creating waste through creating profit for others, rather than really producing beautiful places for us to live in.

JR:

This consumption mentality proliferates the market because the market follows our consumption.We, as clients, want them to have a plethora of colors and finishes in flooring but that creates a lot of waste for our planet, pollution of our soil, water systems and landscape. It leads to the degradation of people’s living conditions. By reducing that palette, design is no longer just a curatorial choice. You force people to do real design because design is not just choosing something.

Design is portion, position, phenomenology, light, air and space. We have to understand that as designers, we create people’s environments and experiences. It’s not just materials.

HZ:

I think that was definitely a big part of my education [as an architect] as well. We were never made to think about where these materials came from. What does it cost to get those materials on to our site and to use it in the exuberant way that we are using it?

JR:

We need to teach our students about the holistic implications of their material choices. Five billion tons of LVT arrive in North America every year because people consume it and it comes in all these different wood styles. There’s so much demand that it used to be produced in the United States but we can’t fulfill the demand anymore. So now they’ve set up LVT factories in the northern regions of China where labor legislation and regulation is non-existent. They go into small towns of indigenous Uyghur communities and take people out of the community forcefully, send them into training, put them in these factories, destroying families and communities. And when they start working in the factory they’re exposed to all these chemicals which lead to diseases.

We need to ask as designers, are you sure you want to contribute to this? Those are the kind of choices we’re making when we choose a material.

HZ:

Everything you guys are talking about frames something really important. Sustainability goes hand in hand with human rights. We are living things and what happens to our bodies is a direct reflection of what’s happening to our world. Disregarding one undermines your efforts to mitigate the other. The way that we value other people’s lives is a reflection of how we value our own bodies and our own lives as well as other living things on our earth. Sustainability, human rights and healthy living are all linked because you can’t silo these issues. In art or food, we can choose not to eat a meal or not to go see a painting, but you can’t choose not to live in or go to school in a certain building. I find this often leads to a very benign relationship with our built environment.

Low-income and often marginalized communities are the ones affected the most by harmful chemicals in building materials. A big part of that is because they have less agency over where they can live, where they can go to school. The example that comes to mind is the Grenfell towers in London that caught fire due to accelerants in their insulation. This building practice is prevalent in London’s low-income project housing. We can look at high concentrations of lead in low-income housing across the United States. Why are low-income communities the ones that are affected most by harmful chemicals?

AM:

We’re gonna talk about it from the U.S. perspective. Because there is no right to housing in the U.S., housing is considered a privilege. If the government decides to build public or affordable housing, the amount of money that they allocate to that construction is very low because it’s not considered to be something that is an important initiative of the city, state government, or federal government.

You’re lucky to have housing if you’re poor, you know? And so long as it’s something that has four walls and a door, then you should be grateful for what you have. That’s the philosophy here and it means there’s no money for construction, the materials that are used to construct that housing, it’s the lowest cost products you possibly can find in the marketplace. And those have got to be the most toxic, you know?

It’s the really higher VOC paints, it’s the vinyl products, it’s the lack of insulation. It’s really bad. Poor quality doors, terrible kind of vinyl cheap windows that don’t really work very well. And it is in the worst possible places in the city, where the land has the least value. And that’s usually because it’s close to industry factories and waste brownfields. There’s a history and perpetuation of this system so that low-income families are living in these highly toxic environments for generations. We carry this into generational trauma on our bodies, that is inherited and that perpetuates a whole range of human diseases that give us a disadvantage in every aspect, from unaffordable medical care to an inability to work. It’s intergenerational trauma through exposure which then hinders the ability to chart a new path.

JR:

For example, one of the most prevalent toxins in plastics is Obesogen, which when exposed to long term makes individuals gain weight and billow out. There’s a misconception that obesity is because of lack of exercise or poor nutrition. But, in the U.S. it is actually a lot about exposure to plastics and synthetics. And so then if somebody has gained all this weight, which then hinders their cognition, hinders their physical activity, then they’re even more inhibited to help themselves with their situation.

AM:

It’s endemic racism, perpetuated generation to generation and in a way that isn’t as obvious as redlining from the ’20s and ’30s in U.S. cities. Now we have really badly built housing, a lack of access to health services and a lack of awareness and education around health. It’s a systemic problem. And building a house is a piece as a component of this ultimately racist system.

HZ:

Working within the architecture and design industry, what work has Healthy Materials Lab seen or taken part in that makes you hopeful for the future?.

AM:

We’re working with a group in northern Minnesota, designing housing for older women within the Lower Sioux Indian community, who currently live in these terrible open housing developments. It’s a federal government housing scheme that was built in the ‘60s.

We’re looking at working with them to design simple, light-filled, healthier buildings made from locally-grown hemp mixed with lime as the wall composition and local timber as the rain screen. This is a prototype for housing with a particular group in northern Minnesota and that potential to have even one or two families living in healthier housing is the motivation for us. There’s a lot of potential with developing new systems, new ways of doing things that are locally based, for local economies, with local labor, local initiatives, local politics, local everything. You know the right to self-determination and healthy living combined could be wonderful. And it’s possible!

We’re envisioning a future where members of this community will be a part of a new industry of building healthier homes out of plants that they grow. The whole system can be vertically integrated and locally based. Because they’re so hands on with the process, they’ll become the experts for the rest of the country—they’re starting to form cooperatives. So the system becomes a collective cooperative model of production, which is the opposite of the models we see currently in construction products.

JR:

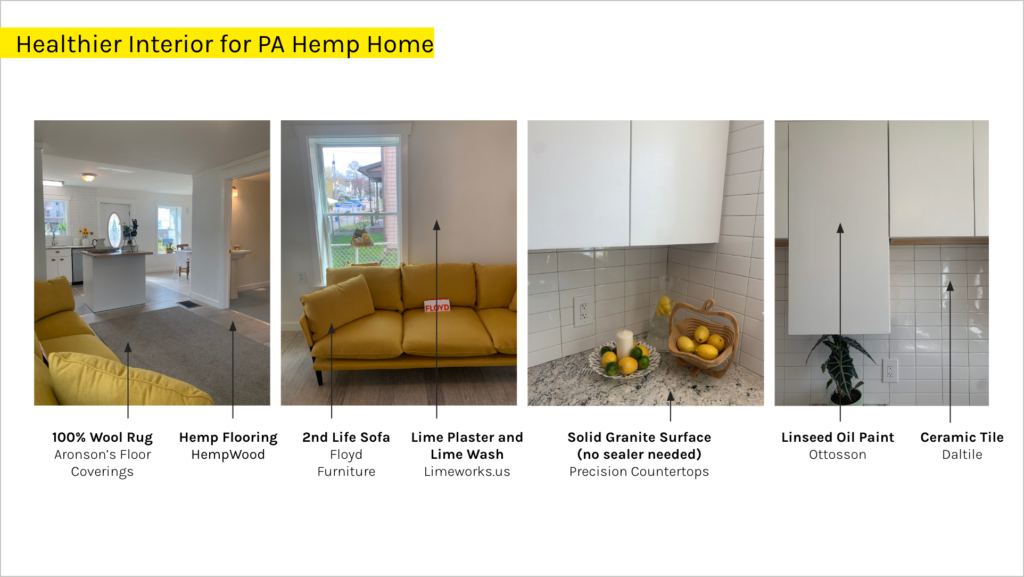

We did another pilot project with a community group in northwestern Pennsylvania who provides housing to a lot of low-income families, especially low-income people who have disabilities. Their main mission is to allow people with disabilities to live independently.

They started by retrofitting homes before realizing that it was more expensive than just building new homes. So then they started building new homes but ran out of vinyl and bad materials so they started exploring hemp and lime as building materials around the same time as us. So we combined forces and joined a collaborative where we made a pilot home which was just unveiled. It was a small, humble wood frame home that was retrofitted with HempLime insulation and then outfitted with all healthy materials. This community organization is called Don Services and they have their own in-house construction team, who had to overcome a big learning curve very quickly in order to use the materials. And they learned it in a few days. They went through trials and mistakes but they were able to do it and now they’re very empowered to do it again. And so, those are really promising examples of how this whole thing can change. It also made us consider how the next materials economy might re-ignite agriculture with a focus on taking care of the soil, water systems and land through the plants that we plant, through the seeds cultivated. Instead of using materials that necessitate workers to work in factories filled with heavy chemicals, they might be able to work in fresh air, growing something like hemp.

AM:

They don’t have to use pesticides and insecticides that gave them cancer previously, because you don’t need that with a crop like hemp, which is very sturdy. So, farming is better in a number of different ways.

HZ:

It really gives agency to every individual because their building is being made in a way that directly relates to them. Those farmers are their neighbors, they can visit the field that their house was made of and I think that gives you a different relationship to the materials surrounding you. We can rethink building technology as this exchange of knowledge rather than a means to commodify a product.

I want to finish off on one question: What does a healthy building look like?

AM:

It could look like whatever you wanted it to look like, I think. But it does require us to think differently about the way we build. It requires invention and innovation in terms of the wall systems. The appropriation of ancient technologies reinterpreted into new technologies means we have to do the work that we always had to do as architects and designers. It’s about asking different questions though. How do things come together in a way that is beneficial? In a way that creates these new beautiful healthy environments for people?

Think about designing for 100 year lives and think of reuse at the end of the hundred years.